Abstract

Background:

Contemporary therapies for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) have shown survival improvements, which do not account for patient experience and health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Methods:

This literature review included a search of MEDLINE for randomized clinical trials enrolling ⩾50 patients with mCRPC and reporting on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) since 2010.

Results:

Nineteen of 25 publications describing seven treatment regimens (10 clinical trials and nine associated secondary analyses) met the inclusion criteria and were critically appraised. The most commonly used measures were the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostate (n=5 trials) and Brief Pain Inventory Short Form (n=4 trials) questionnaires. The published data indicated that HRQoL and pain status augmented the clinical efficacy data by providing a better understanding of treatment impact in mCRPC. Abiraterone acetate and prednisone, enzalutamide, radium-223 dichloride and sipuleucel-T offered varying levels of HRQoL benefit and/or pain mitigation versus their respective comparators, whereas three treatments (mitoxantrone, estramustine phosphate and docetaxel, and cabazitaxel) had no meaningful impact on HRQoL or pain. The main limitation of the data were that the PROs utilized were not developed for use in mCRPC patients and hence may not have comprehensively captured symptoms important to this population.

Conclusions:

Recently published randomized clinical trials of new agents for mCRPC have captured elements of the patient experience while on treatment. Further research is required to standardize methods for measuring, quantifying and reporting on HRQoL and pain in patients with mCRPC in the clinical practice setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed malignancy in the United States (after breast and lung), with an estimated 220 800 new cases and 27 540 deaths in 2015.1Most patients present with localized disease and undergo initial surgical and/or radiological therapy, with concomitant or subsequent use of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). Generally, PSA level should be <0.5 ng ml−1 after radiation therapy and <0.2 ng ml−1 after a radical prostatectomy,2 and occurrence of two consecutive PSA level elevations is often considered biochemical recurrence or progression to stage D1.5 disease. Biochemical recurrence develops in ≈10% of low-risk and up to 60% of high-risk prostate cancer patients after external beam radiation therapy3, 4, 5, 6 and in 20–30% of patients after radical prostatectomy7, 8, 9 despite use of ADT.

Once prostate cancer has become metastatic, ADT is deployed and is highly effective, eliciting a response in most cases; however, resistance inevitably develops, resulting in transition to a lethal castration-resistant phenotype, affecting 10–20% of prostate cancer patients within 5 years,10 and the death of >50% of patients within 3 years with historical standard therapies.11, 12, 13, 14, 15 This end of the disease continuum is termed metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), defined by cancer progression despite a testosterone level of <50 ng dl−1 (<1.7 nmoll−1).16

The natural history of mCRPC can involve worsening symptomatology represented by a progressive decline in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and worsening pain,10 where HRQoL is considered a multidomain phenomenon capturing an individual’s perceived mental, emotional, physical and social well-being over time.17, 18 The first treatments approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for mCRPC management focused on the palliative benefits of pain control achieved by mitoxantrone, strontium and samarium.19, 20, 21 In 2004, docetaxel became standard of care after two phase III trials demonstrated a survival benefit over mitoxantrone.12, 13 Data from one of these trials13 showed that global HRQoL improved from baseline to 6 months in patients receiving docetaxel despite similar rates of pain relief in both groups,22 suggesting that pain relief is only a component of HRQoL in mCRPC, as fatigue and physical function (upon which pain can have an impact) are also major contributors. Certainly, asymptomatic patients are more likely to have worsening HRQoL after cytotoxic chemotherapy treatment,23 and this risk must be weighed against potential benefits.

Since 2010, a fundamental shift has occurred in the mCRPC treatment landscape with the arrival of immunotherapy (sipuleucel-T (sip-T)), agents targeting androgen signaling (abiraterone acetate and enzalutamide), and a bone-targeting radiopharmaceutical (radium-223 dichloride), which extend survival when utilized before or after docetaxel chemotherapy.24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 Median overall survival (OS) among patients with nonvisceral mCRPC who received immunotherapy with sip-T was 25.8 versus 21.7 months in the placebo group.26 In patients with mCRPC before and after chemotherapy, respectively, targeted therapy with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone (OS, 34.7 vs 30.3 months and 15.8 vs 11.2 months),25, 31 enzalutamide (OS, 32.4 vs 30.2 months and 18.4 vs 13.6 months),24, 30 and radium-223 dichloride (OS, 16.1 vs 11.5 months and 14.4 vs 11.3 months)32 all increased OS relative to control. Additional cytotoxic therapy with cabazitaxel was found to extend OS (15.1 vs 12.7 months) in men whose mCRPC had progressed after docetaxel therapy, when compared with the prior palliative standard of mitoxantrone.33 The life-extending noncytotoxic therapies in particular have potential to have a favorable impact on patients’ HRQoL and pain and may strike a better balance between cancer control and toxicity.

In response to the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 2 proposed principles of conduct for phase II and III mCRPC trials, the clinical trials of these new therapies evaluated patient-reported outcomes (PROs) to ensure that the overall efficacy and safety profiles of new therapies reflect patient experience and perceptions.16, 34 The US Food and Drug Administration defines a PRO as ‘any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.’17 PRO instruments typically include information about HRQoL, symptoms, function, satisfaction with care or symptoms, adherence to prescribed medications or other therapy, and perceived value of treatment.18 In the prostate cancer setting, multiple instruments have included specific symptoms relevant to the disease (for example, urinary control and hot flashes), the most widely used being the multidimensional Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostate (FACT-P) questionnaire, which indicates a worsening or improving HRQoL when the total score changes by at least 6–10 points on a 0–156 scale.35

Here we review PRO data from clinical trials of patients with mCRPC reported since 2010 in order to contextualize the overall impact of new treatment modalities from the patient’s perspective, and in so doing, guide patient-centered care, clinical decision-making, and health policy decisions.

