Abstract

Background and objective

The association between physical activity and diet has a valuable impact in weight status management to counteract obesity. In this context, within different training strategies (i.e., endurance, resistance training, concurrent training, agility training) the Integrative Neuromuscular Training (INT) represents a structured training mode focused on global human movement pattern development with the aim to enhance motor control, mobility and stability. In this narrative review we aimed to discuss the feasibility of INT interventions on physical fitness and body composition outcomes in individuals with obesity.

Subjects

Medline/PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Google Scholar including were searched before 1st February 2023 without restrictions on publication year.

Methods

Two researchers extracted data from published trials. Randomized controlled trials or clinical trials, Body Mass Index of children and adolescents at the 95% percentile or greater, and for adults to be above 30 kg/m2, detailed intervention description, randomization process and allocation into an experimental or a control group, trials must have been written in English, were included.

Results

We included a total of 19 studies complying with the inclusion criteria for the review process. There is evidence that INT promotes positive adaptations in fitness levels in both younger and older participants with concomitant ameliorations during a shorter, medium and longer time period. Moreover, cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength, balance, postural control and body composition reached significant remarkable improvements following a specific intervention based on INT principles compared to other training mode. However, Body Mass Index, fat mass percentage and waist circumference showed similar changes overtime.

Conclusions

Taken together, these findings support the effectiveness of INT in ameliorating physical fitness (i.e., health-related and skill related components) without negative changes in body composition. Nevertheless, fitness coaches and therapists may consider this training modality a feasible option when prescribing physical exercise in outpatients with obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity represents a remarkable health metabolic disease characterized by an increased body fat that could lead to an augmented risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and mortality [1, 2]. An adequate nutrition strategy, psychological-behavioral support as well as physical activity represent key factors in weight status management [3, 4]. Several international guidelines, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommend to respect an amount of 150–250 min per week of moderate-intensity physical activity to obtain a significant weight loss [5,6,7].

In this context, physical fitness refers to the body’s ability to perform daily-life activities efficiently, which is determined by different components, including “health-related” factors, such as cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength and endurance, flexibility, and “skill-related” variables as agility, motor coordination, balance, power, reaction time and speed [7, 8].

Cardiorespiratory fitness can be improved through various form of continuous or intermittent exercises with the aim to improve cardiorespiratory function [6, 9]. For people with obesity, it is particularly suggested to observe an exercise intensity between 49% and 85% of peak aerobic capacity to induce several modifications in visceral adipose tissue [10] and body fat reduction [11].

For what concern muscular strength, the purpose is to increase skeletal muscle mass involving major muscle groups [7]. Strength training for obesity might be helpful to improve myogenesis, lean mass and protein synthesis, characteristics particularly suited to counteract sarcopenic obesity [12]. Additionally, the combination between aerobic and strength training modalities (known as Concurrent Training) seems to be effective in improving body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness and muscular strength [11, 13] with little interference on muscle size growth [14]. Individual with obesity may also obtain other positive effects by following a dietary restriction program [11, 15].

For flexibility, obesity may impair joint range of motion because the adipose tissue interposed around each joint may limit segmental body rotation, causing mechanical interference [16], especially in elbow, hip and knee segments [17].

Lastly, when dealing with skill-related components of physical fitness, especially balance and motor coordination, individuals with obesity exhibit a reduced medio-lateral or sagittal stability and motor coordination with a concomitant center of pressure anteriorly shifted, due to compensatory motions counteracting body weight accumulation [18, 19].

Traditionally, all of these physical fitness’ components can be improved through specific movements or exercises targeting a single specific outcome (i.e., aerobic, strength, balance, flexibility) in an isolated mode during an entire training session.

An innovative training regimen that embraces the interaction between all of each component is called Integrative Neuromuscular Training (INT) [20]. This modality can be a suitable option to target the overall physical fitness (health and skill-related variables) in an integrated manner. INT is a training approach targeted on global human movement pattern development (e.g., fundamental movement skills) and specific strength and conditioning exercises (e.g., motor control, mobility, strength, proprioception, cardiorespiratory fitness), with the aim to restore a correct movement mechanics by stressing an efficient quality of movement and physical fitness [21, 22].

Following INT principles, improvements in muscular strength, power, motor skill performance, dynamic stability and balance [21, 23] were observed in children and adolescents [24,25,26]. Additionally there is an enhancement in motor competence and proficiency [27], as well as a reduction in movement asymmetries and “motor awkwardness”[28]. Moreover, a recent systematic review reported that INT is an effective training mode to improve motor performance and injury prevention especially in young athletes [29]. Taken together, these findings provide evidence supporting INT as a training mode to target the overall physical fitness by focusing on the quality of movement.

