Abstract

Objective

To explore fathers’ experiences of support following neonatal death, including the availability and perceived adequacy of support, barriers and facilitators to support and desired support.

Study design

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with ten Australian fathers who had experienced the death of a baby in the neonatal period at least 6 months previously. Data were analysed using thematic analysis.

Results

Two overarching themes were identified: From hospital to home: Continuity of care and Self and community barriers to support. Fathers who could access the support they required found this to be beneficial. Overall, however, supports were perceived as inadequate in variety and availability, with more follow-up support from the hospital desired. Fathers highlighted limited opportunities to form emotional connections with others and a strong desire to talk about their baby.

Conclusion

Healthcare professionals and support organisations can more effectively assist fathers by increasing the variety of supports available and facilitating follow-up or referrals after hospital discharge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The death of a baby in the neonatal period, defined in Australia as the death of a baby within the first 28 days after birth [1], is a usually unexpected pregnancy outcome occurring in ~2.5 of every 1000 pregnancies [2]. Research on the impact of gestational age or age of the baby on the intensity of parents grief are mixed, with literature emphasising the individualised nature of grief after the loss of a baby [3, 4]. Research suggests that there are numerous factors that impact the nature of parents grief, with neonatal death resulting in adverse impacts on parents’ physical and psychological wellbeing [5,6,7]. However, very few studies have focused on parents’ support needs following neonatal death, especially fathers’ needs [8], leaving a significant gap in knowledge concerning how to best support fathers in the event of neonatal death. Therefore, we aimed to explore Australian fathers’ support experiences after the death of their baby in the neonatal period.

Background and previous literature

When parents experience the death of a baby in the neonatal period, they may desire support from formal and informal sources, including tangible, informational, and emotional support. Within the hospital setting, mixed experiences have been reported following neonatal death, with most research focussing on mothers rather than fathers. For example, Redshaw and Henderson’s quantitative study of 249 mothers [9] found that limited private facilities were available, with some mothers receiving care in a postnatal ward alongside mothers with live babies. Often, there were minimal opportunities for fathers to discuss concerns privately with neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) staff [10] with no space for fathers to stay in the hospital overnight [9, 11]. In terms of information provision, results of studies have varied, with some mothers conveying positive experiences [9] and others reporting feeling disempowered due to a lack of accurate and useful information [11]. Overall, research into desired and required support in the hospital setting following neonatal death has highlighted a need for shared decision-making between healthcare professionals and parents [12].

There are often limited formal support options for parents after neonatal death and pregnancy loss, with primary supports including support groups and individual counselling [13,14,15]. Mothers have highlighted the importance of connecting with other parents who have experienced neonatal death to form an emotional connection and feel understood [16]. Peer support, particularly for parents in the NICU, can offer a shared experience in which parents can relate to each other and provide each other with comfort [13]. A qualitative study into a fathers’ support group within the NICU found that fathers may also benefit from peer support, as observing men in a similar situation and talking about coping strategies helps to give fathers a comparative norm [17]. However, research on men’s grief has suggested that some fathers may be reluctant to openly share their feelings in organised support groups [18].

Previous research regarding informal supports suggests that information or emotional support from family and friends is an important factor in coping after pregnancy loss or neonatal death [19]. For example, in one qualitative study, mothers discussed the importance of others acknowledging their baby’s life after neonatal death [16]. However, bereaved parents’ friends and family may feel unsure about how to best provide support, particularly for pregnancy loss and neonatal death, which continue to have an absence of norms and rituals concerning grief [20].

In an effort to improve care for parents after stillbirth and neonatal death, the Stillbirth Centre of Research Excellence (Stillbirth CRE) and the Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand (PSANZ) have recently updated guidelines to inform quality bereavement care practices [21]. These guidelines encompass four overarching care goals: good communication, shared decision making, recognition of parenthood and effective support. These goals are mirrored in neonatal death care guidelines internationally; in Ireland, Canada and the UK [22,23,24]. Practical recommendations from PSANZ/Stillbirth CRE for hospitals include a collaborative decision-making approach and facilitating parents to bond with their baby, through memory-making activities for example. Once discharged from the hospital, it is recommended that parents have access to 24-h follow-up support, written information about ongoing bereavement support services, and a hospital review meeting within 12 weeks of their baby’s death. While an excellent resource, the PSANZ/Stillbirth CRE guidelines focus predominately on supporting mothers or both parents together. The guidelines acknowledge that healthcare professionals should include fathers in all communication regarding their baby, but no bereavement support guidelines are specifically for fathers. Given research to suggest men and women may grieve differently following neonatal death [18, 25, 26] and a lack of specific recommendations relating to support for fathers, there is a need to understand father’s experiences of support and build on existing care guidelines.