Patients and Methods

To review clinical trials reporting PROs in patients with mCRPC, we conducted two separate searches of the US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health Medline database for full articles published between January 2010 and April 2015. We first created a database of all randomized, controlled trial articles in mCRPC using the following Boolean search term strategy: (prostate cancer) AND (castration-resistant OR hormone-refractory OR androgen independence) AND (randomized OR randomised). A second search was conducted as follows: (prostate cancer) AND (health-related quality of life OR HRQoL OR QoL) OR pain OR fatigue OR weight loss. Both searches were limited to articles published in English and combined to create the full data set of potentially eligible articles. Additional references were identified from bibliographies of published articles.

We screened the title and abstract of each retrieved article for relevance against predefined inclusion criteria: clinical studies in mCRPC with a sample size ⩾50. We qualitatively reviewed full text articles for final inclusion and assessment based on the following endpoints of interest: change from baseline in PRO scores; time to improvement or deterioration in a PRO measure; and proportion of patients with improvement or deterioration in a PRO measure.

Results

We identified 26 publications meeting our predefined inclusion criteria. Six were excluded because the therapies described are not used in standard clinical practice.36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 Nineteen publications describing seven treatment regimens (ten clinical trials and ten associated secondary analyses) were reviewed (Table 1).

PRO Instruments

Across the 10 clinical trials, 7 different patient-completed questionnaires measuring HRQoL and/or pain were used. All PROs had demonstrated reliability, had been subject to validation processes, were responsive to change in health state, and had well-established psychometric characteristics although the Pain Index has not been subject to same validation processes as far as we are aware (Table 2). In the identified trials, HRQoL instruments were most often used along with a separate pain instrument. The two most commonly used PROs were the FACT-P questionnaire (used in five of the trials),42, 43, 44 and the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) Short Form (SF; used in four of the trials).45 Three of the trials did not use an HRQoL instrument and only used pain instruments.33, 46, 47 These trials and one other collected data regarding use of analgesics, specifically opiate medications.46, 47, 48, 49 Conversely, two trials did not use a dedicated pain instrument and used an HRQoL instrument only.50, 51 The PREVAIL study (Table 1) used two complementary tools to evaluate HRQoL: the prostate-cancer-specific FACT-P questionnaire and the generic EQ-5D questionnaire.52 Both the PREVAIL and AFFIRM studies reported on pain using the FACT-P prostate cancer subscale (PCS) pain-related items, which complemented utilization of the BPI-SF.52 Patient-reported fatigue was reported in three studies: one utilized the Brief Fatigue Inventory (COU-AA-301)53 and the others utilized the fatigue symptom scale questionnaire of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ)-C30.49, 51 Studies reporting FACT-P total and PCS scores included items addressing fatigue but, to date, no results have been published on fatigue domains of FACT-P scores specifically.

Treatment-related changes in PROs

Most studies reported time-to-event analyses (for example, time to improvement or deterioration in FACT-P total score) by use of Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and/or the proportion of patients with clinically meaningful improvement in a PRO score. Changes from baseline in mean scores for a particular PRO measure were not reported routinely.

Abiraterone acetate

Two registrational, placebo controlled, phase III studies of abiraterone acetate in mCRPC examined HRQoL and pain in patients progressing after docetaxel chemotherapy (COU-AA-301) and before docetaxel chemotherapy (COU-AA-302) despite ongoing ADT.29, 54 Patient compliance rates with PRO questionnaires were high during both studies.28, 53, 55, 56, 57

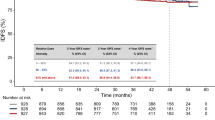

In COU-AA-301, patients had mean baseline FACT-P total scores approximating 108 of the maximum possible score of 156, indicating that these patients had a moderate level of HRQoL impairment.55 Changes in estimated FACT-P total score from baseline to week 112 favored the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone arm over the placebo plus prednisone arm throughout the study (104 to 50 points vs 104 to 30 points).55 Median times to deterioration in FACT-P total score and PCS, as defined in Table 2, were delayed in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone arm relative to the placebo plus prednisone arm (Figure 1), as were times to deterioration on all other FACT-P subscales with the exception of social/family well-being.55 Additionally, median time to improvement in fatigue intensity (59 days vs 194 days; P=0.0155) was shortened in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone arm.53 Greater proportions of patients in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone arm than placebo plus prednisone arm reported improvements in FACT-P total and PCS scores (Table 3), as well as improvement on all FACT-P subscales (with the exception of social/family well-being; Figure 2). Similarly, a Brief Fatigue Inventory responder analysis of patients with clinically meaningful fatigue at baseline favored the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone arm (fatigue intensity, 58% vs 40%; P=0.0001; fatigue interference, 55% vs 38%; P=0.0075).53

Risk for a clinically meaningful deterioration in (a) FACT-P total score and (b) FACT-P PCS score. AA, abiraterone acetate; CI, confidence interval; ENZA, enzalutamide; FACT-P, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostate total score; NR, not reported; PBO, placebo; PCS, prostate cancer subscale; PRED, prednisone. *AFFIRM FACT-P PCS score data were taken from Cella D et al.63 and used with permission.

Proportion of patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer reporting a clinically meaningful improvement on the FACT-P subscale well-being scores after receipt of noncytotoxic therapies. AA, abiraterone acetate; ENZA, enzalutamide; FACT-P, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostate; PBO, placebo; PRED, prednisone. *P<0.0001 vs comparator.