To the best of the Authors’ knowledge, the existing literature regarding the effectiveness of INT on individuals with a noteworthy health condition (i.e., obesity) is scarce. However, from a theoretical point of view, INT could be helpful for ameliorating fitness levels in people with obesity thanks to a mixture of stimuli within the same training session.

Therefore, the aim of this narrative review was to identify and synthesize the feasibility of INT intervention on health-related, skill-related and body composition outcomes in individuals with obesity.

Methods

Data sources and searches

This narrative review was structured with a computerized search of four electronic databases (Medline/PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Google Scholar) including articles published before 1st February 2023 without restrictions on publication year. Articles were limited to human experiments. The search used a combination of the following terms “integrative neuromuscular training” OR “integrative neuromuscular exercise” OR “integrative neuromotor training” OR “integrative neuromotor exercise” OR “neuromotor training” OR “neuromotor exercise” OR “neuromuscular training” OR “neuromuscular exercise” OR “balance training” OR “balance exercise” OR “proprioception training” OR “proprioception exercise” OR “postural control” OR “postural stability” OR “cognitive training” OR “functional training” OR “functional movement” OR “quality of movement” OR “movement quality” AND “obes*“.

Study selection

In order to exclude duplicate studies, two authors (L.C. and D.F.) reviewed the abstracts of each study respecting the following inclusion criteria: a) randomized controlled trials or clinical trials, b) Body Mass Index (BMI) of children and adolescents at the 95% percentile or greater, and for adults to be above 30 kg/m2, c) detailed intervention description (an health-related component associated with, at least, one skill-related outcome), d) randomization process and allocation into an experimental or a control group, e) trials must have been written in English and published in a peer-reviewed journal. Studies with participants with severe cardiovascular, neurological or physical comorbidities, co-intervention (psychological or medical support) or duration less than 3 weeks were excluded.

Data extraction

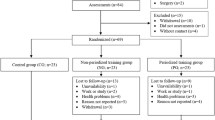

Two authors (L.C., D.F.) independently screened the articles by using title and abstracts. Abstracts were excluded based on the exclusion criteria. Next, from the initial list, the full text of the selected articles was screened by those two authors to verify whether they met the inclusion criteria excluding duplicate studies. Finally, they compiled a list of all eligible articles for this review. It is worth emphasizing that the participants’ ages, gender, race/ethnicity, etc., were not restricted in order to obtain a more complete understanding of this topic. The studies were considered when a consensus was reached by two authors (L.C., D.F.) for a later presentation and discussion. If in presence of a disagreement between these two authors, a third researcher (L.G.) made the definitive decision.

Results

The review procedure generated 147 papers from three electronic databases and after an initial removal before screening (e.g., duplicate articles), a total of 19 studies complying with the inclusion criteria were considered eligible for the review process. The overall number of participants was 828, with an age range from 7 to 70 years with a comprehensive intervention’s duration that ranges from three weeks up to twelve months (Table 1).

The main finding of this narrative review was that INT intervention is effective to improve both health-related and skill-related fitness components in individuals with obesity, independently from training duration and participants’ age. On one hand, balance, postural control, and movement competence appear to be better improved by INT than a traditional training regimen. On the other hand, body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness exhibited similar enhancements compared to a common intervention. In addition, it seems that motor adaptations obtained by INT were slightly preserved during a subsequent detraining period.

Discussion

Study population: younger versus older individuals

INT appears to be effective in ameliorating postural control in children and adolescents with obesity ranging from seven to sixteen years old (N = 5 studies). In this regards, seven-year-old children demonstrated significant changes in Center of Pressure variables (i.e., sway area, mean velocity, antero-posterior velocity, medio-lateral velocity) and dynamic balance score measured with the Star Excursion Balance Test following a training program focused on INT approach (e.g., mini hurdle jumping, agility cone drills, single-leg balance, marching in place, single-leg squat) [30]. Similarly, Molina-Garcia and colleagues demonstrated that 10-year-old participants who followed a movement-quality exercise intervention composed of exercise to improve awareness of movement pattern, mobility, stability and strength combined with multi-games exercises, significantly improved their posture in various body segments (e.g., lower limb angle and plumb-tragus distance), functional performance in the deep squat and active leg raise patterns, as well as maximum forefoot force support, while maintaining their foot and pelvic alignment during the walking pattern when compared to a conventional lifestyle intervention [31,32,33]. Conversely, in adolescents (age range from 13 to 16 years), an INT intervention composed of a goal-directed activity (e.g., throwing at targets, emptying boxes, walking, running) and team-based games compared to a video games program using Nintendo Wii gaming system induced similar ameliorations in muscular strength and in both aerobic and anaerobic fitness profile without between-groups differences [34].