We aimed to explore fathers’ support experiences following neonatal death through the following research questions: (1) What supports do fathers perceive are available to them following neonatal death, and are these considered adequate? and (2) What are some of the barriers and facilitators that fathers experience in accessing supports, and what future support options do they desire?

Subjects and methods

Study design

This study formed part of a larger research programme exploring Australian men’s grief and support experiences following pregnancy loss or neonatal death (other results published elsewhere [25]). As part of this more extensive programme, participants completed an online survey and indicated if they wished to participate in a follow-up interview. Participants who indicated such interest and had experienced a neonatal death were contacted for participation in the current study (N = 14).

Study sample and setting

Interviews were conducted with men across Australia between May and July 2020. Men who had experienced a neonatal death and expressed interest in a follow-up interview were contacted via the email address they provided in the survey. The neonatal death could have occurred at any time within the first 28 days since birth, but must have occurred at least 6 months before the interview, to minimise distress for fathers recently bereaved. Ten of the original 14 men (71%) responded to the invitation to participate and informed consent was obtained. The University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics Committee approved the research. The first author conducted interviews via telephone or Zoom due to participants’ geographic location and COVID-19 restrictions. Another researcher, a clinical and health psychologist, was available if a father became significantly distressed during his interview.

Given the exploratory nature of the research, interviews took a semi-structured approach with open-ended questioning. Interview questions were developed based on previous pregnancy loss studies [26,27,28], including the findings of the larger research programme [25]. A pilot interview assessed the proposed interview schedules’ suitability: no changes were required. Example interview questions included: “can you tell me about your experiences in the neonatal intensive care unit?” and “were you offered information on men’s grief or the supports that may be available to you?”. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim using an orthographic method [29]. Each participant was allocated a pseudonym to maintain confidentiality, and all identifying features were removed from the transcripts.

Following Tracy’s [30] criteria for robust qualitative research, an audit trail was used and participants could review their transcript and a theme overview to allow for member reflections. Three participants responded; two indicated agreement with the theme overview, and one provided additional feedback (specifically highlighting the difference between neonatal death and other pregnancy loss types and emphasising the need for specialised support services based on the type of loss).

It is important to engage in self-reflexivity when undertaking qualitative research [30]. The first author does not have children and has no experience of pregnancy loss or neonatal death. Therefore, participants may have felt that the interviewer would be unable to directly relate to their experiences, which may have influenced participants’ willingness to speak openly. However, multiple participants expressed a strong desire to discuss their neonatal death experiences and verbalised their appreciation for research focusing on this under-represented area. Most fathers expressed a hope that sharing their experience would contribute to better support for men in the future. The second and fifth authors do not have children, while the third and fourth authors are women with children. The fourth author has experience of pregnancy loss, and the fifth author has experience of pregnancy loss and neonatal death (great nephew). None of the authors are clinical neonatal professionals.

Data analysis

The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) checklist [31] guided the reporting of this research. This study was informed by a realist epistemology, whereby meaning was not applied beyond the participants’ interview data [29]. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data. After the interviews were transcribed, six steps to comprehensive thematic analysis [29] were undertaken. An inductive approach was used to identify themes from the data, guided by the research questions. At each step of the analysis, codes and themes were discussed and refined through discussions between the authors to ensure the trustworthiness of the themes. All authors agreed on the final themes.

Results

Interviews ranged between 45 and 97 min in length (M = 61 min). Participants were aged between 31 and 42 years (M = 35 years) at the time of the interview, and time since loss was between one and 12 years ago (see Table 1). The age of the baby at the time of death ranged from 30 min to 27 days. For brevity, the term “baby” will be used, however we wish to explicitly acknowledge that one father lost twins in the neonatal period. All participants were in a relationship with the mother of their baby at the time of the interview.

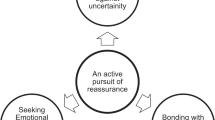

Thematic analysis led to two overarching themes: “From hospital to home: continuity of care” and “Self and community barriers to support”. Each theme also includes three subthemes (see Fig. 1).

