Abstract

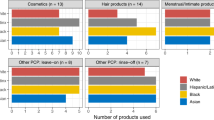

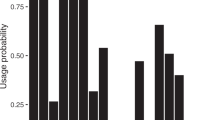

Some chemicals used in personal care products (PCPs) are associated with endocrine disruption, developmental abnormalities, and reproductive impairment. Previous studies have evaluated product use among various populations; however, information on college women, a population with a unique lifestyle, is scarce. The proportion and frequency of product use were measured using a self-administered survey among 138 female undergraduates. Respondents were predominately Caucasian (80.4%, reflecting the college’s student body), and represented all years of study (freshman: 24.6%; sophomore: 30.4%; junior: 18.8%; senior: 26.1%). All respondents reported use of at least two PCPs within 24 h prior to sampling (maximum = 17; median = 8; IQR = 6–11). Compared with studies of pregnant and postpartum women, adult men, and Latina adolescents, college women surveyed reported significantly higher use of deodorant, conditioner, perfume, liquid soap, hand/body lotion, sunscreen, nail polish, eyeshadow, and lip balm (Chi Square, p < 0.05). More study is needed to understand the magnitude and racial disparities of PCP chemical exposure, but given the potential effects on reproduction and fertility, our findings of abundant and frequent product use among these reproductive-aged women highlight opportunities for intervention and information on endocrine disrupting chemical (EDC)-free alternative products and behaviors.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 6 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $43.17 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

08 April 2020

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-020-0221-7

References

De Coster S, van Larebeke N. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: associated disorders and mechanisms of action. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:713696.

Darbre PD, Aljarrah A, Miller WR, Coldham NG, Sauer MJ, Pope GS. Concentrations of parabens in human breast tumours. J Appl Toxicol. 2004;24:5–13.

Rachoń D. Endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) and female cancer: informing the patients. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2015;16:359–64.

Dodson RE, Nishioka M, Standley LJ, Perovich LJ, Brody JG, Rudel RA. Endocrine disruptors and asthma-associated chemicals in consumer products. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:935–43.

Juhász MLW, Marmur ES. A review of selected chemical additives in cosmetic products. Dermatologic Ther. 2014;27:317–22.

Koniecki D, Wang R, Moody RP, Zhu J. Phthalates in cosmetic and personal care products: concentrations and possible dermal exposure. Environ Res. 2011;111:329–36.

Guo Y, Kannan K. A survey of phthalates and parabens in personal care products from the United States and its implications for human exposure. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:14442–9.

Liao C, Kannan K. A survey of alkylphenols, bisphenols, and triclosan in personal care products from China and the United States. Archives of environmental contamination. Toxicology. 2014;67:50–9.

Liao C, Kannan K. Widespread occurrence of benzophenone-type UV light filters in personal care products from china and the United States: an assessment of human Exposure. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48:4103–9.

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Toxicological profile for diethyl phthalate. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 1995.

Weatherly LM, Gosse JA. Triclosan exposure, transformation, and human health effects. J Toxicol Environ Health Part B, Crit Rev. 2017;20:447–69.

Berger KP, Kogut KR, Bradman A, She J, Gavin Q, Zahedi R, et al. Personal care product use as a predictor of urinary concentrations of certain phthalates, parabens, and phenols in the HERMOSA study. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2018;1:21–32.

Braun JM, Just AC, Williams PL, Smith KW, Calafat AM, Hauser R. Personal care product use and urinary phthalate metabolite and paraben concentrations during pregnancy among women from a fertility clinic. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2014;24:459–66.

Parlett LE, Calafat AM, Swan SH. Women’s exposure to phthalates in relation to use of personal care products. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2013;23:197.

Wu X, Bennett DH, Ritz B, Cassady DL, Lee K, Hertz-Picciotto I. Usage pattern of personal care products in California households. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:3109–19.

Manová E, von Goetz N, Keller C, Siegrist M, Hungerbühler K. Use patterns of leave-on personal care products among Swiss–German children, adolescents, and adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:2778–98.

