Abstract

Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (AMNs), characterized by expansile or “pushing” growth of neoplastic epithelium through the appendix wall, are sometimes accompanied by peritoneal involvement, the extent and grade of which largely determine clinical presentation and long-term outcomes. However, the prognosis of tumors entirely confined to the appendix is still debated and confusion remains regarding their biologic behavior and, consequently, their clinical management and even diagnostic nomenclature. We evaluated AMNs limited to the appendix from 337 patients (median age: 58 years, interquartile range (IQR): 47–67), 194 (57.6%) of whom were women and 143 (42.4%) men. The most common clinical indication for surgery was mass or mucocele, in 163 (48.4%) cases. Most cases (N = 322, 95.5%) comprised low-grade epithelium, but there were also 15 (4.5%) cases with high-grade dysplasia. Lymph nodes had been harvested in 102 (30.3%) cases with a median 6.5 lymph nodes (IQR: 2–14) per specimen for a total of 910 lymph nodes examined, all of which were negative for metastatic disease. Histologic slide review in 279 cases revealed 77 (27.6%) tumors extending to the mucosa, 101 (36.2%) to submucosa, 33 (11.8%) to muscularis propria, and 68 (24.4%) to subserosal tissues. In multivariate analysis, deeper tumor extension was associated with older age (p = 0.032; odds ratio (OR): 1.02, 95% confidence intervals (CI): 1.00–1.03), indication of mass/mucocele (p < 0.001; OR: 2.09, CI: 1.41–3.11), and wider appendiceal diameter, grossly (p < 0.001; OR: 1.61, CI: 1.28–2.02). Importantly, among 194 cases with at least 6 months of follow-up (median: 56.1 months, IQR: 24.4–98.5), including 9 high-grade, there was no disease recurrence/progression, peritoneal involvement (pseudomyxoma peritonei), or disease-specific mortality. These data reinforce the conclusion that AMNs confined to the appendix are characterized by benign biologic behavior and excellent clinical prognosis and accordingly suggest that revisions to their nomenclature and staging would be appropriate, including reverting to the diagnostic term mucinous adenoma in order to accurately describe a subset of them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (AMNs) are comparatively uncommon tumors histologically defined by dysplastic mucinous epithelium extending through the wall of the appendix, but lacking infiltrative growth or destructive invasion1,2,3. The biological behavior and clinical course of these neoplasms is heterogeneous and mostly depends on the extent (i.e., stage) of tumor involvement, especially at disease presentation4. For example, most patients with tumors confined to the appendix appear to have a low risk of recurrence after appendectomy5,6. In contrast, patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP), a clinicopathologic condition characterized by intraperitoneal mucinous implants and increasing accumulation of mucinous ascites, exhibit a progressive, often incurable disease course with high risk of recurrence and even mortality5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17.

The discordance between the absence of aggressive histologic features in this neoplasm and its sometimes malignant, albeit low-grade, clinical behavior has resulted in a bewildering collection of confusing and often contradictory terminologies, nomenclatures, and classifications employed to define both the primary appendiceal neoplasm and the resulting peritoneal disease component. While the introduction of the term low-grade AMN (LAMN) initially alleviated some of the confusion stemming from these seemingly contradictory characteristics by using similar terminology to describe both appendiceal and peritoneal disease, slow acceptance and inconsistent usage has resulted in the persistence of disputing opinions5,6,9,11,18,19. In a recent attempt at consensus, the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) defined AMNs as mucinous neoplasms without infiltrative invasion, but classically characterized by certain features, including loss of the muscularis mucosae, submucosal fibrosis, “pushing” or diverticulum-like growth or acellular mucin dissecting into the wall, undulating or flattened epithelial growth, rupture of the appendix, and presence of mucin and/or neoplastic cells outside the appendix1. The use of the term “mucinous cystadenoma” to describe these lesions was not recommended.

Following this consensus document, the most recent edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) tumor classification catalog discourages terms such as “borderline” and “uncertain malignant potential”, and has removed the diagnostic term “mucinous cystadenoma” from its entry on AMNs3. Similarly, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual, in an attempt to address the confusion regarding pathologic reporting, established a single stage for LAMNs confined by muscularis propria termed pTis(LAMN) and belonging to overall prognostic Stage Group 020. However, the same neoplasms are staged as pT3 when neoplastic mucinous epithelium or acellular mucin extend to the subserosa or mesoappendix and belong to prognostic group IIA. Tumor stages pT1 and pT2 are conspicuously absent from the classification of LAMNs. Furthermore, AMNs with high-grade histology (i.e., HAMNs) are distinctly classified according to the staging system for infiltrating carcinomas: pT1 and pT2 categories exist for these tumors, allowing a decision on tumor grade to drive stage considerations.