Patients enrolled in COU-AA-301 were considered mildly symptomatic based on a median BPI-SF question 3 score of 3 (range 0–10, with higher scores indicating a greater severity of worst pain in the last 24 h).56 The BPI-SF pain data from COU-AA-301 showed a clear benefit in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone arm, as evidenced by longer median times to first deterioration in worst pain and pain interference, where progression on both pain outcomes was confirmed at two consecutive follow-up visits (Table 4). This study also measured palliation of worst pain, but only among those with clinically significant worst pain at baseline defined as a score of ⩾4 on BPI-SF question 3. Worst pain intensity palliation was defined as two consecutive follow-up visits (⩾4 weeks apart) at which the worst pain intensity score was ⩾30% lower than that at baseline without an increase in analgesic use, whereas pain interference palliation was defined as a decrease in mean pain interference score of ⩾1.25 points compared with baseline at two consecutive follow-up visits. Median time to palliation in worst pain intensity (5.6 vs 13.7 months; hazard ratio (HR), 1.68; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.20–2.34; P=0.0018) and interference (1.06 vs 3.7 months; HR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.31–2.74; P=0.0004) was shorter in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone arm than placebo plus prednisone arm. A greater proportion of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone than placebo plus prednisone recipients reported clinically meaningful palliation of worst pain intensity (45% vs 29%; P=0.0005) and pain interference (60% vs 38%; P=0.0002). Median duration of worst pain intensity palliation was also longer in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone arm than placebo plus prednisone arm (4.2 vs 2.1 months; P=0.0056).56

In COU-AA-302, baseline FACT-P total scores averaged ≈122, indicating a patient population with a better HRQoL than the COU-AA-301 population.57 Patients who received abiraterone acetate plus prednisone had lower risks for and longer median times to first deterioration in FACT-P total score and PCS scores than patients who received placebo plus prednisone (Figure 1). A significant difference was also seen in favor of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone regarding time to deterioration on each FACT-P subscale except social/family well-being.28 Median time to progression in pain interference with daily activities on the BPI-SF was longer in the abiraterone acetate plus prednisone arm than in the placebo plus prednisone arm, but no statistically significant between-group differences were observed regarding both mean and worst pain intensity (Table 4).28 Median time to opiate use for prostate cancer-related pain was delayed with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone relative to placebo plus prednisone (33.4 vs 23.4 months; HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.61–0.85).31

Enzalutamide

The FACT-P and BPI-SF completion rates were high throughout both registrational phase III studies of enzalutamide versus placebo, AFFIRM (following chemotherapy) and PREVAIL (chemotherapy-naive).24, 30, 52, 58

In AFFIRM, mean FACT-P total score decreased by 1.5 points with enzalutamide compared with 13.7 points with placebo after 25 weeks (P<0.001).35 In addition, significant treatment differences at week 25 favoring enzalutamide over placebo were evident for mean changes from baseline across all FACT-P subscale and index scores.35 Median times to deterioration in FACT-P total and PCS scores were longer in the enzalutamide arm than placebo arm (Figure 1).58 A greater proportion of patients in the enzalutamide arm than placebo arm experienced an improvement in FACT-P total and PCS scores (Table 3) and all FACT-P subscale scores (Figure 2).

In AFFIRM, enzalutamide was associated with change from baseline to week 13 improvements in mean scores of the FACT-P item 4 (that is, ‘I have pain’), BPI-SF pain severity and BPI-SF pain interference (all P<0.0001).58 Enzalutamide was associated with a 44% reduction in risk for pain progression relative to placebo on FACT-P item 4 in AFFIRM (Table 4).58 Of 64 patients (5%) who were evaluable for pain palliation assessments, 22 (45%) of 49 patients receiving enzalutamide reported pain palliation at week 13 versus one (7%) of 15 receiving placebo (difference 38%; P=0.0079). A smaller proportion of patients had BPI-SF pain progression in the enzalutamide arm than in the placebo arm (28% vs 39%; P=0.0018).58

The PREVAIL patient population had not yet been burdened by significant disease-related symptoms, but nevertheless had mild HRQoL impairment at baseline as evidenced by median baseline FACT-P total scores of 121 (range, 63–156) in the enzalutamide arm and 122 (range, 60–155) in the placebo arm.52 Multiple measures of HRQoL and health status favored enzalutamide over placebo, including changes from baseline in FACT-P total (−5.08 vs −10.87; P<0.0001), FACT-P PCS (−1.99 vs −3.18; P=0.0197) and EQ-5D visual analog scale (VAS; −5.18 vs −9.76; P<0.0010) scores measured at week 61.52 Median times to deterioration in FACT-P total and PCS scores were longer in the enzalutamide arm than placebo arm (Figure 1), as were median times to deterioration in all other FACT-P subscale scores.52 Similar findings in favor of enzalutamide over placebo were detected on the EQ-5D utility index (19.2 months vs 11.1 months; HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.52–0.73; P<0.0001) and EQ-5D VAS (22.1 months vs 13.8 months; HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.56–0.80; P<0.0001).52

The proportion of patients reporting improvements at any time during the study in FACT-P total (40% vs 23%) and PCS (55% vs 34%) scores (Table 3), as well as EQ-5D utility index (28% vs 16%) and VAS (27% vs 18%) scores, were higher in the enzalutamide than placebo arm (all P<0.0001).52 Significantly more enzalutamide patients than placebo patients had an improvement at any time during the study in all FACT-P subscale scores (Figure 2).

