Abstract

The hypothesis that postnatal nicotine exposure weakens cardiorespiratory recovery from reflex apnea and bradycardia was tested in eight lambs continuously infused with nicotine from the day of birth at a dose of 1 to 2 mg·kg−1·d−1. Eight age-matched lambs infused with saline served as controls. Apnea and bradycardia were elicited by laryngeal stimulation with 1 mL of water (laryngeal chemoreflex) both during air breathing [0.21 fraction of inspired oxygen (Fio2)] and mild hypoxia (0.10 Fio2) at a mean postnatal age of 5 ± 1, 14 ± 1, and 28 ± 1 d. Ventilation, heart rate, and blood pressure were similar in the two groups at rest. In response to laryngeal chemoreflex stimulation, nicotine-treated lambs had a more pronounced decrease in ventilation (p < 0.05), longer reflex apnea (p < 0.001 in 0.21 Fio2;p < 0.01 in 0.10 Fio2), and greater reflex bradycardia (p < 0.01). During reflex apnea, sighs were less efficient in restoring heart rate to prestimulation level, and a greater decrease in heart rate was observed before sighs in nicotine-treated lambs. These effects were most apparent at 5 d of age, when nicotine-treated lambs also had lower ventilation during hypoxia (p < 0.05). The response to hyperoxia was comparable in the two groups at all ages. The ability to terminate laryngeal chemoreflex-induced apnea is attenuated in young lambs continuously exposed to nicotine. This attenuation is present both in normoxia and in hypoxia and is accompanied by reduced effects from sighing on cardiac autoresuscitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Laryngeal stimulation with fluids potentially harmful to the airways induces a graded and reproducible reflex response consisting of laryngeal constriction, swallowing, and apnea followed by hypoventilation (1). The inhibition of respiration is accompanied by a cardiovascular response consisting of bradycardia, peripheral vasoconstriction, and redistribution of blood flow (2, 3). This response may be particularly strong in young mammals and lead to cardiovascular collapse and death (4). Termination of LCR apnea relies on mechanisms similar to those that modulate the cardiorespiratory response to hypoxia, i.e. sympathetic activation, increased alertness, and augmented peripheral chemoreceptor and baroreceptor sensory discharge. The clinical importance of these escape and defense mechanisms are supported by observations that infants who are at risk for life-threatening events are also less able to recover from LCR-induced reflex apnea and bradycardia (5, 6)

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that long-term postnatal exposure to nicotine attenuates and prolongs recovery from apnea and bradycardia in response to LCR stimulation. This notion was based on our previous observations that postnatal nicotine exposure leads to an attenuation of cardiorespiratory defense mechanisms to hypoxia (7). We therefore assumed that nicotine, which has effects on both sympathetic regulation and the ventilatory response to hypoxia, could adversely affect cardiorespiratory recovery from induced apnea.

Inasmuch as attenuation of chemoreceptor oxygen sensitivity is a known mechanism of prolonged cardiorespiratory recovery after LCR stimulation (8), we also determined whether an altered LCR response in nicotine-treated lambs was associated with changes in CB oxygen sensitivity, as tested by the magnitude of ventilatory response to hypoxia and hyperoxia.

The subjects were studied on three study occasions, which were chosen to approximately reflect human development from 1 to 12 mo of age. We used chronically instrumented, unanesthetized lambs, an animal model used in our laboratory in a number of studies addressing the mechanisms of hypoxic defense, LCR response, and effects of nicotine (7–9).

METHODS

Subjects

Eight lambs of mixed breed forming the N group were continuously infused s.c. for 4 wk with nicotine tartrate starting on the day of birth using osmotic pumps (Alzet model 2ML4; Alza Corp., Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.). The infusion started at 2 mg·kg−1·d−1, and when the lambs had gained weight so that the infusion rate had decreased to approximately 1 mg·kg−1·d−1, new pumps delivering 2 mg·kg−1·d−1 were implanted. Eight lambs were used as a C group and were infused by Alzet pumps containing normal saline.

The lambs were studied at an age of 5 ± 1, 14 ± 1, and 28 ± 1d (mean ± SEM). Body weights of the lambs at the time of the studies were 5.6 ± 0.7, 7.8 ± 0.9, and 12.0 ± 1.3 kg for the C group and 5.8 ± 0.4, 8.3 ± 0.5, and 12.3 ± 1.1 kg for the N group, respectively. When not studied, the lambs were reared with their mothers and nursed ad libitum. Both the N and the C lambs were clinically well and gained weight at a similar pace.

