Abstract

Rises in fetal adenosine during hypoxia may have a metabolic inhibitory role that helps the fetus adapt to periods of low arterial partial pressure of oxygen (Pao2). We examined the fetal cerebral hemodynamic and metabolic responses to exogenous adenosine infusion and compared this with previous studies. Six fetal sheep at ca. 125 d gestation were instrumented under general anesthesia with catheters, flow probes, and near-infrared optodes and allowed to recover. After 3 d, adenosine was infused at a level known to reproduce fetal levels during hypoxia. Fetal hemodynamics and cerebral near-infrared spectroscopic (NIRS) variables were monitored and paired blood samples taken for oxygen delivery and consumption calculation. Fetal heart rate, mean arterial pressure, and carotid flow showed no change during adenosine infusion. Cerebral oxyhemoglobin (HbO2), deoxyhemoglobin (Hb), and blood volume rose, suggesting venous pooling in the brain. Cerebral cytochrome oxidase (CcO) became more oxidized, indicating reduction in electron flow down the mitochondrial electron transfer chain and, thus, a fall in metabolic rate. Blood sample analysis revealed that there was no change in oxygen delivery to the head but that cerebral oxygen consumption fell during adenosine infusion. These data indicate that fetal cerebral metabolism fell during infusion of adenosine at a level known to reproduce fetal plasma concentrations during hypoxia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Adenosine is a vasoactive purine metabolite produced during breakdown of high-energy phosphates in hypoxia. Tissue levels of adenosine are 2–3 times higher in the fetus than the adult (1) and have been shown to rise further within minutes of the onset of hypoxia in the ovine fetus (2). Plasma adenosine levels are also higher in hypoxemic, acidotic growth-retarded human fetuses than in appropriately grown fetuses (3). This may be seen as a direct consequence of the hypoxemia, but there is also the possibility that elevated tissue and plasma adenosine may form part of a protective fetal adaptation aimed at matching oxygen demand to availability (4, 5). Adenosine acting via A2 receptors is known to cause vasodilatation both in the peripheral and cerebral vascular beds, which improves cerebral blood flow and, thus, cerebral DO2(6, 7). Adenosine also inhibits fetal breathing and eye and body movements, depresses excitatory neurotransmission, and causes neuronal hyperpolarization, all of which will reduce fetal V˙O2(8, 9).

We have previously reported that mild hypoxemia in the ovine fetus is associated with an increase in CBV and in the cerebral concentration of CcO as measured by near-infrared spectroscopy (10). We hypothesize that these changes are the result of the dual actions of endogenous adenosine on cerebral blood vessels and on cerebral metabolism. The aim of this study was, therefore, to determine whether adenosine administered exogenously to the chronically instrumented ovine fetus in utero would lead to similar changes in CBV and CcO redox state as those observed during moderate hypoxemia.

METHODS

Surgical preparation and fetal surgery.

All work was conducted in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (1986) on ewes bearing singleton near-term fetuses (ca. 123 d gestation). The surgical procedure has been described previously (10). Briefly, six date-mated Romney Marsh ewes bearing singleton fetuses were operated on under aseptic conditions. Catheters were placed in the fetal brachial artery and jugular vein and a transonic flow probe was placed around the contralateral carotid artery. A pair of electrodes was sewn onto the chest wall for monitoring of fetal ECG (Cooner Wire Corp., Chatsworth, CA, U.S.A.). By use of a T incision, the skin of the scalp was peeled back. Burr holes were made in the skull overlying the parasagittal cortex, and electrodes were placed on the dura to allow monitoring of electrocortical activity. The burr holes were sealed using rubber caps and cyanoacrylate. Infrared optodes were placed on the skull overlying the parasagittal cortex and held firmly in place by molded black rubber holders sutured to the edges of the skin incision. Apposition of optodes to scalp was improved further when the scalp incision was closed over the holders and optodes. The fetus was replaced and the uterus closed in two layers. The maternal abdomen was closed and the ewe allowed to recover after placement of a catheter in the maternal recurrent metatarsal vein for administration of antibiotics.

Animal maintenance and antibiotic regime.

