Abstract

With the increasing demand for multispectral information acquisition, infrared multispectral imaging technology that is inexpensive and can be miniaturized and integrated into other devices has received extensive attention. However, the widespread usage of such photodetectors is still limited by the high cost of epitaxial semiconductors and complex cryogenic cooling systems. Here, we demonstrate a noncooled two-color infrared photodetector that can provide temporal-spatial coexisting spectral blackbody detection at both near-infrared and mid-infrared wavelengths. This photodetector consists of vertically stacked back-to-back diode structures. The two-color signals can be effectively separated to achieve ultralow crosstalk of ~0.05% by controlling the built-in electric field depending on the intermediate layer, which acts as an electron-collecting layer and hole-blocking barrier. The impressive performance of the two-color photodetector is verified by the specific detectivity (D*) of 6.4 × 109 cm Hz1/2 W−1 at 3.5 μm and room temperature, as well as the promising NIR/MWIR two-color infrared imaging and absolute temperature detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-color infrared (IR) technology can identify targets in a complex environment by using the multispectral features of targets, and this technique has been widely used in information technology, life sciences, aerospace, and other fields1,2,3,4,5. As this technology has been developed, the main research direction has become the integration of two-color detection into single pixels without complex optical components6 while solving the core problem of separating and detecting dual spectral information independently7. Early techniques for obtaining the information from two bands involved a photodetector unit composed of multiple pixels with different response spectra in the plane, but poor spatial consistency led to aberrations in imaging. In 1980, a structure based on a back-to-back concept with three electrodes was designed8 to solve the problem of spatial coexcitation, but this strategy results in poor temporal coherence during sequential detection, which makes it very difficult to detect a moving target9. Since then, the simultaneous temporal-spatial mode of two-color IR photodetectors has been a popular research topic and has been successfully implemented in HgCdTe (MCT)10, quantum wells11, type II superlattices12 and so on. However, these conventional two-color IR photodetectors require complex cryogenic cooling systems to reduce dark current13, and their active-layer materials are more or less facing lattice mismatch at the interface in the process of multilayer heteroepitaxy, against the requirement of low-crosstalk and miniaturization applications7. Therefore, there is much interest in new IR materials and structures that fill gaps in the existing field.

Two-dimensional (2D) materials have shown infinite potential for use in future IR photodetectors14,15,16,17. Different from conventional thin-film materials, layered 2D materials exhibit van der Waals (vdWs) bonding18 and can therefore be stacked in any number of layers regardless of lattice mismatching19, the deposition temperature and dangling surface bonds20, which makes them promising for integration with mature 3D material systems21,22,23,24,25,26. Therefore, the band at the interface of the vdWs heterojunction can change abruptly with sharp band edges, which makes it possible to assemble devices with well-designed bands27,28. More importantly, layered 2D materials do not incur defects induced by internal stress29; therefore, the dark current induced by crystal surface defects and thermal ionization is reduced, indicating high potential for use in IR photodetection at room temperature30,31,32,33,34. Here, we designed a vertically stacked back-to-back 2D/3D hybrid photodetector with a black phosphorus (bP)/molybdenum sulfide (MoS2)/silicon (Si) vdWs heterostructure for use in temporal-spatial coexisting NIR/MWIR two-color blackbody sensitive photodetectors with ultralow crosstalk of ~0.05% at room temperature. Two built-in electric fields with opposite directions were successfully introduced by constructing a p-n-p- junction with a back-to-back structure, achieving the separation and detection of photogenerated carriers in two bands. Finite-element simulation was also utilized to optimize the band structure to reduce optical and electrical crosstalk. We demonstrated absolute temperature detection and IR imaging in two colors, indicating the reliability and application prospects of vdWs heterojunctions based on silicon technology in two-color photodetection.

