Abstract

Background

Fugacity, the driving force for transdermal uptake of chemicals, can be difficult to predict based only on the composition of complex, non-ideal mixtures such as personal care products.

Objective

Compare the predicted transdermal uptake of benzophenone-3 (BP-3) from sunscreen lotions, based on direct measurements of BP-3 fugacity in those products, to results of human subject experiments.

Methods

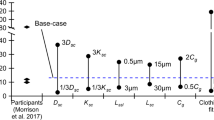

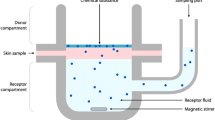

We measured fugacity relative to pure BP-3, for commercial sunscreens and laboratory mixtures, using a previously developed/solid-phase microextraction (SPME) method. The measured fugacity was combined with a transdermal uptake model to simulate urinary excretion rates of BP-3 resulting from sunscreen use. The model simulations were based on the reported conditions of four previously published human subject studies, accounting for area applied, time applied, showering and other factors.

Results

The fugacities of commercial lotions containing 3–6% w/w BP-3 were ~20% of the supercooled liquid vapor pressure. Simulated dermal uptake, based on these fugacities, are within a factor of 3 of the mean results reported from two human-subject studies. However, the model significantly underpredicts total excreted mass from two other human-subject studies. This discrepancy may be due to limitations in model inputs, such as fugacity of BP-3 in lotions used in those studies.

Significance

The results suggest that combining measured fugacity with such a model may provide order-of-magnitude accurate predictions of transdermal uptake of BP-3 from daily application of sunscreen products.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 6 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $43.17 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Pathak MA. Sunscreens: topical and systemic approaches for protection of human skin against harmful effects of solar radiation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0190-9622(82)70117-3.

Pathak MA. Sunscreens: topical and systemic approaches for the prevention of acute and chronic sun-induced skin reactions. Dermatol Clin. 1986;4:321–34.

Nash JF. Human safety and efficacy of ultraviolet filters and sunscreen products. Dermatol Clin. 2006;24:35–51.

Lautenschlager S, Wulf HC, Pittelkow MR. Photoprotection. Lancet. 2007;370:528–37.

Jansen R, Wang SQ, Burnett M, Osterwalder U, Lim HW. Photoprotection: Part I Photoprotection by naturally occurring, physical, and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:853.e1–853.e12.

Krause M, Klit A, Blomberg Jensen M, Søeborg T, Frederiksen H, Schlumpf M, et al. Sunscreens: are they beneficial for health? An overview of endocrine disrupting properties of UV-filters. Int J Androl. 2012;35:424–36.

Thompson SC, Jolley D, Marks R. Reduction of solar keratoses by regular sunscreen use. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1147–51.

Green A, Williams G, Neale R, Hart V, Leslie D, Parsons P, et al. Daily sunscreen application and betacarotene supplementation in prevention of basal-cell and squamous-cell carcinomas of the skin: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;354:723–9.

Dupuy A, Dunant A, Grob JJ. Randomized controlled trial testing the impact of high-protection sunscreens on sun-exposure behavior. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:950–6.

Hagedorn-Leweke U, Lippold BC. bsorption of sunscreens and other compounds through human skin in vivo: derivation of a method to predict maximum fluxes. Pharm Res J Am Assoc Pharm Sci. 1995;12:1354–60.

Treffel P, Gabard B. Skin penetration and sun protection factor of ultra-violet filters from two vehicles. Pharm Res. 1996;13:770–4.

Walters KA, Brain KR, Dressler WE, Green DM, Howes D, James VJ, et al. Percutaneous penetration of N-nitroso-N-methyldodecylamine through human skin in vitro: application from cosmetic vehicles. Food Chem Toxicol. 1997;35:705–12.

Hayden CGJ, Roberts MS, Benson HAE. Systemic absorption of sunscreen after topical application. Lancet. 1997;350:863–4.

Jiang R, Roberts MS, Collins DM, Benson HAE. Absorption of sunscreens across human skin: an evaluation of commercial products for children and adults. Br J Clin Pharm. 1999;48:635–7.

Gonzalez H, Farbrot A, Larkö O. Percutaneous absorption of benzophenone-3, a common component of topical sunscreens. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:691–4.

Janjua NR, Mogensen B, Andersson AM, Petersen JH, Henriksen M, Skakkebæk NE, et al. Systemic absorption of the sunscreens benzophenone-3, octyl- methoxycinnamate, and 3-(4-methyl-benzylidene) camphor after whole-body topical application and reproductive hormone levels in humans. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:57–61.

