Abstract

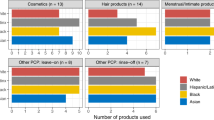

Few studies have characterized life course hair product usage beyond ever/never. We investigated hair product use from childhood to adulthood, usage patterns in adulthood, and socioeconomic status (SES) correlates among African-American (AA) women. Using self-reported data from 1555 AA women enrolled in the Study of Environment, Lifestyle, and Fibroids (2010–2018), we estimated the usage frequency of chemical relaxer/straightener (≥twice/year, once/year, and rarely/never) and leave-in/leave-on conditioner (≥once/week, 1–3 times/month, and rarely/never) during childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Latent class analysis was used to identify patterns of adulthood usage of multiple hair products. SES was compared across latent classes. With a mean age of 33 ± 3.4 years, most women reported ever using chemical relaxers/straighteners (89%), and use ≥twice/year increased from childhood (9%) to adolescence (73%) but decreased in adulthood (29%). Leave-in/leave-on conditioner use followed the same pattern. Each of three identified latent classes reported frequent styling product use and infrequent relaxer/straightener use. Class One was unlikely to use any other products, Class Two moderately used shampoo and conditioner, and Class Three frequently used multiple product types (e.g., moisturizers and conditioners). Participants in the latter two classes reported higher SES. Ever/never characterization may miss important and distinctive patterns of hair product use, which may vary by SES.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 6 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $43.17 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

James-Todd T, Senie R, Terry MB. Racial/ethnic differences in hormonally-active hair product use: a plausible risk factor for health disparities. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14:506–11.

Li ST, Lozano P, Grossman DC, Graham E. Hormone-containing hair product use in prepubertal children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:85–6.

Tiwary CM. A survey of use of hormone/placenta-containing hair preparations by parents and/or children attending pediatric clinics. Mil Med. 1997;162:252–6.

Tiwary CM, Ward JA. Use of hair products containing hormone or placenta by US military personnel. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2003;16:1025–32.

Wu XM, Bennett DH, Ritz B, Cassady DL, Lee K, Hertz-Picciotto I. Usage pattern of personal care products in California households. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:3109–19.

Helm JS, Nishioka M, Brody JG, Rudel RA, Dodson RE. Measurement of endocrine disrupting and asthma-associated chemicals in hair products used by Black women. Environ Res. 2018;165:448–58.

Lewallen R, Francis S, Fisher B, Richards J, Li J, Dawson T, et al. Hair care practices and structural evaluation of scalp and hair shaft parameters in African American and Caucasian women. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14:216–23.

Zota AR, Shamasunder B. The environmental injustice of beauty: framing chemical exposures from beauty products as a health disparities concern. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:418 e411–418 e416.

Johnson TA, Bankhead T. Hair it is: examining the experiences of Black women with natural hair. Open J Soc Sci. 2014;2:86–100.

James-Todd T, Terry MB, Rich-Edwards J, Deierlein A, Senie R. Childhood hair product use and earlier age at menarche in a racially diverse study population: a pilot study. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21:461–5.

McDonald JA, Tehranifar P, Flom JD, Terry MB, James-Todd T. Hair product use, age at menarche and mammographic breast density in multiethnic urban women. Environ Health. 2018;17:1.

Wise LA, Palmer JR, Reich D, Cozier YC, Rosenberg L. Hair relaxer use and risk of uterine leiomyomata in African-American women. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:432–40.

Giulivo M, Lopez de Alda M, Capri E, Barcelo D. Human exposure to endocrine disrupting compounds: Their role in reproductive systems, metabolic syndrome and breast cancer. A review. Environ Res. 2016;151:251–64.

De Coster S, van Larebeke N. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: associated disorders and mechanisms of action. J Environ public health. 2012;2012:713696.

Cesario SK, Hughes LA. Precocious puberty: a comprehensive review of literature. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36:263–74.

Llanos AAM, Rabkin A, Bandera EV, Zirpoli G, Gonzalez BD, Xing CY, et al. Hair product use and breast cancer risk among African American and White women. Carcinogenesis. 2017;38:883–92.