Although this type of training has been developed especially for a younger population with the aim to minimize the injury risk during sport activities, thanks to a better movement symmetry and “motor awkwardness” [23, 28, 35], there is a plethora of studies that demonstrated the effectiveness of INT also in adulthood by enhancing both health and skill-related physical fitness components. Moreover, INT improved also cognitive and psychological performance (e.g., selective attention, cognitive flexibility, motivation, self-efficacy, vitality, enjoyment) with contrasting results on body weight change or fat mass reduction [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49].

Duration of intervention: short and long-time training effects outcomes

INT training mode induced significant adaptation responses overtime ranging from a short, to a mid-long-time period people with obesity. In two studies, a 3-week training duration was sufficient to improve cardiorespiratory fitness, respiratory muscles strength, quality of life and postural stability [41, 46]. In this regard, Bezzoli et al., tested the efficacy of a 3-weeks multidisciplinary rehabilitation program composed by one daily 30-min conditioning session on a bike ergometer (intensity of 60–70% heart rate maximum) combined with motor control exercises and rib cage mobility. The Authors demonstrated significant improvements in pulmonary function (Forced Vital Capacity, Maximal Voluntary Ventilation, Maximal Expiratory Pressure), quality of life (Patient Specific Function Scale) and cardiorespiratory fitness (6 minute walking test) [41]. On the same line of evidence, also Maffiuletti and colleagues showed that a short-time intervention period (3 weeks) targeting body weight reduction strategies as energy restricted diet, psychological counseling and physical activity combined with balance and proprioceptive exercises improved trunk postural sway and time of balance maintenance in individuals with obesity [46]. Similarly, Guzmán-Muñoz et al. showed that a 4-week training program based on neuromuscular stimuli (e.g., mini hurdle jumping, agility drills, single-leg balance, marching in place, tandem walk, and single-leg squat) enhanced static (e.g., mean velocity and sway area center of pressure) and dynamic postural variables (e.g., maximal anterior, postero-lateral and postero-medial reach distances during a monopodalic stance) [30]. A period with the same duration appeared to be effective in ameliorating body balance detected through the single leg test and the Star Excursion Balance Test following a specific training protocol (4 week/sessions for 45 min) conducted with adult individuals who were treated with a sleeve gastrectomy [47].

For what concern mid-time effects ranging from six to fourteen weeks of intervention duration, there is evidence promoting positive effects on physical fitness outcomes (i.e., muscular strength, body balance, flexibility, cardiorespiratory fitness) and negligeable changes in anthropometry and body composition both in adults [42, 44] and adolescents [31,32,33,34].

Lastly, when dealing with long-time interventions, Batrakoulis et al. demonstrated that an INT program conducted over 10 months was able to increase daily energy expenditure, reduce fat mass, improvement muscular strength and cardiovascular performance in forty-nine individuals with obesity [37]. The same research group highlighted that a progressive INT based protocol (e.g., squat, hinge, lunge, push, pull, carry, rotation, plank exercises) using portable tools (e.g., suspension, belts, balance balls, kettlebells, medicine balls, battle ropes, stability balls, speed ladders, foam rollers, elastic bands) preserved muscular strength, aerobic fitness, flexibility, bone mineral density and psychological regulation (e.g., wellbeing, vitality) in inactive females with obesity [39, 40]. Moreover, positive findings were also detected following eighteen weeks of weight loss combined with an INT program in obese elderly adults, promoting significant improvements in physical function tested via Short Physical Performance Battery, abdominal visceral (VAT) and thigh intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT), when compared to individuals who followed a traditional physical activity program combined with educational lifestyle workshops [49]. Finally, La Scala Teixeira et al. demonstrated that an INT protocol with a duration of 30 weeks improved cardiorespiratory fitness, whereas controversial changes in fat mass, body weight and lean mass were found. However, waist circumference showed a significant reduction overtime when compared to other training interventions (e.g., interdisciplinary therapy and interdisciplinary education) [45].

Cardiorespiratory fitness outcome

Cardiorespiratory fitness was investigated in six studies [33, 34, 37, 41, 45, 48] reporting significant improvements following a specific neuromuscular training protocol. Batrakoulis and colleagues (2018) showed positive changes in VO2max from baseline (26.1 ± 4.4 mL/kg/min) to post-training (33.1 ± 4.8 mL/kg/min; p < 0.001) following a INT protocol (e.g., high-intensity whole-body multi-joint movements in a circuit training modality respecting a heart rate maximum major of 65%) with a concomitant significant reduction in blood lactate concentration during the entire training phase (i.e., from week one to week forty) [37]. On the same line of evidence also Bezzoli et al., reported significant improvements in distance covered during the six-minute walking test (403.4 ± 158.4 m pre-training versus 464.6 ± 131.6 m post-training) in obese individuals who performed neuromotor exercises combined with conditioning sessions performed at 60–70% of their maximum heart rate [41]. Notably, also La Scala Teixeira and colleagues observed a significant main effect of time on VO2max (F = 12.441, p = 0.001) in individuals who performed different functional training circuits composed by free weights, elastic bands and bodyweight movements (e.g., upright row with sumo squat, dumbbell fly with pelvic elevation, elastic trunk rotation, front raise with side lunge, suspended row, knee flexion with elbow flexion, trunk lateral flexion, single leg balance with eyes closed) (p = 0.014) [45]. Conversely, three studies did not observe between-group changes in this specific outcome following a INT program [33, 34, 48].