From hospital to home: continuity of care

Hospital support experiences are critical to fathers’ support needs

Most fathers reported positive experiences of support within the NICU and hospital. For example, Nathan praised the NICU nurses that cared for his baby, saying: “The NICU staff, the nursing staff particularly, were brilliant”. Most fathers described clear, sensitive communication about their baby’s medical condition from healthcare professionals:

“Everyone was amazing and spoke clearly and, um, presented our options in the most professional manner they could.” (Ben)

All fathers described spending time with their baby at the point of death, and many highlighted that healthcare professionals encouraged bonding with their baby. This was also the case for babies who had no chance of survival who were not admitted to the NICU. Some fathers were also provided with private time with their baby before their death, with one father describing efforts from the NICU nurses to ensure his baby’s wellbeing was not compromised:

“…we hadn’t actually had the chance to, you know, put him on our lap and sit with him and so when [my wife] asked to do that, they had like six nurses come in and work together to move all the machinery and [baby] around to make sure that everything stayed connected and nothing got broken. […] they’re very caring people.” (Harrison)

Many fathers reported feeling included in the NICU and the hospital. Sam described that both he and his wife “were included and basically put at the same level”. However, some fathers noted that there was a clear focus on the mother of their baby. There were often minimal practical facilities and space to accommodate fathers in the hospital, despite their baby’s severe medical complications and limited chance of survival. This was reflected by Cameron, who stayed at the hospital for the 3 days that his baby lived:

“So my wife had a private room um and it had like a bench, it was almost single bed length, not quite single bed width, but yeah they provided blankets and stuff I just had to like clean them up, fold them up and just re-use them. They wouldn’t replace them and that was fine. The first couple of nights I just slept in the, um, well one of the nights I slept in the family room, in the NICU, for like an hour and I was like the only one in there.”

While Cameron was not provided with a place to sleep in the hospital, he noted that he and his family were given privacy when sensitive medical information was delivered, and were moved to a quieter ward after his son’s death:

“…when he died, they moved everyone into a separate room where it wasn’t as busy […] They put a blue butterfly on the door [as a] signal [of neonatal death]. The others on the street don’t know what it is, but all the midwives and nurses and stuff, doctors, all know what that means and that you’ve lost a child.”

Other fathers echoed that these subtle actions by the hospital system were helpful in acknowledging their grief.

“Like a number in the system”: inconsistencies with discharge from the hospital and follow-up supports

While fathers mostly felt that hospital services before their baby’s death and in the NICU were sufficient, there were inconsistencies in experiences after their baby died and following discharge from the hospital. A focus on the mother also extended to emotional supports provided to parents after their baby’s death, with some fathers reporting that they were unable to access hospital bereavement services as they were not officially recognised as a patient in the hospital. In line with recommendations from PSANZ/Stillbirth CRE [21], all fathers received information about supports available after discharge in the form of booklets or pamphlets. Two fathers, whose losses occurred a decade apart (2 and 12 years ago), received a pamphlet about supports specifically tailored for fathers. No other father-specific supports were reported. Some fathers described this provision of information to be the only support offered by the hospital at the point of discharge:

“…all of the support we were given was basically, booklets and things like that and with information to the places like [community support organisations] and things like that but no direct contact.” (Sam)

In addition to limited information about male-specific supports, Harrison indicated that he found it challenging to obtain additional support from the hospital:

“…I remember they definitely offered their services to us to help, but I also remember after that they were really hard to get hold of. The social worker we had was um ((pauses)) probably a very busy person, but trying to get hold of her to book in meetings or just have a chat, seemed really difficult.”

Most fathers did not receive a follow-up telephone call from the hospital. Ben described receiving no contact despite explicitly being told that the assigned social worker would call him:

“…the social worker that we were seeing at the hospital had said that she would give us a call a week or two weeks after we returned home and, we didn’t receive a call. […] there was um, no other form of contact from the social worker that we’re aware of either.”

Several fathers were offered a review meeting with a healthcare professional in the hospital. These meetings were to enable parents to discuss their baby’s medical complications and their wellbeing. However, the review meetings focused on the mother, and some fathers perceived that they were overlooked:

“…there was a review session with the hospital as well, there was a definite focus on [my wife] rather than myself as the dad […] that may also have been because I was a little bit closed-off as well, but they would more often talk to her about what was going on and uh sort of like what feelings were happening for her rather than specifically approaching me about them.” (Nathan)

Most fathers desired male-specific supports, but felt that information provided about these supports was inadequate or not tailored to their needs. Bill, who strongly desired follow-up phone calls from the hospital, likened this lack of direct follow-up support to being treated “like a number in the system”, indicating a lack of tailored and specialised services for fathers.

