Abstract

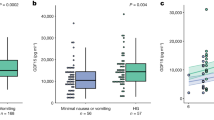

Prenatal stress can lead to long-term adverse effects that increase the risk of anxiety and other emotional disorders in offspring. The in utero underpinnings contributing to such phenotypes remain unknown. We profiled the transcriptome of placental specimens from women who lived through Hurricane Sandy during pregnancy compared to those pregnant during non-Sandy conditions. Following birth, longitudinal assessments were conducted in their offspring during childhood (~3–4 years old) to measure steroid hormones (in hair) and behavioral and emotional problems. This revealed a significant link between prenatal Sandy stress (PNSS) and child HPA dysfunction, evident by altered cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and cortisol:DHEA levels. In addition, PNSS was associated with significantly increased anxiety and aggression. These findings coincided with significant reorganization of the placental transcriptome via vascular, immune, and endocrine gene pathways. Interestingly, many of the most prominently altered genes were known to be uniquely expressed in syncytiotrophoblast (STB)-subtype of placental cells and harbored glucocorticoid response elements in promoter regions. Finally, several vascular development- and immune-related placental gene sets were found to mediate the relationship between PNSS and childhood phenotypes. Overall, these findings suggest that natural disaster-related stress during pregnancy reprograms the placental molecular signature, potentially driving long-lasting changes in stress regulation and emotional health. Further examination of placental mechanisms may elucidate the environment’s contribution to subsequent risk for anxiety disorders later in life.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The RNA-sequencing datasets generated and analyzed in the current study were submitted to the NCBI Sequencing Read Archive with accession code: PRJNA719417.

References

Graignic-Philippe R, Dayan J, Chokron S, Jacquet AY, Tordjman S. Effects of prenatal stress on fetal and child development: a critical literature review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;43:137–62.

Li H, Bowen A, Bowen R, Balbuena L, Feng C, Bally J, et al. Mood instability during pregnancy and postpartum: a systematic review. Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2020;23:29–41.

Dunkel Schetter C. Psychological science on pregnancy: stress processes, biopsychosocial models, and emerging research issues. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62:531–58.

Kim DR, Bale TL, Epperson CN. Prenatal programming of mental illness: current understanding of relationship and mechanisms. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17:5.

Van den Bergh BRH, van den Heuvel MI, Lahti M, Braeken M, de Rooij SR, Entringer S, et al. Prenatal developmental origins of behavior and mental health: The influence of maternal stress in pregnancy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;117:26–64.

Coussons-Read ME. Effects of prenatal stress on pregnancy and human development: mechanisms and pathways. Obstet Med. 2013;6:52–7.

McLean MA, Cobham VE, Simcock G, Elgbeili G, Kildea S, King S. The role of prenatal maternal stress in the development of childhood anxiety symptomatology: the QF2011 Queensland Flood Study. Dev Psychopathol. 2018;30:995–1007.

Yong Ping E, Laplante DP, Elgbeili G, Jones SL, Brunet A, King S. Disaster-related prenatal maternal stress predicts HPA reactivity and psychopathology in adolescent offspring: project Ice Storm. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020;117:104697.

Nomura Y, Davey K, Pehme PM, Finik J, Glover V, Zhang W, et al. Influence of in utero exposure to maternal depression and natural disaster-related stress on infant temperament at 6 months: The children of Superstorm Sandy. Infant Ment Health J. 2019;40:204–16.

Kratimenos P, Penn AA. Placental programming of neuropsychiatric disease. Pediatr Res. 2019;86:157–64.

Bronson SL, Bale TL. The placenta as a mediator of stress effects on neurodevelopmental reprogramming. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:207–18.

St-Pierre J, Laplante DP, Elgbeili G, Dawson PA, Kildea S, King S, et al. Natural disaster-related prenatal maternal stress is associated with alterations in placental glucocorticoid system: the QF2011 Queensland Flood Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;94:38–48.

Zhang W, Li Q, Deyssenroth M, Lambertini L, Finik J, Ham J, et al. Timing of prenatal exposure to trauma and altered placental expressions of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis genes and genes driving neurodevelopment. J Neuroendocrinol. 2018;30:e12581.

Zhang W, Ham J, Li Q, Deyssenroth MA, Lambertini L, Huang Y, et al. Moderate prenatal stress may buffer the impact of Superstorm Sandy on placental genes: stress in pregnancy (SIP) study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0226605.

Finik J, Nomura Y. Cohort profile: stress in pregnancy (SIP) study. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:1388–k.

Manenschijn L, Koper JW, Lamberts SW, van Rossum EF. Evaluation of a method to measure long term cortisol levels. Steroids. 2011;76:1032–6.