Results

Design of the van der Waals two-color infrared photodetector

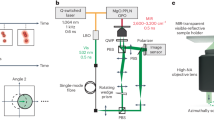

A diagram of a two-color photodetector with a p-n-p structure is shown in Fig. 1a. P-type bP was combined with n-type MoS2 to form a bP/MoS2 p-n junction for MWIR detection; the bP/MoS2 p-n junction was transferred onto the etched window of p-type thin-film Si to form a MoS2/Si n-p junction for NIR detection, resulting in a vertical vdWs heterostructure of bP/MoS2/Si. The vdWs heterostructures were built by the dry transfer method35 with mechanical stripping and stacking. More details of the fabrication can be found in the Methods section and Supplementary Information. Operating under back irradiation conditions, the photodetector performance was measured by using the circuit configuration shown in Fig. 1b. In its vertical structure, n-type MoS2 plays the role of electron collection and hole barrier layer, while p-type Si and bP are used to absorb NIR and MWIR radiation, respectively, resulting in spatially consistent two-color detection. Under NIR illumination, photogenerated electron-hole pairs are separated by the built-in electric field (E1) of the MoS2/Si heterojunction, pushing electrons to flow through the electrode via MoS2 and holes to flow through the electrode via p-Si, while the same processes occur at the bP/MoS2 heterojunction under MWIR radiation. Figure 1e shows the simulated band diagram of bP/MoS2/Si with p-Si applied at a negative voltage, suggesting that its key advantage is generating and collecting photogenerated holes in the NIR and MWIR bands independently at the junctions of Si/MoS2 and bP/MoS2, respectively. This leads to little electrical crosstalk. A pseudocolor transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of a completed device is shown in Fig. 1c, d. The layered characteristics of bP and MoS2 are obvious, with the intervals of a single layer being 5.5 and 6 Å, respectively. The high-resolution TEM images show that the interface between the bp/MoS2 atomic layers was clean without any contamination or amorphous oxide being generated during the fabrication. Because bP is easily oxidized, we also measured oxygen at the bp/MoS2 interface, and EDS mapping results showed no oxygen or organic matter (Fig. S3a). The whole process involving the device was carried out in a nitrogen glove box, so almost no oxide layer or organic matter was present at the Si/MoS2 interface (Fig. S3b), which greatly improved the performance of the device.

a Schematic of van der Waals two-color infrared photodetector, showing the working mode and external circuit of the photodetector. b Circuit configuration of device to demonstrate the performance of two-color photodetector. c Cross-sectional TEM image showing the bP/MoS2 interface. d Cross-sectional TEM image showing the Si/MoS2 interface. e Simulated energy band diagram with p-Si applied a negative voltage

Two-color performance characterization

We separately evaluated the bP/MoS2 heterojunction of the photodetector with MWIR irradiation and the MoS2/Si heterojunction with NIR irradiation. The I–V curve characteristics of the bP/MoS2 heterojunction without illumination at 300 K are shown in Fig. 2a, illustrating a typical rectification characteristic of the p-n junction. The inset of Fig. 2a displays the relation between current density and voltage (J-V curves) under dark and 1200 K blackbody illumination, revealing a typical photovoltaic mode for the MWIR photoresponse. Figure 2b shows the I–V curve characteristics of the MoS2/Si heterojunction without illumination at 300 K. As a reverse bias voltage is applied, E1 is strengthened, and the depletion region is enlarged. The inset of Fig. 2b shows the J-V curves of the MoS2/Si heterojunction under dark conditions and 1200 K blackbody illumination at negative bias.