Referral/continuity of services: the key facilitator to engagement in support options

Engagement with formal supports was limited, however some fathers reported positive experiences and successful engagement in formal support options. Harrison, who engaged with several bereavement support providers, described being referred to these services before discharge from the hospital:

“…the social worker at the hospital, she got us onto um organisations like [organisation] and [organisation] and uh I think [organisation] is the other one that deal with sort of helping people get through the loss of a child. We connected pretty well with [organisation] and we went to support groups for their infant loss help and we still have like ongoing counselling one on one with one of their counsellors every month or so…”

Another father experienced continued care from the hospital, as the bereavement counsellor supporting him in the hospital setting continued to support him after discharge:

“When [baby] was in NICU we had the bereavement counsellor […] she was very good, we continued seeing her for a few months and then she went on leave […] we’d meet her privately and just have a coffee or a chat outside of the hospital” (Cameron)

Further analysis suggested that formal support, particularly individual counselling, was more likely to be used by fathers if they had accessed it previously. For example, Adam actively sought support from a psychologist he had seen previously:

“He’s a person that I did see probably ten years before that. I had a lot of things happen in my career that I felt very hard to deal with, I lost a whole career because of a medical issue, so he helped me in a short period of time just, reconcile with that a little bit and provide a bit of direction. So I was quite comfortable knowing I was going to a person who I knew and trusted so that made it a bit easier.”

Overall, men identified that follow-up supports from the hospital were minimal and inconsistent, leading to a lack of continuity of care. However, in some cases, engagement in formal support options was facilitated by adequate referral to services by the hospital or prior positive experiences with support.

Self and community barriers to support

Informal supports: social recognition and acknowledgement

Fathers described the importance of talking about their baby’s birth and death, however expressed that family and friends were often unwilling to engage in these discussions. Some fathers shared a belief that their family and friends may have been unaware of appropriate ways to respond to a parent who has experienced neonatal death. Harrison explained:

“I think a lot of people were too scared to have said anything […] I mean what do you say, there’s not really any words that can make it better, so I suppose that’s just people trying to protect themselves as well as protect you.”

The nature of these experiences did not seem to vary substantially according to the time since fathers’ losses had occurred, highlighted in descriptions from Paul, who experienced a neonatal death 10 years ago:

“…all our friends disappeared. People just didn’t call anymore, even siblings, no one would bring it up. It’s all we wanted to talk about, it’s all we cared about, is our baby and it died, but no one would talk about it because they didn’t want to upset us.”

As social recognition and acknowledgement were unavailable, with referral to services by the hospital reported above, Harrison engaged with a support group. Harrison describes positive experiences with the support group, where he received acknowledgement for the life and death of his baby:

“Support groups were good they were very close and quiet and people just sharing stories and pictures […] it was nice just to go somewhere like once a month and not have to worry about getting upset or saying the wrong thing and people just getting it.”

Overall, most fathers expressed that they did not feel that those around them recognised their loss or could provide adequate informal support and emphasised the need to acknowledge their baby’s life.

Masculine norms can impede engagement in support for fathers

Fathers in this study described focusing on practical tasks and being the supporter for their female partner and family following neonatal death. This focus was considered a barrier to support for some fathers, who found it challenging to balance expressing their needs while simultaneously being “strong” and attending to responsibilities. In contrast to Harrison’s support group experience above, when Adam was offered to attend a NICU-connected support group while his baby was in the NICU, he chose not to engage due to fear of openly expressing his emotion:

“… I didn’t go. Um I think there’s probably two parts to it, one I was you know, it was a lot to deal with and that was just another thing I didn’t want to have to deal with, but there also is a lot of fear in that too. I’m going to have to go in there and address everything that I’m feeling about it […] I’m better off just, staying focused on the task at hand and doing it that way. Looking back on it I probably should’ve done that, but, you know, it’s optional they don’t make you do it.”

In line with this, Bill described hesitancy to actively seek support as he was a “stereotypical bloke” who “wouldn’t be willing to ring this support group”. Despite a strong desire for both professional and peer support options explicitly aimed at fathers, the availability of such support was limited for the fathers in this study. Cameron attributed this limited availability of male-specific supports to a lack of engagement/interest by other fathers, as a result of masculine norms:

“…they had like a father’s group thing but the take up on that, like there was supposed to be like a coffee thing that I was going to go to but then they cancelled it because there was only two people that said yes, and they just, like I don’t know - don’t know if it’s a cultural thing [or] like a masculinity thing that you know, we’ll just grin and bear it or they’ve got other kids other responsibilities to work or whatever.”

Similarly, Sam, who experienced a neonatal death over a decade ago, was unable to find the emotional connection he was seeking when his baby died. Sam went on to volunteer for a pregnancy loss/neonatal death support organisation attempting to provide fathers with an opportunity to connect with another father. However, Sam found that the demand for men’s services was low; he did not receive a single call:

“…I actually ended up uh later on uh, training at [organisation] as a volunteer myself but was never I was called up once in the whole time that I volunteered there, so I don’t think […] a lot of men [engage].”

Overall, the support options desired by fathers in this study varied, with some fathers unable to access the father-specific emotional supports that they were seeking, and others choosing not to engage in emotional supports despite these options being available to them.

