Abstract

Objective

To explore how the fathers experience their role as a support for their partner and the relationship with them during their preterm infant’s stay in the NICU.

Study design

Multi-method longitudinal study involving ethnographic observation, semi-structured interviews, self-report questionnaires, and clinical information. Twenty fathers of preterm infants hospitalized in a level-III-NICU were included. Data were analyzed using thematic continent analysis.

Results

Three main themes were identified: support for mother (subthemes: putting mother’s and infant’s needs first; hiding worries and negative emotions; counteracting the sense of guilt; fear that the mother would reject the child), mother’s care for the infant (subthemes: observing mother engaged in caregiving; mother has “something extra”), and couple relationship (subthemes: collaboration; bond).

Conclusion

Fathers supporting their partners during the stay in the NICU experience emotional distress and the need for being supported that often are hidden. This demands a great deal of emotional and physical energy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The preterm birth and subsequent admission of a child to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is a critical event for both mothers and fathers [1, 2], even in the absence of medical risk and injuries for the infant. Indeed, several studies have shown that parents of these infants experience high levels of psychological distress, with high fatigue, sleep disruption, and reduced general wellbeing [3,4,5]. During the prenatal and postpartum periods mothers’ and fathers’ emotional states have been found to be significantly correlated [6], and parental mental health affects self-efficacy [7] and influences the quality of both parent-infant interaction [8,9,10] and parent–infant attachment [11]. It also can harm the early neurobehavioural and socioemotional development of the infant [12].

Background

Over recent decades, neonatal health care systems have promoted the whole family’s wellbeing in a family-centered approach to NICU care [13]. This approach aims to involve parents in all aspects of their infant’s daily care. Consequent beneficial effects in the infants include higher average daily weight [14] and improved neurobehavioral profile [15]. In parents, O’Brian et al. [14], found lower mean anxiety and stress scores than those in the standard care group.

Although fathers’ and mothers’ experiences differ substantially [3, 16], most research projects and current support programs in infant prematurity focus mainly on infants and mothers. The few studies that have also focused on fathers have recognized their experience in the NICU [17, 18] and the crucial role they play in the infant’s psychological and neurodevelopment development [19, 20]. Even fewer studies have evaluated—and, to our knowledge, a limited number of studies have specifically focused on—fathers’ experiences of supporting and caring for their partner and/or fathers’ perceptions of the quality of the couple’s relationship during their preterm infant’s stay in the NICU. Some of these few studies have found that mothers get most of their psychological support from their partner [21, 22]. Regarding the couple relationship, an important concept is that of couple bond, i.e., mutual understanding of what partners provide and receive from each other [23]. A good couple bond is characterized by a reciprocal, not-hierarchical dependence that involves interdependence, personal enhancement, mutually supportive strength and value [24]. It reflects the personalities of the two partners, and their respective family histories and cultures, who may or not take advantage of the resources and repair the deficiencies in caretaking that each partner inevitably brings with him/her [24].

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to explore how the fathers view and experience (a) their role as a support for their partner, and (b) the relationship with their partner during their preterm infant’s stay in the NICU. A secondary aim was to assess whether different profiles (clusters) of the fathers’ partnership experiences could be identified from their narratives and whether these eventual profiles could be explained by any characteristics of the fathers and/or their partners. Identifying specific fathers’ and/or partners’ characteristics associated with different experiences might inform screening and early intervention strategies to support parents in NICU.

Methods

Design

This study used a multi-method approach and a mixed-method research design to provide a rich understanding of fathers’ experiences during their preterm infants’ hospitalization in a Level III NICU and develop a conceptual framework that could have clinical implications for healthcare professionals and services. The study included ethnographic work [25] in one NICU for 18 months (from September 2015 to March 2017), semi-structured interviews with fathers, and self-report questionnaires completed by both fathers and mothers. The researcher (first author) was a male psychologist–psychotherapists trained in infant observation and clinical psychological assessment, not associated with the hospital. The NICU staff introduced him as a psychologist and PhD student who was studying the impact of prematurity on infants and their parents. The mixed-method design was primarily qualitative with a quantitative component (see Data analysis). A protocol of the larger research project that includes this study was published [26]. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ) were followed in reporting this study (see Supplementary File 1).