These staging guidelines and prognostication groupings for tumors entirely confined to the appendix, together with terms such as “uncertain malignant potential” as have been used in the past, would suggest that there is a risk, however small, of recurrence, progression or peritoneal dissemination (i.e., PMP) in these patients. Nevertheless, the exact clinical behavior and appropriate nomenclature for these neoplasms are still a matter of debate and they stand to benefit from additional prognostic data. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the clinicopathologic characteristics and long-term outcomes in a large, single-institution cohort of patients with AMNs histologically confirmed to be entirely confined to the appendix.

Materials and methods

Study cases and inclusion/exclusion criteria

AMNs were retrieved through a keyword search of our surgical pathology records over 22 years (January 2000 to December 2021). Inclusion criteria consisted of unique patients diagnosed with primary mucinous neoplasms limited to the appendix. Cases with the following were excluded: exclusively non-dysplastic epithelial hyperplasia; extra-appendiceal involvement (including of appendiceal serosa and/or peritoneum) by acellular mucin or neoplastic epithelium at presentation (i.e., stages pT4a or pM1); appendiceal adenocarcinomas (with infiltrative, destructive growth); goblet cell adenocarcinomas; neuroendocrine and mixed neoplasms; mucinous neoplasms of the colon or small intestine and patients with ovarian or other peritoneal neoplasms; specimens from endoscopic procedures only (i.e., biopsies); cases where the appendix had not been entirely submitted (sectioned) for histologic examination. Consultations from referring institutions were included only when the appendix had been entirely submitted and all microscopic slides were available for review. Some cases (N = 64) had been previously reported by us4, including 13 with tumor extension in the mucosa, 19 in the submucosa, 8 in the muscularis propria and 24 in the subserosa. They are included here in terms of evaluating the exact depth of tumor extension, reporting appendix dimensions, and providing longer clinical follow-up.

Clinicopathologic data and patient outcomes

Data on demographic and clinicopathologic parameters, including patient age and sex, clinical indication for and type of surgical procedure (simple appendectomy with/without cecectomy vs. extensive ileocolic resection, right hemicolectomy, or total colectomy), presence of perforation or appendiceal diverticulae, gross measurements (length and diameter) of the appendix, histologic status of the resection margin, concurrent diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), tumor grade, number of lymph nodes harvested, if applicable, treatment (hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), cytoreductive surgery, and/or systemic chemotherapy), and patient outcomes (disease recurrence and disease-specific mortality) were obtained by reviewing surgical pathology slides and reports and patient medical records. Appendiceal volume (πr2l), where r is radius (diameter/2) and l is length (both expressed in cm and determined by measurements on gross specimens), was calculated in cubic centimeters. Disease recurrence was defined as evidence of intraperitoneal or other metastatic disease after index surgical resection, established by imaging and/or histopathologic examination. Follow-up was defined as the time from initial diagnosis to event (disease recurrence or disease-specific mortality) or last clinical encounter and was recorded in months. Only patients with at least 6 months of follow-up were included in outcome analysis.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables (patient age and follow-up time, appendix length, diameter, and calculated volume, and number of lymph nodes harvested) were not normally distributed (by Shapiro–Wilk test) and are thus presented as median values with interquartile ranges (IQR; 25th–75th percentile) and were compared using Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis tests, as appropriate. Categorical variables, including patient sex, indication for and type of surgical procedure, concurrent IBD prevalence, presence of appendiceal perforation and diverticulae, neoplasm grade, status of resection margin, and treatment modalities were compared using Pearson chi-squared or one-sided Fisher’s exact tests (the latter if ≥1 cells had expected counts <5). Multivariate logistic regression was executed using all parameters as independent variables, except where indicated, with calculated odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Values/statistics for each variable are given for cases with known data. All statistical analyses were carried out using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS; Build 1.0.0.1327; copyright 2019, IBM) with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Characteristics of mucinous neoplasms confined to the appendix