Muscular strength outcome

Concerning the effects of INT on muscular strength, five out of seven studies reported significant improvements. Specifically, the upper and lower-body strength assessed with different procedures (e.g., one repetition maximum in vertical chest press, one repetition maximum in supinated lat pull-down, one repetition maximum in arm press, isometric handgrip strength test, one repetition maximum in horizontal leg press, one repetition maximum in seated leg extension, one repetition maximum in leg curl, sit to stand test, standing long jump test, isometric knee extensor test, isometric ankle plantar-flexors and dorsi-flexor test) showed positive changes in individuals with obesity in favor to an INT approach [33, 37, 38, 40, 42]. Two studies [34, 48] found similar improvements overtime without differences between training interventions (INT protocol versus control) for both upper and lower-body segments. On one hand, it could be speculated that these controversial results might be due to a reduced adherence to the training program, or to the equipment used (e.g., elastic bands, dumbbells, suspension belts, kettlebells, medicine balls, battle ropes), but on the other hand the duration of each training program (e.g., from eight weeks to ten months) induced a better movement pattern learning and muscle recruitment leading to positive changes in muscular strength [50, 51].

Flexibility outcome

In three studies, joint range of motion showed significant changes between groups [38, 40, 48]. In detail, Batrakoulis et al. demonstrated remarkable variations (p < 0.001) in sit and reach test and in glenohumeral internal rotation in favor to INT group respect to control group. For what concern ankle dorsi-flexion and shoulder extension test there is trend in reaching a significant difference (p = 0.057) [40]. Moreover, the same research group demonstrated that an INT program performed with a different frequency (e.g., one day/week, two days/week, or three days/week) was able to induce significant improvements compared to what observed in the control group (p = 0.025) [38]. Specifically, one day/week was more effective to ameliorate ankle dorsiflexion and shoulder flexion; two days/week induced significant ameliorations in passive range of motion in ankle dorsiflexion, hip flexion and shoulder flexion. Finally, three days/week promoted a better flexibility (p < 0.001) in ankle dorsiflexion, knee flexion, hip flexion and shoulder flexion [38]. Lastly, the study by Cambiriba and colleagues found that the flexibility detected through the Wells bench test reached similar changes in the experimental group who followed a training protocol focused on INT principles when compared to control group [48].

Body balance, postural control, and functional performance outcomes

Several studies have reported positive changes in both static [42, 46, 47] and dynamic balance [30, 47], measured in different stances, after a period of INT, underlying the importance of a neuromuscolar training for stimulating proprio and exteroception in individuals with obesity. On the same line of evidence, the center of pressure sway area and velocity [30], combined the maximum force sustained by the medio-lateral forefoot, the lower limb angle, pelvic tilt and the plumb-tragus alignment significantly improved (p < 0.05) thanks to neuromotor exercises whose aim was to preserve an optimal spine position, self-awareness of movement patterns, core muscles stabilization and muscular strength [31, 33]. Functional performance has also been shown to improve with INT intervention, with five studies reporting a significant increase in the Functional Movement Screen total score [38, 39, 42] and single scores in the Hurdle Step (p = 0.0036), Active Straight Leg Raise (p = 0.0003) and Deep Squat (p = 0.004) movement patterns [32, 42]. Moreover, also Santanasto and colleagues demonstrated a significant amelioration in functional capacity after an INT protocol using the Short Physical Performance Battery, with scores increasing from 9.7 at baseline to 10.3 arbitrary units at the end of the intervention period in older people with obesity [49]. Taken together, all these findings provides evidence that individuals with obesity may benefit from an INT protocol focused on motor control, articular stability and movement competence in ameliorating their body balance and postural control.

Cognitive performance outcome

Regarding the effects of INT on cognition, three studies showed beneficial adaptations on cognitive and psychological performances [36, 39]. In detail, psychological distress scores detected using a specific questionnaire (i.e., General Health Questionnaire -12) significantly decreased by 68%, vitality score increased by 53% (p = 0.001) and finally also the introjected regulation, intrinsic regulation and identified regulation significantly improved throughout the five-month period (p = 0.001; p = 0.004, p = 0.001). During the subsequent 5 month-detraining period, these results were attenuated, but not completely lost when compared to baseline scores [39]. As for neurological functions, the brain-derived neurotrophic factor had a significant enhancement in both active and inactive obese women, as well as the executive function performances following a specific INT training regimen [36]. Last but not least, a specific neuromuscular training program presented significant changes overtime in exercise enjoyment (p = 0.002) compared to a common exercise protocol [44].

