Abstract

Objective

To examine authorship gender distributions before and during COVID-19 in the Journal of Perinatology.

Study design

We collected data from the Journal of Perinatology website. The author gender was determined using Genderize.io or a systematic internet search. Our primary outcome was the difference between the number of published articles authored by women during the pandemic period (March 2020-May 2021, period two), compared with the preceding 15-month period (period one). We analyzed the data using chi-square tests.

Results

Publications increased from period one to two by 8.9%. There were slightly more female than male first (62%) and overall (53%) authors, but fewer last authors (43%) for the combined time periods. Female authorship distribution was not different between periods.

Conclusions

Though publications increased overall, authorship gender distribution did not change significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Women authors remain underrepresented overall and specifically as last author, considering the majority of neonatologists are women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gender disparities have been well-documented in many facets of medical careers, including in scholarly work and career advancement [1,2,3]. Although the majority of the pediatric and maternal-fetal medicine physicians are women [4, 5], women physicians are underrepresented as authors and editors across pediatric journals [4, 6,7,8]. Women physicians also receive fewer external grants than men, which may hinder their research output [9]. Women physicians are promoted more slowly and hold fewer leadership positions, compared to men [3, 10]. Some leadership positions may be granted to physicians with higher scholarly productivity [11]; thus, an imbalance in authorship may contribute to the unequal gender distribution of leadership roles. Domestic responsibilities that compete with academic work may also promote gender disparities. Women physicians report increased responsibility and more time spent on childcare, household obligations, and supporting family life than men [12, 13]. Women neonatologists are more likely than men to have a significant other who works full time and have younger children at home, leading them to bear a larger portion of domestic duties while working full time [11, 14]. The uneven distribution of domestic obligations may hinder their professional engagement and factor into the gender disparities in scholarly productivity and career advancement [4].

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically altered many areas of work and home life and amplified existing gender inequities in academic medicine [15]. Scholarly production was directly impeded by several work impacts such as stalled research projects [16], but also through disruption of the work-life balance that disproportionately affected women [17]. Baseline gender disparities in homelife responsibilities were exacerbated, primarily due to childcare and home-schooling needs [14, 18, 19]. Many institutions failed to produce standards for managing paid work and caregiving responsibilities during the pandemic, though many institutions recommended taking leave from work to support caregiving needs [20]. Since the beginning of the pandemic, the gap in female-male authorship increased [21,22,23]. The Journal of Perinatology, the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine, noted an increase in manuscript submission since the beginning of the pandemic, but the gender distribution was unknown [24].

Authorship gender has not been studied in a dedicated neonatology journal. Our objective was to examine gender distributions of authorship in the Journal of Perinatology and how they may have changed since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. We hypothesized that women physician-scientists published disproportionately fewer manuscripts than men in the Journal of Perinatology, both at baseline and since the beginning of the pandemic.

Methods

Data collection

We obtained data from the publicly available Journal of Perinatology website, with issue postings from December 2018 through March 2022. We included original investigation articles (Articles, Quality Improvement) and commissioned articles (Editorials, Review Articles, Comments, and Perspectives); Journal Club, Brief Communication, and Correspondence article types were excluded. We collected the following variables: first and last author names, submission and publication date, country and institution of first author, article type, and if the article was listed as supported by funding. We determined the authors’ gender (female, male, nonbinary, or indeterminate) using Genderize.io to assess the author’s first name. When the probability for assigned gender was ≥0.95, we assigned that gender to the author. When the probability was <0.95, we applied a secondary method to assign gender. We performed an internet search for the author in the following order until we found the author: 1) institutional websites, 2) ResearchGate, LinkedIn, and Doximity, 3) general Google search. We assigned gender based on listed pronouns when available or by female or male appearance.