A total 337 specimens were included (Table 1) from 194 (57.6%) women and 143 (42.4%) men with median age of 58 years (IQR: 47–67). Thirty patients (8.9%) had IBD (16 ulcerative colitis, 13 Crohn disease and 1 indeterminate colitis). Indication for surgery was mass or mucocele in 163 (48.4%) and inflammation (including pain, appendicitis, obstruction, and intussusception) in 122 (36.2%) cases. In the remaining 52 (15.4%) patients, AMN was incidentally found in resections for IBD, gynecological diagnoses, or other nonneoplastic causes, including interval appendectomy. Index surgery was simple appendectomy (with or without concomitant cecectomy) in 258 (76.6%) cases and more extensive (ileocolic resection, right hemicolectomy, or total/subtotal colectomy) in 79 (23.4%) patients. Perforation of the appendix, described clinically (on pre-operative imaging) or grossly (during sectioning), was seen in 24 (7.1%) cases, none of which had dysplastic epithelium or acellular mucin on the serosa, after complete sectioning and review of all histologic slides. Appendiceal diverticulae (microscopically identified) were present in 50 (14.8%) specimens. Most AMNs were classified as low-grade (n = 322, 95.5%), but there were 15 (4.5%) cases with high-grade dysplasia (i.e., HAMN). The resection margin was histologically positive in 29 (8.6%) cases: in 21 cases due to neoplastic epithelium and in 8 cases due to acellular mucin. Lymph nodes were harvested in 102 (30.3%) cases comprising mostly extensive resections, but also some appendectomies with concomitant cecectomies yielding a few lymph nodes each. A median of 6.5 lymph nodes were obtained per specimen (IQR: 2–14) and a total of 910 lymph nodes were collected which were all negative for metastatic disease.

Depth of tumor involvement and associated parameters

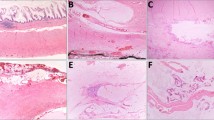

Based on inclusion criteria, all tumors were confined to the appendix. Histologic slides were available in 279 cases and all sections were reviewed by two GI pathologists to confirm the diagnosis and assess the deepest layer involved by tumor, including neoplastic epithelium or acellular mucin (Fig. 1). In 77 (27.6%) cases, muscularis mucosae was intact around the entire periphery of the neoplasm and these were classified as extending to mucosa. They were composed of villous or undulating dysplastic mucinous epithelium and demonstrated marked reduction or complete absence of lamina propria, with absence of epithelial serration and little or no cystic dilation. In 101 (36.2%) cases, tumor involved submucosa, occasionally pushing against, but not involving muscularis propria. In 33 (11.8%) cases, the neoplasm extended into, but not through, the muscularis propria and in the remaining 68 (24.4%) cases, the tumor was present in subserosal soft tissues, but did not involve the serosa (i.e., pT3).

A Low-power view of AMN involving mucosa only with dysplastic villous mucinous epithelium and obliterated lamina propria. B AMN that is also limited to the mucosa, however with focally preserved lamina propria. Note intact muscularis mucosae in both A, B. C Tumor that extends to the submucosa, evidenced by the absence of muscularis mucosae and its replacement by fibrosis. D AMN that is also classified as involving submucosa since acellular mucin abuts, but does not extend into, the muscularis propria. E Neoplasm with extension of acellular mucin into, but not through, muscularis propria. F AMN with acellular mucin involving subserosal soft tissue. Note the absence of muscle fibers between the tumor and serosal surface. Note that in cases D–F, there was convincing AMN present elsewhere in the specimen and the acellular mucin was interpreted as neoplastic in that context. Tumors in A–E would have been staged as pTis(LAMN) according to the AJCC, whereas the neoplasm in F would have been staged as pT320. (H&E stains; original magnification: ×20 in A, ×100 in B–E, ×40 in F).

In order to identify parameters that might be associated with tumor growth into the wall, we evaluated clinicopathologic characteristics in these four groups (Table 2). In univariate analysis, deeper tumor extension was associated with older age (p = 0.004), appendiceal specimens that were longer, wider, and with larger volume (p = 0.008, p < 0.001, and p < 0.001, respectively), and gross perforation (p = 0.031). In addition, cases with deeper tumor extension were more likely to have had presented with a mass or mucocele as the indication for surgery, compared to inflammatory causes or incidentally (p < 0.001). In contrast, tumor depth did not correlate with patient sex, resection type, co-existence of IBD, presence of appendiceal diverticulae, grade, or histologic status of the margin, nor were there any significant differences in number of lymph nodes harvested between the groups. In multivariate analysis, older age (p = 0.032; OR: 1.02 [95% CI: 1.00–1.03]), indication of mass or mucocele (p < 0.001; OR: 2.09 [95% CI: 1.41–3.11]), and larger appendix diameter (p < 0.001; OR: 1.61 [95% CI: 1.28–2.02]) remained significantly associated with deeper tumor extension.

Among these 279 reviewed neoplasms, those with low-grade dysplasia in the epithelium (i.e., LAMN; n = 269, 96.4%) did not significantly differ from those with high-grade dysplasia (i.e., HAMN; n = 10, 3.6%) in any of the variables examined, including tumor depth (Supplementary Table 1).