Body composition and anthropometry outcomes

With respect to body composition indicators INT appeared to induce similar changes compared to traditional training. Three evidences reported a remarkable reduction in visceral fat (−15.1%, p = 0.004), percent body fat (−7.2, p = 0.001), intermuscular adipose tissue (−23.6, p = 0.001), subcutaneous tight fat (−12.3%, p = 0.002), body weight (−5.5%, p = 0.002) and BMI (−5.2%, p = 0.002) after 12 month of INT [49]. On the same line of evidence, Batrakoulis and colleagues highlighted significant improvements by 1.9% in bone mineral density and 1.5% in bone mineral content [40] with positive changes also in BMI, lean mass and waist circumference [37]. Notably, these ameliorations were mitigated following a 5-month detraining observing a slight weight regain and body composition profile (body mass, p = 0.003; BMI, p = 0.004; waist circumference, p = 0.001; hip circumference, p = 0.015; resting metabolic rate, p = 0.001) without reaching baseline levels [37]. By contrast, non-significant interactions and between-group differences were observed in BMI [41,42,43,44,45], fat mass percentage [41,42,43,44,45], lean mass [43, 45], waist circumference [41,42,43, 49], body weight [44], muscle density [49] and hip circumference [41] suggesting similar changes regardless of the exercise nature (e.g., INT or traditional exercise resistance training).

In summary, these studies analyzed the contribution of the INT regimen on physical fitness and body composition to counteract obesity. In fact, it is well documented that a multidimensional exercise program targeted on the mixture of various fitness components are able to achieve whole-body postural improvements, muscular strength and cardiorespiratory fitness thanks to a more efficient neural plasticity underlying a more proficient motor skill learning [52] and movement competency [26]. An exercise intervention that incorporates INT principles (i.e., health and skill-related variables) focused on dynamic mobility, stability, fundamental movement pattern correction, cardiovascular and cognitive stimuli, may help to develop neural adaptations, new motor units recruitment, intermuscular coordination and strength gains [53, 54]. These findings suggest that the improvements due to INT contribute to better quality of movement and postural control during daily-life activities. This is significant, as increased body weight in known to lead to balance deficits compared to normal-weight individuals [55]. Moreover, an INT regimen characterized by high-intensity body-weight circuit training exercises displayed significant ameliorations in skeletal muscle oxidative capacity, a delay muscle fatigue perception and a cardiovascular endurance improvements [56].

Despite INT exhibits similar results compared to a common intervention in some outcomes (e.g., body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness), INT seems to provide other beneficial implications for obesity as a major daily energy expenditure, and lean mass percentage, bone mineral density, and psychological wellbeing (e.g., enjoyment, vitality, distress regulation and executive function). Nevertheless, body weight, fat mass percentage, waist circumference and BMI tended to have a similar behavior as the other traditional training protocols. From a speculative view point, these body composition findings suggest the key role that a supervised nutritional management may have, in combination with a regular physical activity (preferably based on neuromuscular stimuli) to obtain a more pronounced fat loss and weight reduction [57,58,59].

It is interesting to note that training interruption is a recognized problem that occurs during weight loss interventions, with a frequent tendency to regain body mass reaching values similar to pre-intervention [60]. Noteworthy, an INT protocol appeared to be adequate to mitigate the negative effects of training cessation (i.e., five months) showing slower decrements in both health-related (i.e., cardiovascular, strength, flexibility) and skill-related (e.g., balance, motor coordination) outcomes [37, 38, 40]. Moreover, as INT was shown to improve enjoyment with respect to a traditional training program [44], an INT protocol may be suitable to prevent training interruption.

Lastly, it is worth noting that regular physical exercise that incorporates INT principles is a safe and injury-free option for both children and adults. This is likely due to the multicomponent, high-intensity and intermittent nature of this training, which includes neuromuscular and cognitive tasks enhancing muscular performance and motor coordination, thereby reducing the risk of injury [38].

From a practical perspective, this narrative review lays the initial foundation to promote the usefulness of INT to treat obesity in a population with different age (e.g., younger and older) and anthropometry. These evidence on INT allows fitness coaches, therapists and practitioners to consider INT principles a feasible alternative to the most common exercise intervention used within obesity. Taking this into account, a customized exercise training and a structured nutritional approach may display an important role in supporting individuals with various health conditions, including physical disabilities [61], obesity [62], cancer [63] and diabetes mellitus [64].

Nevertheless, some limitations of the present study should be recognized. First, the narrative nature of the review (as compared to systematic approach with meta-analysis) prevents us to depict firm conclusions about the efficacy of prescribing INT protocols for individuals with obesity. Second, the limited number of electronic databases considered during the searching process may have contributed to limit the discussion of the results. Third, studies utilizing telemedicine approaches were not considered in the present study, although this modality seems to be a new frontier gaining even more attention into research and clinical setting in obesity management [65].