Support options must be varied to meet fathers’ needs

Although fathers described limited uptake of father-specific supports, the fathers in this study also emphasised that father-specific supports were limited in nature and that supports were focused primarily on mothers. All fathers indicated that the focus on mothers was somewhat warranted, as the mothers had experienced the physical process of pregnancy and birth. Despite this, most fathers emphasised that they still required individualised bereavement support, separate and different to the support provided to the mother of the baby. For example, Paul described how he and his wife’s experiences differed:

“…it affected my wife straight away and it’s obviously because she had that physical connection with him um being in her and going through the birth, whereas I was just - I almost distracted myself by focusing on some of the medical and technical things that happened and I think I was affected emotionally, in a more slow and over a longer period of time, so I think it’s the different kind of support.”

Overall, the support options currently available to men were considered insufficient, with greater variability and availability desired. Adam explained that others kept trying to push him towards support groups when that type of support did not appeal to him:

“…I think everyone tries to push you into these group things […] I don’t know maybe they are successful, I don’t know but for me it was just not something that, you know, I’m not too sure I would um, recommend how hard they push you into that and I think that, if they could offer different forms, it seems to be that that’s the only way, it’s like hey there’s a men’s group go over there. That seems to be the answer once you leave the hospital.”

Several fathers also highlighted a need for support options that allowed expression of emotion from men, as they “need to feel the grief and anger and whatever else that [they] want to feel, otherwise it can overtake [them]” (Ben). Although some fathers have reported that they did not engage in emotional supports, others expressed a desire to connect with another father to make sense of their experience. This desire aligned with the limited social recognition fathers experienced regarding their loss. Harrison, who attended a formal support group, described the need for male-specific supports throughout his experience:

“…the support groups are really good but you know, sitting in there when you’re the only dad and it’s full of you know eight or nine mums it’s hard [because] mum and dads have different connections […] I think if there was a dads group running, I think that would’ve helped a little bit more, at least just to start knowing that everything I was feeling was normal for the situation that I was in, because a lot of the time you doubt yourself like am I allowed to laugh at these jokes or you know am I allowed to smile today.”

Finally, Paul found that some formal supports were not specialised enough regarding neonatal death. For example, he suggested that combining supports with other pregnancy losses such as miscarriage made it more difficult for him to relate to other parents involved:

“…we always hated it when people would compare a miscarriage experience to a neonatal death, so whenever we kind of talked about our experience and somebody was talking about miscarriage we felt that’s not even in the same realm […] we kind of [felt as] though they’re not the same thing and you can’t – the services need to be different because there’s different needs.”

Overall, many fathers highlighted masculine norms and limited access to male-specific supports as barriers to support. Hospital referrals to support options and adequate continuity of care were considered facilitators to accessing support. The available support options were reported to focus primarily on the bereaved mother, and fathers expressed a need for a greater variety, as some were unable to access the type of support they desired. Several fathers expressed that peer support from another father would have been beneficial.

Discussion

The fathers in our study reported mostly positive experiences within the hospital and NICU setting; however, they described minimal follow-up support from hospital staff. Where support options were familiar to fathers or referral to services was facilitated before discharge from the hospital, these acted as facilitators to support engagement. Barriers to engagement included masculine norms, male “supporter” role expectations, and limited availability and variety of support options. These experiences are consistent with fathers’ support experiences reflected in the wider pregnancy loss literature [25, 32]. Overall, fathers in our study expressed a desire for greater availability of male-specific support options, including peer and professional support facilitated by males. Our findings point to a clear need to develop and fund evidence-based support options that are best suited for men who have experienced neonatal death.

In sharing their support experiences, fathers in our study highlighted the importance of specialised support for fathers who have experienced the death of a baby in the neonatal period. Neonatal death presents unique challenges compared to other pregnancy losses due to the emotional toll of having a baby admitted to the NICU, with different considerations regarding the baby’s medical care and potential decisions regarding withdrawal of life support [33]. Guidelines that combine general recommendations for both stillbirth and neonatal death may overlook this difference. Despite this, all fathers in our study reported positive experiences of support within the hospital setting, including being provided with privacy, clear explanations of medical complications, and sensitive delivery of information. However, while most fathers reported feeling included by hospital and NICU staff, limited facilities and space for fathers to stay in hospital were also reported. This issue is consistent with literature that examines fathers’ experiences in the NICU [11].