Patient outcomes

Types of treatment employed and patient outcomes, including tumor recurrence, development of peritoneal disease (PMP) and disease-specific mortality, were evaluated and compared between these subgroups for 194 patients who had clinical follow-up of at least 6 months, including 185 cases with low-grade and 9 cases with high-grade dysplasia (Table 3). Age remained correlated with tumor depth, with older patients being significantly associated with deeper tumor extension through the appendiceal wall (p = 0.011). During a median follow-up of 56.1 months (IQR: 24.4–98.5), there was not a single instance of disease recurrence, progression, or peritoneal involvement (i.e., PMP), in any of these tumor subgroups, which had similar follow-up intervals. Three patients in total received HIPEC, including one patient with tumor limited to the mucosa but grossly evident perforation of the appendix (who was described in the medical record as being given “prophylactic HIPEC”) and two patients with subserosal tumor extension (one with gross perforation and the other with appendiceal diverticulae). Among 29 patients with positive surgical margins, 7 cases (all with low-grade epithelium at the margin) underwent immediate follow-up surgery. Resulting specimens in these procedures (4 cecectomies, 2 ileocolic resections, and 1 right hemicolectomy) were completely negative in 4 cases, contained only acellular mucin in the appendiceal stump in 2 cases and low-grade epithelium (residual AMN) in only 1 case. None of these cases had tumor recurrence after the completion resections. Overall, 13 patients died during the course of the study, all from causes unrelated to appendiceal neoplasm (i.e., there was no disease-specific mortality).

Discussion

This study examined the pathologic characteristics and clinical outcomes of mucinous neoplasms confined to the appendix, subclassified according to anatomic layer of the wall involved. Deeper tumor extension was associated with older age, clinical indication of mass or mucocele and wider gross diameter of the appendix. However, there were no metastases in almost a thousand lymph nodes examined and no recurrence, peritoneal involvement (PMP), or disease-specific mortality in almost 5 years of median follow-up, including in cases of high-grade dysplasia. These data indicate that AMNs confined to the appendix behave in a benign fashion and portend an excellent prognosis, regardless of grade or tumor depth, and accordingly may have implications in terms of the nomenclature, staging, and, ultimately, clinical management of these neoplasms.

Most AMNs occur in adults in their sixth decade of life, as was the case in our cohort, which is not surprising given that the risk of harboring appendiceal neoplasms increases with age; some authors even recommend interval appendectomy in patients over 40 years-old for neoplasm risk reduction3,21,22,23,24. Specifically for AMNs, which are slow-growing with absent or non-specific and non-localizing symptoms, it is reasonable that tumors would grow deeper into the wall in older patients given that they are less likely to come to medical attention at a younger age, e.g., for acute appendicitis. Supporting this conclusion, tumors with deeper extension were also more likely to have mass or mucocele as the indication for surgery, consistent with an enlarging mass eventually recognized on an imaging modality such as a CT scan25. Deeper extension into the wall was also independently associated with wider diameter, suggesting that mucin-producing tumors lead to increased intraluminal pressure and cause circumferential growth. In addition, positive proximal resection margins were not associated with tumor depth, supporting the notion that AMNs grow radially rather than longitudinally. However, a recent study found that LAMNs developing PMP were significantly more likely to have smaller diameter than those that did not develop PMP26.

The most significant finding of this study is the fact that there was not a single event of tumor recurrence or progression (e.g., subsequent development of PMP) among these cases, reinforcing prior reports on the benign behavior of AMNs confined to the appendix. This is the largest such cohort with complete histologic evaluation of entirely submitted appendix specimens and follow-up of at least 6 months. The entire literature on these lesions, consisting of tumors without extension to the appendiceal serosa or beyond at presentation, comprises around 500 reported cases4,5,6,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. Among these, there have only been two documented instances of disease progression35,36. However, slides had not been available for review in all cases and specimens had not been entirely sectioned and submitted for histologic examination, casting doubt in terms of the correct staging of these two lesions as being truly confined to the appendix at presentation. Specimens with AMNs need to be entirely sectioned and examined histologically, in order to exclude more advanced disease. This is important since the staging of AMNs, both low- and high-grade, incorporates the maximum extent of tumor as determined by the presence of neoplastic epithelium or acellular mucin. Additionally, special care should be taken to avoid misinterpreting reactive hyperplastic changes, especially since they tend to occur in the post-inflammatory setting41. To safeguard against overdiagnosing reactive hyperplasia, we reviewed all slides in order to confirm the dysplastic nature of the epithelium, particularly in cases of interval appendectomy.

While reports in the surgical oncologic literature may not be particularly concerned with entirely sectioning the appendix or reviewing all slides in order to confirm true tumor depth, several recent publications have concluded that completely resected AMNs with no extra-appendiceal disease at presentation (whether due to dysplastic epithelium or acellular mucin) do not require continued surveillance35,36,37. In fact, there is evidence that some of these tumors are being inappropriately diagnosed and overtreated with risk for significant adverse side effects42. Three cases in our study received adjuvant HIPEC, despite being confined to the appendix, underscoring the importance of appropriate, consistent and universal pathologic reporting in order to effectively communicate and streamline postoperative treatment and surveillance in these patients. Nevertheless, there is ongoing debate and differing opinions on the proper postoperative management of these lesions, thus necessitating collection of additional data43,44. Hence, our study systematically documented the completely benign nature of these lesions, when confined to the appendix with intact serosa.