Study setting

The study took place in a Level III NICU at’Borgo Roma’ University Hospital in Verona, northern Italy. In 2017 the unit was transferred to another University Hospital (“Borgo Trento”) in the same town. The unit had 20 beds, and each year it admitted approximately 450 neonates with medical and/or surgical diseases. Most of the neonates hospitalized were preterm infants (one-fifth with gestational age ≤32 weeks) requiring medical treatment and technical support (e.g., use of incubator, respirator, continuous positive airway pressure, and feeding tube), as well as constant observing and monitoring in order to promptly intervene in case of acute situations. The unit had two intensive-care rooms (open heated cots under radiant warmers and incubators), one sub-intensive-care (incubators), and one ordinary care room (open cots and no breathing support). Parents were admitted in the intensive- and sub-intensive-care rooms from 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. and in the ordinary care room 24 h/day. The unit practiced family-centered care. The program was based on providing parents with psychological support and information on how approaching the preterm infant and then, as soon as the infant could be moved out of the incubator, encouraging daily skin-to-skin practice and the involvement of parents in infant care.

Participants

The participants were 20 Italian fathers of preterm infants born and hospitalized in the NICU. The participants were enrolled through purposive sampling until data saturation—i.e., when no new themes from the interviews were identified by the researchers. Four fathers refused to join the study. The criteria for inclusion were: (1) being the father of (an) alive preterm infant(s) born before 34 weeks PMA [8, 27], (2) being Italian, (3) being heterosexual, and (4) cohabiting with the infant’s mother. The criteria for exclusion were: (1) psychiatric illness, (2) issues with drug or substance abuse, (3) a partner with psychiatric illness, (4) a partner’s issues with drug or substance abuse, and (5) being an adoptive parent.

Data collection

Ethnographic observation

First, the researcher conducted participant observation with the parents in the NICU in order (1) to establish a working relationship [28], and (2) to obtain rich qualitative data from informal talks and direct observations of the fathers’ social interactions and emotional responses in the NICU. The ethnographic observation was conducted twice or more per week for the entire duration of the data collection. Field notes were focused on the fathers’ verbal and nonverbal behaviors and were written as soon as possible after the observation periods. As far as possible, the notes were made so that they approximated to a word-for-word record and represented non-verbal behaviors in relatively concrete, descriptive terms. All field notes were included in the qualitative analysis.

Semi-structured interviews

Second, semi-structured interviews were conducted with the fathers in a private hospital room after the infant’s medical condition stabilized, that is, after a median length of 43.5 days (mean = 52.5, SD = 31.7) in NICU. The individual face-to-face interviews were audio-recorded and lasted ~45 min. No other person was present. The interview consisted of 16 open-ended questions: seven questions on the fathers’ experiences of supporting their partners, hiding or sharing their worries, emotional states and stress with them, feelings while observing maternal caregiving, couple relationship during their preterm infant’s stay in the NICU (findings from these questions are discussed in this study); three background questions on their NICU experience; and six questions about the fathers’ experiences with their preterm neonate(s), which were reported in a separate peer-reviewed paper [29].

Self-report questionnaires

Thirdly, both fathers and mothers completed (a) a questionnaire on socio-demographic information, (b) the Italian version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CED-S) [30] to evaluate (roughly) depressive symptoms, and (c) the Italian version of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) [31] to evaluate the level of satisfaction within the couple’s relationship. Data from all questionnaires are presented in Table 1.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the Ethical Committee for Clinical Trials of the Verona and Rovigo Provinces (reference no. 569CESC). All participants provided written informed consent.

Data analysis

Qualitative analysis

Each interview was transcribed verbatim, and all potential identifiers of person or place were anonymized. The interviewer verified all transcripts by listening to the audio-recording and checking their accuracy. At the end of each transcript, the interviewer added information obtained through informal talks with the fathers during participant observation in the NICU. Because this study aimed to understand the participants’ lived experiences and how they made sense of those experiences, a thematic content analysis [32] was applied to the transcripts by two coders independent of the interviewer. The two coders independently generated initial codes of interest from the transcript of the first ten interviews. All codes were compared and contrasted, and then examined and discussed with the involvement of the first author so that potential themes could be identified. The goodness of the themes was checked in relation to the initial codes. A clear definition and a name for each theme were then generated. Then, the coders analyzed the data within the defined themes. Data were managed using NVivo 11 (QSR International, USA). Finally, the themes emerging from the thematic content analysis of the interviews were checked for consistency with the observations made during the participant observation in NICU.

Quantitative analysis

A cluster analysis was applied to the themes that emerged from the qualitative analysis of the fathers’ narratives to identify possible profiles of fathers’ experiences with their partners after the premature birth, during their infant’s stay in the NICU. The stability of the identified clusters was verified by running the analysis several times with records randomly sorted. Then, a set of simple categorical regressions with optimal scaling (CATREG) was performed to examine any association between “belonging to a given cluster” and “fathers’ and mothers’ characteristics” (see Table 1) as possible explanatory variables. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 23.