Sauve B, Koren G, Walsh G, Tokmakejian S, Van Uum SH. Measurement of cortisol in human hair as a biomarker of systemic exposure. Clin Invest Med. 2007;30:E183–91.

Stalder T, Kirschbaum C. Analysis of cortisol in hair–state of the art and future directions. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:1019–29.

Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. BASC-2: Behavior Assessment System for Children. 2nd ed. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 2004.

Bradstreet LE, Juechter JI, Kamphaus RW, Kerns CM, Robins DL. Using the BASC-2 parent rating scales to screen for autism spectrum disorder in toddlers and preschool-aged children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2017;45:359–70.

Norris F, Kaniasty K, Scheer D. Use of mental health services among victims of crime: frequency, correlates, and subsequent recovery. J Consulting Clin Psychol. 1990;58:538–47.

Spielberger CD. State-trait anxiety inventory: bibliography. 2nd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1989.

Murray DCJ. Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh Depression Scale (EPDS). J Reprod Infant Psychol. 1990;8:99–107.

Andrews S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. 2010.

Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21.

Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550.

Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, Fernandez NF, Duan Q, Wang Z, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W90–7.

Pique-Regi R, Romero R, Tarca AL, Sendler ED, Xu Y, Garcia-Flores V, et al. Single cell transcriptional signatures of the human placenta in term and preterm parturition. Elife. 2019;8:e52004.

Togher KL, Togher KL, O’Keeffe MM, O’Keeffe MM, Khashan AS, Khashan AS, et al. Epigenetic regulation of the placental HSD11B2 barrier and its role as a critical regulator of fetal development. Epigenetics. 2014;9:816–22.

Zhu Q, Pan P, Chen X, Wang Y, Zhang S, Mo J, et al. Human placental 3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/steroid Delta5,4-isomerase 1: identity, regulation and environmental inhibitors. Toxicology. 2019;425:152253.

Liao S, Vickers MH, Stanley JL, Baker PN, Perry JK. Human placental growth hormone variant in pathological pregnancies. Endocrinology. 2018;159:2186–98.

Gude NM, Roberts CT, Kalionis B, King RG. Growth and function of the normal human placenta. Thromb Res. 2004;114:397–407.

Delorme-Axford E, Donker RB, Mouillet JF, Chu T, Bayer A, Ouyang Y, et al. Human placental trophoblasts confer viral resistance to recipient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:12048–53.

Robbins JR, Skrzypczynska KM, Zeldovich VB, Kapidzic M, Bakardjiev AI. Placental syncytiotrophoblast constitutes a major barrier to vertical transmission of Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000732.

Ander SE, Diamond MS, Coyne CB. Immune responses at the maternal-fetal interface. Sci Immunol. 2019;4:eaat6114.

Huppertz B. The anatomy of the normal placenta. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:1296–302.

Capron LE, Ramchandani PG, Glover V. Maternal prenatal stress and placental gene expression of NR3C1 and HSD11B2: The effects of maternal ethnicity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;87:166–72.

Hompes T, Izzi B, Gellens E, Morreels M, Fieuws S, Pexsters A, et al. Investigating the influence of maternal cortisol and emotional state during pregnancy on the DNA methylation status of the glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) promoter region in cord blood. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:880–91.

Oberlander TF, Weinberg J, Papsdorf M, Grunau R, Misri S, Devlin AM. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics. 2008;3:97–106.

Kamin HS, Kertes DA. Cortisol and DHEA in development and psychopathology. Horm Behav. 2017;89:69–85.

Grillon C, Pine DS, Baas JM, Lawley M, Ellis V, Charney DS. Cortisol and DHEA-S are associated with startle potentiation during aversive conditioning in humans. Psychopharmacology. 2006;186:434–41.

Fava M, Rosenbaum JF, MacLaughlin RA, Tesar GE, Pollack MH, Cohen LS, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate/cortisol ratio in panic disorder. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:345–50.

Seckl JR, Meaney MJ. Glucocorticoid programming. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1032:63–84.

Weinstock M. The potential influence of maternal stress hormones on development and mental health of the offspring. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:296–308.

Thayer ZM, Wilson MA, Kim AW, Jaeggi AV. Impact of prenatal stress on offspring glucocorticoid levels: a phylogenetic meta-analysis across 14 vertebrate species. Sci Rep. 2018;8:4942.

Send TS, Bardtke S, Gilles M, Wolf IAC, Sutterlin MW, Wudy SA, et al. Prenatal maternal stress is associated with lower cortisol and cortisone levels in the first morning urine of 45-month-old children. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;103:219–24.

