Abstract

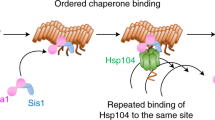

Protein misfolding underlies many neurodegenerative diseases, including the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (prion diseases). Although cells typically recognize and process misfolded proteins, prion proteins evade protective measures by forming stable, self-replicating aggregates. However, coexpression of dominant-negative prion mutants can overcome aggregate accumulation and disease progression through currently unknown pathways. Here we determine the mechanisms by which two mutants of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sup35 protein cure the [PSI+] prion. We show that both mutants incorporate into wild-type aggregates and alter their physical properties in different ways, diminishing either their assembly rate or their thermodynamic stability. Whereas wild-type aggregates are recalcitrant to cellular intervention, mixed aggregates are disassembled by the molecular chaperone Hsp104. Thus, rather than simply blocking misfolding, dominant-negative prion mutants target multiple events in aggregate biogenesis to enhance their susceptibility to endogenous quality-control pathways.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$189.00 per year

only $15.75 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Tuite, M.F. & Serio, T.R. The prion hypothesis: from biological anomaly to basic regulatory mechanism. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 823–833 (2010).

Masel, J., Jansen, V.A. & Nowak, M.A. Quantifying the kinetic parameters of prion replication. Biophys. Chem. 77, 139–152 (1999).

Collinge, J. et al. Kuru in the 21st century—an acquired human prion disease with very long incubation periods. Lancet 367, 2068–2074 (2006).

Gambetti, P., Parchi, P., Petersen, R.B., Chen, S.G. & Lugaresi, E. Fatal familial insomnia and familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: clinical, pathological and molecular features. Brain Pathol. 5, 43–51 (1995).

Webb, T.E. et al. Phenotypic heterogeneity and genetic modification of P102L inherited prion disease in an international series. Brain 131, 2632–2646 (2008).

Deslys, J.P. et al. Genotype at codon 129 and susceptibility to Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Lancet 351, 1251 (1998).

Cervenakova, L. et al. Phenotype-genotype studies in kuru: implications for new variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 13239–13241 (1998).

Huillard d'Aignaux, J. et al. Incubation period of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in human growth hormone recipients in France. Neurology 53, 1197–1201 (1999).

Baker, H.E. et al. Amino acid polymorphism in human prion protein and age at death in inherited prion disease. Lancet 337, 1286 (1991).

Dickinson, A.G., Meikle, V.M. & Fraser, H. Identification of a gene which controls the incubation period of some strains of scrapie agent in mice. J. Comp. Pathol. 78, 293–299 (1968).

Carlson, G.A. et al. Genetics and polymorphism of the mouse prion gene complex: control of scrapie incubation time. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 5528–5540 (1988).

Shibuya, S., Higuchi, J., Shin, R.W., Tateishi, J. & Kitamoto, T. Codon 219 Lys allele of PRNP is not found in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Ann. Neurol. 43, 826–828 (1998).

Goldmann, W., Hunter, N., Smith, G., Foster, J. & Hope, J. PrP genotype and agent effects in scrapie: change in allelic interaction with different isolates of agent in sheep, a natural host of scrapie. J. Gen. Virol. 75, 989–995 (1994).

Westaway, D. et al. Homozygosity for prion protein alleles encoding glutamine-171 renders sheep susceptible to natural scrapie. Genes Dev. 8, 959–969 (1994).

Belt, P.B. et al. Identification of five allelic variants of the sheep PrP gene and their association with natural scrapie. J. Gen. Virol. 76, 509–517 (1995).

Clouscard, C. et al. Different allelic effects of the codons 136 and 171 of the prion protein gene in sheep with natural scrapie. J. Gen. Virol. 76, 2097–2101 (1995).

Ikeda, T. et al. Amino acid polymorphisms of PrP with reference to onset of scrapie in Suffolk and Corriedale sheep in Japan. J. Gen. Virol. 76, 2577–2581 (1995).

Bossers, A., Schreuder, B.E., Muileman, I.H., Belt, P.B. & Smits, M.A. PrP genotype contributes to determining survival times of sheep with natural scrapie. J. Gen. Virol. 77, 2669–2673 (1996).

Hunter, N., Moore, L., Hosie, B.D., Dingwall, W.S. & Greig, A. Association between natural scrapie and PrP genotype in a flock of Suffolk sheep in Scotland. Vet. Rec. 140, 59–63 (1997).

O'Rourke, K.I. et al. PrP genotypes and experimental scrapie in orally inoculated Suffolk sheep in the United States. J. Gen. Virol. 78, 975–978 (1997).