Validity and reliability

A triangulation method was used in order to develop a comprehensive understanding of the fathers’ experiences and to test validity [33]. Information from different sources was explored: the interviews which were coded by independent coders, and the participant observation which was conducted in the NICU by the main researcher. Inter-coder reliability was calculated on 20% of the interviews: each time both of the two independent coders attributed the same theme code—or did not attribute any theme code—to the same sentence/paragraph of the transcript, it was considered agreement; otherwise, it was considered disagreement. The average agreement percentage was 85.

Results

Sample characteristics

Parents’ and infants’ characteristics are presented, respectively, in Tables 1 and 2. The mean family socioeconomic status (SES) based on the Pierrehumbert [34] four-point scoring system indicated‚ on average‚ a middle-class family SES. Mothers’ mean CES-D score suggested depressive symptoms and was higher than that of fathers. Fathers’ and mothers’ DAS scores were consistent and indicated high dyadic adjustment and absence of distress within the couple relationship. No parent had prior experience of children either admitted to NICU or affected by major health problems.

Main themes identified from fathers’ interviews (aim 1)

Three main themes were identified. Table 3 provides illustrative quotes for each theme that occurred. The quotes in Table 3 are referred to by the father’s ID number in the text. The original quotes were translated from Italian into English.

Support for mother

All the fathers mentioned that they had provided support to their partner regardless of their worries about the infant’s medical status. From the fathers’ statements, four subthemes emerged.

Putting mother’s and infant’s needs first

Seventeen fathers (85%) said they had neglected or put aside their own needs for support and relaxation to take care of their partner and infant (ID 5). When the mother experienced postpartum complications (five cases), fathers divided their worries and attentions almost equally between partner and infant. These fathers spoke about the fear of losing both partner and infant(s) and said they had been going back and forth between them in the first hours and days after birth (ID 16). In the other cases, fathers were more engaged with the infant during the standard period of the mothers’ bed rest consequent to cesarean section (ID 11). Four of these seventeen fathers had revealed their own needs and worries to their partner when the infant’s medical condition had improved and permission to bring him/her home had been obtained (ID 7). The other fathers had postponed this revelation after the baby’s discharge from the NICU (ID 20). Only three fathers (15%) said they put their own needs at the same level as their partner’s (ID 3).

Hiding worries and negative emotions

Eighteen fathers (90%) said that from birth, in order to support their partner, they had omitted to mention—and sometimes lied about—their worries and fears about the infant’s health (ID 20). However, for four of these fathers, their emotional experience was so intensethat they broke down and cried in front of their partners during the recovery period; two of them felt guilty because they thought this behavior could burden the partner (ID 5). Only two fathers (10%) reported having shared their negative feelings with their partner from the beginning (ID 17).

Counteracting the sense of guilt

Seven fathers (35%) reported that their partners felt they were responsible for the infant’s preterm birth and/or had feelings of failure about it, and that they had tried to argue that there was no fault involved (ID 8). However, two of these fathers shared their partners’ sense of responsibility and/or failure: in one case, this was related to the feeling they had transmitted a genetic defect; in the other case, it was related to the feeling that the mother had not rested enough during pregnancy. In both cases, the sense of responsibility was believed to be irrational (ID 15).

Fear that the mother would reject the child

Five fathers (25%) said that, initially, their partners expressed the fear of not being able to look at their preterm infant or not recognizing him/her as her child. The fathers’ common response was twofold: fear, and asking themselves what they could do if she did reject the preterm infant. In two cases, the fear vanished as soon as the mother saw the infant (ID 13). In the three cases in which mothers had refused, initially (1–5 days), to spend time with their infant, the fathers said they had tried to reassure their partner about her reaction and never forced her to see the infant (ID 5). Once the infant’s medical condition improved, these fathers felt relieved of the enormous weight of coping alone and felt more relaxed and confident about the future (ID 6).

Mother’s care for the infant

Observing mother engaged in caregiving

Nineteen fathers (95%) experienced positive feelings (joy, tenderness, pride, and serenity) when seeing their partner caring for the infant (ID 1). Only one father reported feeling less joyful because of the hospital situation. For all the fathers, the positive feelings were heightened by their awareness of the risks, difficulties and worries about their infant’s health (ID 9). These positive feelings were not weakened by any awkwardness or sense of fault that emerged during their partner’s caregiving (ID 3). Ten fathers (50%) also said that watching their partner engaged in caregiving routine had represented a sort of return to normality, the achievement of a condition of completeness in which they felt they were now a “normal” family (ID 15).