Instrumentation

The lambs were instrumented with placement of a tracheal window and arterial and venous catheters at the age of 1–3 d (7, 8). When not studied, tracheal patency was reestablished with a piece of endotracheal tube (Portex, Keene, NH, U.S.A.). At least 48 h of postoperative recovery was allowed before the first study. Gentamicin 4 mg/kg and carbenicillin 100 mg/kg were given daily. At the time of each study, the tracheostomy prosthesis was removed, and through the tracheostoma a biluminal balloon catheter (8F Foley) was inserted and directed upward with the tip placed in the larynx. A tight-fitting cuffed endotracheal tube was directed downward. The Vanderbilt University Animal Care Committee approved the research protocol.

Study Equipment

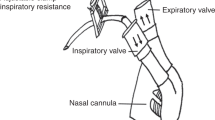

The technique used for breath-by-breath measurement of inspiratory volumes has previously been described elsewhere (7, 10, 11). Briefly, lambs were breathing spontaneously through the endotracheal tube, which was connected to the horizontal leg of a T-shaped valve assembly. The inspiratory side consisted of a pneumotachometer (model 21071B, size 1; Hewlett Packard, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.) and a pneumatic occlusion valve also acting as a one-way inspiratory valve. The expiratory side consisted of a low-resistance expiratory valve and a flap valve, acting as a variable expiratory resistance similar to laryngeal expiratory braking activity. The flow-resistive characteristics of this valve produced a pressure peak at the beginning of expiration of 2.5–3 cm H2O followed by a gradual pressure decline to a lowest pressure of 0.5 cm H2O at end-expiration. The valve assembly permitted breath-by-breath measurements of inspiratory flows and volumes with minimal or no effects on ventilation and breathing pattern (11). The lambs were monitored during the experimental period with continuous recordings of mean arterial BP (model P23 ID; Gould-Statham, Oxnard, CA, U.S.A.), HR (H-P model 211376A rate computer), and serial blood gas analyses (Corning, model 158, PH/Blood Gas Analyzer; Ciba Corning Diagnostics Corp., Medfield, MA, U.S.A.). The analog signals of inspiratory airflow, HR, and BP were sampled in real time, converted to digital form at 200 Hz in a 12-bit analog-to-digital converter card, and stored on the disk of an IBM-compatible personal computer. VI was computed from the inspiratory flow on a breath-by-breath basis (11).

Test Protocol

The lambs were studied unanesthetized, slightly restrained in a sling (Alice King Chatham, Medical Arts, Los Angeles, CA, U.S.A.) while they were awake and relaxed (open eyes, regular breathing, and absence of body movements). The test sequence consisted of measurement of resting ventilation followed by two LCR stimulations, two hyperoxia tests, a hypoxia test, and two LCR stimulations during hypoxia. There was at least 5 min between hyperoxia tests, 15 min between hyperoxia and hypoxia tests, and 3 min between LCR tests.

Measurement of Resting VI, HR, and BP during Normoxia

At the beginning of each study day, we sampled a representative 5-min recording of quiet breathing (approximately 200 breaths) during baseline room air conditions. This 5-min control period was used to ensure that the baseline recordings of VI, HR, and BP obtained before each test were representative. For analysis of the LCR response, a 30-s baseline obtained immediately before the stimulation was used as a control period.

Ventilatory Response to Hyperoxia

During resting ventilation, the inspired gas was abruptly switched from ambient air to 100% O2. An interval of 20 s before the switch was used as a baseline period, and the first 10 s (or first five breaths, whichever came first) after the switch was used as the test period. If the 10-s period ended between two breaths, the complete next breath was included in the analysis. The decrease in minute ventilation (expressed as percent of baseline) was used as an index of chemoreceptor response. Two tests, 5 min apart, were performed at each age.

Ventilatory Response to Hypoxia

During resting ventilation, inspired gas was abruptly switched from ambient air to 10% O2 in nitrogen. The last minute before the switch was used as a baseline period. The hypoxic challenge was maintained for 10 min. Isocapnia was not maintained. An arterial blood sample for determination of Po2 and Pco2 was obtained during each minute of hypoxia.