a Dark current characteristics of bP/MoS2 heterojunction photodiode in 300 K without illumination. Inset: the J-V characteristics of the device with or without a 1200 K blackbody source. b Dark current characteristics of Si/MoS2 heterojunction photodiode in 300 K without illumination. Inset: the J-V characteristics of the device with or without a 1200 K blackbody source. c Specific detectivity at different blackbody temperatures. d Normalized spectral response of the two-color photodetector during the back radiation. The 0.7–1.3 μm of the spectrum was measured by a grating spectrometer. The 1.3–4.5 μm of the spectrum was measured by FTIR. All FTIR and laser diode characterization were performed at a bias of 0 V (MWIR) and −0.5 V (NIR). e Specific detectivity as a function of wavelength measured for a bP/MoS2/Si heterojunction at room temperature as well as various commercially available and reported NIR/MWIR two-color photodetectors, including MCT/Si (Kunming Institute of Physics), InGaAs/Si (Hamamatsu K1713-08) and InAsSb/Si (Hamamatsu K1713-003). All FTIR and laser diode characterization was performed at a bias of 0 V. The black line in the figure is the performance limit of photovoltaic devices; the red line is the performance limit of thermoelectric device; the gray box is commercial thermistor. f Left axis, NIR and MWIR signals as a function of photodetector–blackbody distance. Right axis, the relationship between the NIR/MWIR ratio and photodetector–blackbody distance. g NIR/MWIR ratio depends on the blackbody temperature. Red dots show the measured NIR/MWIR ratio in each blackbody temperature

Specific detectivity D* is the key parameter for characterizing the photosensitive performance of IR photodetectors36 and can be calculated by the following equation:

where In is the noise current, R is the responsivity, A is the effective area of the photodetector, and Δf is the bandwidth. The noise current is dominated by several types of noise, including Johnson noise, shot noise and background fluctuation-induced noise. To date, no IR photodetector operating at room temperature can reach the performance limit of background fluctuation; therefore, the background fluctuation-induced noise can be neglected. However, the dominant source of noise current is different for our photodetector with two operating modes.

In MWIR band detection, the dominant noise in the photodetector is Johnson noise because there is no additional driving power. In this method, the calculation for photodiodes with zero bias usually requires the extraction of zero-bias resistance R0 (extracted from the I–V measurements)36:

where η is the external quantum efficiency, λ is the wavelength, q is the elementary charge, h is the Planck constant, c is the speed of light, k is the Boltzmann constant, T is the photodetector temperature, and \(R_{{{\mathrm{0}}}}\) is the zero-bias resistance. From this, \(D_0^ \ast\) of the MWIR photodetection at 1200 K blackbody is calculated to be 1.78 × 109 cm Hz1/2 W−1.

For NIR, the noise in the photodetector under reverse bias is dominated by shot noise (much greater than Johnson noise)36. \(D_R^ \ast\) can be calculated by:

where \(I_D\) is the dark current. Therefore, the calculated \(D_R^ \ast\) of the NIR photodetector with a 1200 K blackbody is 9.8 × 108 cm Hz1/2 W−1. \(D^ \ast\) of the device decreases with decreasing blackbody temperature, as shown in Fig. 2c. This is due to the redshift in the peak wavelength caused by the decrease in the blackbody temperature, and the radiation power is greatly reduced.

We further conducted spectral photoresponse measurements at room temperature for the two-color IR photodetector, as shown in Fig. 2d, with a Fourier transform IR (FTIR) spectrometer and grating spectrometer. The cut-off wavelengths in the NIR and MWIR ranges were 0.9 and 3.9 μm, respectively. The peak detectivity in the MWIR range was 6.4 × 109 cm Hz1/2 W−1 at 3.5 μm (Fig. S6c) and was almost constant despite blackbody temperature changes, showing good stability and adaptability (Fig. 2c). The D*(λ) of the photodetector is comparable to that of commercialized noncooled NIR/MWIR two-color photodetectors, which indicates the application prospects of 2D vdWs heterostructures for use in IR photodetectors operating at room temperature (Fig. 2e). Figure S7 shows the measured noise current spectra of MWIR and NIR. According to the directly measured noise, the D* values calculated according to Eq. (1) were 3.51 × 109 cm Hz1/2 W−1 (MWIR at 3.5 μm) and 3.34 × 108 cm Hz1/2 W−1 (NIR), respectively. In this value, D* calculated from Id and R0 has good consistency. Moreover, the monochromatic photoresponse and low-temperature performance of the device was verified by the laser. The detailed information can be found in Fig. S9. Figure S8 shows the response time of the detector in microseconds and the linear dynamic range greater than 70 dB.