Mother has “something extra”

Six fathers (30%) explicitly said that their partner had “something extra” in caring for the infant (ID 7) and described a special bond between mother and infant, a bond built during pregnancy, “when the baby was in her mother’s belly”. One of these fathers reported that it was more beautiful for him to see the mother, rather than himself, holding their son (ID 7). Four fathers, though, described themselves as directly involved in caregiving equally with the mother (ID 16), explaining that saying “mother has something extra” did not mean that they perceived themselves as less necessary for the infant’s development or less involved than the mother, but that parents may have different roles.

Couple relationship

Participants spoke about their relationship with their partner.

Collaboration

Nineteen fathers (95%) reported that their collaboration with their partner on the division of roles and tasks between them was good (ID 15).

Bond

Twelve fathers (60%) felt that the couple’s bond had been strengthened by the experience of the preterm birth and the stay in the NICU. However, these fathers did not exclude the possibility that this strengthening would have happened with a full-term birth (ID 14). Seven fathers felt no differences between the couple’s bond before and after the preterm birth (ID 2). The remaining father experienced a deterioration of the couple’s bond (ID 18); it should be noted, however, that in this case the newborn’s medical condition was extremely critical.

Clusters of fathers’ partnership experiences (aim 2)

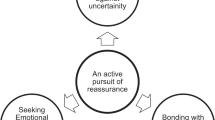

Cluster analysis applied to themes that emerged from the qualitative analysis of the interviews identified three clusters of fathers based on their partnership experience; we named these clusters “Protective partners” (10 fathers), “Defended partners” (7 fathers) and “Sharing partners” (3 fathers). Clusters were characterized by the following predictors (in order of importance): (1) putting mother’s needs first (1.00); (2) couple bond strengthened by the preterm birth (0.64); (3) hiding worries and negative emotions (0.63); (4) strong emotional stress (which combines the subthemes “counteracting the sense of guilt” and “fear that mother will reject the child”) (0.32). Only the feeling of being “back to normality” while observing the mother engaged in caregiving did not distinguish any cluster (0.02).

The “protective partners” omitted to mention their own worries and fears about the infant’s health and sometimes lied about them, and neglected or put aside their own needs for support in order to take care of their partner. Their couple bond was strengthened by the difficult emotional experience of the preterm birth and the subsequent stay in the NICU. These fathers may or may not have experienced strong emotional stress due to their own or their partners’ sense of responsibility and/or failure for the preterm birth.

Similarly, the “defended partners” neglected or put aside their worries and fears about the infant’s health and their own emotional needs in order to support their partner. However, unlike fathers in the first cluster, they experienced no differences in the couple bond after the preterm birth or a bond weakening in front of the difficulties of the NICU experience. Furthermore, the majority of these fathers did not report having experienced any strong emotional stress. Although both “protective” and “defended” fathers shared little of their negative feelings with their partners, the “defended” ones appeared to do this at the cost of weakening the bond with their partners, suggesting that the absence of sharing in this cluster was driven by self-defense and self-protection from negative emotions.

In contrast, the “sharing partners” experienced strong emotional stress and put their own needs and worries at the same level as their partner’s. Indeed, most of them shared their emotional states with their partner during the NICU stay, and this sharing contributed to strengthening the bond between them.

Then, a set of simple categorical regressions with optimal scaling was applied in order to examine the relationship between belonging to one of the three clusters as the response variable and both fathers’ and mothers’ characteristics, including the family SES and being first-time parents (see Table 1), as well as the infant’s perinatal risk score (Table 2), as possible explanatory variables. The regression analysis showed that belonging to a given cluster of fathers’ partnership experiences during the preterm infant’s stay in the NICU was significantly associated with the fathers’ marital satisfaction (80 and 100% above the DAS cut-off in “protective partners” and “sharing partners” clusters, respectively, but only 43% above the cut-off in “defended partners” cluster; β = 0.459, F(1) = 5.51, p = 0.031). No associations were found between belonging to any of the three clusters and any other variables explored.

Discussion

This study had two aims: (1) to explore fathers’ experiences of supporting their partner and of their relationship with their partner during their preterm infant’s stay in the NICU, and (2) to assess whether different profiles of the fathers’ partnership experience could be identified from their interviews and eventually associated with any characteristics of the fathers and/or their partners. The results are very interesting and add to the still scant literature on fathers’ experiences during their preterm infants’ hospitalization in the NICU. However, our findings are from one level III NICU located in Northern Italy and focused on a specific population (i.e., preterm infants in typical Italian nuclear families defined by a heterosexual parental couple); hence they might not be generalizable to other settings or populations.