According to the AJCC classification of AMNs, grouped under carcinoma of the appendix, “by definition, LAMNs are associated with obliteration of the muscularis mucosae; a LAMN confined to the mucosa with intact muscularis mucosa is categorized as appendiceal adenoma”20. However, the WHO and PSOGI advocate that the term mucinous cystadenoma not be used1,3. Published guidelines only permit hyperplastic polyp, sessile serrated lesion and serrated dysplasia (low- and high-grade) as acceptable terminology for mucosal lesions, together with colorectal-type adenomas, which are exceedingly rare in the appendix45,46,47. This lack of clarity creates confusion when naming lesions surrounded by intact muscularis mucosae (as in Fig. 1A, B), which were the second most common subtype in our study. We agree with Yantiss et al., who have advocated for re-introducing the term mucinous adenoma to describe lesions composed of neoplastic proliferations of mucin-containing epithelial cells confined to the mucosa48,49. These lesions have been described as having markedly decreased or entirely lacking lamina propria, as was the case with all such neoplasms included herein. In this context, a positive surgical resection margin does not portend a worse clinical outcome as we and others have shown and as supported by data in this study4,27,37,39. In fact, identifying residual tumor in the appendiceal stump after a positive appendectomy margin is uncommon: there was only one such case in this study (out of seven cases with positive margin and follow-up surgery), while another study showed no residual tumor in six cecectomies27. Thus, given its lack of prognostic significance, margin status should not come into play or dictate whether the term mucinous adenoma is appropriate, as has been suggested6.

Importantly, nine cases of AMN with high-grade dysplasia (i.e., HAMNs) in our study also showed no evidence of progression. Given that these are molecularly similar to LAMNs, there is no reason for them to be staged differently, much less so by using criteria for invasive carcinoma of the appendix20,50. Prior studies have shown that HAMNs confined to the appendix have low risk of progression to PMP51. Our data double the number of reported cases, suggesting that they should not be considered worrisome beyond their cytologic features and that they should be staged similarly to LAMNs. In our data, there was no correlation between high-grade dysplasia and extent of tumor depth through the wall or any other characteristic, including diameter of the appendix.

To our knowledge, this is the first study specifically examining outcomes among AMNs according to depth of involvement (i.e., pT stage), showing invariably excellent prognosis when there is no serosal disease. Thus, it may be appropriate to modify nomenclature and staging guidelines for these tumors (Table 4). It seems intuitive that a lesion composed of dysplastic epithelium entirely surrounded by intact and recognizable muscularis mucosae with no risk of malignant progression should be termed adenoma. Conversely, if muscularis mucosae is not intact (whether due to pushing invasion or other situations precluding its confident evaluation, such as fibrosis, dissecting mucin, or perforation), then the terms adenoma or in situ (Tis) are inherently inconsistent and these lesions are best referred to as LAMN/HAMN. We further propose that they be assigned an appropriate pT stage, regardless of dysplasia grade, reflecting the anatomic layers of tumor extension through the wall (as is the case for other colorectal epithelial neoplasms). However, given that the risk of malignant progression in AMNs confined to the appendix is practically absent and in order to communicate their benign prognosis, they should be collectively assigned overall prognostic Stage Group 0. This proposed classification would eliminate discrepant staging of AMNs according to grade (as is currently the case), would stay true to the anatomic separation of intestinal wall layers dictating pT stage (as is used elsewhere in the colorectum), and would avoid awkward designations such as labeling tumors in situ (pTis) even when those are extending to the muscularis propria or egregious leaps from pTis to pT3 stages without intervening tiers. Pathologic staging would accurately project information on natural history in these neoplasms and clinicians would perform appropriate follow-up, avoiding unnecessary interventions, additional costs, and the adverse events that these may entail. If confirmed, this proposal can be embraced by organizations such as WHO, PSOGI, and AJCC in future iterations of nomenclature and staging guidelines.

In conclusion, we show that, among mucinous neoplasms confined to the appendix, deeper involvement through the appendiceal wall is associated with older age, indication of mass or mucocele, and wider specimen diameter, but does not confer any risk of disease recurrence or progression to PMP, including in cases of high-grade dysplasia and for tumors involving the subserosa. Thus, we propose that these neoplasms be staged and prognosticated distinctly from classic (infiltrating) carcinomas of the appendix. Mucinous neoplasms involving mucosa only (i.e., surrounded by intact muscularis mucosae) warrant the diagnostic term mucinous adenoma, whereas those extending through the wall, but without reaching the serosa, should be called LAMN/HAMN and staged according to similar pT definitions elsewhere in the colon, but with a designation of overall Stage Group 0, signifying their essentially benign nature.