Colorimetric temperature measurement

Two-color IR photodetectors are widely used for temperature measurement and provide more reliable and accurate detection than single-band photodetectors2. With increasing object temperature, the radiation intensity over the whole spectrum increases, and the peak shifts to shorter wavelengths, as shown by Planck’s law (Fig. S5a). According to Planck’s law under the Wien approximation, the monochromatic emission power M is:

where ε is the emissivity, h is the Planck constant, c is the light speed, λ is the wavelength, Δλ is the wavelength width, k is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the photodetector temperature. For single temperature measurements, information on the emissivity and distance to the heat source is needed to determine the temperature of the object. However, in real measurements, the emissivity and distance to the heat source are often unknown. A two-color temperature measurement can eliminate the error associated with emittance and distance. Two-color temperature measurement is based on the ratio of two adjacent wavelengths of the IR radiation energy R to determine the temperature of the target object:

where C1 and C2 are the system constants. The reason for selecting adjacent wavelengths is that the epsilon of the adjacent wavelength of the emissivity rate is roughly the same; under certain conditions ε1/ε2, at the same time, and under the same detection range, its radiation power attenuation ratio is approximately the same. Therefore, the two-color photodetector can measure the absolute temperature by using the dual band information, regardless of the distance and emittance of the object, as shown in the schematic diagram of the temperature measurement setup in Fig. S4. Distance-dependent performance testing was performed to verify the influence of emission and radiation power attenuation at various distances on signal detection, and the result is shown in Fig. 2f. The NIR/MWIR signal ratio is almost a constant for a given temperature, independent of the radiation power and distance, so the value can correspond to the absolute temperature of the target at any distance. In addition, we varied the target temperature to verify the performance, as shown in Fig. 2g, revealing the corresponding relationship between the NIR/MWIR signal ratio and temperature. The signal ratio increased from 0.018 to 0.45 as the blackbody temperature increased from 850 to 1200 K. The temperatures of heat sources A and B were 923 and 1123 K, respectively, and the corresponding ratios obtained by the photodetector were 0.068 and 0.25. According to the fitting curve in Fig. 2g, corresponding ratios of 0.068 and 0.25 were calculated, and the detection temperatures were 930 and 1132 K, respectively, with the error being within the allowable range of the system. These results show that the two-color photodetector can remotely measure the temperature of a target heat source on the basis of the response ratio. Figure S5b shows the relationship between blackbody D* and radiant power. Under the same blackbody temperature, the D* of the device did not change with the change in blackbody radiation power. The operating frequency of the two-color photodetector reached 200 Hz, while the NIR/MWIR ratio remained constant, as shown in Fig. S12a. The repeatability of the measurement is shown in Fig. S13.

Crosstalk simulation and characterization

For distinguishing signals, crosstalk is an important index of a two-color photodetector. The crosstalk in a two-color photodetector consists of optical crosstalk and electrical crosstalk7. Optical crosstalk refers to the response of the MWIR layer to NIR light that is not fully absorbed by the NIR absorption layer. Electric crosstalk refers to the nonequilibrium carrier diffusion between the two absorption layers. Specifically, there are two kinds of crosstalk in this device. CNIR to MWIR (crosstalk of NIR to MWIR) is defined as the signal ratio of two junction signals of the NIR photodetector under MWIR radiation, which is mainly caused by electric crosstalk. CMWIR to NIR (crosstalk of MWIR to NIR) is defined as the signal ratio of the MWIR photodetector under NIR radiation, which is mainly caused by combined optical and electric crosstalk (Fig. S14).