Most of the fathers interviewed believed they had the role of protecting both the preterm infant and the mother, looking after the family’s best interests; however, at the same time, they felt that they themselves needed support. This finding is consistent with previous studies [21, 35,36,37,38]. When the mothers presented severe postpartum complications, the fathers were almost equally concerned about mother and infant, which contrasts with a Norwegian study [21] where the fathers were more concerned about the mother. However, this might be explained by the fact that in the Norwegian study, the interviews were performed between 1 and 6 months after discharge from the NICU, which is when infants were no longer at medical risk. In addition, possible variations in family culture between the countries might have contributed to the different finding.

The fathers’ most common way of protecting their partners from further upheavals was to avoid showing—and, in some cases, to hide—their own worries and feelings. However, all the fathers’ reports suggest that, behind their idealized role as the protector of their partner, they might be hiding the deployment of defense mechanisms protecting themselves from the reality of their own inner experience. Indeed, we hypothesize that the fathers belonging to the “defended partners” cluster were driven by defenses against their worries and negative emotional states and stress, whereas the “protective partners” were motivated by more purely altruistic reasons. It follows that the real magnitude of the paternal distress tends to be invisible not only to the partner and the NICU staff, which is consistent with previous studies [21, 39, 40], but also to the fathers themselves.

Several studies [41,42,43] have shown mothers’ feelings of guilt and continual questioning of whether they could have prevented the preterm birth. Some studies [44,45,46] have also revealed maternal rejection of the infant. Similarly, about a third of our participants reported these experiences on the part of their partners, and that they tried to offer verbal reassurance and foster the establishment of the mother–infant bond. We found that observing the partner engaged in daily care routine for the infant is important to fathers. They reported feeling satisfaction in being involved in their infant’s care but also being happy to step backand leave room for the partner’s caregiving and emotional closeness to the infant.

Concerning the couple relationship, the fact that the degree of collaboration between partners in the division of infant-care tasks was regarded as good regardless of the quality of the couple bond suggests that both parents put the baby’s wellbeing first. Furthermore, in line with the studies on the couple relationship after the death of a child [47, 48], our results suggest that preterm birth can influence the couple relationship both positively and negatively. Interestingly, marital satisfaction was the only explanatory variable for the fathers’ belonging to one of the three identified clusters. The significant association between the level of marital satisfaction and the different clusters allow us to hypothesize that the quality of the couple relationship plays a crucial role in increasing the fathers’ emotional awareness (which seems to be higher in the “protective partners” and “sharing partners” clusters), and, probably, vice versa.

Previous studies [21, 38, 39, 49] have found that fathers try to protect themselves and their partners from the emotional impact of becoming a parent in a NICU by adopting stereotypical masculine behaviors and emotional inexpression or withdrawal. Our results, showing that the father’s needs, feelings, and difficulties are often hidden and silent, are partially consistent with the previous ones, but our findings also show that keeping feelings silent demands a great deal of both physical and emotional energy. So much that three participants were crying during the interview, and they took some time to recover fully before rejoining their partners. The fathers’ emotional illness is more difficult to acknowledge than that of the mothers. All the fathers reported spontaneously that speaking about their feelings and worries was a positive experience, with possible beneficial effects after the interview. For example, two of them mentioned the improvement of the quality of their father–infant interaction, and another reported an increase in the time spent in the NICU. We might, therefore, regard interviews with fathers as a routine assessment tool for reviewing the emotional health of fathers of preterm infants admitted to a NICU, in line with other research [50]. Better emotional conditions in fathers maypositively influence both the support provided to their partners and their involvement with the infant. It may here be mentioned that the Italian government has a national paid leave policy whereby employed new mothers are entitled to have twenty weeks of leave at 80% of their salary along with guaranteed job security. Fathers are eligible for the same paid leave if the mother is not available due to abandonment, illness, or death. None of the fathers in our study took a paid leave.

Furthermore, it should be noted that the mean CES-D score for fathers was 14.9 (SD = 7.7), which indicates that they, unlike mothers, did not show depressive symptoms to a significant extent. We believe that this reinforces the value of the themes that emerged from the interviews because such themes seem not to be dictated by negative emotional states. Fathers did not experience the trauma of the preterm birth in their bodies and were less physically close to the preterm infants in the immediate postpartum period. These factors might contribute to a possible greater “psychological distance” in fathers. Nevertheless, it is also possible that for a subsample of fathers, those in the “defended partners” cluster, some depressive thoughts were inhibited by a predominant pattern of defense mechanisms. In addition, some recent studies have suggested that depressive symptoms in men may be milder and less clearly defined than in women [51, 52].

