Key Points

-

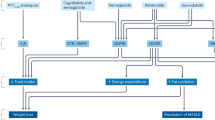

The metabolic syndrome is a clustering of factors associated with an increased risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. The core 'metabolic risk factors' are atherogenic dyslipidaemia, elevated blood pressure, elevated plasma glucose, a prothrombotic state and a pro-inflammatory state, each of which has several components.

-

There are two potential therapeutic approaches to the metabolic syndrome. One strategy is to identify each risk factor separately and to treat this risk factor unrelated to its clustering with other risk factors. The alternative strategy is to target all or multiple risk factors with single therapies.

-

The former strategy will continue to be part of effective therapies, but, increasingly, the latter approach is attractive and available. This article explores the latter approach, with an emphasis on the potential utility of drug therapy for the metabolic syndrome.

-

Each of the risk factors of the metabolic syndrome is considered as a possible primary drug target, and potential secondary or tertiary targets are also discussed. Emphasis is placed on the development of multifunctional drugs that could alleviate problems with polypharmacy.

Abstract

The metabolic syndrome — a collection of factors associated with increased risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes — is becoming increasingly common, largely as a result of the increase in the prevalence of obesity. Although it is generally agreed that first-line clinical intervention for the metabolic syndrome is lifestyle change, this is insufficient to normalize the risk factors in many patients, and so residual risk could be high enough to justify drug therapy. However, at present there are no approved drugs that can reliably reduce all of the metabolic risk factors over the long term, and so there is growing interest in therapeutic strategies that might target multiple risk factors more effectively, thereby minimizing problems with polypharmacy. This review summarizes current understanding of the nature of the metabolic syndrome, and discusses each of the risk factors of the metabolic syndrome as possible primary drug targets; potential secondary or tertiary targets are also considered.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Final Report. Circulation 106, 3143–3421 (2002). The 2001 NCEP report sparked increased interest of the medical community in the metabolic syn-drome. It led to new research as well as controversy about the clinical utility of the syndrome.

Grundy, S. M. et al. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation 109, 433–438 (2004).

Grundy, S. M. et al. Clinical management of metabolic syndrome: report of the American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Diabetes Association conference on scientific issues related to management. Circulation 109, 551–556 (2004).

Eckel, R. H., Grundy, S. M. & Zimmet, P. Z. The metabolic syndrome: epidemiology, mechanisms, and therapy. Lancet 365, 1415–1428 (2005). Reviews the worldwide epidemiology, pathophysiology and management of the metabolic syndrome.

Isomaa, B. et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care 24, 683–689 (2001).

Lakka, H. M. et al. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA 288, 2709–2716 (2002).

Sattar, N. et al. Metabolic syndrome with and without C-reactive protein as a predictor of coronary heart disease and diabetes in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. Circulation 108, 414–419 (2003).

Girman, C. J. et al. The metabolic syndrome and risk of major coronary events in the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) and the Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (AFCAPS/TexCAPS). Am. J. Cardiol. 93, 136–141 (2004).

Malik, S. et al. Impact of the metabolic syndrome on mortality from coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease, and all causes in United States adults. Circulation 110, 1245–1250 (2004).

Olijhoek, J. K. et al. The metabolic syndrome is associated with advanced vascular damage in patients with coronary heart disease, stroke, peripheral arterial disease or abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur. Heart J. 25, 342–348 (2004).

Alexander, C. M. et al. NCEP-defined metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and prevalence of coronary heart disease among NHANES III participants age 50 years and older. Diabetes 52, 1210–1214 (2003). Shows that most patients with type 2 diabetes have the metabolic syndrome, and the syndrome accounts for most of the increased risk for coronary heart disease resulting from diabetes.

Ninomiya, J. K. et al. Association of the metabolic syndrome with history of myocardial infarction and stroke in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Circulation 109, 42–46 (2004).

McNeill, A. M. et al. The metabolic syndrome and 11-year risk of incident cardiovascular disease in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes Care 28, 385–390 (2005).

Solymoss, B. C. et al. Incidence and clinical characteristics of the metabolic syndrome in patients with coronary artery disease. Coron. Artery Dis. 14, 207–212 (2003).