Data availability

The de-identified dataset collected, used, and analyzed in this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Carr, N. J., Cecil, T. D., Mohamed, F., Sobin, L. H., Sugarbaker, P. H., Gonzalez-Moreno, S. et al. A Consensus for Classification and Pathologic Reporting of Pseudomyxoma Peritonei and Associated Appendiceal Neoplasia: The Results of the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) Modified Delphi Process. Am J Surg Pathol 40, 14-26 (2016).

Shaib, W. L., Goodman, M., Chen, Z., Kim, S., Brutcher, E., Bekaii-Saab, T. et al. Incidence and Survival of Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasms: A SEER Analysis. Am J Clin Oncol 40, 569-573 (2017).

Misdraji, J., Carr, N. J. & Pai, R. K. Tumours of the appendix: appendiceal mucinous neoplasm. In: I. D. Nagtegaal, D. S. Klimstra, & M. K. Washington (eds). Digestive System Tumours. WHO Classification of Tumours 143-146 (IARC: Lyon, 2019).

Ballentine, S. J., Carr, J., Bekhor, E. Y., Sarpel, U. & Polydorides, A. D. Updated staging and patient outcomes in low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Mod Pathol 34, 104-115 (2021).

Misdraji, J., Yantiss, R. K., Graeme-Cook, F. M., Balis, U. J. & Young, R. H. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: a clinicopathologic analysis of 107 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 27, 1089-1103 (2003).

Pai, R. K., Beck, A. H., Norton, J. A. & Longacre, T. A. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: clinicopathologic study of 116 cases with analysis of factors predicting recurrence. Am J Surg Pathol 33, 1425-1439 (2009).

Carr, N. J., Bibeau, F., Bradley, R. F., Dartigues, P., Feakins, R. M., Geisinger, K. R. et al. The histopathological classification, diagnosis and differential diagnosis of mucinous appendiceal neoplasms, appendiceal adenocarcinomas and pseudomyxoma peritonei. Histopathology 71, 847-858 (2017).

Carr, N. J., Emory, T. S. & Sobin, L. H. Epithelial neoplasms of the appendix and colorectum: an analysis of cell proliferation, apoptosis, and expression of p53, CD44, bcl-2. Arch Pathol Lab Med 126, 837-841 (2002).

Ronnett, B. M., Zahn, C. M., Kurman, R. J., Kass, M. E., Sugarbaker, P. H. & Shmookler, B. M. Disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis and peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis. A clinicopathologic analysis of 109 cases with emphasis on distinguishing pathologic features, site of origin, prognosis, and relationship to “pseudomyxoma peritonei”. Am J Surg Pathol 19, 1390-1408 (1995).

Szych, C., Staebler, A., Connolly, D. C., Wu, R., Cho, K. R. & Ronnett, B. M. Molecular genetic evidence supporting the clonality and appendiceal origin of Pseudomyxoma peritonei in women. Am J Pathol 154, 1849-1855 (1999).

Bradley, R. F., Stewart, J. H. T., Russell, G. B., Levine, E. A. & Geisinger, K. R. Pseudomyxoma peritonei of appendiceal origin: a clinicopathologic analysis of 101 patients uniformly treated at a single institution, with literature review. Am J Surg Pathol 30, 551-559 (2006).

Carr, N. J., Finch, J., Ilesley, I. C., Chandrakumaran, K., Mohamed, F., Mirnezami, A. et al. Pathology and prognosis in pseudomyxoma peritonei: a review of 274 cases. J Clin Pathol 65, 919-923 (2012).

Davison, J. M., Choudry, H. A., Pingpank, J. F., Ahrendt, S. A., Holtzman, M. P., Zureikat, A. H. et al. Clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of disseminated appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: identification of factors predicting survival and proposed criteria for a three-tiered assessment of tumor grade. Mod Pathol 27, 1521-1539 (2014).

Chua, T. C., Moran, B. J., Sugarbaker, P. H., Levine, E. A., Glehen, O., Gilly, F. N. et al. Early- and long-term outcome data of patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei from appendiceal origin treated by a strategy of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 30, 2449-2456 (2012).

Chua, T. C., Yan, T. D., Smigielski, M. E., Zhu, K. J., Ng, K. M., Zhao, J. et al. Long-term survival in patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei treated with cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: 10 years of experience from a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol 16, 1903-1911 (2009).