Finally, the present study was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been disrupting Italian perinatal health services [53] and psychiatric and psychological intervention services [54]. Concerning the NICU, family-centered care is challenged by the ongoing global health emergency, and adverse effects often experienced by parents following a preterm infant’s hospitalization can be more severe and long-lasting because of a cumulative effect [13]. Hence, nowadays, the fathers’ experiences of supporting their partners during their child’s stay in the NICU might differ.

Limitations and strengths

Our study has a number of limitations. First, it is based primarily on fathers’ self-reports, which might reflect neither the actual support they gave to their partners nor their partners’ perception of the support received from the fathers. This potential problem is reduced by the fact that ethnographic observations in the NICU are broadly consistent with the information provided by the fathers. Second, since note-taking during participant observation in the NICU would be disruptive for fathers’ spontaneous behaviors, field notes were written up as soon as possible after the periods of observation. This entailed the risk of forgetting or confusing meaningful episodes and, more generally, a potential decrease in the quality of the notes. Third, the self-selection of fathers who agreed to be interviewed could introduce a bias in the themes that emerged from the interviews. In this regard, however, it is important to note that more than three-quarters of fathers agreed to be interviewed. Fourth, the timing of the interview in relation to the infant’s NICU stay was quite variable, and this could have influenced our findings. Finally, the findings may not be generalizable to other preterm fathers, whose experiences may differ along cultural lines [55] or as a function of the NICU staff attitudes and visiting policies.

Our study also has a number of advantages: (a) its use of a multi-method approach; (b) its use of a male interviewer (fathers prefer to talk to a male researcher or health care provider) [49] not associated with the hospital, because this may allow more open and honest responses [22]; (c) a larger sample size than in other studies based on in-depth interviews [18]; and (d) its implications for family support in the NICU (cf. Conclusion).

Conclusion

This study makes an original contribution to the scant literature on psychological aspects of fathers of premature infants. Our findings may help healthcare professionals to better understand the fathers’ experiences of supporting their partners during their preterm infant’s stay in the NICU, showing that the magnitude of the preterm fathers’ distress and their need to be supported tend to be hidden. Thus, our findings suggest that it is vital to provide these fathers with specific psychological support and that interviews may be profitably used as a routine tool to this aim. Supporting fathers may improve their emotional states and their involvement in infant care in the NICU, hence be beneficial to mothers and infants. Additionally, our study highlights the need for regular and direct observation of fathers’ interactions with their partner as an assessment for understanding the degree of their ability to take care of themselves and their loved ones. Future research must continue to explore the couple relationship between fathers and mothers of preterm infants, as this appears to be a crucial factor for the health status of preterm parents.

References

Treyvaud K, Spittle A, Anderson PJ, O’Brien K. A multilayered approach is needed in the NICU to support parents after the preterm birth of their infant. Early Hum Dev. 2019;139:104838 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2019.104838

Whittingham K, Boyd RN, Sanders MR, Colditz P. Parenting and prematurity: understanding parent experience and preferences for support. J Child Fam Stud. 2013;23:1050–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9762-x.

Amorim M, Alves E, Kelly-Irving M, Silva S. Needs of parents of very preterm infants in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: a mixed methods study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2019;54:88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2019.05.003

Haddad S, Dennis C-L, Shah PS, Stremler R. Sleep in parents of preterm infants: a systematic review. Midwifery. 2019;73:35–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2019.01.009

Stefana A, Lavelli M. I genitori dei bambini prematuri una prospettiva psicodinamica [parents of premature babies: a psychodynamic perspective]. Med Bambino. 2016;35:327–32.

Paulson JF, Bazemore SD, Goodman JH, Leiferman JA. The course and interrelationship of maternal and paternal perinatal depression. Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2016;19:655–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0598-4

Di Blasio P, Caravita SCS, Camisasca E, Milani L. Parenting stress and posttraumatic stress symptoms after childbirth. a longitudinal study. J Dev Psychol. 2011;3:71–91.

Forcada-Guex M, Borghini A, Pierrehumbert B, Ansermet F, Muller-Nix C. Prematurity, maternal posttraumatic stress and consequences on the mother-infant relationship. Early Hum Dev. 2011;87:21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.09.006

Stefana A, Lavelli M, Rossi G, Beebe B. Interactive sequences between fathers and preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. Early Hum Dev. 2020;140:104888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2019.104888

Lavelli M, Stefana A, Lee, SH, Beebe B. Preterm infant contingent communication in the NICU with mothers vs. fathers. Dev Psychol (accepted for publication).

