Abstract

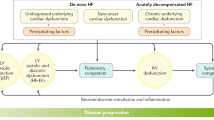

Heart failure is a global public health problem that affects more than 26 million people worldwide. The global burden of heart failure is growing and is expected to increase substantially with the ageing of the population. Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction accounts for approximately 50% of all cases of heart failure in the United States and is associated with substantial morbidity and reduced quality of life. Several diseases, such as myocardial infarction, certain infectious diseases and endocrine disorders, can initiate a primary pathophysiological process that can lead to reduced ventricular function and to heart failure. Initially, ventricular impairment is compensated for by the activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, but chronic activation of these pathways leads to worsening cardiac function. The symptoms of heart failure can be associated with other conditions and include dyspnoea, fatigue, limitations in exercise tolerance and fluid accumulation, which can make diagnosis difficult. Management strategies include the use of pharmacological therapies and implantable devices to regulate cardiac function. Despite these available treatments, heart failure remains incurable, and patients have a poor prognosis and high mortality rate. Consequently, the development of new therapies is imperative and requires further research.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 1 digital issues and online access to articles

$99.00 per year

only $99.00 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mann, D. L. in Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine (eds Bonow, R. O., Mann, D. L., Zipes, D. P. & Libby, P. ) 487–504 (Elsevier Saunders, 2012).

Yancy, C. W. et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62, e147–e239 (2013). A guideline statement from the ACCF and AHA addressing diagnostic and treatment considerations in patients with acute and chronic heart failure.

Lang, R. M. et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 28, 1–39.e14 (2015).

Benjamin, E. J. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics — 2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 135, e146–e603 (2017).

Dickstein, K. et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). Eur. Heart J. 29, 2388–2442 (2008). A guideline statement from the European Society of Cardiology addressing diagnostic and treatment considerations in patients with acute and chronic heart failure.

Weiwei, C. et al. Outline of the report on cardiovascular diseases in China, 2014. Eur. Hear. J. Suppl. 18, F2–F11 (2016).

Huffman, M. D. & Prabhakaran, D. Heart failure: epidemiology and prevention in India. Natl Med. J. India 23, 283–288 (2010).

Okamoto, H. & Kitabatake, A. The epidemiology of heart failure in Japan [Japanese]. Nihon Rinsho 61, 709–714 (2003).

Shiba, N. et al. Trend of westernization of etiology and clinical characteristics of heart failure patients in Japan — first report from the CHART-2 study. Circ. J. 75, 823–833 (2011).

Damasceno, A. et al. The causes, treatment, and outcome of acute heart failure in 1006 Africans from 9 countries. Arch. Intern. Med. 172, 1386–1394 (2012).

Dokainish, H. et al. Global mortality variations in patients with heart failure: results from the International Congestive Heart Failure (INTER-CHF) prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob. Health 5, e665–e672 (2017).

Levy, D. et al. Long-term trends in the incidence of and survival with heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 1397–1402 (2002).

Roger, V. L. et al. Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. JAMA 292, 344–350 (2004).

Barker, W. H., Mullooly, J. P. & Getchell, W. Changing incidence and survival for heart failure in a well-defined older population, 1970–1974 and 1990–1994. Circulation 113, 799–805 (2006).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Lifetime risk for developing congestive heart failure: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 106, 3068–3072 (2002).

Krumholz, H. M. Readmission after hospitalization for congestive heart failure among Medicare beneficiaries. Arch. Intern. Med. 157, 99–104 (1997).

Giamouzis, G. et al. Hospitalization epidemic in patients with heart failure: risk factors, risk prediction, knowledge gaps, and future directions. J. Card. Fail. 17, 54–75 (2011).

Ross, J. S. et al. Recent national trends in readmission rates after heart failure hospitalization. Circ. Heart Fail. 3, 97–103 (2010).

Roger, V. L. Epidemiology of heart failure. Circ. Res. 113, 646–659 (2013).

Callender, T. et al. Heart failure care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 11, e1001699 (2014).

Bui, A. L., Horwich, T. B. & Fonarow, G. C. Epidemiology and risk profile of heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 8, 30–41 (2010).

Ho, J. E. et al. Predicting heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction: the International Collaboration on Heart Failure Subtypes. Circ. Heart Fail. 9, e003116 (2016).