Turhan, H. et al. High prevalence of metabolic syndrome among young women with premature coronary artery disease. Coron. Artery Dis. 16, 37–40 (2005).

Stern, M. et al. Does the metabolic syndrome improve identification of individuals at risk of type 2 diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease? Diabetes Care 27, 2676–2681 (2004). Reports that the metabolic syndrome increases the risk for type 2 diabetes by about fivefold.

Grundy, S. M. et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome. An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation 112, 2735–2752 (2005).

Ruderman, N., Chisholm, D., Pi-Sunyer, X. & Schneider, S. The metabolically obese, normal-weight individual revisited. Diabetes 47, 699–713 (1998).

Kahn, R., Buse, J., Ferrannini, E. & Stern, M. The metabolic syndrome: time for a critical appraisal: joint statement from the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 28, 2289–2304 (2005).

Knowler, W. C. et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 393–403 (2002).

Tuomilehto, J. et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1343–1350 (2001).

Pan, X. R. et al. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance: the Da Qing IGT and diabetes study. Diabetes Care 20, 537–544 (1997).

Rollason, V. & Vogt, N. Reduction of polypharmacy in the elderly: a systematic review of the role of the pharmacist. Drugs Aging 20, 817–832 (2003).

Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults — The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes. Res. 6 (Suppl. 2), 51–209 (1998). Presents evidence-based guidelines on the management of obesity in patients at risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

Berg, A. H. & Scherer, P. E. Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 96, 939–949 (2005).

Matsuzawa, Y. Adipocytokines and metabolic syndrome. Semin. Vasc. Med. 5, 34–39 (2005).

Trayhurn, P. & Wood, I. S. Adipokines: inflammation and the pleiotropic role of white adipose tissue. Br. J. Nutr. 92, 347–355 (2004).

Nawrocki, A. R. & Scherer, P. E. Keynote review: the adipocyte as a drug discovery target. Drug Discov. Today 10, 1219–1230 (2005).

Arterburn, D. E., Crane, P. K. & Veenstra, D. L. The efficacy and safety of sibutramine for weight loss: a systematic review. Arch. Intern. Med. 164, 994–1003 (2004).

Di Marzo, V. & Matias, I. Endocannabinoid control of food intake and energy balance. Nature Neurosci. 8, 585–589 (2005).

Black, S. C. Cannabinoid receptor antagonists and obesity. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 5, 389–394 (2004).

Van Gaal, L. F. et al. Effects of cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker rimonabant on weight reduction and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight patients: 1-year experience from the RIO-Europe study. Lancet 365, 1389–1397 (2005).

Osei-Hyiaman, D. et al. Endocannabinoid activation at hepatic CB1 receptors stimulates fatty acid synthesis and contributes to diet-induced obesity. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 1298–1305 (2005).

Bensaid, M. et al. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716 increases Acrp30 mRNA expression in adipose tissue of obese fa/fa rats and in cultured adipocyte cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 63, 908–914 (2003).

Despres, J. P., Golay, A. & Sjostrom, L. Rimonabant in Obesity-Lipids Study Group. Effects of rimonabant on metabolic risk factors in overweight patients with dyslipidemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 2121–2134 (2005).

Cota, D. et al. The endogenous cannabinoid system affects energy balance via central orexigenic drive and peripheral lipogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 423–443 (2003).

Osei-Hyiaman, D. et al. Endocannabinoid activation at hepatic CB1 receptors stimulates fatty acid synthesis and contributes to diet-induced obesity. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 1298–1305 (2005).

Curran, M. P. & Scott, L. J. Orlistat: a review of its use in the management of patients with obesity. Drugs 64, 2845–2864 (2004).

Ridker, P. M. Connecting the role of C-reactive protein and statins in cardiovascular disease. Clin. Cardiol. 26 (Suppl. 3), 39–44 (2003).

Jialal, I. et al. Effect of hydroxymethyl glutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitor therapy on high sensitive C-reactive protein levels. Circulation 103, 1933–1935 (2001).

Robinson, J. G., Smith, B., Maheshwari, N. & Schrott, H. Pleiotropic effects of statins: benefit beyond cholesterol reduction? A meta-regression analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 46, 1855–1862 (2005).

Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 360, 7–22 (2002). Documents the benefit of cholesterol lowering in high-risk patients including those with diabetes.

LaRosa, J. C. et al. Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 1425–1435 (2005).

Hunninghake, D. et al. Coadministration of colesevelam hydrochloride with atorvastatin lowers LDL cholesterol additively. Atherosclerosis 158, 407–416 (2001).

Pearson, T. A. et al. A community-based, randomized trial of ezetimibe added to statin therapy to attain NCEP ATP III goals for LDL cholesterol in hypercholesterolemic patients: the ezetimibe add-on to statin for effectiveness (EASE) trial. Mayo Clin. Proc. 80, 587–595 (2005).

Ballantyne, C. M., Abate, N., Yuan, Z., King, T. R. & Palmisano, J. Dose-comparison study of the combination of ezetimibe and simvastatin (Vytorin) versus atorvastatin in patients with hypercholesterolemia: the Vytorin Versus Atorvastatin (VYVA) study. Am. Heart J. 149, 464–473 (2005).

Law, M. R., Wald, N. J. & Thompson, S. G. By how much and how quickly does reduction in serum cholesterol concentration lower risk of ischaemic heart disease? BMJ 308, 367–372 (1994).

Canner, P. L., Furberg, C. D., Terrin, M. L. & McGovern, M. E. Benefits of niacin by glycemic status in patients with healed myocardial infarction (from the Coronary Drug Project). Am. J. Cardiol. 95, 254–257 (2005). Demonstrates the benefit of nicotinic acid in patients with impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes.

Taylor, A. J., Sullenberger, L. E., Lee, H. J., Lee, J. K. & Grace, K. A. Arterial Biology for the Investigation of the Treatment Effects of Reducing Cholesterol (ARBITER) 2: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of extended-release niacin on atherosclerosis progression in secondary prevention patients treated with statins. Circulation 110, 3512–3517 (2004).

Bays, H. E. et al. ADvicor Versus Other Cholesterol-Modulating Agents Trial Evaluation. Comparison of once-daily, niacin extended-release/lovastatin with standard doses of atorvastatin and simvastatin (the ADvicor Versus Other Cholesterol-Modulating Agents Trial Evaluation [ADVOCATE]). Am. J. Cardiol. 91, 667–672 (2003).

Staels, B. & Fruchart, J. C. Therapeutic roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists. Diabetes 54, 2460–2470 (2005).

Gervois, P., Torra, I. P., Fruchart, J. C. & Staels, B. Regulation of lipid and lipoprotein metabolism by PPAR activators. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 38, 3–11 (2000).

Grundy, S. M. et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of simvastatin plus fenofibrate for combined hyperlipidemia (the SAFARI trial). J. Cardiol. 95, 462–468 (2005). Shows the efficacy of the combination of statin and fenofibrate in improving the lipoprotein profile of patients with atherogenic dyslipidaemia.

Keech, A. et al. FIELD study investigators. Effects of long-term fenofibrate therapy on cardiovascular events in 9795 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the FIELD study): randomized controlled trial. Lancet 366, 1849–1861 (2005).

Vega, G. L. et al. Effects of adding fenofibrate (200 mg/day) to simvastatin (10 mg/day) in patients with combined hyperlipidemia and metabolic syndrome. Am. J. Cardiol. 91, 956–960 (2003).

Fruchart, J. C., Duriez, P. & Staels, B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α activators regulate genes governing lipoprotein metabolism, vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 10, 245–257 (1999).

Delerive, P. et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor activators inhibit thrombin-induced endothelin-1 production in human vascular endothelial cells by inhibiting the activator protein-1 signaling pathway. Circ. Res. 85, 394–402 (1999).

Marx, N. et al. PPARα activators inhibit tissue factor expression and activity in human monocytes. Circulation 103, 213–219 (2001).

Neve, B. P. et al. PPARα agonists inhibit tissue factor expression in human monocytes and macrophages. Circulation 103, 207–212 (2001).