Laryngeal Water Stimulation

Each trial consisted of a 30-s baseline period of regular breathing followed by a retrograde injection of 1 mL of sterile water at room temperature through the Foley catheter during a 5-s period. Respiration, BP, and HR were continuously monitored to indicate that the lambs had returned to the original baseline state before the next test was performed. Two water stimulations were performed in air and in hypoxia. Stimulations during acute hypoxemia began 10 min after the switch to hypoxia.

Interpretation of Response and Data Analysis

The effects of LCR stimulation were assessed by the following means:

-

1

As percent change in VI during the 30-s period after onset of stimulation compared with the 30-s baseline immediately preceding stimulation.

-

2

As duration of continuous apnea measured in seconds.

-

3

As recovery time defined as the time from onset of stimulation until respiration became regular for at least 10 consecutive seconds.

-

4

As the number of sighs occurring after LCR stimulation, and the number of gasps or sighs needed to restore HR and regular breathing. A breath was defined as a sigh if it showed a ramplike inspiratory profile and the tidal volume was at least twice that of the preceding breath. A breath of similar size with a spikelike inspiratory profile was defined as a gasp. Because only sighs could be positively identified in this study, this term will be used during the remainder of this paper.

-

5

As percent decrease in HR, which was determined from the BP tracing during a 4-s window at baseline and when the lowest value after the onset of the stimulus was attained.

-

6

As percent increase in mean BP from baseline. The maximum increase in mean BP during a 4-s window after the stimulation was used.

Tests were accepted as valid if the pretest baseline was stable, free of visible oscillations, and not interrupted by sighs or cough.

Nicotine and Cotinine Concentrations

Plasma concentrations of nicotine and cotinine were determined by an HPLC method (12).

Statistical Methods

LCR response.

Tests were performed with paired t test to determine whether LCR stimulation had a significant effect on VI, HR, and BP within each age group (5, 14, and 28 d), within each environment (0.21 Fio2 and 0.1 Fio2), and within each treatment group (C and N). The overall effects of nicotine on LCR response with regard to the age at test and environment (0.21 Fio2 and 0.1 Fio2) were evaluated by MR or three-factor RM-ANOVA (two within factors: time and Fio2; one between factor: drug). For all tests performed, the two observations on each animal on each study occasion were averaged to a single measurement. If a significant result was found in the MR, we performed individual comparisons between or within groups with paired t test. Given the large number of statistical tests performed, we are only reporting consistent overall patterns, although some variables may have been significantly different in individual comparisons. Simple regression was used to determine whether there was a correlation between nicotine and cotinine plasma concentrations and apnea duration and changes in nicotine and cotinine concentrations over time.

Resting ventilation, hypoxia, and hyperoxia.

Two-factor RM-ANOVA (two within factors: time and drug) was used to compare VI, HR, BP, Po2, and Pco2 between the two groups on the three study occasions. The initial response to hypoxia (first 4 min of test) was analyzed by regression analysis as the rate of increase in ventilation in response to decreasing Po2. Two-factor RM-ANOVA (time and drug) was used to compare the minute ventilation between the groups during the test. Significant overall effects were compared by t test between individual groups. Results are presented as mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

Baseline values before laryngeal stimulation.

Ventilation, Po2, and Pco2 were similar in the two study groups on all three study occasions (Table 1A). Resting HR in 0.21 Fio2 was similar in the two groups but lower in the N lambs in 0.1 Fio2 (RM-ANOVA, p < 0.05). No differences between the groups were noted in BP.

Ventilatory changes after LCR stimulation.

Laryngeal stimulation induced a greater inhibition of ventilation in the N lambs both in 0.21 Fio2 and in 0.1 Fio2 (RM-ANOVA, p < 0.05), which was particularly noticeable at age 5 d but also present at 14 d (p < 0.07;Fig. 1, A and B). Ventilatory inhibition was greater in 0.21 Fio2 compared with 0.1 Fio2 in both the N and the C lambs (RM-ANOVA, p < 0.05). The ventilatory inhibition decreased with increasing postnatal age in the N lambs (MR, p < 0.05), but no such correlation was seen in the C group.

Ventilatory response (percent change in ventilation volume during 30 s) to laryngeal water stimulation in eight C and eight N lambs during tests performed in 0.21 Fio2 (A) and in 0.1 Fio2 (B). Duration of apnea resulting from laryngeal water stimulation performed in 0.21 Fio2 (C) and in 0.1 Fio2 (D). Values are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 for difference in response compared with C; **p < 0.01 for difference in response compared with C; +p < 0.05 for difference in response compared with 0.21 Fio2; ++p < 0.01 for difference in response compared with 0.21 Fio2.