McMurray, J. J. V. et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 33, 1787–1847 (2012).

Levy, D., Larson, M. G., Vasan, R. S., Kannel, W. B. & Ho, K. K. The progression from hypertension to congestive heart failure. JAMA 275, 1557–1562 (1996).

Bloom, M. W. et al. Cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction and heart failure: part 1: definitions, pathophysiology, risk factors, and imaging. Circ. Heart Fail. 9, e002661 (2016).

Mazurek, J. A. & Jessup, M. Understanding heart failure. Heart Fail. Clin. 13, 1–19 (2017).

Chatterjee, N. A. & Fifer, M. A. in Pathophysiology of Heart Disease (ed. Lilly, L. S. ) 216–243 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010).

Page, R. L. et al. Drugs that may cause or exacerbate heart failure. Circulation 134, e32–e69 (2016).

Gaggin, H. K. & Dec, G. W. in Hurst's The Heart: 50th Anniversary Edition (eds Fuster, V., Harrington, R. A., Narula, J. & Eapen, Z. J. ) Ch. 68 (McGraw-Hill, 2017).

Kalogeropoulos, A. P. et al. Characteristics and outcomes of adult outpatients with heart failure and improved or recovered ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 1, 510–518 (2016).

Hartupee, J. & Mann, D. L. Neurohormonal activation in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 14, 30–38 (2016).

Díez, J. Chronic heart failure as a state of reduced effectiveness of the natriuretic peptide system: implications for therapy. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 19, 167–176 (2017).

Prabhu, S. D. & Frangogiannis, N. G. The biological basis for cardiac repair after myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 119, 91–112 (2016).

Sekaran, N. K., Crowley, A. L., de Souza, F. R., Resende, E. S. & Rao, S. V. The role for cardiovascular remodeling in cardiovascular outcomes. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 19, 23 (2017).

Hsiao, R. & Greenberg, B. Contemporary treatment of acute heart failure. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 58, 367–378 (2016).

Davie, A. P. et al. Value of the electrocardiogram in identifying heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction. BMJ 312, 222 (1996).

Nohria, A. et al. Clinical assessment identifies hemodynamic profiles that predict outcomes in patients admitted with heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 41, 1797–1804 (2003). A guide to bedside haemodynamic assessment in patients with heart failure.

Yancy, C. W. et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 70, 776–803 (2017). Most recent update to the ACC, AHA and HFSA comprehensive guidelines addressing the use of novel agents such as sacubitril/valsartan, as well as addressing the role of biomarkers in the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of heart failure.

Januzzi, J. L. & Troughton, R. Are serial BNP measurements useful in heart failure management?: Serial natriuretic peptide measurements are useful in heart failure management. Circulation 127, 500–508 (2013).

Ahmad, T. et al. Evaluation of the incremental prognostic utility of increasingly complex testing in chronic heart failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 8, 709–716 (2015).

Mestroni, L. Guidelines for the study of familial dilated cardiomyopathies. Eur. Heart J. 20, 93–102 (1999).

Pérez-Serra, A. et al. Genetic basis of dilated cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Cardiol. 224, 461–472 (2016).

Cooper, L. T. et al. The role of endomyocardial biopsy in the management of cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 50, 1914–1931 (2007).

American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force et al. ACCF/ASE/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCM/SCCT/SCMR 2011 appropriate use criteria for echocardiography. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Endorsed by the American College of Chest Physicians. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 57, 1126–1166 (2011).

Gardin, J. M. et al. M-mode echocardiographic predictors of six- to seven-year incidence of coronary heart disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, and mortality in an elderly cohort (the cardiovascular health study). Am. J. Cardiol. 87, 1051–1057 (2001).

Grayburn, P. A. et al. Echocardiographic predictors of morbidity and mortality in patients with advanced heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 45, 1064–1071 (2005).

American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force et al. ACCF/ASE/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCM/SCCT/SCMR 2011 appropriate use criteria for echocardiography. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance American College of Chest Physicians. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 24, 229–267 (2011).

Thomas, J. T. et al. Utility of history, physical examination, electrocardiogram, and chest radiograph for differentiating normal from decreased systolic function in patients with heart failure. Am. J. Med. 112, 437–445 (2002).