Ewes were held in metabolic carts for the duration of the study and had access to water and hay ad libitum. Before surgery, the ewe was given prophylactic Streptapen 1 g i.m. After the surgery, the following antibiotics were given each morning: Crystapen 150 mg to the amniotic cavity, 300 mg i.v. to the ewe, and 150 mg i.v. to the fetus for 5 d and Cidomicin 40 mg to the amniotic cavity, 40 mg to the ewe i.v. for 2 d. A fetal arterial blood sample was taken each morning before giving the antibiotic regime and tested for gases and electrolytes with a BGE machine (BG Electrolytes 14008–01 and Co-Oximeter 482, Instrumentation Laboratories, UK).

Infusion protocol.

On the basis of data describing the hemodynamic response to various doses of exogenous adenosine, we chose to infuse adenosine at a rate of 3 μmol·kg−1·min −1 into the jugular vein toward the heart. This dose has been shown to reproduce similar systemic levels to those observed in the fetus during hypoxia, i.e. in the range 4–6 μM when Pao2 is ∼ 12–15 mm Hg (8). In addition, it does not produce large hemodynamic changes that could interfere with the metabolic mechanisms being investigated in this study. Each infusion lasted 20 min and was succeeded by saline infusion.

Data collection.

Experiments were performed on either d 2 or 3 after surgery. Hemodynamic and near-infrared spectroscopic (NIRS) data were collected for 1 h before, during, and after adenosine infusion.

Arterial and central venous pressures (SensoNor pressure transducers, Horten, Norway, and Digitimer Ltd. amplifiers, Welwyn Garden City, UK) were corrected for amniotic pressure and monitored by use of MacLab software (AD Instruments, UK). Fetal heart rate and carotid flow were monitored using MacLab software and saved to disk for off-line analysis. The electrocorticogram (ECoG) signal was monitored to confirm normal cerebral function by the presence of sleep-state cycling.

Blood samples were collected at −5, +5, +20, and +50 min relative to the start of a 20-min adenosine infusion. At each time point, 0.5-mL samples were collected from carotid artery and jugular vein. Samples were immediately tested for gases and electrolytes (BGE machine as above) and for glucose and lactate (YSI 2300 STAT Plus), temperature corrected to fetal temperature of 39.5°C.

DO2 values were calculated as the product of carotid flow (Q) and carotid arterial oxygen content (Ca) corrected to 39.5°C. V˙O2 values were calculated using the appropriate venous oxygen content (Cv) and Fick's law:

MATH

NIRS data analysis.

The use of and reliability of this technique have been discussed previously (10) and are not discussed in detail here. Briefly, spectra were saved to disk for off-line analysis. Absolute changes in chromophore concentration were calculated by subtracting from the reference spectrum (spectrum at time zero), then fitting between 780 and 900 nm to previously determined individual chromophore absorption spectra by using a least-squares multilinear regression algorithm (11, 12). Residual changes in OD, not accounted for in the fitting process, were analyzed for the presence of large or systematic changes that might indicate the presence of another chromophore not included in the algorithm. In addition, large changes in optical path length during measurements were excluded using 2nd-order differential analysis from the 840-nm water-absorption feature (13).

Changes in the cerebral concentration of HbO2 and Hb are expressed in μmol/L from a zero set at the start of the experiment. Because CcO concentration does not change over the time scale of the experiment, changes in the CcO signal represent changes in the amount of the oxidized enzyme present relative to the start of the experiment and not to changes in enzyme levels. A value for changes in total Hb concentration (Δ[tHb]) was generated from the sum of Δ[HbO2] and Δ[Hb] at any time point. tHb is related to blood volume through the hematocrit.

Data presentation and statistical methods.

We obtained data from six fetal sheep. All data are expressed as mean ± SE;n = 6 for all variables except where stated. Time points taken for analysis are −5, +5, +20, and +50 min relative to the start of infusion. Repeated-measures ANOVA with Newman-Keuls post hoc tests were used to compare multiple data points with control (−5 min). In the case of DO2 and V˙O2, unpaired t test was used to compare the preinfusion data with that after treatment. Owing to either missing CaBF or oxygen content data, there are too few data points in the recovery phase to analyze DO2 or V˙O2 confidently, and we have concentrated instead on analyzing the effect of adenosine treatment. Statistical significance is taken as p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Hemodynamics, blood gases, and acid-base status.