Mean change-from-baseline scores for BPI-SF severity (0.52 vs 0.79; P=0.0025) and interference (0.58 vs 0.99; P<0.0001) measured at week 25 favored enzalutamide over placebo.52 A lower proportion of enzalutamide patients than placebo patients reported progression of worst pain (29% vs 42%; P<0.0001) and average pain severity (28% vs 44%; P<0.0001) at week 13, but not week 25. Only the comparison on pain interference progression retained statistical significance in favor of enzalutamide at week 25 (23% vs 29%; P=0.0195).52 Median times to progression in BPI-SF worst pain, average pain severity, and pain interference were significantly longer in the enzalutamide arm than placebo arm (Table 4).52

Radium-223 dichloride

The ALSYMPCA trial compared the effects of radium-223 dichloride with placebo in mCRPC patients with symptomatic bone metastases who had either received docetaxel or were not planning to receive it.50 A unique aspect of this trial was that palliative external beam radiotherapy could be administered and patients could also take standard hormonal therapies, such as androgen receptor antagonists or ketoconazole. There was less deterioration in mean FACT-P total score from enrollment to week 16 in the radium-223 dichloride arm than the placebo arm (−2.7 vs −6.8; P=0.006). Clinically meaningful improvements in FACT-P total score also favored radium-223 dichloride over placebo (25% vs 16%; P=0.02; Table 3). In a smaller dose-finding study of 100 patients with painful bone metastases, 56% achieved pain palliation (using the pain index) at 8 weeks after receiving radium-223 dichloride at the approved dose of 50 kBq kg−1 monthly.47 For patients with pain response in the 50 kBq kg−1 dose group, BPI pain severity index decreased from 4.9 at baseline to 3.0 at week 8 (difference, 1.9; P=0.002).47

Sipuleucel-T

The IMPACT trial studied the role of the immunotherapy sip-T in the treatment of mCRPC patients with an expected survival of ⩾6 months.26 The original study design specified time to disease-related pain as a coprimary endpoint (along with objective disease progression), but this endpoint was eliminated at enrollment.46 Results were released summarizing time to development of disease-related pain (that is, pain post-enrollment) in a post hoc pooled analysis of three randomized phase III trials of sip-T in men with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic mCRPC with an expected survival of ⩾3 months.46 Time to disease-related pain was not significantly prolonged in the sip-T arm (Table 4) but time to opiate analgesic use was extended (12.6 months for patients in the sip-T arm vs 9.7 months in the control arm; HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.58–0.98; P=0.038).46 The HR for time to disease-related pain in the IMPACT study was 0.80 (95% CI, 0.56–1.15). 46

Cabazitaxel

The TROPIC trial examined the role of cabazitaxel in the treatment of mCRPC in the post-docetaxel setting, randomizing patients to either cabazitaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone.33 The pain response rate (7.7% vs 9.2%; P=0.63) and median time to pain progression (not reached vs 11.1 months; HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.69–1.19; P=0.52) using the McGill–Melzack present pain intensity instrument (Table 2) was similar in the mitoxantrone and cabazitaxel treatment groups, respectively. A more recent publication reported no meaningful differences seen in pain palliation between cabazitaxel and mitoxantrone.48

Docetaxel and estramustine

A phase II trial in Italy randomized 95 mCRPC patients to either docetaxel plus estramustine or docetaxel alone. There were no significant changes from baseline in EORTC QLQ-C30 total scores in either arm during treatment; however, only 59 of 95 patients completed both baseline and first post-treatment questionnaires at week 6, limiting the conclusions that can be drawn from this data set.49 At this time point, 15 of 59 patients (25%) receiving either docetaxel alone or with estramustine had an improvement in their pain as measured by EORTC QLQ-C30, and 20% had an improvement on the more detailed BPI.49

Nontaxane-based chemotherapy

A phase II study looked at the palliative benefit of nontaxane chemotherapy in patients who had progressed on docetaxel.51 Patients were randomized to receive either mitoxantrone, vinorelbine or etoposide. The primary endpoint was palliative benefit rate, defined as pain control without disease progression; HRQoL was a secondary endpoint and was measured with EORTC QLQ-C30 plus EORTC QLQ-PR25 (Table 2). In the mitoxantrone arm, palliative benefit rate was 36% vs 20% in the vinorelbine and etoposide arms, although no dedicated pain instrument was used. The authors reported that HRQoL responses were similar for the three groups and that fatigue had improved or stabilized in 24% and 25% of patients, respectively.51

Discussion

In the era of expanded therapeutic options, understanding how new treatments for mCRPC impact health states becomes increasingly important. Among the agents discussed in this review, abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, enzalutamide, and radium-223 dichloride offer clear HRQoL benefits and pain mitigation in addition to extended survival and improved cancer control.24, 25, 28, 29, 30, 31, 50 Conversely, the trials of mitoxantrone, docetaxel and cabazitaxel did not find statistically significant differences in HRQoL or pain versus comparison arms.33, 48, 49, 51 Sip-T appears to offer no palliative effect but may delay time to first opioid use.26, 46

We now have a far better basis for explaining to patients with mCRPC what they can expect as they initiate a new systemic therapy. For patients who have recently progressed to castration resistance and are either asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic, oral hormonal agents abiraterone acetate plus prednisone and enzalutamide offer a means to delay deterioration in HRQoL (FACT-P total score) by ≈4 months57 and 6 months,52 respectively, relative to their respective controls. The comparator-adjusted delay in mean pain intensity progression (BPI-SF) was 8 months with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone57 and the placebo-adjusted delay in deterioration of the FACT-P PCS pain-related score was 6 months with enzalutamide.52 Aside from delaying cancer-related symptoms associated with disease progression, these agents are associated with postponement of cytotoxic chemotherapy and its attendant toxicities. For men with symptomatic osseous metastatic disease, radium-223 dichloride offered HRQoL improvement and appeared to slow the subsequent decline in HRQoL when added to standard therapy.