Miller, W. L. & Mullan, B. P. Understanding the heterogeneity in volume overload and fluid distribution in decompensated heart failure is key to optimal volume management. JACC Heart Fail. 2, 298–305 (2014).

Ko, S. M., Hwang, H. K., Kim, S. M. & Cho, I. H. Multi-modality imaging for the assessment of myocardial perfusion with emphasis on stress perfusion CT and MR imaging. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 31, 1–21 (2015).

Kalisz, K. & Rajiah, P. Impact of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in non-ischemic cardiomyopathies. World J. Cardiol. 8, 132–145 (2016).

Milani, R. V. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing: how do we differentiate the cause of dyspnea? Circulation 110, e27–e31 (2004).

Mancini, D. M. et al. Value of peak exercise oxygen consumption for optimal timing of cardiac transplantation in ambulatory patients with heart failure. Circulation 83, 778–786 (1991).

Corrà, U. et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in systolic heart failure in 2014: the evolving prognostic role. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 16, 929–941 (2014).

Gidwani, U. K., Mohanty, B. & Chatterjee, K. The pulmonary artery catheter. Cardiol. Clin. 31, 545–565 (2013).

Ammar, K. A. et al. Prevalence and prognostic significance of heart failure stages: application of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Heart Failure Staging Criteria in the Community. Circulation 115, 1563–1570 (2007).

New York Heart Association. Nomenclature and Criteria for Diagnosis of Diseases of the Heart and Great Vessels (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1994).

Goldman, L., Hashimoto, B., Cook, E. F. & Loscalzo, A. Comparative reproducibility and validity of systems for assessing cardiovascular functional class: advantages of a new specific activity scale. Circulation 64, 1227–1234 (1981).

SPRINT Research Group et al. Randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 2103–2116 (2015).

Yancy, C. W. et al. 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update on new pharmacological therapy for heart failure: an update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 68, 1476–1488 (2016).

Ponikowski, P. et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 37, 2129–2200 (2016).

Maggioni, A. P. et al. Are hospitalized or ambulatory patients with heart failure treated in accordance with European Society of Cardiology guidelines? Evidence from 12 440 patients of the ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 15, 1173–1184 (2013).

McMurray, J. J. V. et al. Angiotensin–neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 993–1004 (2014). A landmark heart failure trial that compared sacubitril/valsartan with enalapril therapy.

Kjekshus, J. et al. Rosuvastatin in older patients with systolic heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 2248–2261 (2007).

Tavazzi, L. Effect of rosuvastatin in patients with chronic heart failure (the GISSI-HF trial): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 372, 1231–1239 (2008).

McMurray, J. J. V. et al. Aliskiren, enalapril, or aliskiren and enalapril in heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 374, 1521–1532 (2016).

Goldstein, R. E., Boccuzzi, S. J., Cruess, D. & Nattel, S. Diltiazem increases late-onset congestive heart failure in postinfarction patients with early reduction in ejection fraction. The Adverse Experience Committee; and the Multicenter Diltiazem Postinfarction Research Group. Circulation 83, 52–60 (1991).

Hernandez, A. V., Usmani, A., Rajamanickam, A. & Moheet, A. Thiazolidinediones and risk of heart failure in patients with or at high risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 11, 115–128 (2011).

Scott, P. A., Kingsley, G. H. & Scott, D. L. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cardiac failure: meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised controlled trials. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 10, 1102–1107 (2008).

Crespo-Leiro, M. G. et al. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long-Term Registry (ESC-HF-LT): 1-year follow-up outcomes and differences across regions. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 18, 613–625 (2016).

Epstein, A. E. et al. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: executive summary. Heart Rhythm 5, 934–955 (2008).

Connolly, S. Meta-analysis of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator secondary prevention trials. Eur. Heart J. 21, 2071–2078 (2000).

Moss, A. J. et al. Prophylactic Implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 877–883 (2002).

Bardy, G. H. et al. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter–defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 225–237 (2005).

Desai, A. S., Fang, J. C., Maisel, W. H. & Baughman, K. L. Implantable defibrillators for the prevention of mortality in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy. JAMA 292, 2874–2879 (2004).