Apnea, recovery time, and sighing.

Poststimulation apnea was longer in the N lambs compared with the C lambs both in 0.21 Fio2 and 0.1 Fio2 (RM-ANOVA, p < 0.001 for 0.21 Fio2 and p < 0.01 for 0.1 Fio2;Fig. 1, C and D). In individual age groups, apnea duration was significantly longer in the N lambs at 5 d (p < 0.01), 14 d (p < 0.05), and 28 d (p < 0.05) in 0.21 Fio2 and at 5 d in 0.1 Fio2 (p < 0.01).

The longer poststimulation apnea in the N lambs was accompanied by a prolongation of the recovery time in both 0.21 Fio2 and 0.1 Fio2 (MR, p < 0.05;Table 1B). N lambs took significantly more sighs than the C lambs during the recovery period in both 0.21 Fio2 and 0.1 Fio2 (RM-ANOVA, p < 0.001;Table 1B). The 5-d-old N lambs started to sigh after a much greater decrease in HR compared with C lambs (Fig. 2, A and B). Sighs increased HR to a much lesser extent in the N than in the C lambs, and bradycardia persisted even at the onset of regular breathing. An example of sighs in an N lamb that only produced transient effects on HR and did not lead to resumption of regular breathing is presented in Figure 3A. By contrast, one sigh usually restored prestimulation HR and regular breathing in C lambs (Fig. 3B).

HR response (percent change from baseline) to laryngeal water stimulation before and after sighs and at the onset of regular breathing in eight C and eight N lambs during tests performed in 0.21 Fio2 (A) and in 0.1 Fio2 (B). HR response expressed as maximal percent change from baseline during tests performed in 0.21 Fio2 (C) and in 0.1 Fio2 (D). Values are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 for difference in response compared with C; ***p < 0.001 for difference in response compared with C.

Response to LCR stimulation (LCS) in a 6-d-old N lamb performed in 0.21 Fio2 showing BP, HR, and VI (A). Note the reflex-induced apnea, marked bradycardia, and hypertension. The first sigh at 1 did not lead to resumption of regular breathing and only produced a transient effect on HR, which returned to the lowest level at 2. The sigh at 3 improved HR slightly. Sighs at 4 and 5 improved HR and induced irregular breathing. At 6, 70 s after onset of laryngeal stimulation, regular breathing has resumed, but HR is still well below baseline. Response to LCS in a 4 - d-old C lamb performed in 0.21 Fio2 induced a less severe response (B). Note that one sigh at 1 is followed by resumption of regular breathing and increased HR to approximately baseline level at 2.

Cardiovascular response to laryngeal stimulation.

Poststimulation bradycardia (lowest attained HR) was more profound in the N lambs compared with the C lambs in both 0.21 Fio2 and 0.1 Fio2 (RM-ANOVA, p < 0.01) at 5 and 14 d (Fig. 2, C and D). The degree of poststimulation bradycardia was similar in tests performed in 0.21 Fio2 and 0.1 Fio2.

N lambs also had a significantly greater increase in BP in both 0.21 Fio2 and 0.1 Fio2 compared with the C lambs (Fig. 4, A and B). There was an overall effect of nicotine (RM-ANOVA, p < 0.01) and an overall effect of hypoxia (p < 0.05), insofar that the BP elevation was greater in 0.1 Fio2 compared with 0.21 Fio2, particularly noticeable at an age of 14 and 28 d. When individual age groups were analyzed, the BP response was significantly higher in the N group than in the C group in both 0.21 Fio2 and 0.1 Fio2 (RM-ANOVA, p < 0.05) at 5 d of age.

Mean arterial BP response (maximal percent change from baseline) to laryngeal water stimulation performed in eight C and eight N lambs during tests in 0.21 Fio2 (A) and in 0.1 Fio2 (B). Ventilatory response to acute hypoxia (0.1 Fi O2) was performed at 5 d (C), 14 d (D), and at 28 d (E). Values are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 for difference in response compared with C; ++p < 0.01 for difference in response compared with 0.21 Fio2.

Ventilatory response to hyperoxia.

Hyperoxia induced a similar decrease in ventilation in N and C lambs at all age groups: 33.9 ± 13% and 36.8 ± 12.7% at 5 d, 50.9 ± 19.7% and 40.8 ± 13.7% at 14 d, and 54.7 ± 13.6% and 48.8 ± 20.4% at 28 d, respectively. There was an overall increase in the response to hyperoxia with age in the N (p < 0.05) but not in the C lambs.