For electric crosstalk, the electric field distribution and photocurrent distribution were studied by finite-element simulations. Different doping concentrations of Si can affect the internal electric field distribution. The band diagram for heavy Si doping is shown in Fig. 3a, and the CNIR to MWIR for heavy Si doping under the same conditions was very large. Figure 3b shows that the heavily doped Si/MoS2 depletion region was mainly distributed in MoS2, leading to overlap of the two depletion regions, and the signal generated by the MWIR junction was received by both the MWIR and NIR electrodes. These test results show that the crosstalk could not be suppressed, as shown in Fig. 3c. For light Si doping (1015 cm−3), the band diagram is shown in Fig. 3d. The depletion regions of the NIR and MWIR photodiodes were distributed in Si and bP, respectively (Fig. 3e). The depletion region was effectively blocked by the intermediate layer, which formed a barrier to block photogenerated holes, resulting in ultralow electrical crosstalk in the device (Fig. 3f). Therefore, MWIR-to-NIR crosstalk of 1.2% and NIR-to-MWIR crosstalk of 0.05% were obtained from Eqs. (7) and (8), respectively.

a Band diagram and depletion region distribution of heavily doped Si two-color devices in working mode. b Electric field distribution of heavily doped Si two-color devices in working mode. c Photocurrent of heavily doped Si two-color photodetector under a modulated illumination source (λ = 2 μm). Red and blue line are MWIR and NIR photocurrents, respectively. d Band diagram and depletion region distribution of light doped Si two-color devices in working mode. e Electric field distribution of light doped Si two-color devices in working mode. f Photocurrent of light doped Si two-color photodetector under a modulated illumination source (λ = 2 μm). g Photocurrent of light doped Si two-color photodetector under a modulated illumination source (White light) in front radiation mode. h Photocurrent of light doped Si two-color photodetector under a modulated illumination source (White light) in back radiation mode. i Crosstalk performance of bP/MoS2/Si devices and various reported two-color photodetectors

The optical crosstalk was analysed by white light irradiation in front irradiation mode and back irradiation mode. In front irradiation mode, the MWIR device absorbed white light directly, so there was considerable optical crosstalk (Fig. 3g). The two-color photodetector in this paper used back irradiation, in which NIR absorber materials effectively absorbed NIR radiation and greatly reduced the optical crosstalk (Fig. 3h). Compared with the frontal incident mode, the CMWIR to NIR decreased from 11.24% to 1.2% by integrating over the spectral coincidence area, as shown in Fig. S11a. To further verify the low crosstalk of the vdWs two-color photodetector, we compared the crosstalk in our device with that in other structures. Figure 3i shows the comparison of the two-color crosstalk in the vdWs two-color photodetector (red line) and commercial devices. The vdWs two-color photodetector exhibited ultralow two-color crosstalk compared to the integrated two-color photodetector based on conventional materials.

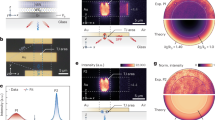

Temporal-spatial coexisting two-color IR imaging

After calibrating the temperature recognition function of the device, a two-color imaging experiment was carried out. A blackbody-like radiant heat source was used as the target to verify the two-color detection capability of our device37. Figure 4a displays a schematic diagram of the imaging setup, and the two-color photodetector was used to replace the detecting chip of a camera. An image was acquired by two-dimensional scanning and converting the output voltage of each pixel into a gray value. Two output channels were used to ensure the simultaneous acquisition of both bands in the imaging. To better understand the two-color performance, we constructed a complex scene in which a Si wafer was placed in front of the heat target, as shown in Fig. 4b, c. Two opposite built-in electric fields can detect the photogenerated carriers from the two bands independently, which was enabled by the vertical structure. The photodetector showed high temporal and spatial consistency in the two-color detection. The NIR and MWIR imaging results were captured as shown in Fig. 4d, e. Here, the results are attributed to the high dynamic range imaging capability of the two-color photodetector, which is a key feature of high-quality imaging. On the other hand, the lower half of the target was not detected because the light does not penetrate Si, as shown in the NIR imaging results (Fig. 4d). Therefore, in a complex environment, a two-color photodetector can obtain more target information than single-color imaging and detect the temperature of the target at the same time as two-color imaging. The photocurrents IN and IM were extracted from the two-color image, and the signal ratio of the heating tube was 0.625. Based on Fig. 3c, the temperature of the heating tube was ~1257 K, which was very close to the actual temperature of 1300 K. Interestingly, commercial handheld IR thermometers could not identify the internal temperature of the resistance wire because the glass shell of the heating tube blocked the heat emitted by the carbon fiber heating wire (Fig. S17). These results show that a two-color image can provide more information than a single-band image.