Baylis, M. et al. Scrapie epidemic in a fully PrP-genotyped sheep flock. J. Gen. Virol. 83, 2907–2914 (2002).

Kaneko, K. et al. Evidence for protein X binding to a discontinuous epitope on the cellular prion protein during scrapie prion propagation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 10069–10074 (1997).

Perrier, V. et al. Dominant-negative inhibition of prion replication in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13079–13084 (2002).

Crozet, C. et al. Inhibition of PrPSc formation by lentiviral gene transfer of PrP containing dominant negative mutants. J. Cell Sci. 117, 5591–5597 (2004).

Furuya, K. et al. Intracerebroventricular delivery of dominant negative prion protein in a mouse model of iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease after dura graft transplantation. Neurosci. Lett. 402, 222–226 (2006).

Toupet, K. et al. Effective gene therapy in a mouse model of prion diseases. PLoS ONE 3, e2773 (2008).

Geoghegan, J.C., Miller, M.B., Kwak, A.H., Harris, B.T. & Supattapone, S. Trans-dominant inhibition of prion propagation in vitro is not mediated by an accessory cofactor. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000535 (2009).

Atarashi, R., Sim, V.L., Nishida, N., Caughey, B. & Katamine, S. Prion strain-dependent differences in conversion of mutant prion proteins in cell culture. J. Virol. 80, 7854–7862 (2006).

Lee, C.I., Yang, Q., Perrier, V. & Baskakov, I.V. The dominant-negative effect of the Q218K variant of the prion protein does not require protein X. Protein Sci. 16, 2166–2173 (2007).

Masel, J. & Jansen, V.A. Designing drugs to stop the formation of prion aggregates and other amyloids. Biophys. Chem. 88, 47–59 (2000).

Satpute-Krishnan, P. & Serio, T.R. Prion protein remodelling confers an immediate phenotypic switch. Nature 437, 262–265 (2005).

Satpute-Krishnan, P., Langseth, S.X. & Serio, T.R. Hsp104-dependent remodeling of prion complexes mediates protein-only inheritance. PLoS Biol. 5, e24 (2007).

Ness, F., Ferreira, P., Cox, B.S. & Tuite, M.F. Guanidine hydrochloride inhibits the generation of prion “seeds” but not prion protein aggregation in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 5593–5605 (2002).

Kawai-Noma, S., Pack, C.G., Tsuji, T., Kinjo, M. & Taguchi, H. Single mother-daughter pair analysis to clarify the diffusion properties of yeast prion Sup35 in guanidine-HCl-treated [PSI] cells. Genes Cells 14, 1045–1054 (2009).

Chernoff, Y.O., Lindquist, S.L., Ono, B., Inge-Vechtomov, S.G. & Liebman, S.W. Role of the chaperone protein Hsp104 in propagation of the yeast prion-like factor [PSI+]. Science 268, 880–884 (1995).

Tipton, K.A., Verges, K.J. & Weissman, J.S. In vivo monitoring of the prion replication cycle reveals a critical role for Sis1 in delivering substrates to Hsp104. Mol. Cell 32, 584–591 (2008).

Higurashi, T., Hines, J.K., Sahi, C., Aron, R. & Craig, E.A. Specificity of the J-protein Sis1 in the propagation of 3 yeast prions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 16596–16601 (2008).

Tessarz, P., Mogk, A. & Bukau, B. Substrate threading through the central pore of the Hsp104 chaperone as a common mechanism for protein disaggregation and prion propagation. Mol. Microbiol. 68, 87–97 (2008).

DePace, A.H., Santoso, A., Hillner, P. & Weissman, J.S. A critical role for amino-terminal glutamine/asparagine repeats in the formation and propagation of a yeast prion. Cell 93, 1241–1252 (1998).

Doel, S.M., McCready, S.J., Nierras, C.R. & Cox, B.S. The dominant PNM2-mutation which eliminates the psi factor of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is the result of a missense mutation in the gene. Genetics 137, 659–670 (1994).

Young, C.S.H. & Cox, B.S. Extrachromosomal elements in a super-suppression system of yeast. I. A nuclear gene controlling the inheritance of the extrachromosomal elements. Heredity 26, 413–422 (1971).

Derkatch, I.L., Bradley, M.E., Zhou, P. & Liebman, S.W. The PNM2 mutation in the prion protein domain of SUP35 has distinct effects on different variants of the [PSI+] prion in yeast. Curr. Genet. 35, 59–67 (1999).

Kochneva-Pervukhova, N.V. et al. Mechanism of inhibition of [PSI+] prion determinant propagation by a mutation of the N-terminus of the yeast Sup35 protein. EMBO J. 17, 5805–5810 (1998).