Mirroring pregnancy loss research [15, 32], inconsistencies in support were most commonly reported regarding follow-up services and the provision of information upon hospital discharge. Fathers across our sample described that most supports occurred before hospital discharge, with minimal supports provided to fathers outside the hospital setting. As per the PSANZ/Stillbirth CRE guidelines [21], fathers were provided with written information on support options; however, few of these supports were specific to fathers. Importantly, while fathers noted clear gaps in bereavement care and support, all fathers also reported positive experiences within the NICU, with many reflecting on positive support experiences with their in-hospital social worker or counsellor. Positive NICU and hospital staff experiences have been reflected in a variety of literature [14, 34, 35]. With this existing relationship, the in-hospital social worker or counsellor is well-positioned to facilitate referral to formal support options after hospital discharge and encourage engagement in those supports. The few fathers in our study who attended a support group also reported adequate facilitation of services by the hospital, emphasising the hospital’s opportunity to establish support options after neonatal death. Participants who desired greater emotional and practical support but did not engage in existing support options also highlighted the need for increased follow-up support and facilitation of referrals to community support services tailored to fathers.

We identified two main barriers to accessing support. First, cultural and societal norms concerning men—such as heterosexual men as supporters to their female partners—that exist in many western cultures [36, 37] were consistently reported by the fathers in our study. Fathers in our study experienced minimisation of their experience and lack of validation from healthcare professionals, friends and family, consistent with research focusing on men’s experiences after a child’s death [38, 39]. While some fathers reported supportive and helpful experiences with family and friends, comments from others that minimised fathers’ emotions were hurtful.

In addition, most fathers reflected that existing supports were limited in variety and availability, and highlighted the importance of diverse support options. Suggestions for useful support options varied and, in some cases, did not align with responses from other fathers. Across our sample, fathers described a need for peer support opportunities with other fathers, follow-up telephone calls to discuss the emotional toll of their experience and individualised bereavement support for fathers separate to supports provided to the mother of the baby. While support groups and counselling were available, some fathers reported that the emotional connection they were seeking was unavailable due to a lack of facilitated connections between bereaved fathers. Peer support from other bereaved parents is essential when parents face limited social recognition and disenfranchised grief, as reflected in previous neonatal death research [17, 18]. The PSANZ/Stillbirth CRE guidelines highlight the importance of adequate communication with fathers and giving them ways to express their support needs, as their expressions of grief may differ from those of mothers [21].

Limitations and future research

While we have highlighted important aspects of fathers’ support needs for future revision of bereavement care guidelines, there is a need for research with fathers of more varied demographic criteria, including age, cultural background and marital status. The recruitment approach for participants for this study and self-selected nature of sampling is open to potential bias, as the fathers of our study may have been unique from fathers who were unaware of the study or those who chose not to participate. Additionally, although the majority of men reflected on losses within the last 5 years, this study relied on retrospective accounts of grief that may be open to recall bias and changes to health system/policy level supports, especially for losses that occurred up to 12 years ago. However, analyses did not indicate any significant differences between support experiences according to time since neonatal death. Our qualitative study also focused specifically on fathers’ experiences of support; it did not examine whether support would be most effectively delivered by the NICU team or other healthcare professionals external to the hospital. Future research may examine the most effective timing, provider and delivery (i.e., individual or parent) for fathers, as well as broadening inclusion to all fathers whose baby dies in the NICU rather than only those who die before 28 days.

Future research is also required to build upon the few existing studies (e.g., [39,40,41,]) that have sought to understand the support and bereavement care needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, and other gender or sexuality diverse (LGBTQIA+) parents who have experienced the death of a baby in the neonatal period. LGBTQIA+ parents may face additional challenges due to heteronormative values and the potential avoidance of formal peer supports due to fear of prejudice [40,41,42,43].

As this research occurred within the Australian context, it focuses on bereaved fathers’ experiences in a particular set of cultural norms and values. A disproportionate amount of existing research on pregnancy loss and neonatal death is situated within western contexts, with the experiences of fathers in other cultural contexts often overlooked [44]. The barriers and facilitators reported across the literature may not apply, and supports may differ in other cultural settings or for people from other cultural backgrounds [45, 46]. Future research in various contexts will assist in developing an understanding of supports that may benefit across cultures.

Due to the sensitive nature of neonatal death, studies in this area typically consist of small sample sizes and express difficulties in developing rigorous clinical trials [47]. Further research may build on the current findings by trialling and evaluating various male-specific services to determine best-practice support options for fathers after neonatal death.