Kadish, A. et al. Prophylactic defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 2151–2158 (2004).

Yancy, C. W. et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 128, e240–e327 (2013).

Køber, L. et al. Defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic systolic heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 1221–1230 (2016).

McMurray, J. J. V. The ICD in heart failure — time for a rethink? N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 1283–1284 (2016).

Cleland, J. G. F. et al. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 1539–1549 (2005).

Cleland, J. G. F. et al. Longer-term effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy on mortality in heart failure [the CArdiac REsynchronization-Heart Failure (CARE-HF) trial extension phase]. Eur. Heart J. 27, 1928–1932 (2006).

Bristow, M. R. et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 2140–2150 (2004).

Cleland, J. G. et al. An individual patient meta-analysis of five randomized trials assessing the effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy on morbidity and mortality in patients with symptomatic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 34, 3547–3556 (2013).

Tracy, C. M. et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 61, e6–e75 (2013).

Barold, S. S. & Herweg, B. Cardiac resynchronization in patients with atrial fibrillation. J. Atr. Fibrillation 8, 1383 (2015).

Upadhyay, G. A., Choudhry, N. K., Auricchio, A., Ruskin, J. & Singh, J. P. Cardiac resynchronization in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 52, 1239–1246 (2008).

Fang, J. C. et al. Advanced (stage D) heart failure: a statement from the Heart Failure Society of America Guidelines Committee. J. Card. Fail. 21, 519–534 (2015). A comprehensive paper on advanced heart failure, allowing a better understanding of this population of patients, underscoring current knowledge gaps and the importance of leading clinical research on this topic.

Slaughter, M. S. et al. Advanced heart failure treated with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 2241–2251 (2009). A landmark trial reporting the results of pulsatile versus continuous flow LVADs in patients ineligible for transplants.

Aaronson, K. D. et al. Use of an intrapericardial, continuous-flow, centrifugal pump in patients awaiting heart transplantation. Circulation 125, 3191–3200 (2012).

Starling, R. C. et al. Results of the post-U. S. Food and Drug Administration-approval study with a continuous flow left ventricular assist device as a bridge to heart transplantation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 57, 1890–1898 (2011). A post-market trial reporting the results of the use of HM II LVAD as a bridge to transplantation, confirming the results of the original pivotal clinical trial.

Estep, J. D. et al. Risk assessment and comparative effectiveness of left ventricular assist device and medical management in ambulatory heart failure patients. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 66, 1747–1761 (2015).

Kirklin, J. K. et al. Seventh INTERMACS annual report: 15,000 patients and counting. J. Hear. Lung Transplant. 34, 1495–1504 (2015).

Carpentier, A. et al. First clinical use of a bioprosthetic total artificial heart: report of two cases. Lancet 386, 1556–1563 (2015).

Mehra, M. R. et al. Listing criteria for heart transplantation: International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines for the care of cardiac transplant candidates — 2006. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 25, 1024–1042 (2006). A guideline statement on listing criteria for patients considered for cardiac transplantation.

Feldman, D. et al. The 2013 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines for mechanical circulatory support: executive summary. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 32, 157–187 (2013).

Mehra, M. R. et al. The 2016 International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation listing criteria for heart transplantation: a 10-year update. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 35, 1–23 (2016).

Slaughter, M. S. et al. Clinical management of continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices in advanced heart failure. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 29, S1–S39 (2010).

Ziemba, E. A. & John, R. Mechanical circulatory support for bridge to decision: which device and when to decide. J. Card. Surg. 25, 425–433 (2010).

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Decision memo for ventricular assist devices for bridge-to-transplant and destination therapy (CAG-00432R). CMShttps://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=268 (2013).

Stevenson, L. W. et al. INTERMACS profiles of advanced heart failure: the current picture. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 28, 535–541 (2009). A founding paper that allows a better understanding and clinical profiling of patients who are NYHA class IV.

Mehra, M. R. et al. A fully magnetically levitated circulatory pump for advanced heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 440–450 (2017).

de By, T. M. M. H. et al. The European Registry for Patients with Mechanical Circulatory Support (EUROMACS): first annual report. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 47, 770–777 (2015).

Lund, L. H. et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty-third adult heart transplantation report? Focus theme: primary diagnostic indications for transplant. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 35, 1158–1169 (2016).