Biesterbos JWH, Dudzina T, Delmaar CJE, Bakker MI, Russel FGM, von Goetz N, et al. Usage patterns of personal care products: Important factors for exposure assessment. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;55:8–17.

Pelletier JE, Laska MN. Balancing healthy meals and busy lives: associations between work, school, and family responsibilities and perceived time constraints among young adults. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44:481–9.

Deliens T, Clarys P, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Deforche B. Determinants of eating behaviour in university students: a qualitative study using focus group discussions. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:53–65.

Chan LM, Chalupka SM, Barrett R. Female college student awareness of exposures to environmental toxins in personal care products and their effect on preconception health. Workplace Health Saf. 2015;63:64–70.

Presser S, Rothgeb JM, Couper MP, Lessler JT, Martin E, Martin J, et al. Methods for Testing and Evaluating Survey Questionnaires. 1. Aufl. ed. US: Wiley-Interscience; 2004.

Willis G. Cognitive interviewing: a tool for improving questionnaire design. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Inc; 2004.

Beatty PC, Willis GB. Research synthesis: the practice of cognitive interviewing. Public Opin Q. 2007;71:287–311.

Nassan FL, Coull BA, Gaskins AJ, Williams MA, Skakkebaek NE, Ford JB, et al. Personal care product use in men and urinary concentrations of select phthalate metabolites and parabens: results from the Environment And Reproductive Health (EARTH) Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125:087012.

Souiden N, Diagne M. Canadian and French men’s consumption of cosmetics: a comparison of their attitudes and motivations. J Consum Mark. 2009;26:97–109.

Weber JM, Capitant de Villebonne J. Differences in purchase behavior between France and the USA: the cosmetic industry. J Fash Mark Manag: Int J. 2002;6:396–407.

College of Charleston Institutional Research, Planning, and Information Management. Spring 2019 Statistics [Internet]. 2019 [cited 08 April 2019]. Available from: http://irp.cofc.edu/docs/census-data/Census2_Spring2019.pdf.

Li ST, Lozano P, Grossman DC, Graham E. Hormone-containing hair product use in prepubertal children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:85–6.

James-Todd T, Senie R, Terry MB. Racial/ethnic differences in hormonally-active hair product use: a plausible risk factor for health disparities. J Immigr Minority Health. 2012;14:506–11.

Philippat C, Bennett D, Calafat AM, Picciotto IH. Exposure to select phthalates and phenols through use of personal care products among Californian adults and their children. Environ Res. 2015;140(Jul):369–76.

Bell FP. Effects of phthalate esters on lipid metabolism in various tissues, cells and organelles in mammals. Environ Health Perspect. 1982;45:41–50.

Latini G, Verrotti A, De Felice C. DI-2-ethylhexyl phthalate and endocrine disruption: a review. Curr Drug Targets Immune, Endocr Metab Disord. 2004;4:37–40.

Meeker JD, Sathyanarayana S, Swan SH. Phthalates and other additives in plastics: human exposure and associated health outcomes. Philos Trans R Soc B: Biol Sci. 2009;364:2097–113.

Mathieu-Denoncourt J, Wallace SJ, de Solla SR, Langlois VS. Plasticizer endocrine disruption: highlighting developmental and reproductive effects in mammals and non-mammalian aquatic species. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2014;219:74–88.

Swan SH. Environmental phthalate exposure in relation to reproductive outcomes and other health endpoints in humans. Environ Res. 2008;108:177–84.

Dann AB, Hontela A. Triclosan: environmental exposure, toxicity and mechanisms of action. J Appl Toxicol. 2011;31:285–311.

Wang C, Tian Y. Reproductive endocrine-disrupting effects of triclosan: population exposure, present evidence and potential mechanisms. Environ Pollut. 2015;206:195–201.

Vélez MP, Arbuckle TE, Fraser WD. Female exposure to phenols and phthalates and time to pregnancy: the Maternal-Infant Research on Environmental Chemicals (MIREC) study. Fertil Steril 2015;103:1020.e2.