Gough, D. B., Donohue, J. H., Schutt, A. J., Gonchoroff, N., Goellner, J. R., Wilson, T. O. et al. Pseudomyxoma peritonei. Long-term patient survival with an aggressive regional approach. Ann Surg 219, 112-119 (1994).

Sugarbaker, P. H., Alderman, R., Edwards, G., Marquardt, C. E., Gushchin, V., Esquivel, J. et al. Prospective morbidity and mortality assessment of cytoreductive surgery plus perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy to treat peritoneal dissemination of appendiceal mucinous malignancy. Ann Surg Oncol 13, 635-644 (2006).

Misdraji, J. Mucinous epithelial neoplasms of the appendix and pseudomyxoma peritonei. Mod Pathol 28 Suppl 1, S67-79 (2015).

Arnold, C. A., Graham, R. P., Jain, D., Kakar, S., Lam-Himlin, D. M., Naini, B. V. et al. Knowledge gaps in the appendix: a multi-institutional study from seven academic centers. Mod Pathol 32, 988-996 (2019).

Overman, M. J., Asare, E. A., Compton, C. C., Hanna, N. H., Kakar, S., Kosinski, L. A. et al. Appendix: carcinoma. In: M. B. Amin (ed). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual 237-250 (Springer: New York, 2017).

Grasso, C. S. & Walker, L. A. Modern Management of the Appendix: So Many Options. Surg Clin North Am 101, 1023-1031 (2021).

Hayes, D., Reiter, S., Hagen, E., Lucas, G., Chu, I., Muniz, T. et al. Is interval appendectomy really needed? A closer look at neoplasm rates in adult patients undergoing interval appendectomy after complicated appendicitis. Surg Endosc 35, 3855-3860 (2021).

Fouad, D., Kauffman, J. D. & Chandler, N. M. Pathology findings following interval appendectomy: Should it stay or go? J Pediatr Surg 55, 737-741 (2020).

Mallinen, J., Rautio, T., Gronroos, J., Rantanen, T., Nordstrom, P., Savolainen, H. et al. Risk of Appendiceal Neoplasm in Periappendicular Abscess in Patients Treated With Interval Appendectomy vs Follow-up With Magnetic Resonance Imaging: 1-Year Outcomes of the Peri-Appendicitis Acuta Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg 154, 200-207 (2019).

Yu, X. R., Mao, J., Tang, W., Meng, X. Y., Tian, Y. & Du, Z. L. Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms confined to the appendix: clinical manifestations and CT findings. J Investig Med 68, 75-81 (2020).

Hegg, K. S., Mack, L. A., Bouchard-Fortier, A., Temple, W. J. & Gui, X. Macroscopic and microscopic characteristics of low grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (LAMN) on appendectomy specimens and correlations with pseudomyxoma peritonei development risk. Ann Diagn Pathol 48, 151606 (2020).

Arnason, T., Kamionek, M., Yang, M., Yantiss, R. K. & Misdraji, J. Significance of proximal margin involvement in low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Arch Pathol Lab Med 139, 518-521 (2015).

Foster, J. M., Sleightholm, R. L., Wahlmeier, S., Loggie, B., Sharma, P. & Patel, A. Early identification of DPAM in at-risk low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm patients: a new approach to surveillance for peritoneal metastasis. World J Surg Oncol 14, 243 (2016).

McDonald, J. R., O’Dwyer, S. T., Rout, S., Chakrabarty, B., Sikand, K., Fulford, P. E. et al. Classification of and cytoreductive surgery for low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Br J Surg 99, 987-992 (2012).

Wong, M., Barrows, B., Gangi, A., Kim, S., Mertens, R. B. & Dhall, D. Low-Grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasms: A Single Institution Experience of 64 Cases With Clinical Follow-up and Correlation With the Current (Eighth Edition) AJCC Staging. Int J Surg Pathol 28, 252-258 (2020).

Esquivel, J., Garcia, S. S., Hicken, W., Seibel, J., Shekitka, K. & Trout, R. Evaluation of a new staging classification and a Peritoneal Surface Disease Severity Score (PSDSS) in 229 patients with mucinous appendiceal neoplasms with or without peritoneal dissemination. J Surg Oncol 110, 656-660 (2014).

Umetsu, S. E., Shafizadeh, N. & Kakar, S. Grading and staging mucinous neoplasms of the appendix: a case series and review of the literature. Hum Pathol 69, 81-89 (2017).

Li, X., Zhou, J., Dong, M. & Yang, L. Management and prognosis of low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: A clinicopathologic analysis of 50 cases. Eur J Surg Oncol 44, 1640-1645 (2018).

Aleter, A., El Ansari, W., Toffaha, A., Ammar, A., Shahid, F. & Abdelaal, A. Epidemiology, histopathology, clinical outcomes and survival of 50 cases of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: Retrospective cross-sectional single academic tertiary care hospital experience. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 64, 102199 (2021).