Tenkanen, L., Manttari, M. & Manninen, V. Some coronary risk factors related to the insulin resistance syndrome and treatment with gemfibrozil: experience from the Helsinki Heart Study. Circulation 92, 1779–1785 (1995).

Rubins, H. B. High-density lipoprotein and coronary heart disease: lessons from recent intervention trials. Prev. Cardiol. 3, 33–39 (2000).

Rubins, H. B. et al. Diabetes, plasma insulin and cardiovascular disease: subgroup analysis from the Department of Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Intervention Trial (VA-HIT). Arch. Intern. Med. 162, 2597–2604 (2002). Reports that gemfibrozil is particularly effective in cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with insulin resistance and diabetes.

Robins, S. J. et al. Veterans Affairs HDL Intervention Trial (VA-HIT). Insulin resistance and cardiovascular events with low HDL cholesterol: the Veterans Affairs HDL Intervention Trial (VA-HIT) Diabetes Care 26, 1513–1517 (2003).

Linsel-Nitschke, P. & Tall, A. R. HDL as a target in the treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nature Rev. Drug Discov. 4, 193–205 (2005).

Bays, H. & Stein, E. A. Pharmacotherapy for dyslipidaemia — current therapies and future agents. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 4, 1901–1938 (2003).

UKPDS Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes. BMJ 317, 703–713 (1998).

UKPDS Study Group. Efficacy of atenolol and captopril in reducing risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes. BMJ 317, 713–720 (1998).

Pollare, T., Lithell, H., Selinus, I. & Berne, C. Sensitivity to insulin during treatment with atenolol and metoprolol: a randomised, double blind study of effects on carbohydrate and lipoprotein metabolism in hypertensive patients. BMJ 248, 1152–1157 (1989).

Lithell, H. O. Effect of antihypertensive drugs on insulin, glucose, and lipid metabolism. Diabetes Care 14, 203–209 (1991).

The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA 28, 2981–2989 (2002).

Chobanian, A. V. et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 Report. JAMA 289, 2560–2572 (2003).

Bakris, G. L. et al. GEMINI Investigators. Metabolic effects of carvedilol vs metoprolol in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 292, 2227–2236 (2004).

Lithell, H. O. Considerations in the treatment of insulin resistance and related disorders with a new sympatholytic agent. J. Hypertens. Suppl. 15, S39–S42 (1997).

Julius, S., Majahalme, S. & Palatini, P. Antihypertensive treatment of patients with diabetes and hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 14, S310–S316 (2001).

Jandeleit-Dahm, K. A., Tikellis, C., Reid, C. M., Johnston, C. I. & Cooper, M. E. Why blockade of the renin–angiotensin system reduces the incidence of new-onset diabetes. J. Hypertens. 23, 463–473 (2005).

Nickenig, G. Should angiotensin II receptor blockers and statins be combined? Circulation 110, 1013–1020 (2004).

Lonn, E. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers in atherosclerosis. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 4, 363–372 (2002).

Staessen, J. A., Wang, J.-G. & Thijs, L. Cardiovascular prevention and blood pressure reduction: a quantitative overview updated until 1 March 2003. J. Hypertens. 21, 1055–1076 (2003).

Turnbull, F. & Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration. Effects of different blood-pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events: results of prospectively-designed overviews of randomised trials. Lancet 362, 1527–1535 (2003).

Ford, E. S., Giles, W. H. & Mokdad, A. H. Increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults. Diabetes Care 27, 2444–2449 (2004).

Calles-Escandon, J., Garcia-Rubi, E., Mirza, S. & Mortensen, A. Type 2 diabetes: one disease, multiple cardiovascular risk factors. Coron. Artery Dis. 10, 23–30 (1999).

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 329, 977–986 (1993).

Nathan, D. M. et al. Intensive diabetes therapy and carotid intima-media thickness in type 1 diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 2294–2303 (2003).

Nathan, D. M. et al. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDIC) Study Research Group. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 2643–2653 (2005).

Stumvoll, M., Nurjhan, N., Perriello, G., Dailey, G. & Gerich, J. E. Metabolic effects of metformin in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 333, 550–554 (1995).

Zhou, G. et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J. Clin. Invest. 108, 1167–1174 (2001).