Lund, L. H. et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty-second official adult heart transplantation report? Focus theme: early graft failure. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 34, 1244–1254 (2015).

Lund, L. H. et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty-first official adult heart transplant report — focus theme: retransplantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 33, 996–1008 (2014).

Samsky, M. D. et al. Ten-year experience with extended criteria cardiac transplantation. Circ. Heart Fail. 6, 1230–1238 (2013).

Samara, M. A. & Wilson Tang, W. H. Device monitoring strategies in acute heart failure syndromes. Heart Fail. Rev. 16, 491–502 (2011).

Anker, S. D., Koehler, F. & Abraham, W. T. Telemedicine and remote management of patients with heart failure. Lancet 378, 731–739 (2011).

Emani, S. Remote monitoring to reduce heart failure readmissions. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 14, 40–47 (2017).

Dierckx, R., Pellicori, P., Cleland, J. G. F. & Clark, A. L. Telemonitoring in heart failure: BigBrother watching over you. Heart Fail. Rev. 20, 107–116 (2014).

Inglis, S. C., Clark, R. A., McAlister, F. A., Stewart, S. & Cleland, J. G. F. Which components of heart failure programmes are effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the outcomes of structured telephone support or telemonitoring as the primary component of chronic heart failure management in 8323 patients: abridged Cochrane review. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 13, 1028–1040 (2011).

Inglis, S. C., Clark, R. A., Dierckx, R., Prieto-Merino, D. & Cleland, J. G. F. Structured telephone support or non-invasive telemonitoring for patients with heart failure. Heart 103, 255–257 (2017).

Inglis, S. C., Clark, R. A., Dierckx, R., Prieto-Merino, D. & Cleland, J. G. Structured telephone support or non-invasive telemonitoring for patients with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10, CD007228 (2015).

Cleland, J. G. F., Lewinter, C. & Goode, K. M. Telemonitoring for heart failure: the only feasible option for good universal care? Eur. J. Heart Fail. 11, 227–228 (2009).

Hawkins, N. M. et al. Predicting heart failure decompensation using cardiac implantable electronic devices: a review of practices and challenges. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 18, 977–986 (2016).

Adamson, P. B., Ginn, G., Anker, S. D., Bourge, R. C. & Abraham, W. T. Remote haemodynamic-guided care for patients with chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis of completed trials. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 19, 426–433 (2017).

Abraham, W. T. et al. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 377, 658–666 (2011).

Gaggin, H. K. & Januzzi, J. L. Biomarkers and diagnostics in heart failure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1832, 2442–2450 (2013).

Ahmad, T. et al. Charting a roadmap for heart failure biomarker studies. JACC Heart Fail. 2, 477–488 (2014).

Motiwala, S. R. & Januzzi, J. L. The role of natriuretic peptides as biomarkers for guiding the management of chronic heart failure. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 93, 57–67 (2012).

Januzzi, J. L. et al. Use of amino-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide to guide outpatient therapy of patients with chronic left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 58, 1881–1889 (2011).

Bhardwaj, A. et al. Quality of life and chronic heart failure therapy guided by natriuretic peptides: results from the ProBNP Outpatient Tailored Chronic Heart Failure Therapy (PROTECT) study. Am. Heart J. 164, 793–799.e1 (2012).

Weiner, R. B. et al. Improvement in structural and functional echocardiographic parameters during chronic heart failure therapy guided by natriuretic peptides: mechanistic insights from the ProBNP Outpatient Tailored Chronic Heart Failure (PROTECT) study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 15, 342–351 (2013).

Felker, G. M. et al. Rationale and design of the GUIDE-IT study. JACC Heart Fail. 2, 457–465 (2014).

Gaggin, H. K. et al. Head-to-head comparison of serial soluble ST2, growth differentiation factor-15, and highly-sensitive troponin T measurements in patients with chronic heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2, 65–72 (2014).

Motiwala, S. R. et al. Serial measurement of galectin-3 in patients with chronic heart failure: results from the ProBNP Outpatient Tailored Chronic Heart Failure Therapy (PROTECT) study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 15, 1157–1163 (2013).