Analyses

Our primary outcome was the difference between the number of publications by women authors resulting from submissions during the pandemic period (March 2020–May 2021, period two), compared with the preceding 15-month period (December 2018–February 2020, period one). Publications were excluded from this analysis if they had either a first or last author with indeterminate or nonbinary gender or lacked the last author. Univariate analysis was conducted for descriptive statistics and chi-square tests were performed to test for differences. A p-value of < 0.05 was chosen as the statistical significance level. All analyses were performed with IBM SPSS, Version 28.0.1.0 (142, Armonk, NY, USA); code available upon request. The Institutional Review Board at the Stanley Manne Research Institute affiliated with Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital provided oversight for this work (#2021–4658) and waived the need for consent as it utilized publicly available data.

Results

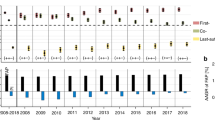

We identified 712 publications that were submitted between December 2018 and May 2021 and included 672 in our final cohort. Twelve publications had only one author (75% of these single-author publications had male authors) and 28 had authors names of undetermined binary gender (2.0% of the 1412 collected authors). Publication and author characteristics are presented in Table 1. Publications submitted during period one to two increased by 19.6%. There were slightly more female authors overall (52.8%), but fewer as last author (43.3%) for the combined time periods, compared with male authors. Forty-two percent of all publications were supported by funding, and 58% of those had female authors (authorship position and gender combinations presented Fig. 1, supplement). Regarding co-publishing between genders, the most common pairing had male, last authors, with female first authors, though single-gender-authored publications were more common than mixed gender (Fig. 2, supplement).

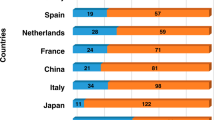

There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of female to male authors from period one to two in overall, first, or last authorship. The proportion of publications with non-United States first authors (n = 143) increased by 23.1% from period one to two and but the increase was not significant (p = 0.06). Of these 143 non-United States first authors, 60.8% were female overall and 54.5% and 64.8% were female in periods one and two, respectively. The proportion of invited articles increased by 50% from period one to two (p = 0.03). Of the 208 first and last authors of invited articles, 41.8% were female overall and 36.5% and 44.8% in periods one and two, respectively.

Discussion

This analysis of gender distributions of authorship within the Journal of Perinatology demonstrates several key findings. First, publications increased during the pandemic period in the Journal of Perinatology. Second, the proportions of publications authored by male and female authors were similar between the time periods, indicating distributions in gender authorship for this journal did not change significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Third, though there were more female than male authors overall and in the first position, fewer served as authors in the last position and for invited articles. As 71% of neonatologists board-certified in 2020, 56% overall, and >70% of incoming fellows for the last ten years are women [4], women are underrepresented as authors and especially as last authors and for invited articles in the Journal of Perinatology.

These trends spark curiosity surrounding academic productivity during the early COVID-19 pandemic. The increased publication trend during this pandemic period is noteworthy, mirrored the 36% increase in all Journal of Perinatology submissions between study periods[24], and was reported similarly by other journals [21,22,23]. This finding may be reflective of work prior to the pandemic as manuscript preparation is typically the culmination of months to years of preceding research. This effect, however, also may be attributed to opportunities the pandemic provided to conduct research and produce scholarly output. The COVID-19 pandemic presented a novel disease crucial for researchers to study and demanded increased publications to educate the field on its perinatal impact. Some researchers may have had differential time to spend writing manuscripts due to workplace (e.g., less time commuting and attending meetings) and societal (e.g., less availability of leisure activities) shutdowns. However, many reports cite significant negative pandemic impacts on both professional responsibilities and personal obligations that interfere with work; concerningly, these reports show greater negative effects on women [14, 17,18,19, 25]. Though we found no change in the gender proportions of authorship between pre-pandemic and pandemic periods for the Journal of Perinatology, the literature on this topic shows mixed results [21,22,23, 26,27,28]. These trends warrant attention as the pandemic wears on and its true impact on academic work remains to be seen.