Conclusions

Minimal literature about fathers’ experiences of neonatal death, and in particular support experiences, exists. This first Australian study to explore fathers’ experiences of support following neonatal death has highlighted the need for variety and availability of male-specific supports for fathers after neonatal death. Key policy and practice recommendations stemming from this paper include: the provision of greater recognition and facilities for fathers in the hospital setting; funding and resourcing for hospital follow-up support to provide continuity of care and facilitate the transition to community-based support services, and; the development of targeted support strategies and bereavement care programmes for men specifically, including peer support. In developing such supports, consideration should be given to masculine norms such as heterosexual men as supporters to their female partner and men as “tough” and “stoic”. Finally, reconnecting with previously engaged or existing formal supports should be encouraged. In conclusion, men whose baby died in the neonatal period currently face a substantial lack of varied and desired support options in Australia. There is a clear imperative for further research and the development/evaluation of support programmes to support this group of men.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Causes of Death, Australia, 2018. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2018.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Stillbirths and neonatal deaths in Australia 2017. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2020.

Hvidtjørn D, Prinds C, Bliddal M, Henriksen TB, Cacciatore J, O’Connor M. Life after the loss: protocol for a Danish longitudinal follow-up study unfolding life and grief after the death of a child during pregnancy from gestational week 14, during birth or in the first 4 weeks of life. BMJ Open. 2018;8:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024278.

Fernández Ordóñez E, Rengel Díaz C, Morales Gil IM, Labajos Manzanares MT. Post-traumatic stress and related symptoms in a gestation after a gestational loss: narrative review. Salud Ment. 2018;41:237–43. https://doi.org/10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2018.035.

Banerjee J, Kaur C, Ramaiah S, Roy R, Aladangady N. Factors influencing the uptake of neonatal bereavement support services—findings from two tertiary neonatal centres in the UK. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-016-0126-3.

Lang A, Fleiszer AR, Duhamel F, Sword W, Gilbert KR, Corsini-Munt S. Perinatal loss and parental grief: the challenge of ambiguity and disenfranchised grief. Omega Westport. 2011;63:183–96. https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.63.2.e.

Camacho Ávila M, Fernández Medina IM, Jiménez-López FR, Granero-Molina J, Hernández-Padilla JM, Hernández Sánchez E, et al. Parents’ experiences about support following stillbirth and neonatal death. Adv Neonatal Care. 2020;20:151–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0000000000000703.

Woodroffe I. Supporting bereaved families through neonatal death and beyond. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;18:99–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2012.10.010.

Redshaw M, Henderson J. Mothers’ experience of maternity and neonatal care when babies die: a quantitative study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208134.

Fisher D, Khashu M, Adama EA, Feeley N, Garfield CF, Ireland J, et al. Fathers in neonatal units: Improving infant health by supporting the baby-father bond and mother-father coparenting. J Neonatal Nurs. 2018;24:306–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnn.2018.08.007.

Serlachius A, Hames J, Juth V, Garton D, Rowley S, Petrie KJ. Parental experiences of family-centred care from admission to discharge in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;54:1227–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.14063.

Kendall A, Guo W. Evidence-based neonatal bereavement care. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev. 2008;8:131–5. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.nainr.2008.06.011.

Archibald S-J. What about fathers? A review of a fathers’ peer support group on a neonatal intensive care unit. J Neonatal Nurs. 2019;25:272–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnn.2019.05.003.

Harvey S, Snowdon C, Elbourne D. Effectiveness of bereavement interventions in neonatal intensive care: a review of the evidence. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;13:341–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2008.03.011.

Obst KL, Due C. Australian men’s experiences of support following pregnancy loss: a qualitative study. Midwifery. 2019;70:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2018.11.013.

Waugh A, Kiemle G, Slade P. Understanding mothers’ experiences of positive changes after neonatal death. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2018;9:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1528124.

Thomson-Salo F, Kuschel CA, Kamlin OF, Cuzzilla R. A fathers’ group in NICU: recognising and responding to paternal stress, utilising peer support. J Neonatal Nurs. 2017;23:294–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnn.2017.04.001.

Doka KJ, Martin TL. Grieving styles: gender and grief. Grief Matters Aust J Grief Bereave. 2011;14:42–5.

Lasker JN, Toedter LJ. Predicting outcomes after pregnancy loss: results from studies using the perinatal grief scale. Illn Crisis Loss. 2000;8:350–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/105413730000800402.

McCreight BS. A grief ignored: narratives of pregnancy loss from a male perspective. Socio Health Illn. 2004;26:326–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2004.00393.x.

Boyle F, Dell H, Middleton P, Flenady V. Clinical practice guideline for care around stillbirth and neonatal death: Section 3, Respectful and supportive perinatal care. 3rd ed. Australia: Stillbirth Centre of Research Excellence; 2019.

National standards for bereavement care following pregnancy loss and perinatal death. Ireland: Health Service Executive; 2019.

Neonatal death: full guidance document. United Kingdom: National Bereavement Care Pathway; 2020.