Wu, A. H. B., Wians, F. & Jaffe, A. Biological variation of galectin-3 and soluble ST2 for chronic heart failure: Implication on interpretation of test results. Am. Heart J. 165, 995–999 (2013).

Januzzi, J. L., Pascual-Figal, D. & Daniels, L. B. ST2 testing for chronic heart failure therapy monitoring: the International ST2 Consensus Panel. Am. J. Cardiol. 115, 70B–75B (2015).

Gandhi, P. U. et al. Galectin-3 and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist use in patients with chronic heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Am. Heart J. 169, 404–411.e3 (2015).

Meijers, W. C. et al. Variability of biomarkers in patients with chronic heart failure and healthy controls. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 19, 357–365 (2017).

Krumholz, H. M. A. Taxonomy for disease management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Disease Management Taxonomy Writing Group. Circulation 114, 1432–1445 (2006).

Rich, M. W. et al. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 333, 1190–1195 (1995).

Stromberg, A. Nurse-led heart failure clinics improve survival and self-care behaviour in patients with heart failure. Results from a prospective, randomised trial. Eur. Heart J. 24, 1014–1023 (2003).

Stewart, S., Pearson, S. & Horowitz, J. D. Effects of a home-based intervention among patients with congestive heart failure discharged from acute hospital care. Arch. Intern. Med. 158, 1067–1072 (1998).

Takeda, A. et al. Clinical service organisation for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9, CD002752 (2012).

McAlister, F. A., Stewart, S., Ferrua, S. & McMurray, J. J. J. V. Multidisciplinary strategies for the management of heart failure patients at high risk for admission. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 44, 810–819 (2004).

Fonarow, G. C. et al. Heart failure care in the outpatient cardiology practice setting: findings from IMPROVE HF. Circ. Heart Fail. 1, 98–106 (2008).

Lee, D. S. et al. Risk–treatment mismatch in the pharmacotherapy of heart failure. JAMA 294, 1240–1247 (2005).

Lesman-Leegte, I. et al. Quality of life and depressive symptoms in the elderly: a comparison between patients with heart failure and age- and gender-matched community controls. J. Card. Fail. 15, 17–23 (2009).

Juenger, J. Health related quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure: comparison with other chronic diseases and relation to functional variables. Heart 87, 235–241 (2002).

Jaarsma, T., Johansson, P., Agren, S. & Stromberg, A. Quality of life and symptoms of depression in advanced heart failure patients and their partners. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 4, 233–237 (2010).

Li, C.-C. & Shun, S.-C. Understanding self care coping styles in patients with chronic heart failure: a systematic review. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 15, 12–19 (2016).

Obiegło, M., Uchmanowicz, I., Wleklik, M., Jankowska-Polan´ska, B. & Kus´mierz, M. The effect of acceptance of illness on the quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 15, 241–247 (2016).

Thompson, D. R., Ski, C. F., Garside, J. & Astin, F. A review of health-related quality of life patient-reported outcome measures in cardiovascular nursing. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 15, 114–125 (2016).

Anker, S. D. et al. The importance of patient-reported outcomes: a call for their comprehensive integration in cardiovascular clinical trials. Eur. Heart J. 35, 2001–2009 (2014).

Kraai, I. H. et al. Preferences of heart failure patients in daily clinical practice: quality of life or longevity? Eur. J. Heart Fail. 15, 1113–1121 (2013).

Stevenson, L. W. et al. Changing preferences for survival after hospitalization with advanced heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 52, 1702–1708 (2008).

Brunner- La Rocca, H.-P. et al. End-of-life preferences of elderly patients with chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 33, 752–759 (2011).

Iqbal, J., Francis, L., Reid, J., Murray, S. & Denvir, M. Quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure and their carers: a 3-year follow-up study assessing hospitalization and mortality. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 12, 1002–1008 (2010).

Hoekstra, T. et al. Quality of life and survival in patients with heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 15, 94–102 (2013).

Jonkman, N. H. et al. Do self-management interventions work in patients with heart failure? An individual patient data meta-analysis. Circulation 133, 1189–1198 (2016).

Mohammed, M. A., Moles, R. J. & Chen, T. F. Impact of pharmaceutical care interventions on health-related quality-of-life outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Pharmacother. 50, 862–881 (2016).