Wang X, Chen X, Feng X, Chang F, Chen M, Xia Y, et al. Triclosan causes spontaneous abortion accompanied by decline of estrogen sulfotransferase activity in humans and mice. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18252.

Dinwiddie MT, Terry PD, Chen J. Recent evidence regarding triclosan and cancer risk. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:2209–17.

Koeppe ES, Ferguson KK, Colacino JA, Meeker JD. Relationship between urinary triclosan and paraben concentrations and serum thyroid measures in NHANES 2007–8. Sci Total Environ. 2013;445–6:299–305.

Smarr MM, Sundaram R, Honda M, Kannan K, Louis GM. Urinary concentrations of parabens and other antimicrobial chemicals and their association with couples’ fecundity. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;125:730–6.

Fuhrman VF, Tal A, Arnon S Why endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) challenge traditional risk assessment and how to respond. J Hazard Mater. 2015;286:589–611.

Gentina E, Palan KM, Fosse‐Gomez MH. The practice of using makeup: a consumption ritual of adolescent girls. J Consum Behav. 2012;11(Mar):115–23.

Marcoux D. Appearance, cosmetics, and body art in adolescents. Dermatologic Clin. 2000;18(Oct):667–73.

Lang C, Fisher M, Neisa A, MacKinnon L, Kuchta S, MacPherson S, et al. Personal care product use in pregnancy and the postpartum period: implications for exposure assessment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:105.

Marie C, Cabut S, Vendittelli F, Sauvant-Rochat M. Changesin cosmetics use during pregnancy and risk perception by women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:383.

Romero-Franco M, Hernández-Ramírez RU, Calafat AM, Cebrián ME, Needham LL, Teitelbaum S, et al. Personal care product use and urinary levels of phthalate metabolites in Mexican women. Environ Int. 2011;37:867–71.

Sandanger TM, Huber S, Moe MK, Braathen T, Leknes H, Lund E. Plasma concentrations of parabens in postmenopausal women and self-reported use of personal care products: the NOWAC postgenome study. J Exposure Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2011;21:595–600.

Garcia-Hidalgo E, von Goetz N, Siegrist M, Hungerbühler K. Use-patterns of personal care and household cleaning products in Switzerland. Food Chem Toxicol. 2017;99:24–39.

Kim S, Tanner A, Friedman DB, Foster C, Bergeron C. Barriers to clinical trial participation: comparing perceptions and knowledge of African American and white South Carolinians. J Health Commun. 2015;20:816–26.

Barrett NJ, Ingraham KL, Vann Hawkins T, Moorman PG. Engaging African Americans in research: the recruiter’s perspective. Ethnicity Dis. 2017;27:453–62.

Comiskey D, Api AM, Barrett C, Ellis G, McNamara C, O’Mahony C, et al. Integrating habits and practices data for soaps, cosmetics and air care products into an existing aggregate exposure model. Regulatory Toxicol Pharmacol. 2017;88:144–56.

Harley KG, Kogut K, Madrigal DS, Cardenas M, Vera IA, Meza-Alfaro G, et al. Reducing phthalate, paraben, and phenol exposure from personal care products in adolescent girls: findings from the HERMOSA Intervention Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124(Oct):1600.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the contributions of faculty and students from the College of Charleston’s Women’s Health Research Team. Faculty members and student research assistants were integral in vetting project ideas, conducting a literature review, improving survey design and execution, and recruiting study participants. We also thank the staff at the College of Charleston’s Student Health Services for use of their space during data collection. Funding for this study was provided by the College of Charleston’s Major Academic Year Support (MAYS) Research Grant (MA2017-006), as well as research and development funds from the College of Charleston’s Department of Health and Human Performance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hart, L.B., Walker, J., Beckingham, B. et al. A characterization of personal care product use among undergraduate female college students in South Carolina, USA. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 30, 97–106 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-019-0170-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-019-0170-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The Importance of Addressing Early-Life Environmental Exposures in Cancer Epidemiology

Current Epidemiology Reports (2022)