Ventilatory response to hypoxia.

The 5-d-old N lambs had significantly lower ventilation volumes throughout the entire 10-min test (paired t test, p < 0.001l Fig. 4C). The response calculated as the rate of increase in ventilation in response to decreasing Po2 was somewhat lower at 5 d of age in N lambs (4.5 ± 0.5 versus 5.5 ± 2.1 mL/mm Hg Po2 in C lambs;p < 0.05). The response was similar in N and C lambs at 14 and 28 d (Fig. 4, D and E).

Nicotine and cotinine plasma concentrations.

There were no significant differences in nicotine and cotinine concentrations among the three age groups. Nicotine levels were 29.4 ± 8.6, 26.6 ± 7.4, and 12.1 ± 1.9 ng/mL at 5, 14, and 28 d, respectively (p < 0.19), and cotinine levels were 131.6 ± 23.2, 99.2 ± 15.7, and 73.1 ± 10.6 ng/mL at 5, 14, and 28 d, respectively (p < 0.08). The variations among individual lambs could, in part, explain the lack of significance. However, the changes in nicotine and cotinine levels in individual lambs showed a decrease with age (r = −2.7, p < 0.01 for cotinine and r = −0.77, p < 0.05 for nicotine). Plasma cotinine or nicotine plasma concentrations tended to follow the magnitude of LCR-induced ventilatory inhibition at a significance level of p = 0.06, but not the duration of LCR-induced apnea.

DISCUSSION

We found that laryngeal stimulation produces profound cardiorespiratory depression and delayed recovery in young lambs continuously exposed to nicotine after birth. A contributing factor appeared to be less-efficient cardiorespiratory recovery by sighing in N lambs. This was frequently observed in the 5-d-old N animals in which sighs did not lead to rapid restoration of HR and regular breathing. After LCR stimulation in hypoxia, some of these animals developed a shocklike state with sudden loss of muscle tone and unresponsiveness to external stimuli, i.e., symptoms associated with cardiorespiratory collapse and risk of death.

Our findings that postnatal nicotine exposure interferes with the mechanisms of cardiorespiratory recovery that terminate reflex apnea and bradycardia correlated with young age but not with individual plasma concentrations of nicotine or cotinine. However, a dose-response effect may not have been possible to evaluate, both because of the limited number of animals studied and because most treated animals had relatively high nicotine plasma concentrations, comparable to those of habitual smokers.

CB Chemoreceptor Activity and LCR Response

Previous work from this laboratory has emphasized that resumption of breathing and increase in HR after LCR-induced apnea are facilitated by an increased CB chemoreceptor activity and an increased sympathetic tone (9). Sladek et al. (8), Grogaard et al. (9), and Grogaard and Sundell (13) could demonstrate that surgical denervation of the CB chemoreceptors resulted in extreme prolongation of LCR-induced apnea, whereas stimulation of CB chemoreceptors by hypoxemia or β-adrenergic agonists shortened LCR-induced apnea and the postapneic respiratory depression. We therefore compared the LCR response in room air with the response during CB chemoreceptor stimulation with mild hypoxia. We expected the LCR response to be augmented during hypoxemia in N lambs, as our initial hypothesis was that LCR-induced apnea would be prolonged and also accompanied by a nicotine-induced attenuation of CB oxygen sensitivity. However, the duration of LCR-induced apnea was not longer during hypoxemia. Although the N lambs had lower ventilatory volumes, we did not observe any convincing difference in the ventilatory response to hypoxia. The ventilatory response to hyperoxia was also similar in both groups. It is, therefore, less likely that the prolonged cardiorespiratory inhibition after LCR stimulation in the N lambs can be attributed to a reduction in CB oxygen sensitivity.

LCR Response and Sympathetic Activity

Slotkin et al. (14, 15) have reported that adrenomedullary catecholamine release, an essential component of sympathetic stress activation, is deficient in prenatally nicotine-treated rat pups. These animals also showed an impaired chronotropic response to hypoxemia and, in addition, a suppressed neuronal activity in the forebrain and brainstem respiratory-related areas.