In conclusion, this review highlights the beneficial role of INT programs in improving physical fitness in both younger and older individuals with obesity, with significant ameliorations over short, medium and long time period. The most INT outcomes used in the analyzed studies were cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength, balance, postural control and body composition, with significant remarkable improvements following a specific training intervention based on INT approach targeting both health-related and skill-related physical fitness components. However, BMI, fat mass percentage and waist circumference showed comparable improvements with respects to traditional training exercises. Taken together, these findings support the effectiveness of INT protocols in ameliorating health-related and skill- related physical fitness components. Therefore, fitness coaches and therapists may consider INT as feasible option when working with outpatients with obesity.

References

The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Separate and combined associations of body-mass index and abdominal adiposity with cardiovascular disease: collaborative analysis of 58 prospective studies. Lancet. 2011;377:1085–95.

Ying-Xiu Z, Shu-Rong W. Secular trends in body mass index and the prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents in Shandong, China, from 1985 to 2010. J Public Health. 2012;34:131–7.

Bray GA, Frühbeck G, Ryan DH, Wilding JPH. Management of obesity. Lancet. 2016;387:1947–56.

Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102–138.

Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, Manore MM, Rankin JW, Smith BK, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:459–71.

Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:1451–62.

Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1334–59.

Bushman B. Neuromotor exercise training. ACSMs Health Fit J. 2012;16:4–7.

Wahid A, Manek N, Nichols M, Kelly P, Foster C, Webster P, et al. Quantifying the association between physical activity and cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a systematic - review and meta analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002495.

Ismail I, Keating SE, Baker MK, Johnson NA. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of aerobic vs. resistance exercise training on visceral fat. Obes Rev. 2012;13:68–91.

Oppert JM, Bellicha A, van Baak MA, Battista F, Beaulieu K, Blundell JE, et al. Exercise training in the management of overweight and obesity in adults: Synthesis of the evidence and recommendations from the European Association for the Study of Obesity Physical Activity Working Group. Obes Rev. 2021;22:e13273.

Alizadeh Pahlavani H. Exercise therapy for people with sarcopenic obesity: myokines and adipokines as effective actors. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:811751.

Bouamra M, Zouhal H, Ratel S, Makhlouf I, Bezrati I, Chtara M, et al. Concurrent training promotes greater gains on body composition and components of physical fitness than single-mode training (endurance or resistance) in youth with obesity. Front Physiol. 2022;13:869063.

Schumann M, Feuerbacher JF, Sünkeler M, Freitag N, Rønnestad BR, Doma K, et al. Compatibility of concurrent aerobic and strength training for skeletal muscle size and function: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2022;52:601–12.

Lopez P, Taaffe DR, Galvão DA, Newton RU, Nonemacher ER, Wendt VM, et al. Resistance training effectiveness on body composition and body weight outcomes in individuals with overweight and obesity across the lifespan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2022;23:e13428.

Park W, Ramachandran J, Weisman P, Jung ES. Obesity effect on male active joint range of motion. Ergonomics. 2010;53:102–8.

Jeong Y, Heo S, Lee G, Park W. Pre-obesity and obesity impacts on passive joint range of motion. Ergonomics. 2018;61:1223–31.

Capodaglio P, Cimolin V, Tacchini E, Parisio C, Galli M. Balance control and balance recovery in obesity. Curr Obes Rep. 2012;1:166–73.

Frames CW, Soangra R, Lockhart TE, Lach J, Ha DS, Roberto KA, et al. Dynamical properties of postural control in obese community-dwelling older adults. Sensors. 2018;18;1692.

Faigenbaum AD, Farrell A, Fabiano M, Radler T, Naclerio F, Ratamess NA, et al. Effects of integrative neuromuscular training on fitness performance in children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2011;23:573–84.

Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Ford KR, Best TM, Bergeron MF, Hewett TE. When to initiate integrative neuromuscular training to reduce sports-related injuries and enhance health in youth? Curr Sports Med Rep. 2011;10:155–66.

Tompsett C, Burkett B, McKean MR. Comparing performances of fundamental movement skills and basic human movements: a pilot study. J Fitness Res. 2015;4:13–25.

Fort-Vanmeerhaeghe A, Romero-Rodriguez D, Montalvo AM, Kiefer AW, Lloyd RS, Myer GD. Integrative neuromuscular training and injury prevention in youth athletes. Part I: identifying risk factors. Strength Cond J. 2016;38:36–48.

Akbar S, Soh KG, Jazaily Mohd Nasiruddin N, Bashir M, Cao S, Soh KL. Effects of neuromuscular training on athletes physical fitness in sports: a systematic review. Front Physiol. 2022;13:939042.