Osherovich, L.Z., Cox, B.S., Tuite, M.F. & Weissman, J.S. Dissection and design of yeast prions. PLoS Biol. 2, E86 (2004).

Tanaka, M., Collins, S.R., Toyama, B.H. & Weissman, J.S. The physical basis of how prion conformations determine strain phenotypes. Nature 442, 585–589 (2006).

Derdowski, A., Sindi, S.S., Klaips, C.L., DiSalvo, S. & Serio, T.R. A size threshold limits prion transmission and establishes phenotypic diversity. Science 330, 680–683 (2010).

Kryndushkin, D.S., Alexandrov, I.M., Ter-Avanesyan, M.D. & Kushnirov, V.V. Yeast [PSI+] prion aggregates are formed by small Sup35 polymers fragmented by Hsp104. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 49636–49643 (2003).

Cox, B., Ness, F. & Tuite, M. Analysis of the generation and segregation of propagons: entities that propagate the [PSI+] prion in yeast. Genetics 165, 23–33 (2003).

Tessier, P.M. & Lindquist, S. Prion recognition elements govern nucleation, strain specificity and species barriers. Nature 447, 556–561 (2007).

Krishnan, R. & Lindquist, S.L. Structural insights into a yeast prion illuminate nucleation and strain diversity. Nature 435, 765–772 (2005).

Toyama, B.H., Kelly, M.J., Gross, J.D. & Weissman, J.S. The structural basis of yeast prion strain variants. Nature 449, 233–237 (2007).

Santoso, A., Chien, P., Osherovich, L.Z. & Weissman, J.S. Molecular basis of a yeast prion species barrier. Cell 100, 277–288 (2000).

Moosavi, B., Wongwigkarn, J. & Tuite, M.F. Hsp70/Hsp90 co-chaperones are required for efficient Hsp104-mediated elimination of the yeast [PSI+] prion but not for prion propagation. Yeast 27, 167–179 (2010).

Reidy, M. & Masison, D.C. Sti1 regulation of Hsp70 and Hsp90 is critical for curing of Saccharomyces cerevisiae [PSI+] prions by Hsp104. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 3542–3552 (2010).

Bossers, A. et al. Scrapie susceptibility-linked polymorphisms modulate the in vitro conversion of sheep prion protein to protease-resistant forms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 4931–4936 (1997).

Hizume, M. et al. Human prion protein (PrP) 219K is converted to PrPSc but shows heterozygous inhibition in variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease infection. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 3603–3609 (2009).

Safar, J. et al. Eight prion strains have PrP(Sc) molecules with different conformations. Nat. Med. 4, 1157–1165 (1998).

Belli, G., Gari, E., Aldea, M. & Herrero, E. Functional analysis of yeast essential genes using a promoter-substitution cassette and the tetracycline-regulatable dual expression system. Yeast 14, 1127–1138 (1998).

Pezza, J.A. et al. The NatA acetyltransferase couples Sup35 prion complexes to the [PSI+] phenotype. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1068–1080 (2009).

Bagriantsev, S.N., Gracheva, E.O., Richmond, J.E. & Liebman, S.W. Variant-specific [PSI+] infection is transmitted by Sup35 polymers within [PSI+] aggregates with heterogeneous protein composition. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 2433–2443 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Bender, J. Laney, B. Cox, M. Tuite and members of the Serio, Laney and Tuite labs for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript, and S. Lindquist (Whitehead Institute), D. Stillman (The University of Utah), M. Tuite (University of Kent), E. Craig (University of Wisconsin–Madison), J. Weissman (University of California, San Francisco) and J. Laney (Brown University) for reagents. We also thank C. Klaips and B. Rock for technical assistance. This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AG032818 to S.D., GM085976 to A.D., GM080907 to J.A.P. and GM069802 to T.R.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D. and T.R.S. designed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. S.D., A.D. and J.A.P. performed the experiments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–6 and Supplementary Tables 1–3 (PDF 5622 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

DiSalvo, S., Derdowski, A., Pezza, J. et al. Dominant prion mutants induce curing through pathways that promote chaperone-mediated disaggregation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18, 486–492 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2031

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2031

This article is cited by

-

Nucleation seed size determines amyloid clearance and establishes a barrier to prion appearance in yeast

Nature Structural & Molecular Biology (2020)

-

A naturally occurring variant of the human prion protein completely prevents prion disease

Nature (2015)

-

Loss of amino-terminal acetylation suppresses a prion phenotype by modulating global protein folding

Nature Communications (2014)

-

Amyloid-associated activity contributes to the severity and toxicity of a prion phenotype

Nature Communications (2014)