a Schematic diagram of simultaneous mode two-color imaging system. Inset: optical image of two-color vdWs infrared photodetector. b Photograph of target (carbon fiber heating tube) was captured by a silica-based camera. c Photograph of target (carbon fiber heating tube covered by silicon wafer) was captured by a silica-based camera. d NIR images of objects behind a silicon wafer. The black dotted circle marks the position of the silicon wafer. The white dotted box indicates the location of photocurrent IN extraction. e MWIR images of objects behind a silicon wafer. The white dotted circle marks the position of the silicon wafer. The white dotted box indicates the location of photocurrent IM extraction

Discussion

In this study, we systematically investigated vdWs heterostructure-based multispectral detection to design and fabricate a two-color IR photodetector based on the p-n-p- vertical structure of bP/MoS2/Si and found impressive room-temperature specific detectivity D* of 6.4 × 109 cm Hz1/2 W−1 at 3.5 μm under blackbody radiation. The photogenerated carriers in two bands are successfully separated by two opposite built-in electric fields. The ultralow crosstalk of 1.2% for MWIR-to-NIR and 0.05% for NIR-to-MWIR due to the filtering effect of thin-film Si and the barrier effect of MoS2 ensures the independent readout of the dual band information. Moreover, calibration of the response under both the NIR and MWIR bands can be used to determine the absolute temperature of a heat source regardless of the detection distance and emissivity. Simultaneous imaging of the NIR and MWIR bands and imaging temperature detection were demonstrated. Compatible with existing silicon technology, vdWs heterojunctions can enable room-temperature IR two-color detection because of their novel device structure and energy band design, which is expected to improve current multispectral IR detection technologies.

Methods

Device fabrication

The bP/MoS2/Si vdWs heterostructure was fabricated by the dry transfer method. The 2D materials were mechanically exfoliated from bulk materials supplied by Smart Elements, HQ graphene. A detailed description of this process is provided in Supplementary Section 1. The exfoliation and transfer processes were carried out in a N2-protected glovebox to decrease the oxidation of the material. Electrode contact was defined using electron beam lithography, and Cr/Au (15/80 nm) was deposited using thermal evaporation. Before measurement, a thin PMMA layer was coated to protect the device from exposure to air and water.

Photodetector performance

The simulation structure consisted of a 200 nm p-type black phosphorus layer, a 50 nm n-type MoS2 layer, and a 200 nm p-type Si layer. The doping concentrations were assumed to be 5 × 1015 cm−3 black phosphorus, 1 × 1017 cm−3 MoS2, 1 × 1018 cm−3 Si (high doping), and 1 × 1015 cm−3 Si (low doping). The electronic characteristics were measured by an Agilent B2902A source. Blackbody testing was performed using a calibrated commercial blackbody furnace (HFY-206A). After the frequency was modulated by an optical chopper wheel, the photocurrent signal was converted into a voltage signal using a current preamplifier (Stanford Research Systems SR570) and recorded by a lock-in amplifier (Ametek Model 7270 DSP). The laser spectral response test was carried out by a combination of a continuous laser light source (YSL sc-pro) and gratings. The IR spectrum test adopted in this experiment was carried out by an FTIR spectrometer (Nicolet 8700), and globar light (1000 K blackbody) was used as the internal light source at room temperature. In all the photocurrent measurements, the laser (2000 nm) was focused on the device through a fixed optical path using a 20× objective lens (NA = 0.45) with a laser spot diameter of ~20 μm. The mid-IR laser responses of the photodetectors were tested by a mid-IR plasma laser with tuneable wavelengths (2.6, 3.1, 4, and 4.2 μm). The transient photocurrent response (at 2000 nm) was recorded using an oscilloscope (Tektronix DPO 5204) to analyse the photoresponse time. All measurements were performed at room temperature in an ambient environment. Electrical simulations were performed using the finite-element method.