To what extent these results are applicable to postnatally treated animals, as in this study, is unclear. Chronic postnatal administration is known to desensitize the acetylcholine receptors, resulting in decreased norepinephrine and dopamine release from adrenergic neuron pools that regulate sympathetic tone (16, 17). The desensitization is rapid with regard to mechanisms that mediate the cardiovascular and alerting effects and the ability to increase sympathetic outflow in response to stress (18), particularly in locus ceruleus, an area associated with arousal, alertness, and vigilance (18, 19).

Some of the marked respiratory and cardiovascular depression after LCR stimulation in room air is likely to be related to a lower ability for sympathetic activation. Such a deficit would be particularly apparent during air breathing when stimulation from the CB may not be sufficient to overcome the respiratory inhibition.

Sighing and cardiorespiratory recovery.

It is believed that LCR stimulation suppresses respiration through inhibition of central respiratory neuron pools located around the nucleus of the solitary tract, and this inhibition can be reproduced by stimulation of the superior laryngeal nerve (20). The associated reflex bradycardia is of vagal origin, and its termination is dependent on resumption of breathing movements, or more specifically, by lung inflation (3, 21). Young mammals can easily change their breathing pattern to sighing, which may progress to gasping, both of which are considered essential for survival inasmuch as they efficiently restore regular breathing and raise HR (22, 23). Although sighs and gasps serve the same purpose of promoting cardiorespiratory recovery, gasps occur during severe hypoxemia and can be distinguished from sighs by their burstlike increase in inspiratory effort that do not resemble augmented eupneic breaths. There is neurophysiologic evidence that sighs and gasping are unique breathing patterns different from eupnea and regulated from specific medullary areas (24, 25).

Our observation that N lambs have more frequent sighs than C lambs is not entirely consistent with studies of rat pups in anoxia, in which no difference in the number of gasps was observed (26). N lambs had more sighs, and these efforts appeared less efficient in restoring a sustained rise in HR and regular breathing. Sighing and gasping are considered to be key elements in successful cardiorespiratory recovery (27), and our findings of less-efficient sighs support other reports that nicotine exposure impairs the ability to autoresuscitate in situations such as repeated hypoxic exposures or LCR-induced apnea after IL-1B pretreatment (15, 28, 29).

Although there seems to be an agreement that nicotine given to young mammals may adversely affect survival by decreasing the chances of successful cardiorespiratory recovery, the underlying mechanisms appear less clear. Slotkin et al. (15) have stressed the importance of adrenomedullary catecholamine release during hypoxic stress and demonstrated a deficient mechanism in prenatally exposed rat pups, and other investigators have supported this notion. Whereas the efficiency of gasping appears to be dependent on sympathetic tone, the frequency of gasps and sighs are controlled by specific neural networks and are not affected by, for example, sympathetic blockade (30).

Effects of nicotine on postnatal development.

Augmentation of the LCR response was most apparent in the 5-d-old lambs and decreased gradually with age. Also at the youngest age, the animals had consistently lower ventilatory volumes during the hypoxic challenge, an observation also made by Ueda et al. (31) in human infants. The reduced ability to break LCR-induced apnea and bradycardia in N lambs was most apparent in the youngest lambs as well and also decreased with advancing postnatal age. There may be several alternative explanations as to why the adverse effects of nicotine were less marked in older animals.

A nonneurogenic release of catecholamines during autoresuscitation and gasping plays a more important role as a defense mechanism in the newborn (32), and specific effects of nicotine on this defense strategy would be expected to become less important with increasing age. Although not apparent in the C group in this study, it has previously been shown that the magnitude of cardiorespiratory inhibition in response to LCR stimulation is strongest in the newborn period and decreases thereafter (8, 9, 33). Both these factors would imply that the most marked effects of nicotine are to be seen early. As previously mentioned, no dose-response effects between the physiologic effects and serum concentrations of nicotine or cotinine were seen in the present study. In addition, serum nicotine and cotinine levels tended to be lower in the oldest age group in spite of a similar dosage per body weight. Such a change could imply a higher metabolism and consequently development of pharmacologic tolerance, although the rapid growth of the lambs with increasing postnatal age and individual variations in nicotine metabolism could be an additional factor explaining why we were not able to prevent a decrease over time in plasma nicotine and cotinine levels. We chose a nicotine regimen used in many other developmental studies, 1 to 2 mg/kg per day. This dose is much lower than that used by many other investigators, but it nevertheless produced plasma nicotine levels more comparable to light habitual smokers than to infants of smoking mothers (34, 35). Our previous studies of lambs given low intermittent doses, with plasma levels more reminiscent of exposed infants, would suggest that the dose used in the present study may have been in excess of what is necessary to produce physiologic effects.