Korja R, Latva R, Lehtonen L. The effects of preterm birth on mother-infant interaction and attachment during the infant’s first two years. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91:164–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01304.x

Treyvaud K. Parent and family outcomes following very preterm or very low birth weight birth: a review. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;19:131–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2013.10.008

Cena L, Biban P, Janos J, Lavelli M, Langfus J, Tsai A, et al. The collateral impact of COVID-19 emergency on neonatal intensive care units and family-centered care: challenges and opportunities. Front Psychol. 2021;12:630594 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.630594

O’Brien K, Robson K, Bracht M, Cruz M, Lui K, Alvaro R, et al. Effectiveness of Family Integrated Care in neonatal intensive care units on infant and parent outcomes: a multicentre, multinational, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2:245–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30039-7

Montirosso R, Del Prete A, Bellu R, Tronick E, Borgatti R. Level of NICU Quality of developmental care and neurobehavioral performance in very preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1129–e1137. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0813

Lundqvist P, Weis J, Sivberg B. Parents’ journey caring for a preterm infant until discharge from hospital‐based neonatal home care—a challenging process to cope with. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:2966–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14891

Stefana A, Lavelli M. What is hindering research on psychological aspects of fathers of premature infants? Minerva Pediatr. 2018;70:204–6. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0026-4946.16.04618-1

Provenzi L, Santoro E. The lived experience of fathers of preterm infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: a systematic review of qualitative studies. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:1784–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12828

Huhtala M, Korja R, Lehtonen L, Haataja L, Lapinleimu H, Rautava P. Associations between parental psychological well-being and socio-emotional development in 5-year-old preterm children. Early Hum Dev. 2014;90:119–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.12.009

McMahon GE, Spencer-Smith MM, Pace CC, Spittle AJ, Stedall P, Richardson K, et al. Influence of fathers’ early parenting on the development of children born very preterm and full term. J Pediatr. 2019;205:195–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.073

Hagen IH, Iversen VC, Svindseth MF. Differences and similarities between mothers and fathers of premature children: a qualitative study of parents’ coping experiences in a neonatal intensive care unit. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16:92 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0631-9

Sawyer A, Rabe H, Abbott J, Gyte G, Duley L, Ayers S. Parents’ experiences and satisfaction with care during the birth of their very preterm baby: a qualitative study. BJOG. 2013;120:637–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12104

Iafrate R, Bertoni A, Margola D, Cigoli V, Acitelli LK. The link between perceptual congruence and couple relationship satisfaction in dyadic coping. Eur Psychol. 2012;17:73–82. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000069

Cigoli V, Scabini E. Family identity. Routledge, 2017. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410617712.

Dykes F, Flacking R. Ethnographic research in maternal and child health. Routledge, 2015. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315762319.

Stefana A, Lavelli M. Parental engagement and early interactions with preterm infants during the stay in the neonatal intensive care unit: protocol of a mixed-method and longitudinal study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e013824. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013824

Welch MG, Hofer MA, Brunelli SA, Stark RI, Andrews HF, Austin J, et al. Family nurture intervention (FNI): methods and treatment protocol of a randomized controlled trial in the NICU. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-12-14

Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Wampold BE, Horvath AO. The alliance in adult psychotherapy: a meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy. 2018;55:316–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000172

Stefana A, Padovani EM, Biban P, Lavelli M. Fathers’ experiences with their preterm babies admitted to neonatal intensive care unit: a multi-method study. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:1090–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13527

Fava GA. Assessing depressive symptoms across cultures: Italian validation of the CES-D self-rating scale. J Clin Psychol. 1983;39:249–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(198303)39:2%3C249::aid-jclp2270390218%3E3.0.co;2-y

Gentili P, Contreras L, Cassaniti M, D’Arista F. La Dyadic Adjustment Scale. Una misura dell’adattamento di coppia. Minerva Psichiatr. 2002;43:107–16.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41:545–7. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.onf.545-547

Pierrehumbert B. Parental post-traumatic reactions after premature birth: implications for sleeping and eating problems in the infant. Arch Dis Child—Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88:400F–404. https://doi.org/10.1136/fn.88.5.f400

Hallström I, Runesson I, Elander G. Observed parental needs during their child’s hospitalization. J Pediatr Nurs. 2002;17:140–8. https://doi.org/10.1053/jpdn.2002.123020

John WS, Cameron C, McVeigh C. Meeting the challenge of new fatherhood during the early weeks. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2005;34:180–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884217505274699