Faigenbaum AD, Myer GD, Farrell A, Radler T, Fabiano M, Kang J, et al. Integrative neuromuscular training and sex-specific fitness performance in 7-year-old children: an exploratory investigation. J Athl Train. 2014;49:145–53.

Trecroci A, Invernizzi PL, Monacis D, Colella D. Actual and perceived motor competence in relation to body mass index in primary school-aged children: a systematic review. Sustainability. 2021;13:9994.

Lloyd RS, Faigenbaum AD, Stone MH, Oliver JL, Jeffreys I, Moody JA, et al. Position statement on youth resistance training: the 2014 International Consensus. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:498–505.

Trecroci A, Rossi A, Dos’Santos T, Formenti D, Cavaggioni L, Longo S, et al. Change of direction asymmetry across different age categories in youth soccer. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9486.

Sañudo B, Sánchez-Hernández J, Bernardo-Filho M, Abdi E, Taiar R, Núñez J. Integrative neuromuscular training in young athletes, injury prevention, and performance optimization: a systematic review. Appl Sci. 2019;9:3839.

Guzmán-Muñoz E, Sazo-Rodriguez S, Concha-Cisternas Y, Valdés-Badilla P, Lira-Cea C, Silva-Moya G, et al. Four weeks of neuromuscular training improve static and dynamic postural control in overweight and obese children: a randomized controlled trial. J Mot Behav. 2020;52:761–9.

Molina-Garcia P, Miranda-Aparicio D, Molina-Molina A, Plaza-Florido A, Migueles JH, Mora-Gonzalez J, et al. Effects of exercise on plantar pressure during walking in children with overweight/obesity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020;52:654–62.

Molina-Garcia P, Molina-Molina A, Smeets A, Migueles JH, Ortega FB, Vanrenterghem J. Effects of integrative neuromuscular training on the gait biomechanics of children with overweight and obesity. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2022;32:1119–30.

Molina-Garcia P, Mora-Gonzalez J, Migueles JH, Rodriguez-Ayllon M, Esteban-Cornejo I, Cadenas-Sanchez C, et al. Effects of exercise on body posture, functional movement, and physical fitness in children with overweight/obesity. J Strength Cond Res. 2020;34:2146–55.

Bonney E, Ferguson G, Burgess T, Smits-Engelsman B. Benefits of activity-based interventions among female adolescents who are overweight and obese. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2019;31:338–45.

Fort-Vanmeerhaeghe A, Romero-Rodriguez D, Lloyd RS, Kushner A, Myer GD. Integrative neuromuscular training in youth athletes. Part II: strategies to prevent injuries and improve performance. Strength Cond J. 2016;38:9–27.

Alizadeh M, Dehghanizade J. The effect of functional training on level of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and functional performance in women with obesity. Physiol Behav. 2022;251:113798.

Batrakoulis A, Jamurtas AZ, Georgakouli K, Draganidis D, Deli CK, Papanikolaou K, et al. High intensity, circuit-type integrated neuromuscular training alters energy balance and reduces body mass and fat in obese women: a 10-month training-detraining randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0202390.

Batrakoulis A, Jamurtas AZ, Tsimeas P, Poulios A, Perivoliotis K, Syrou N, et al. Hybrid-type, multicomponent interval training upregulates musculoskeletal fitness of adults with overweight and obesity in a volume-dependent manner: a 1-year dose-response randomised controlled trial. Eur J Sport Sci. 2022;1–12.

Batrakoulis A, Loules G, Georgakouli K, Tsimeas P, Draganidis D, Chatzinikolaou A, et al. High-intensity interval neuromuscular training promotes exercise behavioral regulation, adherence and weight loss in inactive obese women. Eur J Sport Sci. 2020;20:783–92.

Batrakoulis A, Tsimeas P, Deli CK, Vlachopoulos D, Ubago-Guisado E, Poulios A, et al. Hybrid neuromuscular training promotes musculoskeletal adaptations in inactive overweight and obese women: a training-detraining randomized controlled trial. J Sports Sci. 2021;39:503–12.

Bezzoli E, Andreotti D, Pianta L, Mascheroni M, Piccinno L, Puricelli L, et al. Motor control exercises of the lumbar-pelvic region improve respiratory function in obese men. A pilot study. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40:152–8.

Cavaggioni L, Gilardini L, Redaelli G, Croci M, Capodaglio P, Gobbi M, et al. Effects of a randomized home-based quality of movement protocol on function, posture and strength in outpatients with obesity. Healthcare. 2021;9:1451.

Feito Y, Patel P, Sal Redondo A, Heinrich KM. Effects of eight weeks of high intensity functional training on glucose control and body composition among overweight and obese adults. Sports. 2019;7:51.