Jensen, L. et al. Improving heart failure outcomes in ambulatory and community care: a scoping study. Med. Care Res. Rev.http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077558716655451 (2016).

Pandey, A. et al. Exercise training in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Circ. Heart Fail. 8, 33–40 (2014).

Ponikowski, P. et al. Heart failure: preventing disease and death worldwide. ESC Heart Fail. 1, 4–25 (2014).

Anwar, M. S. et al. The future of pharmacogenetics in the treatment of heart failure. Pharmacogenomics 16, 1817–1827 (2015).

Zacchigna, S., Zentilin, L. & Giacca, M. Adeno-associated virus vectors as therapeutic and investigational tools in the cardiovascular system. Circ. Res. 114, 1827–1846 (2014).

Pulicherla, N. et al. Engineering liver-detargeted AAV9 vectors for cardiac and musculoskeletal gene transfer. Mol. Ther. 19, 1070–1078 (2011).

Boecker, W. et al. Cardiac-specific gene expression facilitated by an enhanced myosin light chain promoter. Mol. Imaging 3, 69–75 (2004).

Muller, O. et al. Improved cardiac gene transfer by transcriptional and transductional targeting of adeno-associated viral vectors. Cardiovasc. Res. 70, 70–78 (2006).

Ishikawa, K., Aguero, J., Naim, C., Fish, K. & Hajjar, R. J. Percutaneous approaches for efficient cardiac gene delivery. J. Cardiovasc. Transl Res. 6, 649–659 (2013).

Jessup, M. et al. Calcium upregulation by percutaneous administration of gene therapy in cardiac disease (CUPID): a phase 2 trial of intracoronary gene therapy of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation 124, 304–313 (2011).

Zsebo, K. et al. Long-term effects of AAV1/SERCA2a gene transfer in patients with severe heart failure: analysis of recurrent cardiovascular events and mortality. Circ. Res. 114, 101–108 (2014).

Pleger, S. T. et al. Cardiac AAV9-S100A1 gene therapy rescues post-ischemic heart failure in a preclinical large animal model. Sci. Transl Med. 3, 92ra64 (2011).

Lai, N. C. Intracoronary adenovirus encoding adenylyl cyclase VI increases left ventricular function in heart failure. Circulation 110, 330–336 (2004).

Kelkar, A. A. et al. Mechanisms contributing to the progression of ischemic and nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 66, 2038–2047 (2015).

Fisher, S. A., Doree, C., Mathur, A. & Martin-Rendon, E. Meta-analysis of cell therapy trials for patients with heart failure. Circ. Res. 116, 1361–1377 (2015).

Landin, A. M. & Hare, J. M. The quest for a successful cell-based therapeutic approach for heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 38, ehw626 (2017).

Segers, V. F. M. & Lee, R. T. Biomaterials to enhance stem cell function in the heart. Circ. Res. 109, 910–922 (2011).

Stevenson, L. W. The limited reliability of physical signs for estimating hemodynamics in chronic heart failure. JAMA 261, 884–888 (1989).

Felker, G. M., Cuculich, P. S. & Gheorghiade, M. The Valsalva maneuver: a bedside ‘biomarker’ for heart failure. Am. J. Med. 119, 117–122 (2006).

Harinstein, M. E. et al. Clinical assessment of acute heart failure syndromes: emergency department through the early post-discharge period. Heart 97, 1607–1618 (2011).

Leier, C. V. & Chatterjee, K. The physical examination in heart failure — part, I. Congest. Heart Fail. 13, 41–47 (2007).

Leier, C. V. Nuggets, pearls, and vignettes of master heart failure clinicians. Congest. Heart Fail. 7, 297–308 (2001).

Caldentey, G. et al. Prognostic value of the physical examination in patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation. JACC Heart Fail. 2, 15–23 (2014).

Kaye, D. M. & Krum, H. Drug discovery for heart failure: a new era or the end of the pipeline? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6, 127–139 (2007).

Triposkiadis, F. et al. Reframing the association and significance of co-morbidities in heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 18, 744–758 (2016).

Mentz, R. J. & Felker, G. M. Noncardiac comorbidities and acute heart failure patients. Heart Fail. Clin. 9, 359–367 (2013).