The effect of adenosine infusion on fetal hemodynamics, Pao2, Paco2, pHa, glucose, and lactate is shown in Table 1. Although there were no significant changes in hemodynamic variables during or after infusion, the tendency for mean arterial pressure (MAP) to fall and for CaBF to rise is consistent with the known vasodilatory properties of adenosine.

DO2 and V˙O2.

Figure 1 shows that there was no change in DO2 to the fetal head during adenosine infusion. At the end of the 20-min infusion, however, V˙O2 had fallen significantly from 1.29 ± 0.21 to 0.64 ± 0.09 mL O2/min (p < 0.05, unpaired t test versus −5 min).

Data for DO2, (left pair of columns) and V˙O2(right pair of columns) across the head before (left column) and at the end of a 20-min infusion of adenosine at 3 μmol·kg−1·min−1 (right column). Whereas DO2 did not increase, there was a statistically significant fall in V˙O2 by the end of the treatment. *p < 0.05, paired t test vs preinfusion level.

Changes in concentration of HbO2 and Hb.

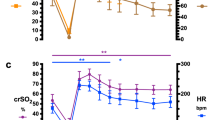

Typical changes in cerebral HbO2 and Hb during adenosine infusion are shown in Figure 2 (upper panel). They show how Hb begins to rise some time before HbO2. Mean data for the group are shown in Figure 3 (upper panel) and reflect the different timing of changes in these two chromophores. Mean Hb can be seen to rise to a maximal value of 14.2 ± 2.5 μmol/L (p < 0.05, repeated-measures ANOVA with Newman-Keuls post hoc test, n = 6). HbO2 started to rise after Hb and attained a maximal value of 9.0 ± 2.4 μmol/L above control (p < 0.05, test as for Hb). Both Hb and HbO2 were not different from preinfusion levels 30 min after cessation of the infusion.

Raw NIRS data for changes in concentration of HbO2 and Hb (upper panel) and for tHb and CcO (lower panel). HbO2 begins to increase approximately 7 min after the initial increase in Hb at the same time that Hb begins to fall. This results in a biphasic tHb response (lower panel). CcO increases slowly throughout the period of the infusion (bar).

Typical NIRS data during infusion of adenosine at 3 μmol·kg−1·min−1. The upper panel shows that Hb begins to increase before HbO2. Therefore, the initial increase in blood volume (lower panel, right) is due to an increase in deoxygenated blood only. There is a significant increase in CcO by the end of the infusion period (lower panel, left).

Changes in tHb.

Figure 2 (lower panel) shows typical data for change in tHb, which is equivalent to CBV. This variable rose rapidly after the start of the infusion period, then slowly increased for the duration of the infusion. The group mean data in Figure 3 (lower panel, right) show that the tHb reached a maximal value of 18.3 ± 3.5 μmol/L above control by the end of the infusion period (p < 0.05, repeated-measures ANOVA with Newman-Keuls post hoc test). tHb fell back toward control levels after the end of adenosine infusion and was not different from control levels 30 min later.

Changes in CcO.

Typical changes in oxidation of CcO are shown in Figure 2 (lower panel). CcO rose slowly for the duration of the adenosine infusion before falling back toward baseline after cessation of the infusion. Group mean data are shown in Figure 3 (lower panel, left). Mean CcO rose to a maximum of 0.48 ± 0.01 μmol/L above control by the end of infusion (p < 0.05, repeated-measures ANOVA with Newman-Keuls post hoc test). CcO oxidation was not different from control 30 min after cessation of infusion.

DISCUSSION

Fetal adenosine levels are known to increase during episodes of hypoxia, and it has been suggested that adenosine may be neuroprotective under these circumstances (14). There are several mechanisms by which this could be achieved. Adenosine causes cerebral vasodilatation, which may lead to an increase in cerebral blood flow and so maintain DO2. In addition, adenosine has metabolic inhibitory actions that could reduce V˙O2, the overall result being to match oxygen supply and demand. Both of these aspects are addressed in this study, which describes the effect of exogenous adenosine, given in amounts that have been reported to bring plasma adenosine to similar levels to those seen in hypoxia, on fetal cerebral hemodynamics and metabolism.