References

Rogalski, A., Antoszewski, J. & Faraone, L. Third-generation infrared photodetector arrays. J. Appl. Phys. 105, 091101 (2009).

Tang, X., Ackerman, M. M., Chen, M. & Guyot-Sionnest, P. Dual-band infrared imaging using stacked colloidal quantum dot photodiodes. Nat. Photon 13, 277–282 (2019).

Xiong, J. & Wu, S.-T. Planar liquid crystal polarization optics for augmented reality and virtual reality: from fundamentals to applications. eLight 1, 3 (2021).

Jin, Z. et al. Phyllotaxis-inspired nanosieves with multiplexed orbital angular momentum. eLight 1, 5 (2021).

Chang, X., Bian, L. & Zhang, J. Large-scale phase retrieval. eLight 1, 4 (2021).

Martyniuk, P., Antoszewski, J., Martyniuk, M., Faraone, L. & Rogalski, A. New concepts in infrared photodetector designs. Appl. Phys. Rev. 1, 41102 (2014).

Hu, W. et al. 128 × 128 long-wavelength/mid-wavelength two-color HgCdTe infrared focal plane array detector with ultralow spectral cross talk. Opt. Lett. 39, 5184–5187 (2014).

Campbell, J. C., Dentai, A. G., Lee, T. P. & Burrus, C. A. Improved 2-wavelength demultiplexing InGaAsP photodetector. IEEE J. Quantum Electron 16, 601–603 (1980).

Smith, E. P. G. et al. Fabrication and characterization of two-color midwavelength/long wavelength HgCdTe infrared detectors. J. Electron. Mater. 35, 1145–1152 (2006).

Rajavel, R. D. et al. Molecular beam epitaxial growth and performance of HgCdTe-based simultaneous-mode two-color detectors. J. Electron. Mater. 27, 747–751 (1998).

Sarusi, G. QWIP or other alternative for third generation infrared systems. Infrared Phys. Technol. 44, 439–444 (2003).

Haddadi, A., Chevallier, R., Chen, G., Hoang, A. M. & Razeghi, M. Bias-selectable dual-band mid-/long-wavelength infrared photodetectors based on InAs/InAs1-xSbx type-II superlattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 011104 (2015).

Rogalski, A. HgCdTe infrared detector material: history, status and outlook. Rep. Prog. Phys. 68, 2267–2336 (2005).

Wang, Y. et al. Air-stable low-symmetry narrow-bandgap 2D sulfide niobium for polarization photodetection. Adv. Mater. 32, 2005037 (2020).

Tong, L. et al. Stable mid-infrared polarization imaging based on quasi-2D tellurium at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 11, 2308 (2020).

Xia, F., Wang, H. & Jia, Y. C. Rediscovering black phosphorus as an anisotropic layered material for optoelectronics and electronics. Nat. Commun. 5(6), 4458 (2014).

Wang, Z. et al. Controllable Doping in 2D Layered Materials. Adv. Mater. 33, 2104942 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Van der Waals heterostructures and devices. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16042 (2016).

Xia, F., Wang, H., Hwang, J. C. M., Neto, A. H. C. & Yang, L. Black phosphorus and its isoelectronic materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 306–317 (2019).