Redman CW, Staff AC. Preeclampsia, biomarkers, syncytiotrophoblast stress, and placental capacity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:S9 e1.

Han C, Han L, Huang P, Chen Y, Wang Y, Xue F. Syncytiotrophoblast-derived extracellular vesicles in pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1236.

Ishihara N, Matsuo H, Murakoshi H, Laoag-Fernandez JB, Samoto T, Maruo T. Increased apoptosis in the syncytiotrophoblast in human term placentas complicated by either preeclampsia or intrauterine growth retardation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:158–66.

O’Donnell KJ, Bugge Jensen A, Freeman L, Khalife N, O’Connor TG, Glover V. Maternal prenatal anxiety and downregulation of placental 11beta-HSD2. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:818–26.

Seth S, Lewis AJ, Saffery R, Lappas M, Galbally M. Maternal prenatal mental health and placental 11beta-HSD2 gene expression: initial findings from the mercy pregnancy and emotional wellbeing study. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:27482–96.

Hobel CJ, Dunkel-Schetter C, Roesch SC, Castro LC, Arora CP. Maternal plasma corticotropin-releasing hormone associated with stress at 20 weeks’ gestation in pregnancies ending in preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:S257–63.

Sandman CA. Prenatal CRH: an integrating signal of fetal distress. Dev Psychopathol. 2018;30:941–52.

Robinson BG, Emanuel RL, Frim DM, Majzoub JA. Glucocorticoid stimulates expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone gene in human placenta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5244–8.

Conradt E, Lester BM, Appleton AA, Armstrong DA, Marsit CJ. The roles of DNA methylation of NR3C1 and 11beta-HSD2 and exposure to maternal mood disorder in utero on newborn neurobehavior. Epigenetics. 2013;8:1321–9.

Jensen Pena C, Monk C, Champagne FA. Epigenetic effects of prenatal stress on 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-2 in the placenta and fetal brain. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39791.

Nugent BM, O’Donnell CM, Epperson CN, Bale TL. Placental H3K27me3 establishes female resilience to prenatal insults. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2555.

Braithwaite EC, Kundakovic M, Ramchandani PG, Murphy SE, Champagne FA. Maternal prenatal depressive symptoms predict infant NR3C1 1F and BDNF IV DNA methylation. Epigenetics. 2015;10:408–17.

Mulligan CJ, D’Errico NC, Stees J, Hughes DA. Methylation changes at NR3C1 in newborns associate with maternal prenatal stress exposure and newborn birth weight. Epigenetics. 2012;7:853–7.

Spann MN, Monk C, Scheinost D, Peterson BS. Maternal immune activation during the third trimester is associated with neonatal functional connectivity of the salience network and fetal to toddler behavior. J Neurosci. 2018;38:2877–86.

Hsiao EY, Patterson PH. Activation of the maternal immune system induces endocrine changes in the placenta via IL-6. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:604–15.

Bronson SL, Bale TL. Prenatal stress-induced increases in placental inflammation and offspring hyperactivity are male-specific and ameliorated by maternal antiinflammatory treatment. Endocrinology. 2014;155:2635–46.

Alaiti MA, Orasanu G, Tugal D, Lu Y, Jain MK. Kruppel-like factors and vascular inflammation: implications for atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2012;14:438–49.

Jakubowski M, Szahidewicz-Krupska E, Doroszko A. The human carbonic anhydrase II in platelets: an underestimated field of its activity. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:4548353.

Sutherland S, Brunwasser SM. Sex differences in vulnerability to prenatal stress: a review of the recent literature. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20:102.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the mothers and their children who have participated in this project. This work was supported by grants MH102729 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to YN and DA030359 from the National Institutes of Drug Abuse (NIDA) to YLH, along with ES029212 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and HD067611 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) to JC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nomura, Y., Rompala, G., Pritchett, L. et al. Natural disaster stress during pregnancy is linked to reprogramming of the placenta transcriptome in relation to anxiety and stress hormones in young offspring. Mol Psychiatry 26, 6520–6530 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01123-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01123-z

This article is cited by

-

Placental transcriptomic signatures of prenatal and preconceptional maternal stress

Molecular Psychiatry (2024)

-

Genome-wide neonatal epigenetic changes associated with maternal exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic

BMC Medical Genomics (2023)

-

Identification and prediction model of placenta-brain axis genes associated with neurodevelopmental delay in moderate and late preterm children

BMC Medicine (2023)

-

Natural Disaster Epidemiology and Reproductive Health

Current Epidemiology Reports (2023)