Though the number of women serving as last authors did increase between time periods, this finding was not significant and women remain underrepresented; other studies have similarly documented underrepresentation of women as last authors [7, 27]. The increased number of invited articles from period one to two may be due to strategic efforts by editorial staff of the Journal of Perinatology unrelated to the pandemic [24]. Though reassuring to see the proportion of women authors as invited authors also increased, women still remain underrepresented, a finding also demonstrated in an evaluation of over 2500 journals [29]. Which author was the invited author(s) was not available from our data collection, precluding a deeper interpretation of this gender distribution. Our results raise significant concerns as women are underrepresented in authorship at baseline and scholarly productivity holds critical influence on career advancement in academic medicine [9, 23, 30].

This study was limited by the information included on the Journal of Perinatology website. We were unable to determine the authors’ professions and likely included disciplines beyond that of neonatologists (e.g., students, nurses, statisticians). The authors that were funded to support the publications were not stated, limiting this gender-based analysis. We analyzed the country of first author, though the full authorship team may be from the same, different, or multiple countries. We elected to only study first and last authors, as these typically hold the strongest contributions and responsibilities for a manuscript, though inclusion of middle authorship may show different results. Other analyses of authorship, such as by race or career level, were not feasible due to the availability of website data. Analysis of rejected manuscripts beyond only accepted submissions would have provided a more robust picture of all submissions, would have served as a better proxy for academic productivity during the pandemic, and permitted the examination of gender differences in manuscript acceptance rates but this data was not available. These latter points remain important areas of future studies. Finally, a misclassification of author’s gender with our approach is possible.

We believe our field can make changes to address gender differences in authorship. Individuals can be mindful of gender biases during mentorship, scholarly work, and selection of co-authors for manuscripts. Publishers can take steps to increase transparency and accessibility of gender data. They can collect data on gender and career level with submissions, review such data annually, and report these analyses via dashboards on their websites. To reduce potential implicit gender biases in the review process, they can provide reviewer support and education on article analysis and review strategies. Editorial staff can host workshops or webinars and post these recorded resources online. To encourage balanced gender distributions for invited articles, journals can prospectively track gender with invitation.

Further exploration of gender differences in authorship and the longitudinal impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the neonatal workforce is needed. Our analysis of gender distribution of authorship in the Journal of Perinatology suggests that increased efforts will be key to promote gender equity in academic productivity and career advancement within the field of neonatology.

References

Joseph MM, Ahasic AM, Clark J, Templeton K. State of women in medicine: history, challenges, and the benefits of a diverse workforce. Pediatrics. 2021;148:e2021051440C.

Spector ND, Asante PA, Marcelin JR, Poorman JA, Larson AR, Salles A, et al. Women in pediatrics: progress, barriers, and opportunities for equity, diversity, and inclusion. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20192149.

2018–2019 The State of Women in Academic Medicine: Exploring Pathways to Equity [Internet]. AAMC. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/data/2018-2019-state-women-academic-medicine-exploring-pathways-equity. Accessed 17 Jun 2022.

General Information on All Certified Diplomates | The American Board of Pediatrics [Internet]. 2022. https://www.abp.org/content/general-information-all-certified-diplomates. Accessed 13 Jun 2022.

Mei JY, Negi M, Han CS, Rao R, Krakow D, Afshar Y. Gender representation of speakers at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine postgraduate courses: a 20-year review. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100131.

Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Stewart A, Sambuco D, DeCastro R, Ubel PA. Gender differences in the salaries of physician researchers. JAMA. 2012;307:2410–7.

Puri K, First LR, Kemper AR. Trends in gender distribution among authors of research studies in pediatrics: 2015–2019. Pediatrics. 2021;147:e2020040873.

Williams WA, Garvey KL, Goodman DM, Lauderdale DS, Ross LF. The role of gender in publication in The Journal of Pediatrics 2015-2016: equal reviews, unequal opportunities. J Pediatr. 2018;200:254.

Oliveira DFM, Ma Y, Woodruff TK, Uzzi B. Comparison of National Institutes of Health grant amounts to first-time male and female principal investigators. JAMA. 2019;321:898–900.