CONCLUSION

We have found that the ability to terminate LCR-induced apnea is markedly attenuated in young lambs continuously exposed to nicotine. This attenuation is present both during normoxia and hypoxia and appears to be related to reduced effects from sighing on cardiac autoresuscitation. The implications of these findings on postnatal tobacco exposure in human infants are that a smoke-free environment should be given a high priority.

Abbreviations

- BP:

-

mean arterial blood pressure

- C:

-

control

- CB:

-

carotid body

- Fio2:

-

fraction of inspired oxygen

- HR:

-

heart rate

- LCR:

-

laryngeal chemoreflex

- MR:

-

multivariate regression analysis

- N:

-

nicotine-treated

- Po2:

-

arterial Po2

- Pco2:

-

arterial Cco2

- RM-ANOVA:

-

repeated measures analysis of variance

- VI:

-

inspiratory minute ventilation

References

Kovar I, Selstam U, Catterton WZ, Stahlman MT, Sundell HW 1979 Laryngeal chemoreflex in newborn lambs: respiratory and swallowing response to salts, acids, and sugars. Pediatr Res 13: 1144–1149

Elsner R, Angell-James JE, de Burgh Daly M 1977 Carotid body chemoreceptor reflexes and their interactions in the seal. Am J Physiol 232: H517–H525

Grogaard J, Lindstrom DP, Stahlman MT, Marchal F, Sundell H 1982 The cardiovascular response to laryngeal water administration in young lambs. J Dev Physiol 4: 353–370

Harding R, Johnson P, McClelland ME 1978 Liquid-sensitive laryngeal receptors in the developing sheep, cat and monkey. J Physiol (Lond) 277: 409–422

van der Hal AL, Rodriguez AM, Sargent CW, Platzker AC, Keens TG 1985 Hypoxic and hypercapneic arousal responses and prediction of subsequent apnea in apnea of infancy. Pediatrics 75: 848–854

Wennergren G, Hertzberg T, Milerad J, Bjure J, Lagercrantz H 1989 Hypoxia reinforces laryngeal reflex bradycardia in infants. Acta Paediatr Scand 78: 11–17

Milerad J, Larsson H, Lin J, Sundell HW 1995 Nicotine attenuates the ventilatory response to hypoxia in the developing lamb. Pediatr Res 37: 652–660

Sladek M, Grogaard JB, Parker RA, Sundell HW 1993 Prolonged hypoxemia enhances and acute hypoxemia attenuates laryngeal reflex apnea in young lambs. Pediatr Res 34: 813–820

Grogaard J, Kreuger E, Lindstrom D, Sundell HW 1986 Effects of carotid body maturation and terbutaline on the laryngeal chemoreflex in newborn lambs. Pediatr Res 20: 724–729

Hafström O, Milerad J, Asokan N, Poole SD, Sundell HW 2000 Nicotine delays arousal during hypoxemia in sleeping lambs. Pediatr Res 47: 646–652

Milerad J, Larsson H, Lin J, Lindstrom DP, Sundell HW 1996 Breath-by-breath determinations of airway occlusion pressure in the developing lamb. Eur J Appl Physiol 74: 44–51

Hariharan M, VanNoord T, Greden JF 1988 A high-performance liquid-chromatographic method for routine simultaneous determination of nicotine and cotinine in plasma. Clin Chem 34: 724–729

Grogaard J, Sundell HW 1983 Effect of beta-adrenergic agonists on apnea reflexes in newborn lambs. Pediatr Res 17: 213–219

Slotkin TA, Saleh JL, McCook EC, Seidler FJ 1997 Impaired cardiac function during postnatal hypoxia in rats exposed to nicotine prenatally: implications for perinatal morbidity and mortality, and for sudden infant death syndrome. Teratology 55: 177–184

Slotkin TA, Lappi SE, McCook EC, Lorber BA, Seidler FJ 1995 Loss of neonatal hypoxia tolerance after prenatal nicotine exposure: implications for sudden infant death syndrome. Brain Res Bull 38: 69–75

Svensson TH, Engberg G 1980 Effect of nicotine on single cell activity in the noradrenergic nucleus locus coeruleus. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl 479: 31–34