The cardiovascular effects of adenosine include a myocardial A1 receptor-mediated bradycardia and, at higher concentrations, an A2 receptor-mediated vasodilatation of both cerebral and peripheral vessels (15). We deliberately chose to infuse adenosine at a rate that would not markedly alter fetal systemic hemodynamics, and, although there was a tendency for MAP to fall and for CaBF to rise, changes in fetal hemodynamics were not statistically significant. We did, however, observe a rise in total cerebral Hb concentration measured by NIRS. tHb is derived from the sum of HbO2 and Hb measured in all three vascular compartments and is directly related to CBV. The increase in CBV observed indicates that there was a functional cerebral vasodilatation during adenosine infusion as suggested by the hemodynamic variables. The absence of any statistically significant change in CaBF in this study group might suggest that adenosine did not have a significant effect on the arterial side of the circulation, although small changes in regional cerebral blood flow will not be detected by measurements of carotid blood flow, and we cannot say that significant differences would not emerge with a larger study group. As the major part of CBV is located in the venous circulation, it is likely that venous dilatation will dominate the changes observed here. This could result from a direct effect of adenosine on vessels, a diminution of venous outflow if venous pressure were increased secondary to increased cardiac afterload, or reduced venous return after fetal bradycardia.

Although these data do not show an increase in cerebral DO2 with exogenous adenosine, we did observe a significant fall in V˙O2, indicating a decrease in cerebral metabolism. Karimi et al. (8) also demonstrated a fall in V˙O2 during adenosine infusion, although these were data from a whole-body preparation and did not explore regional variations in metabolic response. There is, in addition, a growing body of evidence from animal models suggesting that adenosine reduces metabolic rate during and after hypoxia-ischemia (4, 16–18).

There are a variety of mechanisms by which adenosine could reduce whole-body V˙O2. Adenosine is involved in the reduction in fetal breathing movements observed during hypoxia (19), and, because these body movements account for 17% of fetal whole-body V˙O2(20), their cessation provides a substantial energy saving. Mechanisms specific to the fall in cerebral metabolism observed in this study include a reduction in glutamate-mediated excitatory neurotransmission (21, 22) and neuronal hyperpolarization (23). Both of these actions of adenosine would promote the reduction in electron flow down the mitochondrial electron transfer chain through reducing ATP use for plasma membrane repolarization after action potential firing, thus reducing energy demand. In addition to any potential direct actions of adenosine on metabolic rate, by reducing energy demand in this way, adenosine may promote a rise in ATP levels that could act at upstream inhibitory sites (possibly at phosphofructokinase) to inhibit the electron transfer chain further. Such inhibition may result in the shunting of pyruvate into lactate production, which may account for the tendency seen in this experiment, also shown by others (8), for lactate levels to rise during normoxemic infusion of adenosine.

Metabolic information can also be derived from the NIRS CcO signal. Both the use of NIRS to provide metabolic information via the CcO signal and the sensitivity of the method are well established (24). The CcO signal gives information about the oxidation state of the mitochondrial population interrogated by the incident near infrared light. CcO is the final electron acceptor in the mitochondrial electron transfer chain, and its redox state is influenced by three factors:1) the flow of reducing equivalents from the tricarboxylic acid cycle, 2) the rate of transfer of electrons from cytochrome c, and 3) the availability of oxygen at the oxygen-binding site. Despite unchanged oxygen delivery to the head during adenosine infusion, there was a significant increase in brain CcO oxidation by the end of the infusion period. This increase in CcO oxidation was similar in magnitude and direction to that previously reported during asphyxia in late-gestation fetal sheep (10). During both hypoxia and adenosine infusion, the redox state of CcO does not appear to be influenced by DO2; in the former, DO2 fell, and, in the latter, it stayed stable, and yet in both instances, CcO became more oxidized.

NO is a possible link between adenosine and alterations in oxidative phosphorylation. Adenosine increases NO release from astrocytes (25), and NO is known to interact with components of the mitochondrial electron transfer chain (26). NO can inhibit metabolism both reversibly and irreversibly (27, 28); the reversible inhibition is due to competition between NO and O2 for the cytochrome oxidase binuclear center, the site at which molecular oxygen is reduced to water. Because this is a competitive inhibition, NO effects are greater a) when Po2 is low and b) when NO is high, both of which may be the case during profound hypoxia. Irreversible inhibition, however, occurs when mitochondria are exposed to high NO levels for several hours. In this instance, the inhibition is due to permanent nitrosylation of protein thiols in mitochondrial complex I and removal of iron from iron-sulfur centers. However, from our present knowledge, it seems unlikely that transient alterations in NO concentration could result in mitochondrial oxidation as observed in this study. The effect of reversible inhibition on cellular redox would be to allow electrons to build up in the transfer chain and cause reduction of the CuA moiety rather than the oxidation reported here. Whereas irreversible inhibition would block electron transfer at complex 1 and lead to CuA oxidation, it is unlikely that this could occur within the short time course (20 min) of this experiment. In addition, the redox state of CuA returned to baseline levels within 30 min after stopping adenosine infusion.