Jariwala, D., Marks, T. J. & Hersam, M. C. Mixed-dimensional van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Mater. 16, 170–181 (2017).

Behura, S. K., Wang, C., Wen, Y. & Berry, V. Graphene-semiconductor heterojunction sheds light on emerging photovoltaics. Nat. Photon 13, 312–318 (2019).

Liu, Y., Huang, Y. & Duan, X. F. Van der Waals integration before and beyond two-dimensional materials. Nature 567, 323–333 (2019).

Akinwande, D. et al. Graphene and two-dimensional materials for silicon technology. Nature 573, 507–518 (2019).

Chen, Z. & Segev, M. Highlighting photonics: looking into the next decade. eLight 1, 2 (2021).

Tong, L. et al. 2D materials-based homogeneous transistor-memory architecture for neuromorphic hardware. Science 373, 1353–1358 (2021).

Miao, J. et al. Gate-Tunable Semiconductor Heterojunctions from 2D/3D van der Waals Interfaces. Nano Lett. 20, 2907–2915 (2020).

Chhowalla, M., Jena, D. & Zhang, H. Two-dimensional semiconductors for transistors. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 15 16052 (2016).

Xiong, X. et al. A transverse tunnelling field-effect transistor made from a van der Waals heterostructure. Nat. Electron. 3, 106–112 (2020).

Lee, C., Wei, X., Kysar, J. W. & Hone, J. Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science 321, 385–388 (2008).

Bullock, J. et al. Polarization-resolved black phosphorus/molybdenum disulfide mid-wave infrared photodiodes with high detectivity at room temperature. Nat. Photon 12, 601–607 (2018).

Long, M. et al. Palladium diselenide long-wavelength infrared photodetector with high sensitivity and stability. ACS Nano 13, 2511–2519 (2019).

Tan, C. et al. Evaporated SexTe1-x thin films with tunable bandgaps for short-wave infrared photodetectors. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001329 (2020).

Meng, P. et al. Blackbody sensitive room-temperature infrared photodetectors based on low-dimensional tellurium grown by chemical vapor deposition. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf7358 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Unipolar barrier photodetectors based on van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Electron. 4, 357–363 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. One-dimensional electrical contact to a two-dimensional material. Science 342, 614–617 (2013).

Rogalski, A. Infrared detectors (CRC press, 2010).

Wang, P. et al. Arrayed van der Waals broadband detectors for dual-band detection. Adv. Mater. 29, 1604439 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62122081, 61905266, 62134009, 61725505, 11734016, 61974050), Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS, and Fund of Shanghai Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 21JC1406100, 19YF1454600 and 19XD1404100).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.H., P.Z., and P.W. conceived the project and designed the experiments. P.S.W., L.Y., and L.T. carried out most of the experiments and analysed the data. H.N.G. and Y.G. contributed to the theoretical calculations. Y.W., Z.W., M.P., Y.Y.Y., and F.W. analysed the data. Y.W. carried out the AFM measurements. K.Z. conducted the blackbody measurements. M.H. conducted the FTIR measurements. H.L.W. conducted the imaging measurements. W.H. was responsible for project planning. P.S.W., P.W., P.Z. and W.H. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, P., Ye, L., Tong, L. et al. Van der Waals two-color infrared photodetector. Light Sci Appl 11, 6 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-021-00694-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-021-00694-4

This article is cited by

-

On-chip optoelectronic logic gates operating in the telecom band

Nature Photonics (2024)

-

A neuromorphic bionic eye with filter-free color vision using hemispherical perovskite nanowire array retina

Nature Communications (2023)

-

New materials and designs for 2D-based infrared photodetectors

Nano Research (2023)

-

Small pixel infrared dual-color detector applying pixel-scale splitters integrated with infrared monochromatic detector

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2023)

-

Highly sensitive fast-response near-infrared photodetectors based on triple cation Sn-Pb perovskite for pulse oximetry system

Science China Materials (2023)