Skrtic, S., Cabrera, C., Olsson, M., Schnecke, V. & Lind, M. Contemporary risk estimates of three HbA 1c variables in relation to heart failure following diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Heart 103, 353–358 (2016).

Swan, J. W. et al. Insulin resistance in chronic heart failure: relation to severity and etiology of heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 30, 527–532 (1997).

Vargas-Uricoechea, H. & Bonelo-Perdomo, A. Thyroid dysfunction and heart failure: mechanisms and associations. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 14, 48–58 (2017).

Mentz, R. J. & O’Connor, C. M. Pathophysiology and clinical evaluation of acute heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 13, 28–35 (2016).

Swedberg, K. et al. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet 376, 875–885 (2010).

Faris, R. F., Flather, M., Purcell, H., Poole-Wilson, P. A. & Coats, A. J. Diuretics for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2, CD003838 (2012).

Hart, R. G., Pearce, L. A. & Aguilar, M. I. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann. Intern. Med. 146, 857–867 (2007).

Digitalis Investigation Group. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 336, 525–533 (1997).

Tavazzi, L. et al. Effect of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in patients with chronic heart failure (the GISSI-HF trial): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 372, 1223–1230 (2008).

Lewis, G. F. & Gold, M. R. Clinical experience with subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 12, 398–405 (2015).

Abraham, W. T. & Smith, S. A. Devices in the management of advanced, chronic heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 10, 98–110 (2013).

Acknowledgements

J.B. received research support from the US National Institutes of Health, European Union and the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Introduction (J.B., M.W.B. and J.-N.T.); Epidemiology (J.B., M.W.B. and C.S.P.L.); Mechanisms/pathophysiology (M.W.B., J.L.J., A.P.M. and J.-N.T.); Diagnosis, screening and prevention (M.W.B., B.G., J.L.J., A.P.M. and J.T.); Management (M.W.B., B.G., C.S.P.L. and T.J.); Quality of life (T.J.); Outlook (J.B.); Overview of Primer (J.B.).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.W.B. has received speaker's bureau from Novartis Pharmaceuticals. B.G. has acted as a consultant for Teva Pharmaceuticals, Mesoblast, Celadon, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Janssen and AstraZeneca. J.L.J. has received research support from Roche Diagnostics, Siemens, Prevencio and Singulex; consulting income from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis and Janssen; and participates on cardiology endpoint committees and/or data safety monitoring boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Novartis, Pfizer and Janssen. C.S.P.L. has received research support from Boston Scientific, Bayer, Thermofisher, Medtronic and Vifor Pharma; and has acted as a consultant for Bayer, Novartis, Takeda, Merck, AstraZeneca, Janssen Research & Development, LLC, Menarini, Boehringer Ingelheim and Abbott Diagnostics. A.P.M. has received honoraria for the participation in committees of trials sponsored by Novartis, Bayer, Cardiorentis and Fresenius. J.-N.T. has received research grants from Novartis, Carmat and Abbott; and has consulted for Abbott, Amgen, Bayer, Carmat, Daichi, Heartware, Novartis, Vifor Pharma, Sankyo and Resmed. J.B. is a consultant for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CVRx, Janssen, Luitpold, Medtronic, Novartis, Relypsa and ZS Pharma. T.J. has received honoraria for the participation in committees of projects sponsored by Novartis.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bloom, M., Greenberg, B., Jaarsma, T. et al. Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Nat Rev Dis Primers 3, 17058 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.58

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.58

This article is cited by

-

Association between the triglyceride–glucose index and left ventricular global longitudinal strain in patients with coronary heart disease in Jilin Province, China: a cross-sectional study

Cardiovascular Diabetology (2023)

-

Metabolic mechanisms in physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy: new paradigms and challenges

Nature Reviews Cardiology (2023)

-

MiR-568 mitigated cardiomyocytes apoptosis, oxidative stress response and cardiac dysfunction via targeting SMURF2 in heart failure rats

Heart and Vessels (2023)

-

Predictors of mortality in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: interaction between diabetes mellitus and impaired renal function

International Urology and Nephrology (2023)

-

Effects of diabetes mellitus on left ventricular function and remodeling in hypertensive patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: assessment with 3.0 T MRI feature tracking

Cardiovascular Diabetology (2022)