Henderson L, Davies D. Supporting and communicating with families experiencing a perinatal loss. Canada: Canadian Paediatric Society; 2020.

Obst KL, Due C, Oxlad M, Middleton P. Men’s grief following pregnancy loss and neonatal loss: a systematic review and emerging theoretical model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2677-9.

Kimble DL. Neontal death: a descriptive study of fathers’ experiences. Neonatal Netw. 1991;9:45–9.

Jones K, Robb M, Murphy S, Davies A. New understandings of fathers’ experiences of grief and loss following stillbirth and neonatal death: a scoping review. Midwifery. 2019;79:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2019.102531.

Smith LK, Dickens J, Bender Atik R, Bevan C, Fisher J, Hinton L. Parents’ experiences of care following the loss of a baby at the margins between miscarriage, stillbirth and neonatal death: a UK qualitative study. BJOG. Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;127:868–874. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16113.

Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. London: Sage Publications; 2013.

Tracy SJ. Qualitative quality: eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual Inq. 2010;16:837–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health. 2007;19:349–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

Cacciatore J, Erlandsson K, Rådestad I. Fatherhood and suffering: a qualitative exploration of Swedish men’s experiences of care after the death of a baby. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:664–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.10.014.

Fry JT, Henner N. Neonatal death in the emergency department: when end-of-life care is needed at the beginning of life. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2016;17:147–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpem.2016.04.001.

Hearn G, Clarkson G, Day M. The role of the NICU in father involvement, beliefs, and confidence: a follow-up qualitative study. Adv Neonatal Care. 2020;20:80–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0000000000000665. 2019/10/01 ed.

Ireland S, Ray RA, Larkins S, Woodward L. Perspectives of time: a qualitative study of the experiences of parents of critically ill newborns in the neonatal nursery in North Queensland interviewed several years after the admission. BMJ Open. 2019;9:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026344.

Addis ME, Mahalik JR. Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. Am Psychol. 2003;58:5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.5.

Bonnette S, Broom A. On grief, fathering and the male role in men’s accounts of stillbirth. J Socio. 2012;48:248–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783311413485.

Aho AL, Tarkka MT, Astedt-Kurki P, Kaunonen M. Fathers’ grief after the death of a child. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2006;27:647–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840600643008.

Aho AL, Tarkka M-T, Åstedt-Kurki P, Kaunonen M. Fathers’ experience of social support after the death of a child. Am J Mens Health. 2009;3:93–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988307302094.

Peel E. Pregnancy loss in lesbian and bisexual women: an online survey of experiences. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:721–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dep441.

Riggs DW, Pearce R, Pfeffer CA, Hines S, White FR, Ruspini E. Men, trans/masculine, and non-binary people’s experiences of pregnancy loss: an international qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03166-6.

Wojnar D. Miscarriage experiences of lesbian couples. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2007;52:479–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.03.015.

Shannon E, Wilkinson B. The ambiguity of perinatal loss: a dual-process approach to grief counselling. J Ment Health Couns. 2020;42:140–54. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.42.2.04.

Roberts L, Montgomery S, Ganesh G, Kaur HP, Singh R. Addressing stillbirth in India must include men. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2017;38. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2017.1294220.

Petrites AD, Mullan P, Spangenberg K, Gold KJ. You have no choice but to go on: How physicians and midwives in Ghana cope with high rates of perinatal death. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:1448–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-1943-y.

Shakespeare C, Merriel A, Bakhbakhi D, Baneszova R, Barnard K, Lynch M, et al. Parents’ and healthcare professionals’ experiences of care after stillbirth in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-summary. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;126. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15430.

Koopmans L, Wilson T, Cacciatore J, Flenady V. Support for mothers, fathers and families after perinatal death. Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000452.pub3.

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this research to Lucas, Caleb, Charlotte, Thomas, Tristan, Odin, Fianna, Saoirse, Charlie, James and Lucy, whose fathers’ stories are told here. We sincerely thank these fathers for their honest and raw accounts of their experiences and for openly sharing their stories.

Funding

KLO is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship and a Westpac Scholars Trust 2018 Future Leaders Scholarship. No funding body was involved in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MO, CD and KLO conceptualised the study. SA, MO, CD and KLO drafted the interview questions and ethics application. SA conducted and transcribed the interviews, conducted the initial data analysis and drafted the manuscript. MO, CD and KLO assisted with data analysis and agreed upon final themes derived. MO, CD, KLO and PM critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Azeez, S., Obst, K.L., Oxlad, M. et al. Australian fathers’ experiences of support following neonatal death: a need for better access to diverse support options. J Perinatol 41, 2722–2729 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01210-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01210-7