Jiang C, Hou Q, Huang Y, Ye J, Qin X, Zhang Y, et al. The effect of pre-pregnancy hair dye exposure on infant birth weight: a nested case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:144.

Ahn C, McMichael A, Smith P. The impact of hair care practices and attitudes toward hair management on exercise habits in African American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:Ab93–Ab93.

Ahn CS, Suchonwanit P, Foy CG, Smith P, McMichael AJ. Hair and Scalp Care in African American Women Who Exercise. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:579–80.

Bowen F, O’Brien-Richardson P. Cultural hair practices, physical activity, and obesity among urban African-American girls. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2017;29:754–62.

Eyler AE, Wilcox S, Matson-Koffman D, Evenson KR, Sanderson B, Thompson J, et al. Correlates of physical activity among women from diverse racial/ethnic groups. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11:239–53.

Hall RR, Francis S, Whitt-Glover M, Loftin-Bell K, Swett K, McMichael AJ. Hair care practices as a barrier to physical activity in African American women. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:310–4.

Harley AE, Odoms-Young A, Beard B, Katz ML, Heaney CA. African American social and cultural contexts and physical activity: strategies for navigating challenges to participation. Women Health. 2009;49:84–100.

Huebschmann AG, Campbell LJ, Brown CS, Dunn AL. “My hair or my health:” overcoming barriers to physical activity in African American women with a focus on hairstyle-related factors. Women Health. 2016;56:428–47.

Im EO, Ko Y, Hwang H, Yoo KH, Chee W, Stuifbergen A, et al. “Physical activity as a luxury”: African American women’s attitudes toward physical activity. West J Nurs Res. 2012;34:317–39.

Joseph RP, Ainsworth BE, Keller C, Dodgson JE. Barriers to physical activity among African American women: an integrative review of the literature. Women Health. 2015;55:679–99.

Joseph RP, Coe K, Ainsworth BE, Hooker SP, Mathis L, Keller C. Hair as a barrier to physical activity among African American women: a qualitative exploration. Front Public Health. 2017;5:367.

Pekmezi D, Marcus B, Meneses K, Baskin ML, Ard JD, Martin MY, et al. Developing an intervention to address physical activity barriers for African-American women in the deep south (USA). Womens Health. 2013;9:301–12.

Taylor WC, Yancey AK, Leslie J, Murray NG, Cummings SS, Sharkey SA, et al. Physical activity among African American and Latino middle school girls: consistent beliefs, expectations, and experiences across two sites. Women health. 1999;30:67–82.

Versey HS. Centering perspectives on Black women, hair politics, and physical activity. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:810–5.

Walker SD. Perceptions of barriers that inhibit African American women and adolescent girls from participation in physical activity. Las Vegas, US: Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), University of Nevada; 2012.

Barnes AS, Goodrick GK, Pavlik V, Markesino J, Laws DY, Taylor WC. Weight loss maintenance in African-American women: focus group results and questionnaire development. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:915–22.

Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS data brief no. 288. Hyattesville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2017.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, Fryar CD, Kruszon-Moran D, Kit BK, et al. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988–94 through 2013–4. JAMA. 2016;315:2292–9.

Taylor KW, Baird DD, Herring AH, Engel LS, Nichols HB, Sandler DP, et al. Associations among personal care product use patterns and exogenous hormone use in the NIEHS Sister Study. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2017;27:458–64.

Taylor KW, Troester MA, Herring AH, Engel LS, Nichols HB, Sandler DP, et al. Associations between personal care product use patterns and breast cancer risk among White and Black women in the sister study. Environ Health Perspect. 2018;126:027011.

James-Todd T, Stahlhut R, Meeker JD, Powell SG, Hauser R, Huang T, et al. Urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations and diabetes among women in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2001–8. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:1307–13.

Baird DD, Harmon QE, Upson K, Moore KR, Barker-Cummings C, Baker S, et al. A prospective, ultrasound-based study to evaluate risk factors for uterine fibroid incidence and growth: methods and results of recruitment. J Womens Health. 2015;24:907–15.

Goodman LA. Exploratory latent structure-analysis using both identifiable and unidentifiable models. Biometrika. 1974;61:215–31.

Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Struct Equ Modeling. 2001;8:430–57.