Direct comparisons of the palliative effects and HRQoL impacts of the new agents for mCRPC treatment are not possible, as no head-to-head studies have been performed. One clinical issue that further complicates comparison of HRQoL data is the role of corticosteroids. Among agents currently used in mCRPC, corticosteroids are given routinely or required in conjunction with docetaxel, abiraterone acetate, cabazitaxel, and mitoxantrone, but are not required with enzalutamide or radium-223 dichloride. It is noteworthy that median time to mean pain intensity progression on the BPI-SF among chemotherapy-naive patients who received placebo plus prednisone in COU-AA-302 was 18.4 months, whereas in PREVAIL it was 5.5 months among patients who received placebo only. Other interstudy methodological factors, such as different methods by which a progression was defined and analyzed, likely explain such a large difference in this pain metric. Corticosteroids have known palliative effects but are associated with some risks that may impact HRQoL, including development of thrush, insomnia and fat deposition.59 The overall impact of corticosteroids remains poorly defined, especially as many corticosteroid-related toxicities are related to cumulative doses and duration of corticosteroid use increases as life-extending therapies are applied earlier in the treatment paradigm. Thus, careful consideration of the risk-benefit ratio of corticosteroids in mCRPC patients is appropriate; however, we found little exploration of independent effects of corticosteroids on HRQoL and pain palliation in the publications we reviewed.

Contextualizing HRQoL and pain palliation results is made difficult because of the inconsistency in methodology for evaluating these parameters. Most HRQoL instruments commonly used in mCRPC trials were not designed specifically for an mCRPC population. Consequently, these instruments may focus on issues more relevant to prostate cancer patients treated for localized disease and may not capture all major factors that drive HRQoL for men with metastatic disease. For example, Eton et al.60 used patient interviews to generate a list of 16 issues and outcomes that are most important to mCRPC patients, and included items such as PSA anxiety, urinary obstruction/frequency, and change in self-image, which are not well represented in FACT-P and EORTC QLQ-30 questionnaires. Lack of consistency in applying PRO instruments creates further variability. For example, COU-AA-301 and AFFIRM both used the FACT-P and BPI-SF instruments, but the study methods differ in areas such as frequency of PRO assessments and definition of outcomes. In COU-AA-301, patients were only considered eligible for improvement in HRQoL if their baseline FACT-P total score was ⩽122, whereas in AFFIRM, all patients were considered eligible for improvement in HRQoL regardless of baseline FACT-P score. In addition to establishing standard time points and ‘response’ or ‘progression’ benchmarks, reporting time-linked outcomes, such as time to pain palliation or duration of pain palliation, and analyzing symptomatic and asymptomatic patient populations separately are needed in order to produce more clinically relevant data.

Another difficulty in understanding the impact of therapies on disease burden and HRQoL in mCRPC comes from translating clinical trial data into real-world practice, as confounding issues relating to study design, patient selection, therapeutic implementation and healthcare delivery contribute to an efficacy-effectiveness gap. Patients enrolled in clinical trials may be healthier than average mCRPC patients, with fewer of the medical comorbidities often found in an older patient population. Patients with mCRPC in clinical trials may also have a lower burden of illness over the course of their disease. Sullivan et al.61 observed a cohort of 280 mCRPC patients for up to 9 months in the clinical practice setting and found that their deterioration in HRQoL was more rapid than that described in major clinical trials, suggesting that clinical trial data may underestimate HRQoL challenges faced by real-world mCRPC patient populations. This also implies that the quality and depth of HRQoL data collected in a trial depends heavily on the approach used to gather it. More prospective observational data with serial HRQoL assessments is required to elucidate disparities between clinical trial and real-world settings regarding patient well-being. Although HRQoL instruments can be incorporated into practice,62 the manner in which HRQoL data from clinical trials are presented must be better standardized and reported in a way that lends itself to incorporation into everyday practice.

Validating the implementation of PRO questionnaires in the clinical practice setting is required to ensure that information is captured accurately and without bias. Yet systematic collection of PRO data in routine clinical practice requires time and effort, placing a burden on patients, families, and clinical staff. In addition, although HRQoL instruments such as FACT-P and EORTC QLQ-C30 are validated for use in research, their utility in general clinical practice is unclear. Ultimately, once a practice completes PROs, clinicians will need tools to view sequential HRQoL information in parallel with the rest of the medical record so that these data can be interpreted in the context of the patient’s treatment plan and cancer control. Applications that help clinicians explain to patients the impact of therapy on HRQoL, ideally with graphical depiction, will be helpful in stimulating dialog about the overall value of treatment.

Conclusion

Since 2010, mCRPC has seen an increasing number of therapeutic options. When considering a specific treatment decision, a clinician must balance the potential HRQoL improvement that could result from disease control with potential HRQoL decrements related to adverse effects associated with treatment. To give context to the relative impact of treatments on HRQoL and pain, it is critical to understand the underlying disease burden in mCRPC patients and to standardize methods for measuring and quantifying HRQoL and symptom assessments. Active treatment with noncytotoxic agents, abiraterone acetate plus prednisone and enzalutamide, and radium-223 dichloride and sip-T, is associated with varying levels of improvement in HRQoL and pain status, but direct comparisons between treatments are not possible. As patients progress to mCRPC and receive life-extending therapies, PROs that are subject to validation processes in the clinical practice setting will be required to monitor their experiences with the disease and its treatment.

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A . Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2015; 65: 5–29.

Amling CL, Bergstralh EJ, Blute ML, Slezak JM, Zincke H . Defining prostate specific antigen progression after radical prostatectomy: what is the most appropriate cut point? J Urol 2001; 165: 1146–1151.

Khuntia D, Reddy CA, Mahadevan A, Klein EA, Kupelian PA . Recurrence-free survival rates after external-beam radiotherapy for patients with clinical T1-T3 prostate carcinoma in the prostate-specific antigen era: what should we expect? Cancer 2004; 100: 1283–1292.

Kuban DA, Thames HD, Levy LB, Horwitz EM, Kupelian PA, Martinez AA et al. Long-term multi-institutional analysis of stage T1-T2 prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy in the PSA era. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003; 57: 915–928.