Reed DA, Enders F, Lindor R, McClees M, Lindor KD. Gender differences in academic productivity and leadership appointments of physicians throughout academic careers. Acad Med. 2011;86:43–7.

Horowitz E, Randis TM, Samnaliev M, Savich R. Equity for women in medicine-neonatologists identify issues. J Perinatol J Calif Perinat Assoc. 2021;41:435–44.

Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, Stewart A, Ubel P, Jagsi R. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:344–53.

Eloy JA, Svider PF, Cherla DV, Diaz L, Kovalerchik O, Mauro KM, et al. Gender disparities in research productivity among 9952 academic physicians. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:1865–75.

Machut KZ, Kushnir A, Oji-Mmuo CN, Kataria-Hale J, Lingappan K, Kwon S, et al. Effect of Coronavirus Disease-2019 on the workload of neonatologists. J Pediatr. 2022;242:145.

Brubaker L. Women physicians and the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324:835–6.

Myers KR, Tham WY, Yin Y, Cohodes N, Thursby JG, Thursby MC, et al. Unequal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientists. Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4:880–3.

Dillon EC, Stults CD, Deng S, Martinez M, Szwerinski N, Koenig PT, et al. Women, younger clinicians’, and caregivers’ experiences of burnout and well-being during COVID-19 in a US healthcare system. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37:145–53.

Ferns SJ, Gautam S, Hudak ML. COVID-19 and gender disparities in pediatric cardiologists with dependent care responsibilities. Am J Cardiol. 2021;147:137–42.

Matulevicius SA, Kho KA, Reisch J, Yin H. Academic medicine faculty perceptions of work-life balance before and since the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. Netw Open. 2021;4:e2113539.

Nash M, Churchill B. Caring during COVID-19: a gendered analysis of Australian university responses to managing remote working and caring responsibilities. Gend Work Organ. 2020;27:833–46.

Williams WA, Li A, Goodman DM, Ross LF. Impact of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 pandemic on authorship gender in The Journal of Pediatrics: disproportionate productivity by international male researchers. J Pediatr. 2021;1:50–4.

Gershengorn HB, Vranas KC, Ouyang D, Cheng S, Rogers AJ, Schweiger L, et al. Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on author gender and manuscript acceptance rates among pulmonary and critical care journals. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202203-277OC. Epub ahead of print.

Wright KM, Wheat S, Clements DS, Edberg D. COVID-19 and gender differences in family medicine scholarship. Ann Fam Med. 2022;20:32–4.

Gallagher P. Gallagher PG. Personal communication, 2021–2022.

Staniscuaski F, Kmetzsch L, Soletti RC, Reichert F, Zandonà E, Ludwig ZMC, et al. Gender, race and parenthood impact academic productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic: from survey to action. Front Psychol. 2021;12:663252.

Wehner MR, Li Y, Nead KT. Comparison of the proportions of female and male corresponding authors in preprint research repositories before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2020335.

Fishman M, Williams WA, Goodman DM, Ross LF. Gender differences in the authorship of original research in pediatric journals, 2001-2016. J Pediatr. 2017;191:244.

Pinho-Gomes AC, Peters S, Thompson K, Hockham C, Ripullone K, Woodward M, et al. Where are the women? Gender inequalities in COVID-19 research authorship. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e002922.

Thomas EG, Jayabalasingham B, Collins T, Geertzen J, Bui C, Dominici F. Gender disparities in invited commentary authorship in 2459 medical journals. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1913682.

Silver JK, Poorman JA, Reilly JM, Spector ND, Goldstein R, Zafonte RD. Assessment of women physicians among authors of perspective-type articles published in high-impact pediatric journals. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:e180802.

Funding

This study was supported by a 2021 American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine Strategic Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design (LG, CD, RS, PG, KM), data collection (LG, KM), analyses (LB), first manuscript draft (LG), all authors revised the manuscript critically for substantive content and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gadek, L., Dammann, C., Savich, R. et al. Gender analysis of Journal of Perinatology authorship during COVID-19. J Perinatol 43, 518–522 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-022-01551-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-022-01551-x