Lanza ST, Collins LM, Lemmon DR, Schafer JL, PROC LCA, SAS A. Procedure for latent class analysis. Struct Equ Modeling. 2007;14:671–94.

Nasserinejad K, van Rosmalen J, de Kort W, Lesaffre E. Comparison of criteria for choosing the number of classes in Bayesian finite mixture models. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0168838.

Oberski D. Mixture models: latent profile and latent class analysis. In: Robertson J, Kaptein M, editors. Modern Statistical Methods for HCI. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016, p. 275–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26633-6_12.

Goodman LA. On the assignment of individuals to latent classes. Socio Methodol. 2007;37:1–22.

Teteh DK, Montgomery SB, Monice S, Stiel L, Clark PY, Mitchell E. My crown and glory: Community, identity, culture, and Black women’s concerns of hair product-related breast cancer risk. Cogent Art Humanities. 2017;4:17.

Rosenberg L, Wise LA, Palmer JR. Hair-relaxer use and risk of preterm birth among African-American women. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:768–72.

Blackmore-Prince C, Harlow SD, Gargiullo P, Lee MA, Savitz DA. Chemical hair treatments and adverse pregnancy outcome among Black women in central North Carolina. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:712–6.

Omosigho UR. Changing practices of hair relaxer use among black women in the United States. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:e4–e5.

James-Todd TM, Chiu Y-H, Zota AR. Racial/ethnic disparities in environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals and women’s reproductive health outcomes: epidemiological examples across the life course. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2016;3:161–80.

James-Todd TM, Meeker JD, Huang T, Hauser R, Seely EW, Ferguson KK, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in phthalate metabolite concentration changes across full-term pregnancies. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2017;27:160–6.

Ruiz D, Becerra M, Jagai JS, Ard K, Sargis RM. Disparities in environmental exposures to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and diabetes risk in vulnerable populations. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:193–205.

Jackson JS, Knight KM, Rafferty JA. Race and unhealthy behaviors: chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:933–9.

Jackson JW, Williams DR, VanderWeele TJ. Disparities at the intersection of marginalized groups. Soc psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:1349–59.

Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:404–16.

Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J. Collins C Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann New Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:69–101.

Bray BC, Lanza ST, Tan X. Eliminating bias in classify-analyze approaches for latent class analysis. Struct Equ Modeling. 2015;22:1–11.

Jenkins F, Jenkins C, Gregoski MJ, Magwood GS. Interventions promoting physical activity in African American women: an integrative review. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017;32:22–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Study of Environment, Lifestyle, and Fibroids participants and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences library staff, Stacy Mantooth and Erin Knight, for assistance with the literature search.

Funding

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Z1AES103325-01 [CLJ] and 1ZIAES049013-23 [DB]).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: SAG, QH, DB, and CLJ. Acquisition of data: DB. Statistical analysis: SAG. Interpretation of data: SAG, TJ-T, QH, KWT, DB, and CLJ. Drafting of the paper: SAG. Critical revision of the paper for important intellectual content: SAG, TJ-T, QH, KWT, DB, and CLJ. Administrative, technical, and material support: QH, DB, and CLJ. Obtaining funding and study supervision: DB and CLJ. Final approval: SAG, TJ-T, QH, KWT, DB, and CLJ.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gaston, S.A., James-Todd, T., Harmon, Q. et al. Chemical/straightening and other hair product usage during childhood, adolescence, and adulthood among African-American women: potential implications for health. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 30, 86–96 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-019-0186-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-019-0186-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Differences in personal care product use by race/ethnicity among women in California: implications for chemical exposures

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology (2023)

-

The Importance of Addressing Early-Life Environmental Exposures in Cancer Epidemiology

Current Epidemiology Reports (2022)

-

Acculturation and endocrine disrupting chemical-associated personal care product use among US-based foreign-born Chinese women of reproductive age

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology (2021)

-

Correlates of urinary concentrations of phthalate and phthalate alternative metabolites among reproductive-aged Black women from Detroit, Michigan

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology (2021)

-

Hormonal activity in commonly used Black hair care products: evaluating hormone disruption as a plausible contribution to health disparities

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology (2021)