Baumgartner, J. M., Srivastava, A., Melnitchouk, N., Drage, M. G., Huber, A. R., Gonzalez, R. S. et al. A Multi-institutional Study of Peritoneal Recurrence Following Resection of Low-grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasms. Ann Surg Oncol 28, 4685-4694 (2021).

Guaglio, M., Sinukumar, S., Kusamura, S., Milione, M., Pietrantonio, F., Battaglia, L. et al. Clinical Surveillance After Macroscopically Complete Surgery for Low-Grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasms (LAMN) with or Without Limited Peritoneal Spread: Long-Term Results in a Prospective Series. Ann Surg Oncol 25, 878-884 (2018).

Gupta, A. R., Brajcich, B. C., Yang, A. D., Bentrem, D. J. & Merkow, R. P. Necessity of posttreatment surveillance for low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. J Surg Oncol 124, 1115-1120 (2021).

Reiter, S., Rog, C. J., Alassas, M. & Ong, E. Progression to pseudomyxoma peritonei in patients with low grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms discovered at time of appendectomy. Am J Surg https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.12.003 (2021).

Tiselius, C., Kindler, C., Shetye, J., Letocha, H. & Smedh, K. Computed Tomography Follow-Up Assessment of Patients with Low-Grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasms: Evaluation of Risk for Pseudomyxoma Peritonei. Ann Surg Oncol 24, 1778-1782 (2017).

Bell, P. D., Huber, A. R., Drage, M. G., Barron, S. L., Findeis-Hosey, J. J. & Gonzalez, R. S. Clinicopathologic Features of Low-grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm: A Single-institution Experience of 117 Cases. Am J Surg Pathol 44, 1549-1555 (2020).

Hissong, E., Goncharuk, T., Song, W. & Yantiss, R. K. Post-inflammatory mucosal hyperplasia and appendiceal diverticula simulate features of low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Mod Pathol 33, 953-961 (2020).

Choudry, H. A., Pai, R. K., Parimi, A., Jones, H. L., Pingpank, J. F., Ahrendt, S. S. et al. Discordant Diagnostic Terminology and Pathologic Grading of Primary Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasms Reviewed at a High-Volume Center. Ann Surg Oncol 26, 2607-2614 (2019).

Gupta, A. R., Brajcich, B. C. & Merkow, R. P. Postoperative LAMN surveillance recommendations. J Surg Oncol 125, 546-547 (2022).

Campana, L. G., Wilson, M. S., Halstead, R., Wild, J. & O’Dwyer, S. T. The need for tailored posttreatment surveillance for low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (LAMN). J Surg Oncol 125, 317-319 (2022).

Limaiem, F., Arfa, N., Marsaoui, L., Bouraoui, S., Lahmar, A. & Mzabi, S. Unexpected Histopathological Findings in Appendectomy Specimens: a Retrospective Study of 1627 Cases. Indian J Surg 77, 1285-1290 (2015).

Yilmaz, M., Akbulut, S., Kutluturk, K., Sahin, N., Arabaci, E., Ara, C. et al. Unusual histopathological findings in appendectomy specimens from patients with suspected acute appendicitis. World J Gastroenterol 19, 4015-4022 (2013).

Ma, K. W., Chia, N. H., Yeung, H. W. & Cheung, M. T. If not appendicitis, then what else can it be? A retrospective review of 1492 appendectomies. Hong Kong Med J 16, 12-17 (2010).

Hissong, E. & Yantiss, R. K. The Frontiers of Appendiceal Controversies: Mucinous Neoplasms and Pseudomyxoma Peritonei. Am J Surg Pathol 46, e27-e42 (2022).

Orr, C. E. & Yantiss, R. K. Controversies in appendiceal pathology: Mucinous and goblet cell neoplasms. Pathology https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pathol.2021.09.003 (2021).

Liao, X., Vavinskaya, V., Sun, K., Hao, Y., Li, X., Valasek, M. et al. Mutation profile of high-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm. Histopathology 76, 461-469 (2020).

Singhal, S., Giner-Segura, F., Barnes, T. G., Hompes, R., Guy, R. & Wang, L. M. The value of grading dysplasia in appendiceal mucinous neoplasm in the absence of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Histopathology 73, 351-354 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.D.P. and X.W.: study concept and design; methodology development; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; statistical analysis; writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by our Institutional Review Board (#18-00479) as exempt from the requirement for consent and was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Polydorides, A.D., Wen, X. Clinicopathologic parameters and outcomes of mucinous neoplasms confined to the appendix: a benign entity with excellent prognosis. Mod Pathol 35, 1732–1739 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-022-01114-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-022-01114-7