Lindberg B, Axelsson K, Öhrling K. The birth of premature infants: experiences from the fathers’ perspective. J Neonatal Nurs. 2007;13:142–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnn.2007.05.004

Noergaard B, Ammentorp J, Fenger-Gron J, Kofoed P-E, Johannessen H, Thibeau S. Fathers’ needs and masculinity dilemmas in a neonatal intensive care unit in denmark. Adv Neonatal Care. 2017;17:E13–E22. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0000000000000395

Hugill K, Letherby G, Reid T, Lavender T. Experiences of fathers shortly after the birth of their preterm infants. JOGNN. 2013;42:655–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12256

Ireland J, Minesh Khashu, Cescutti-Butler L, van Teijlingen E, Hewitt-Taylor J. Experiences of fathers with babies admitted to neonatal care units: a review of the literature. J Neonatal Nurs. 2016;22:171–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnn.2016.01.006

Arnold L, Sawyer A, Rabe H, Abbott J, Gyte G, Duley L, et al. Parents’ first moments with their very preterm babies: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002487 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002487

Garel M, Dardennes M, Blondel B. Mothers’ psychological distress 1 year after very preterm childbirth. Results epipage qualitative study Child Care Health Dev. 2007;33:137–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00663.x

Koliouli F, Gaudron CZ, Raynaud J-P. Life experiences of French premature fathers: a qualitative study. J Neonatal Nurs. 2016;22:244–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnn.2016.04.003

Heidari H, Hasanpour M, Fooladi M. The Iranian parents of premature infants in NICU experience stigma of shame. Med Arch. 2012;66:35. https://doi.org/10.5455/medarh.2012.66.35-40

Pector EA, Smith-Levitin M. Mourning and psychological issues in multiple birth loss. Semin Neonatol. 2002;7:247–56. https://doi.org/10.1053/siny.2002.0112

Sajaniemi N, Mäkelä J, Salokorpi T, von Wendt L, Hämäläinen T, Hakamies-Blomqvist L. Cognitive performance and attachment patterns at four years of age in extremely low birth weight infants after early intervention. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;10:122–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007870170035

Albuquerque S, Pereira M, Narciso I. Couple’s relationship after the death of a child: a systematic review. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25:30–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0219-2

Cena L, Lazzaroni S, Stefana A. The psychological effects of stillbirth on parents: a qualitative evidence synthesis of psychoanalytic literature. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2021;67:329–50. https://doi.org/10.13109/zptm.2021.67.3.329

Arockiasamy V, Holsti L, Albersheim S. Fathers’ experiences in the neonatal intensive care unit: a search for control. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e215–e222. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-1005

Candelori C, Trumello C, Babore A, Keren M, Romanelli R. The experience of premature birth for fathers: the application of the Clinical Interview for Parents of High-Risk Infants (CLIP) to an Italian sample. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1444. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01444

Stefana A, Lavelli M. Fathers of preterm infants: a resource to invest on [I padri dei bambini nati pretermine: una risorsa su cui investire]. Psicologia Clin dello Svilupp. 2016;20:165–88. https://doi.org/10.1449/84129

Baldoni F, Giannotti M. Perinatal distress in fathers: toward a gender-based screening of paternal perinatal depressive and affective disorders. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1892. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01892

Cena L, Rota M, Calza S, Massardi B, Trainini A, Stefana A. Estimating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on perinatal health care services in Italy. Front Public Health. 2021;9:701638. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.701638.

Stefana A, Youngstrom EA, Hopwood CJ, Dakanalis A. The COVID-19 pandemic brings a second wave of social isolation and disrupted services. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;270:785–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-020-01137-8

Stefana A. Mourning the death of a foreign child. Indian J Pediatr. 2017;84:245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-016-2264-2

Scheiner AP, Sexton ME. Prediction of developmental outcome using a perinatal risk inventory. Pediatrics 1991;88:1135–43.

Funding

The first author received doctoral scholarships for this work from the University of Verona.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: AS; methodology: AS; qualitative analysis: AS; quantitative analysis: ML; writing—original draft preparation: AS; writing—review and editing: AS, ML, PB, EMP. All authors approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41372_2021_1195_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Fathers’ experiences of supporting their partners during their preterm infant’s stay in the neonatal intensive care unit: a multi-method study

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stefana, A., Biban, P., Padovani, E.M. et al. Fathers’ experiences of supporting their partners during their preterm infant’s stay in the neonatal intensive care unit: a multi-method study. J Perinatol 42, 714–722 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01195-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01195-3