A mechanism that could account for CcO oxidation during asphyxia is suggested by data from Yager et al. (29), who calculated CcO redox state using the acetoacetate/β-hydroxybutyrate substrate couple. In their experiments, hypoxia-ischemia caused a reduction followed by an oxidation of mitochondrial redox. They suggest that a reduction in the flow of reducing equivalents, not low oxygen delivery, is the limiting factor in respiration during severe hypoxia in immature animals. If this is the case, it would explain our previous findings during asphyxia (10) and, combined with the data presented here, suggest that an increase in endogenous adenosine occurring during hypoxia may decrease the flow of reducing equivalents down the oxidative phosphorylation pathway and so lead to a decrease in cerebral metabolism.

Our data demonstrate that infusion of adenosine in the late-gestation ovine fetus results in a fall in cerebral metabolism similar to that observed previously during asphyxia. There is now circumstantial evidence to suggest that adenosine acts as an endogenous neuroprotective agent in the immature brain. However, further work using pharmacologic interventions to augment or block the endogenous adenosine response to hypoxia, coupled with measurement of sequelae in terms of neural structure and function, will be needed to clarify whether adenosine is indeed neuroprotective.

Abbreviations

- CaBF:

-

carotid artery blood flow

- CBV:

-

cerebral blood volume

- CcO:

-

oxidized cytochrome oxidase

- CuA:

-

copper A moiety of cytochrome oxidase

- DO2:

-

oxygen delivery

- Hb:

-

deoxyhemoglobin

- HbO2:

-

oxyhemoglobin

- NO:

-

nitric oxide

- Pao2:

-

arterial Po2

- tHb:

-

total Hb

- V˙o2:

-

oxygen consumption

References

Sawa R, Asakura H, Power GG 1991 Changes in plasma adenosine during simulated birth of fetal sheep. J Appl Physiol 70: 1524–1528

Kubonoya K, Power GG 1997 Plasma adenosine responses during repeated episodes of umbilical cord occlusion. Am J Obstet Gynecol 177: 395–401

Yoneyama Y, Wakatsuki M, Sawa R, Kamoi S, Takahashi H, Shin S, Kawamura T, Power GG, Araki T 1994 Plasma adenosine concentration in appropriate- and small-for-gestational-age fetuses. Am J Obstet Gynecol 170: 684–688

Rudolphi KA, Schubert P, Parkinson FE, Fredholm BB 1992 Neuroprotective role of adenosine in cerebral ischaemia. Trends Pharmacol Sci 13: 439–445

Gidday JM, Fitzgibbons JC, Shah AR, Kraujalis MJ, Park TS 1995 Reduction in cerebral ischemic injury in the newborn rat by potentiation of endogenous adenosine. Pediatr Res 38: 306–311

Kurth CD, Wagerle LC 1992 Cardiovascular reactivity to adenosine analogues in 0.6–0.7 gestation and near-term fetal sheep. Am J Physiol 262: H1338–H1342

Laudignon N, Farri E, Beharry K, Rex J, Aranda JV 1990 Influence of adenosine on cerebral blood flow during hypoxic hypoxia in the newborn piglet. J Appl Physiol 68: 1534–1541

Karimi A, Ball KT, Power GG 1996 Exogenous infusion of adenosine depresses whole body O2 use in fetal/neonatal sheep. J Appl Physiol 81: 541–547

de Mendonca A, Ribeiro JA 1993 Adenosine inhibits the NMDA receptor-mediated excitatory postsynaptic potential in the hippocampus. Brain Res 606: 351–356

Newman JP, Peebles DM, Harding SRG, Springett R, Hanson MA 2000 Hemodynamic and metabolic responses to moderate asphyxia in brain and skeletal muscle of late-gestation fetal sheep. J Appl Physiol 88: 82–90