Andersson K, Fuxe K, Eneroth P, Mascagni F, Agnati LF 1985 Effects of acute intermittent exposure to cigarette smoke on catecholamine levels and turnover in various types of hypothalamic DA and NA nerve terminal systems as well as on the secretion of adenohypophyseal hormones and corticosterone. Acta Physiol Scand 124: 277–285

Andersson K, Eneroth P, Fuxe K, Mascagni F, Agnati LF 1985 Effects of chronic exposure to cigarette smoke on amine levels and turnover in various hypothalamic catecholamine nerve terminal systems and on the secretion of pituitary hormones in the male rat. Neuroendocrinology 41: 462–466

Svensson TH, Grenhoff J, Engberg G 1990 Effect of nicotine on dynamic function of brain catecholamine neurons. Ciba Found Symp 152: 169–180

Donnelly DF, Sica AL, Cohen MI, Zhang H 1989 Dorsal medullary inspiratory neurons: effects of superior laryngeal afferent stimulation. Brain Res 491: 243–252

de Burgh Daly M, Korner PI, Angell-James JE, Oliver JR 1978 Cardiovascular-respiratory reflex interactions between carotid bodies and upper-airways receptors in the monkey. Am J Physiol 234: H293–H299

Jacobi MS, Thach BT 1989 Effect of maturation on spontaneous recovery from hypoxic apnea by gasping. J Appl Physiol 66: 2384–2390

Lawson EE, Thach BT 1977 Respiratory patterns during progressive asphyxia in newborn rabbits. J Appl Physiol 43: 468–474

St John WM 1996 Medullary regions for neurogenesis of gasping: noeud vital or noeuds vitals?. J Appl Physiol 81: 1865–1877

Ramirez JM, Schwarzacher SW, Pierrefiche O, Olivera BM, Richter DW 1998 Selective lesioning of the cat pre-Botzinger complex in vivo eliminates breathing but not gasping. J Physiol (Lond) 507: 895–907

Schuen JN, Bamford OS, Carroll JL 1997 The cardiorespiratory response to anoxia: normal development and the effect of nicotine. Respir Physiol 109: 231–239

Fewell JE, Smith FG 1998 Perinatal nicotine exposure impairs ability of newborn rats to autoresuscitate from apnea during hypoxia. J Appl Physiol 85: 2066–2074

Gershan WM, Jacobi MS, Thach BT 1992 Mechanisms underlying induced autoresuscitation failure in BALB/c and SWR mice. J Appl Physiol 72: 677–685

Froen JF, Akre H, Stray-Pedersen B, Saugstad OD 2000 Adverse effects of nicotine and interleukin-1β on autoresuscitation after apnea in piglets: implications for sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatrics 105: E52: 1–5

Lieske SP, Thoby-Brisson M, Telgkamp P, Ramirez JM 2000 Reconfiguration of the neural network controlling multiple breathing patterns: eupnea, sighs and gasps. Nat Neurosci 3: 600–607

Ueda Y, Stick SM, Hall G, Sly P 1999 Control of breathing in infants born to smoking mothers. J Pediatr 135: 226–232

Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA 1986 Non-neurogenic adrenal catecholamine release in the neonatal rat: exocytosis or diffusion?. Brain Res 393: 274–277

Lanier B, Richarson MA, Cummings C 1983 Effect of hypoxia on laryngeal reflex apnea: implications for sudden infant death. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 91: 597–604

Benowitz NL 1986 Clinical pharmacology of nicotine. Ann Rev Med 37: 21–32

Jacob P, Benowitz NL, Shulgin AT 1988 Recent studies of nicotine metabolism in humans. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 30: 249–253

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Robert A. Parker for valuable assistance with statistical analysis, Dr. M. Hariharan for performing nicotine and cotinine determinations, Patricia A. Minton, R.N., Rao Gaddipati, M.S., and Stanley D. Poole, M.S., for skilled technical assistance, and Donna Staed for typing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (HD 28916 and HL 14214) and by the Swedish Medical Research Council (J.M.).These results were presented in part at the annual meeting of the American Pediatric Society and Society for Pediatric Research 1994.Current address (H.K.): Centennial Medical Center/Women's Center, 2300 Patterson Street, Nashville, TN 37203, U.S.A.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sundell, H., Karmo, H. & Milerad, J. Impaired Cardiorespiratory Recovery after Laryngeal Stimulation in Nicotine-Exposed Young Lambs. Pediatr Res 53, 104–112 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-200301000-00018

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-200301000-00018