Kupelian PA, Thakkar VV, Khuntia D, Reddy CA, Klein EA, Mahadevan A . Hypofractionated intensity-modulated radiotherapy (70 Gy at 2.5 Gy per fraction) for localized prostate cancer: long-term outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005; 63: 1463–1468.

Beyer DC . Brachytherapy for recurrent prostate cancer after radiation therapy. Semin Radiat Oncol 2003; 13: 158–165.

Han M, Partin AW, Zahurak M, Piantadosi S, Epstein JI, Walsh PC . Biochemical (prostate specific antigen) recurrence probability following radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer. J Urol 2003; 169: 517–523.

Simmons MN, Stephenson AJ, Klein EA . Natural history of biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy: risk assessment for secondary therapy. Eur Urol 2007; 51: 1175–1184.

Rosenbaum E, Partin A, Eisenberger MA . Biochemical relapse after primary treatment for prostate cancer: studies on natural history and therapeutic considerations. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2004; 2: 249–256.

Kirby M, Hirst C, Crawford ED . Characterising the castration resistant prostate cancer population: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract 2011; 65: 1180–1192.

Crawford ED, Eisenberger MA, McLeod DG, Spaulding JT, Benson R, Dorr FA et al. A controlled trial of leuprolide with and without flutamide in prostatic carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1989; 321: 419–424.

Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, Horti J, Pluzanska A, Chi KN et al.; TAX 327 Investigators. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1502–1512.

Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MH, Lara PN Jr, Jones JA, Taplin ME et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1513–1520.

Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, Tchekmedyian S, Venner P, Lacombe L et al.; Zoledronic Acid Prostate Cancer Study Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of zoledronic acid in patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94: 1458–1468.

Sternberg CN, Petrylak DP, Sartor O, Witjes JA, Demkow T, Ferrero JM et al. Multinational, double-blind, phase III study of prednisone and either satraplatin or placebo in patients with castrate-refractory prostate cancer progressing after prior chemotherapy: the SPARC trial. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 5431–5438.

Scher HI, Halabi S, Tannock I, Morris M, Sternberg CN, Carducci MA et al.; Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group. Design and end points of clinical trials for patients with progressive prostate cancer and castrate levels of testosterone: recommendations of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 1148–1159.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2015).

Calvert M, Blazeby J, Altman DG, Revicki DA, Moher D, Brundage MD, ; CONSORT PRO Group. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: the CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA 2013; 309: 814–822.

Tannock IF, Osoba D, Stockler MR, Ernst DS, Neville AJ, Moore MJ et al. Chemotherapy with mitoxantrone plus prednisone or prednisone alone for symptomatic hormone-resistant prostate cancer: a Canadian randomized trial with palliative end points. J Clin Oncol 1996; 14: 1756–1764.

Porter AT, McEwan AJ, Powe JE, Reid R, McGowan DG, Lukka H et al. Results of a randomized phase-III trial to evaluate the efficacy of strontium-89 adjuvant to local field external beam irradiation in the management of endocrine resistant metastatic prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1993; 25: 805–813.

Serafini AN, Houston SJ, Resche I, Quick DP, Grund FM, Ell PJ et al. Palliation of pain associated with metastatic bone cancer using samarium-153 lexidronam: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 1574–1581.

Berry DL, Moinpour CM, Jiang CS, Ankerst DP, Petrylak DP, Vinson LV et al. Quality of life and pain in advanced stage prostate cancer: results of a Southwest Oncology Group randomized trial comparing docetaxel and estramustine to mitoxantrone and prednisone. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 2828–2835.

Colloca G, Venturino A, Checcaglini F . Patient-reported outcomes after cytotoxic chemotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev 2010; 36: 501–506.

Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf DE, Loriot Y, Sternberg CN, Higano CS et al.; PREVAIL Investigators. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 424–433.

Fizazi K, Scher HI, Molina A, Logothetis CJ, Chi KN, Jones RJ et al.; COU-AA-301 Investigators. Abiraterone acetate for treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: final overall survival analysis of the COU-AA-301 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: 983–992.

Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF et al.; IMPACT Study Investigators. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 411–422.

Sartor O, Coleman R, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, Helle SI, O'Sullivan JM et al. Effect of radium-223 dichloride on symptomatic skeletal events in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases: results from a phase 3, double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 738–746.

Rathkopf DE, Smith MR, de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Shore ND, de Souza P et al. Updated interim efficacy analysis and long-term safety of abiraterone acetate in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients without prior chemotherapy (COU-AA-302). Eur Urol 2014; 66: 815–825.

Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, Molina A, Logothetis CJ, de Souza P et al.; COU-AA-302 Investigators. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 138–148.

Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, Taplin ME, Sternberg CN, Miller K et al.; AFFIRM Investigators. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 1187–1197.

Ryan CJ, Smith MR, Fizazi K, Saad F, Mulders PF, Sternberg CN et al.; COU-AA-302 Investigators. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus placebo plus prednisone in chemotherapy-naive men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (COU-AA-302): final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 152–160.

Hoskin P, Sartor O, O'Sullivan JM, Johannessen DC, Helle SI, Logue J et al. Efficacy and safety of radium-223 dichloride in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and symptomatic bone metastases, with or without previous docetaxel use: a prespecified subgroup analysis from the randomised, double-blind, phase 3 ALSYMPCA trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 1397–1406.

de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, Hansen S, Machiels JP, Kocak I et al.; TROPIC Investigators. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet 2010; 376: 1147–1154.

Basch E, Abernethy AP, Mullins CD, Reeve BB, Smith ML, Coons SJ et al. Recommendations for incorporating patient-reported outcomes into clinical comparative effectiveness research in adult oncology. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 4249–4255.