Heinrich KM, Patel PM, O’Neal JL, Heinrich BS. High-intensity compared to moderate-intensity training for exercise initiation, enjoyment, adherence, and intentions: an intervention study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:789.

La Scala Teixeira CV, Caranti DA, Oyama LM, Padovani RdaC, Cuesta MGS, Moraes ADS, et al. Effects of functional training and 2 interdisciplinary interventions on maximal oxygen uptake and weight loss of women with obesity: a randomized clinical trial. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2020;45:777–83.

Maffiuletti NA, Agosti F, Proietti M, Riva D, Resnik M, Lafortuna CL, et al. Postural instability of extremely obese individuals improves after a body weight reduction program entailing specific balance training. J Endocrinol Invest. 2005;28:2–7.

Rojhani-Shirazi Z, Azadeh Mansoriyan S, Hosseini SV. The effect of balance training on clinical balance performance in obese patients aged 20–50 years old undergoing sleeve gastrectomy. EurSurg. 2016;48:105–9.

Cambiriba, Santos AR, Marques IC, de DC, Oliveira S, de FM, et al. Effects of two resistance exercise programs on the health-related fitness of obese women with pain symptoms in the knees. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina Humana. 2021;22:30–41.

Santanasto AJ, Newman AB, Strotmeyer ES, Boudreau RM, Goodpaster BH, Glynn NW. Effects of changes in regional body composition on physical function in older adults: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19:913–21.

Myers TR, Schneider MG, Schmale MS, Hazell TJ. Whole-body aerobic resistance training circuit improves aerobic fitness and muscle strength in sedentary young females. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29:1592.

McRae G, Payne A, Zelt JGE, Scribbans TD, Jung ME, Little JP, et al. Extremely low volume, whole-body aerobic-resistance training improves aerobic fitness and muscular endurance in females. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37:1124–31.

Kleim JA, Jones TA. Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008;51:S225–39.

Grosset JF, Piscione J, Lambertz D, Pérot C. Paired changes in electromechanical delay and musculo-tendinous stiffness after endurance or plyometric training. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;105:131–9.

Folland JP, Williams AG. The adaptations to strength training: morphological and neurological contributions to increased strength. Sports Med. 2007;37:145–68.

Mignardot JB, Olivier I, Promayon E, Nougier V. Origins of balance disorders during a daily living movement in obese: can biomechanical factors explain everything? PLoS One. 2013;8:e60491.

Ouerghi N, Fradj MKB, Bezrati I, Khammassi M, Feki M, Kaabachi N, et al. Effects of high-intensity interval training on body composition, aerobic and anaerobic performance and plasma lipids in overweight/obese and normal-weight young men. Biol Sport. 2017;34:385–92.

Bellicha A, van Baak MA, Battista F, Beaulieu K, Blundell JE, Busetto L, et al. Effect of exercise training on weight loss, body composition changes, and weight maintenance in adults with overweight or obesity: an overview of 12 systematic reviews and 149 studies. Obes Rev. 2021;22:e13256.

Wadden TA, West DS, Neiberg RH, Wing RR, Ryan DH, Johnson KC, et al. One-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: factors associated with success. Obesity. 2009;17:713–22.

Jakicic JM, Marcus BH, Lang W, Janney C. Effect of exercise on 24-month weight loss maintenance in overweight women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1550–9.

Miller BML, Brennan L. Measuring and reporting attrition from obesity treatment programs: a call to action! Obes Res Clin Pract. 2015;9:187–202.

Cavaggioni L, Trecroci A, Tosin M, Iaia FM, Alberti G. Individualized dry-land intervention program for an elite Paralympic swimmer. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2019;59:82–6.

Dvorák M, Tóth M, Ács P. The role of individualized exercise prescription in obesity management-case study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:12028.

Klika RJ, Callahan KE, Drum SN. Individualized 12-week exercise training programs enhance aerobic capacity of cancer survivors. Phys Sportsmed. 2009;37:68–77.

Doupis J, Karras K, Avramidis K. The role of individualized exercise prescription in type 2 diabetes mellitus management. TouchREV Endocrinol. 2021;17:2–4.

Gilardini L, Cancello R, Cavaggioni L, Bruno A, Novelli M, Mambrini SP, et al. Are people with obesity attracted to multidisciplinary telemedicine approach for weight management? Nutrients. 2022;14:1579.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano (approval number 2022_09_27_15).

Funding

This work was supported by Italian Ministry of Health - Ricerca Corrente.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LC: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing and draft preparation; LG: writing, review and editing; MC: visualization and supervision; DF: formal analysis, writing and original draft preparation; GM: visualization and supervision; SB: Conceptualization, methodology and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cavaggioni, L., Gilardini, L., Croci, M. et al. The usefulness of Integrative Neuromuscular Training to counteract obesity: a narrative review. Int J Obes 48, 22–32 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-023-01392-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-023-01392-4