Kaidbey K, William Gange R. Comparison of methods for assessing photoprotection against ultraviolet A in vivo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:346–53.

Schlumpf M, Cotton B, Conscience M, Haller V, Steinmann B, Lichtensteiger W. In vitro and in vivo estrogenicity of UV screens. Environ Health Perspect. 2001. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.01109239.

Schreurs R, Lanser P, Seinen W, Van der Burg B. Estrogenic activity of UV filters determined by an in vitro reporter gene assay and an in vivo transgenic zebrafish assay. Arch Toxicol. 2002;76:257–61.

Ma R, Cotton B, Lichtensteiger W, Schlumpf MUV. filters with antagonistic action at androgen receptors in the MDA-kb2 cell transcriptional-activation assay. Toxicol Sci. 2003;74:43–50.

Witorsch RJ, Thomas JA. Personal care products and endocrine disruption: a critical review of the literature. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2010;40:1–30.

Wang SQ, Burnett ME, Lim HW. Safety of oxybenzone: putting numbers into perspective. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:865–6.

Chen M, Tang R, Fu G, Xu B, Zhu P, Qiao S, et al. Association of exposure to phenols and idiopathic male infertility. J Hazard Mater. 2013;250–251:115–21.

Tang R, Chen MJ, Ding GD, Chen XJ, Han XM, Zhou K, et al. Associations of prenatal exposure to phenols with birth outcomes. Environ Pollut. 2013;178:115–20.

Ghazipura M, McGowan R, Arslan A, Hossain T. Exposure to benzophenone-3 and reproductive toxicity: a systematic review of human and animal studies. Reprod Toxicol. 2017;73:175–83.

Kadry AM, Okereke CS, Abdel‐Rahman MS, Friedman MA, Davis RA. Pharmacokinetics of benzophenone‐3 after oral exposure in male rats. J Appl Toxicol. 1995;15:97–102.

Okereke CS, Kadry AM, Abdel-Rahman MS, Davis RA, Friedman MA. Metabolism of benzophenone-3 in rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 1993:21;788--91.

Wang L, Kannan K. Characteristic profiles of benzonphenone-3 and its derivatives in urine of children and adults from the United States and China. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:12532–8.

Suzuki T, Kitamura S, Khota R, Sugihara K, Fujimoto N, Ohta S. Estrogenic and antiandrogenic activities of 17 benzophenone derivatives used as UV stabilizers and sunscreens. Toxicol Appl Pharm. 2005;203:9–17.

Kunisue T, Chen Z, Buck Louis GM, Sundaram R, Hediger ML, Sun L, et al. Urinary concentrations of benzophenone-type UV filters in U.S. women and their association with endometriosis. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:4624–32.

Wolff MS, Engel SM, Berkowitz GS, Ye X, Silva MJ, Zhu C, et al. Prenatal phenol and phthalate exposures and birth outcomes. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1092–7.

Philippat C, Mortamais M, Chevrier C, Petit C, Calafat AM, Ye X, et al. Exposure to phthalates and phenols during pregnancy and offspring size at birth. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:464–70.

Ferguson KK, Meeker JD, Cantonwine DE, Mukherjee B, Pace GG, Weller D, et al. Environmental phenol associations with ultrasound and delivery measures of fetal growth. Environ Int. 2018;112:243–50.

Food and Drug Administration H. Labeling and effectiveness testing; sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Final rule Fed Regist 2011;76:35620–65.

Xue J, Liu W, Kannan K. Bisphenols, benzophenones, and bisphenol A diglycidyl ethers in textiles and infant clothing. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51:5279–86.

Li AJ, Kannan K. Elevated concentrations of bisphenols, benzophenones, and antimicrobials in pantyhose collected from six countries. Environ Sci Technol. 2018;52:10812–9.

European Commission. Scientific Committee on Consumer Products Benzophenone-3. 2008.

Sarveiya V, Risk S, Benson HAE. Liquid chromatographic assay for common sunscreen agents: application to in vivo assessment of skin penetration and systemic absorption in human volunteers. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2004;803:225–31.

Gonzalez H, Farbrot A, Larkö O, Wennberg AM. Percutaneous absorption of the sunscreen benzophenone-3 after repeated whole-body applications, with and without ultraviolet irradiation. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:337–40.

Eftekhari A, Frederiksen H, Andersson AM, Weschler CJ, Weschler CJ, Morrison G. Predicting transdermal uptake of phthalates and a paraben from cosmetic cream using the measured fugacity. Environ Sci Technol. 2020;54:7471–84.

Mackay D. Finding fugacity feasible. Environ Sci Technol. 1979;13:1218–23.

