Abstract

Objective

To determine population-based risks of preterm birth associated with vasa previa.

Study design

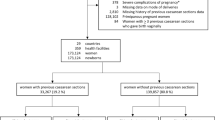

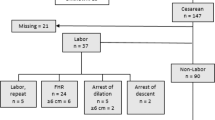

Included were 945,950 singleton, live birth cesarean deliveries with and without vasa previa (gestational ages 24–41 weeks) in California between 2007 and 2012. Odds ratios (ORs) of preterm birth were estimated using logistic regression.

Results

In total, 586 were complicated by vasa previa (0.06%). In total, 369 (63%) of those with vasa previa were delivered <37 weeks, compared with 91,662 (10%) of those without. Odds of extreme and very preterm birth were substantially higher for pregnancies with vasa previa even after controlling for comorbidities known to contribute to prematurity, with ORs of 4.6 (95% confidence interval, CI: 1.7–12.5) and 16.0 (95% CI: 10.3–24.8), respectively.

Conclusion

Based on these population-based data, most patients with vasa previa are delivered between 32 and 36 weeks gestation; however, a clinically significant portion occur before 32 weeks. These data are helpful in counseling patients with vasa previa regarding prematurity risk.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bronsteen R, Whitten A, Balasubramanian M, Lee W, Lorenz R, Redman M, et al. Vasa previa: clinical presentations, outcomes, and implications for management. Obstet & Gynecol. 2013;122(2 PART 1):352–7.

Sullivan EA, Javid N, Duncombe G, Li Z, Safi N, Cincotta R, et al. Vasa Previa diagnosis, clinical practice, and outcomes in Australia. Obstet & Gynecol. 2017;130:591–8.

Fung T, Lau T. Poor perinatal outcome associated with vasa previa: is it preventable? A report of three cases and review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;12:430–3.

Baulies S, Maiz N, Munoz A, Torrents M, Echevarria M, Serra B. Prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of vasa praevia and analysis of risk factors. Prenat Diagn. 2007;27:595–9.

Hasegawa J, Farina A, Nakamura M, Matsuoka R, Ichizuka K, Sekizawa A, et al. Analysis of the ultrasonographic findings predictive of vasa previa. Prenat Diagn. 2010;30:1121–5.

Schachter M, Tovbin Y, Arieli S, Friedler S, Ron-El R, Sherman D. In vitro fertilization is a risk factor for vasa previa. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:642–3.

Burton G, Saunders D. Vasa praevia: another cause for concern in in vitro fertilization pregnancies. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;28:180–1.

Sinkey RG, Odibo AO, Dashe JS. # 37: Diagnosis and management of vasa previa. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:615–9.

Oyelese Y, Catanzarite V, Prefumo F, Lashley S, Schachter M, Tovbin Y, et al. Vasa previa: the impact of prenatal diagnosis on outcomes. Obstet & Gynecol. 2004;103:937–42.

Smorgick N, Tovbin Y, Ushakov F, Vaknin Z, Barzilay B, Herman A, et al. Is neonatal risk from vasa previa preventable? The 20‐year experience from a single medical center. J Clin Ultrasound. 2010;38:118–22.

Swank ML, Garite TJ, Maurel K, Das A, Perlow JH, Combs CA, et al. Vasa previa: diagnosis and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:223. e1–6.

Catanzarite V, Cousins L, Daneshmand S, Schwendemann W, Casele H, Adamczak J, et al. Prenatally diagnosed vasa previa. Obstet & Gynecol. 2016;128:1153–61.

Lyndon A, Lee HC, Gilbert WM, Gould JB, Lee KA. Maternal morbidity during childbirth hospitalization in California. J Matern-Fetal & Neonatal Med. 2012;25:2529–35.

WHO. BMI Classification. http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html.

WHO. Preterm Birth 2018. http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth.

Blencowe H, Cousens S, Chou D, Oestergaard M, Say L, Moller A-B, et al. Born too soon: the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod Health. 2013;10:S2.

Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet & Gynecol. 1996;87:163–8.

Oken E, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards J, Gillman MW. A nearly continuous measure of birth weight for gestational age using a United States national reference. BMC Pediatr. 2003;3:6.

Ruiter L, Kok N, Limpens J, Derks J, De Graaf I, Mol B, et al. Incidence of and risk indicators for vasa praevia: a systematic review. BJOG: Int J Obstet & Gynaecol. 2016;123:1278–87.

American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. AIUM practice guideline for the performance of obstetric ultrasound examinations. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32:1083–101.

Salomon L, Alfirevic Z, Berghella V, Bilardo C, Hernandez-Andrade E, Johnsen S, et al. Practice guidelines for performance of the routine mid‐trimester fetal ultrasound scan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37:116–26.

No 27 Green-top Guideline. Placenta praevia, placenta praevia accreta and vasa praevia: diagnosis and management. London: RCOG; 2011. p. 1–26.

Rebarber A, Dolin C, Fox NS, Klauser CK, Saltzman DH, Roman AS. Natural history of vasa previa across gestation using a screening protocol. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33:141–7.

Acknowledgements

Funding from the March of Dimes (MOD) supported this research. The MOD had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. Paper presentation information: These findings were presented at the 37th Annual Pregnancy Meeting of the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine in Las Vegas, Nevada; January 23–28, 2017.

Author contributions

AY-M, AIG, JAM, YJB, YYE-S, DKS, and GMS contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of the data, drafting of the article and revising it critically along with performing a final review prior to its submission for publication. JAM and GMS contributed to the analysis of the data.

Funding

Funding from the March of Dimes (MOD) supported this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yeaton-Massey, A., Girsen, A.I., Mayo, J.A. et al. Vasa previa and extreme prematurity: a population-based study. J Perinatol 39, 475–480 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-019-0319-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-019-0319-8