Cella D, Ivanescu C, Holmstrom S, Bui CN, Spalding J, Fizazi K . Impact of enzalutamide on quality of life in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer after chemotherapy: additional analyses from the AFFIRM randomized clinical trial. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 179–185.

Kelly WK, Halabi S, Carducci M, George D, Mahoney JF, Stadler WM et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial comparing docetaxel and prednisone with or without bevacizumab in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: CALGB 90401. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 1534–1540.

Meulenbeld HJ, van Werkhoven ED, Coenen JL, Creemers GJ, Loosveld OJ, de Jong PC et al. Randomised phase II/III study of docetaxel with or without risedronate in patients with metastatic Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer (CRPC), the Netherlands Prostate Study (NePro). Eur J Cancer 2012; 48: 2993–3000.

Dawson N, Payne H, Battersby C, Taboada M, James N . Health-related quality of life in pain-free or mildly symptomatic patients with metastatic hormone-resistant prostate cancer following treatment with the specific endothelin A receptor antagonist zibotentan (ZD4054). J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2011; 137: 99–113.

Quinn DI, Tangen CM, Hussain M, Lara PN Jr, Goldkorn A, Moinpour CM et al. Docetaxel and atrasentan versus docetaxel and placebo for men with advanced castration-resistant prostate cancer (SWOG S0421): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 893–900.

Fizazi K, Higano CS, Nelson JB, Gleave M, Miller K, Morris T et al. Phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled study of docetaxel in combination with zibotentan in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 1740–1747.

Basch E, Autio KA, Smith MR, Bennett AV, Weitzman AL, Scheffold C et al. Effects of cabozantinib on pain and narcotic use in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer: results from a phase 2 nonrandomized expansion cohort. Eur Urol 2015; 67: 310–318.

Cella D, Nichol MB, Eton D, Nelson JB, Mulani P . Estimating clinically meaningful changes for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostate: results from a clinical trial of patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Value Health 2009; 12: 124–129.

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009; 45: 228–247.

Esper P, Mo F, Chodak G, Sinner M, Cella D, Pienta KJ . Measuring quality of life in men with prostate cancer using the functional assessment of cancer therapy-prostate instrument. Urology 1997; 50: 920–928.

Cleeland C . The Brief Pain Inventory: User Guide. Available at http://www.mdanderson.org/education-and-research/departments-programs-and-labs/departments-and-divisions/symptom-research/symptom-assessment-tools/BPI_UserGuide.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2015).

Small EJ, Higano CS, Kantoff PW, Whitmore JB, Frohlich MW, Petrylak DP . Time to disease-related pain and first opioid use in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with sipuleucel-T. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2014; 17: 259–264.

Nilsson S, Strang P, Aksnes AK, Franzèn L, Olivier P, Pecking A et al. A randomized, dose-response, multicenter phase II study of radium-223 chloride for the palliation of painful bone metastases in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer 2012; 48: 678–686.

Bahl A, Oudard S, Tombal B, Ozgüroglu M, Hansen S, Kocak I et al.; TROPIC Investigators. Impact of cabazitaxel on 2-year survival and palliation of tumour-related pain in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated in the TROPIC trial. Ann Oncol 2013; 24: 2402–2408.

Caffo O, Sava T, Comploj E, Fariello A, Zustovich F, Segati R et al. Impact of docetaxel-based chemotherapy on quality of life of patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer: results from a prospective phase II randomized trial. BJU Int 2011; 108: 1825–1832.

Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, Helle SI, O'Sullivan JM, Fosså SD et al.; ALSYMPCA Investigators. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 213–223.

Joly F, Delva R, Mourey L, Sevin E, Bompas E, Vedrine L et al. Clinical benefits of non-taxane chemotherapies in unselected symptomatic metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients after docetaxel: the Getug P02 study. BJU Int 2015; 115: 65–73.

Loriot Y, Miller K, Sternberg CN, Fizazi K, De Bono JS, Chowdhury S et al. Effect of enzalutamide on health-related quality of life, pain, and skeletal-related events in asymptomatic and minimally symptomatic, chemotherapy-naive patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (PREVAIL): results from a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 509–521.

Sternberg CN, Molina A, North S, Mainwaring P, Fizazi K, Hao Y et al. Effect of abiraterone acetate on fatigue in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer after docetaxel chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2013; 24: 1017–1025.

de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, Fizazi K, North S, Chu L et al.; COU-AA-301 Investigators. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 1995–2005.

Harland S, Staffurth J, Molina A, Hao Y, Gagnon DD, Sternberg CN et al.; COU-AA-301 Investigators. Effect of abiraterone acetate treatment on the quality of life of patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer after failure of docetaxel chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer 2013; 49: 3648–3657.

Logothetis CJ, Basch E, Molina A, Fizazi K, North SA, Chi KN et al. Effect of abiraterone acetate and prednisone compared with placebo and prednisone on pain control and skeletal-related events in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: exploratory analysis of data from the COU-AA-301 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: 1210–1217.

Basch E, Autio K, Ryan CJ, Mulders P, Shore N, Kheoh T et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus prednisone alone in chemotherapy-naive men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: patient-reported outcome results of a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 1193–1199.

Fizazi K, Scher HI, Miller K, Basch E, Sternberg CN, Cella D et al. Effect of enzalutamide on time to first skeletal-related event, pain, and quality of life in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: results from the randomised, phase 3 AFFIRM trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 1147–1156.

Dorff TB, Crawford ED . Management and challenges of corticosteroid therapy in men with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Ann Oncol 2013; 24: 31–38.

Eton DT, Shevrin DH, Beaumont J, Victorson D, Cella D . Constructing a conceptual framework of patient-reported outcomes for metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Value Health 2010; 13: 613–623.