MacKay D, Arnot JA. The application of fugacity and activity to simulating the environmental fate of organic contaminants. J Chem Eng Data. 2011;56:1348–55.

Golding CJ, Gobas FAPC, Birch GF. A fugacity approach for assessing the bioaccumulation of hydrophobic organic compounds from estuarine sediment. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2008;27:1047–54.

Mackay D, Paterson S. Fugacity revisited: the fugacity approach to environmental transport. Environ Sci Technol. 1982;16:654A–660A.

Schramm KW. Environmental impact assessment (EIA): equilibrium fugacity calculations and worst case approach. Chemosphere. 1994;28:2151–71.

Mackay D, Paterson S. Fugacity approach for calculating near-source toxic substance concentrations and partitioning in lakes. Water Pollut Res J Can. 1981;16:59–70.

Lago AF, Jimenez P, Herrero R, Dávalos JZ, Abboud JLM. Thermochemistry and gas-phase ion energetics of 2-hydroxy-4-methoxy- benzophenone (oxybenzone). J Phys Chem A. 2008;112:3201–8.

Duffy E, Jacobs MR, Kirby B, Morrin A. Probing skin physiology through the volatile footprint: Discriminating volatile emissions before and after acute barrier disruption. Exp Dermatol. 2017;26:919–25.

Eftekhari A, Hill JT, Morrison GC. Transdermal uptake of benzophenone-3 from clothing: comparison of human participant results to model predictions. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2020;31:149–57.

Okereke CS, Abdel-Rhaman MS, Friedman MA. Disposition of benzophenone-3 after dermal administration in male rats. Toxicol Lett. 1994;73:113–22.

Wang TF, Kasting GB, Nitsche JM. A multiphase microscopic diffusion model for stratum corneum permeability. I. Formulation, solution, and illustrative results for representative compounds. J Pharm Sci. 2006;95:620–48.

Wang TF, Kasting GB, Nitsche JM. A multiphase microscopic diffusion model for stratum corneum permeability. II. Estimation of physicochemical parameters, and application to a large permeability database. J Pharm Sci. 2007;96:3024–51.

Weschler CJ, Nazaroff WW. Semivolatile organic compounds in indoor environments. Atmos Environ. 2008;42:9018–40.

Gong M, Zhang Y, Weschler CJ. Predicting dermal absorption of gas-phase chemicals: transient model development, evaluation, and application. Indoor Air. 2014;24:292–306.

Morrison GC, Weschler CJ, Bekö G. Dermal uptake directly from air under transient conditions: advances in modeling and comparisons with experimental results for human subjects. Indoor Air. 2016;26:913–24.

Egawa M, Hirao T, Takahashi M. In vivo estimation of stratum corneum thickness from water concentration profiles obtained with raman spectroscopy. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:4–8.

Rushmer RF, Buettner KJK, Short JM, Odland GF. The skin. Science. 1966;154:343–8.

Cleek RL, Bunge AL. A new method for estimating dermal absorption from chemical exposure. 1. General approach. Pharm Res J Am Assoc Pharm Sci. 1993;10:497–506.

Morrison GC, Weschler CJ, Bekö G. Dermal uptake of phthalates from clothing: comparison of model to human participant results. Indoor Air. 2017;27:642–9.

Weschler CJ, Nazaroff WW. SVOC exposure indoors: fresh look at dermal pathways. Indoor Air. 2012;22:356–77.

Bunge AL, Persichetti JM, Payan JP. Explaining skin permeation of 2-butoxyethanol from neat and aqueous solutions. Int J Pharm. 2012;435:50–62.

Holbrook KA, Odland GF. Regional differences in the thickness (cell layers) of the human stratum corneum: an ultrastructural analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 1974;62:415–22.

Yosipovitch G, Maayan-Metzger A, Merlob P, Sirota L. Skin barrier properties in different body areas in neonates. J Am Acad Pediatr. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.106.1.105.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Center for Research in Energy and the Environment (CREE) of the Missouri University of Science & Technology for their help with the instruments. The modeling component of this research was supported by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation through the Modelling Consortium for Chemistry of Indoor Environments (MOCCIE 1, G-2017–9796 and MOCCIE 2, G-2019-12306).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AE collected data, generated model simulations, drafter and revised the manuscript. GCM conceived of the work, supervised model simulations, revised the manuscript. All authors approved of the final version and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eftekhari, A., Morrison, G.C. Exposure to oxybenzone from sunscreens: daily transdermal uptake estimation. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 33, 283–291 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-021-00383-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-021-00383-9