Matcher SJ, Elwell CE, Cooper CE, Cope M, Delpy DT 1995 Performance comparison of several published tissue near-infrared spectroscopic algorithms. Anal Biochem 227: 54–68

Wray S, Cope M, Delpy DT, Wyatt JS, Reynolds EOR 1988 Characterisation of the near infrared absorption spectra of cytochrome aa3 and haemoglobin for the noninvasive monitoring of cerebral oxygenation. Biochim Biophys Acta 933: 184–192

Cooper CE, Elwell CE, Meek JH, Matcher SJ, Wyatt JS, Cope M, Delpy DT 1996 The noninvasive measurement of absolute cerebral deoxyhemoglobin concentration and mean optical path length in the neonatal brain by second derivative near infrared spectroscopy. Pediatr Res 39: 32–38

Ongini E, Adami M, Ferri C, Bertoerelli R 1997 Adenosine A2A receptors and neuroprotection. Ann N Y Acad Sci 825: 30–48

Koos BJ, Chau A 1998 Fetal cardiovascular and breathing responses to an adenosine A2 receptor agonist in sheep. Am J Physiol 274: R152–R159

Marks KA, Mallard CE, Roberts I, Williams CE, Gluckman PD, Edwards AD 1996 Nitric oxide synthase inhibition attenuates delayed vasodilation and increases injury after cerebral ischemia in fetal sheep. Pediatr Res 40: 185–191

Kamii H, Mikawa S, Murakami K, Kinouchi H, Yoshimoto T, Reola L, Carlson E, Epstein CJ, Chan PH 1996 Effects of nitric oxide synthase inhibition on brain infarction in SOD-1-transgenic mice following transient focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 16: 1153–1157

Kawahara N, Ide T, Saito N, Kawai K, Kirino T 1998 Propentofylline potentiates induced ischemic tolerance in gerbil hippocampal neurons via adenosine receptor. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 18: 472–475

Koos BJ, Doany W 1991 Role of plasma adenosine in breathing responses to hypoxia in fetal sheep. J Dev Physiol 16: 81–85

Rurak DW, Gruber NG 1983 The effect of neuromuscular blockade on oxygen consumption and blood gases in the fetal lamb. J Dev Physiol 145: 258–262

Dolphin AC, Archer ER 1983 An adenosine agonist inhibits and a cyclic AMP analogue enhances the release of glutamate but not GABA from slices of rat dentate gyrus. Neurosci Lett 43: 49–54

Corradetti R, Lo Conte G, Moroni F, Passani MB, Pepeu G 1984 Adenosine decreases aspartate and glutamate release from rat hippocampal slices. Eur J Pharmacol 104: 19–26

Dunwiddie TV, Fredholm BB 1989 Adenosine A1 receptors inhibit adenylate cyclase activity and neurotransmitter release and hyperpolarize pyramidal neurons in rat hippocampus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 249: 31–37

Cooper CE, Springett R 1997 Measurement of cytochrome oxidase and mitochondrial energetics by near-infrared spectroscopy. Philos Trans R Soc Lond 352: 669–676

Janigro D, Wender R, Ransom G, Tinklepaugh DL, Winn HR 1996 Adenosine-induced release of nitric oxide from cortical astrocytes. Neuroreport 7: 1640–1644

Brown CG 1999 Nitric oxide and mitochondrial respiration. Biochim Biophys Acta 1411: 351–369

Clementi E, Brown CG, Feelisch M, Moncada S 1998 Persistent inhibition of cell respiration by nitric oxide: crucial role of S-nitrosylation of mitochondrial complex I and protective action of glutathione. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 7631–7636

Clementi E, Brown CG, Foxwell N, Moncada S 1999 On the mechanism by which vascular endothelial cells regulate their oxygen consumption. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 1559–1562

Yager JY, Brucklacher RM, Vannucci RC 1996 Paradoxical mitochondrial oxidation in perinatal hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. Brain Res 712: 230–238

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supported by SPARKS.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Newman, J., Peebles, D. & Hanson, M. Adenosine Produces Changes in Cerebral Hemodynamics and Metabolism as Assessed by Near-Infrared Spectroscopy in Late-Gestation Fetal Sheep in Utero. Pediatr Res 50, 217–221 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-200108000-00009

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-200108000-00009