Sullivan PW, Mulani PM, Fishman M, Sleep D . Quality of life findings from a multicenter, multinational, observational study of patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Qual Life Res 2007; 16: 571–575.

Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Schornagel JH, Wever LD, Aaronson NK . Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 288: 3027–3034.

Cella D, Ivanescu C, Phung D, Mansbach H, Holmstrom S, Naidoo S Impact on quality of life of enzalutamide or abiraterone acetate+prednisone in the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer that has progressed on or after doxetaxel—a comparative effectiveness study. Presented at International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research 20th Annual International Meeting, 16–20 May 2015, Philadelphia, PA, USA 2015.

World Health Organization. Palliative care: symptom management and end-of-life care. Available at http://www.who.int/3by5/publications/documents/en/genericpalliativecare082004.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2015).

Ringash J, O’Sullivan B, Bezjak A, Redelmeier DA . Interpreting clinically significant changes in patient-reported outcomes. Cancer 2007; 110: 196–202.

Yost KJ, Eton DT . Combining distribution- and anchor-based approaches to determine minimally important differences: the FACIT experience. Eval Health Prof 2005; 28: 172–191.

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ et al. The European Organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993; 85: 365–376.

Groenvold M, Klee MC, Sprangers MA, Aaronson NK . Validation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 quality of life questionnaire through combined qualitative and quantitative assessment of patient-observer agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 1997; 50: 441–450.

Hjermstad MJ, Fossa SD, Bjordal K, Kaasa S . Test/retest study of the European Organization for research and treatment of cancer core quality-of-life questionnaire. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13: 1249–1254.

Osoba D, Tannock IF, Ernst S, Neville AJ . Health-related quality of life in men with metastatic prostate cancer treated with prednisone alone or mitoxantrone and prednisone. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 1654–1663.

Borghede G, Sullivan M . Measurement of quality of life in localized prostatic cancer patients treated with radiotherapy. Development of a prostate cancer-specific module supplementing the EORTC QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res 1996; 5: 212–222.

Maringwa J, Quinten C, King M, Ringash J, Osoba D, Coens C et al.; EORTC PROBE Project and Brain Cancer Group. Minimal clinically meaningful differences for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-BN20 scales in brain cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2011; 22: 2107–2112.

The EuroQol group. EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health related quality of life. Health Policy 1990; 16: 199–208.

Rabin R, de Charro F . EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med 2001; 33: 337–343.

Brazier J, Jones N, Kind P . Testing the validity of the Euroqol and comparing it with the SF-36 health survey questionnaire. Qual Life Res 1993; 2: 169–180.

Pickard AS, Neary MP, Cella D . Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007; 5: 70.

Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, Morrissey M, Johnson BA, Wendt JK et al. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer 1999; 85: 1186–1196.

Farrar JT, Rk Portenoy, Berlin JA, Kinman JL, Strom BL . Defining the clinically important difference in pain outcome measures. Pain 2000; 88: 287–294.

Melzack R . The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain 1975; 1: 277–299.

Melzack R . The McGill Pain Questionnaire: from description to measurement. Anesthesiology 2005; 103: 199–202.

Serlin RC, Mendoza TR, Nakamura Y, Edwards KR, Cleeland CS . When is cancer pain mild, moderate or severe? Grading pain severity by its interference with function. Pain 1995; 61: 277–284.

Berthold DR, Pond GR, Roessner M, de Wit R, Eisenberger M, Tannock AI, ; TAX-327 investigators. Treatment of hormone-refractory prostate cancer with docetaxel or mitoxantrone: relationships between prostate-specific antigen, pain and quality of life response and survival in the TAX-327 Study. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 2763–2767.

Petrioli R, Fiaschi AI, Pozzessere D, Messinese S, Sabatino M, Marsili S et al. Weekly epirubicin in patients with hormone-resistant prostate cancer. Br J Cancer 2002; 87: 720–725.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc., and Medivation Inc. Medical writing and editorial support funded by Astellas and Medivation were provided by Malcolm Darkes, PhD, and Shannon Davis of Infusion Communications, based on detailed discussion and feedback from all authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

DJG has received research support from Astellas, Exelixis, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Cougar Biotechnology (now Janssen Oncology), Millennium, Novartis, Pfizer, Viamet, and Progenics, consultancy fees from Astellas, Aveo, Bayer, Dendreon, Exelixis, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Medivation, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Teva, Viamet, and Progenics, and honoraria from Dendreon and Sanofi. CMD is a paid consultant for Genentech, Iconic Therapeutics, Medivation, and Relypsa. NO was an employee of Medivation when the article was developed and owns stock in Medivation. SF is an employee of Astellas and holds stock in Johnson & Johnson. TBD has received research support from BMS, and has served as a consultant for Dendreon, Janssen, and Medivation, and has received honoraria from Astellas, Bayer, Pfizer, and Sanofi. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Nussbaum, N., George, D., Abernethy, A. et al. Patient experience in the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: state of the science. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 19, 111–121 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/pcan.2015.42

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pcan.2015.42

This article is cited by

-

Health-related quality of life, psychological distress, and fatigue in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients treated with radium-223 therapy

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2023)

-

Impact of enzalutamide on patient-reported fatigue in patients with prostate cancer: data from the pivotal clinical trials

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2022)

-

US Population Reference Values for Health-Related Quality of Life Questionnaires Based on Demographics of Patients with Prostate Cancer

Advances in Therapy (2022)

-

Pharmacological and genetic targeting of 5-lipoxygenase interrupts c-Myc oncogenic signaling and kills enzalutamide-resistant prostate cancer cells via apoptosis

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Understanding symptomatic experience, impact, and emotional response in recently diagnosed metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a qualitative study

Supportive Care in Cancer (2020)