UKPDS Group. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet 352, 854–865 (1998).

Adler, A. I. et al. Insulin sensitivity at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes is not associated with subsequent cardiovascular disease (UKPDS 67) Diabetic Med. 22, 306–311 (1998).

Jiang, G. et al. Potentiation of insulin signaling in tissues of Zucker obese rats after acute and long-term treatment with PPARg agonists. Diabetes 51, 2412–2419 (2002).

Way, J. M. et al. Comprehensive messenger ribonucleic acid profiling reveals that peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ activation has coordinate effects on gene expression in multiple insulin-sensitive tissues. Endocrinology 142, 1269–1277 (2001).

Staels, B. PPARγ and atherosclerosis. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 21 (Suppl. 1), 13–20 (2005).

Nesto, R. W. et al. Thiazolidinedione use, fluid retention, and congestive heart failure: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association and American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 27, 256–263 (2004).

Smith, S. R. et al. Effect of pioglitazone on body composition and energy expenditure: a randomized controlled trial. Metabolism 54, 24–32 (2005).

Tontonoz, P., Hu, E. & Spiegelman, B. M. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPARγ 2, a lipid- activated transcription factor. Cell 79, 1147–1156 (1994).

Saladin, R. et al. Differential regulation of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ 1 (PPARγ1) and PPARγ2 messenger RNA expression in the early stages of adipogenesis Cell Growth Differ. 10, 43–48 (1999).

Fajas, L., Debril, M. B. & Auwerx, J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ: from adipogenesis to carcinogenesis. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 27, 1–9 (2001).

Miles, P. D. G., Barak, Y., He, W., Evans, R. M. & Olefsky, J. M. Improved insulin-sensitivity in mice heterozygous for PPAR. J. Clin. Invest. 105, 287–292 (2000).

Rocchi, S. et al. A unique PPARγ ligand with potent insulin-sensitizing yet weak adipogenic activity. Mol. Cell. 8, 737–747 (2001).

Wang, Y. et al. A synthetic triterpenoid, 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-,9-dien-28-oic acid (CDDO), is a ligand for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. Mol. Endocrinol. 14, 1550–1556 (2000).

Cabrero, A., Laguna, J. C. & Vazquez, M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and the control of inflammation. Curr. Drug Targets Inflamm. Allergy 1, 243 –248 (2002).

Haffner, S. M. et al. Effect of rosiglitazone treatment on nontraditional markers of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 106, 679–684 (2002).

Calnek, D. S., Mazzella, L., Roser, S., Roman, J. & Hart, C. M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligands increase release of nitric oxide from endothelial cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23, 52–57 (2003).

Goya, K. et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α agonists increase nitric oxide synthase expression in vascular endothelial cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 658–663 (2004).

Dubey, R. K., Zhang, H. Y., Reddy, S. R., Boegehold, M. A. & Kotchen, T. A. Pioglitazone attenuates hypertension and inhibits growth of renal arteriolar smooth muscle in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 265, R726–R732 (1993).

Law, R. E. et al. Troglitazone inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell growth and intimal hyperplasia. J. Clin. Invest. 98, 1897–1905 (1996).

de Dios, S. T. et al. Inhibitory activity of clinical thiazolidinedione peroxisome proliferator activating receptor-γ ligands toward internal mammary artery, radial artery, and saphenous vein smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circulation 107, 2548–2550 (2003).

Dormandy, J. A. et al. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 366, 1279–1289 (2005). Pioglitazone therapy in patients with diabetes shows a trend towards reduction in cardiovascular events.

Devasthale, P. V. et al. Design and synthesis of N-[(4-methoxyphenoxy)carbonyl]-N-[[4-[2-(5-methyl-2-phenyl-4-oxazolyl)ethoxy]phenyl]methyl]glycine [Muraglitazar/BMS-298585], a novel peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α/γ dual agonist with efficacious glucose and lipid-lowering activities. J. Med. Chem. 48, 2248–2250 (2005).

Reifel-Miller, A. et al. A peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α/γ dual agonist with a unique in vitro profile and potent glucose and lipid effects in rodent models of type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia. Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 593–605 (2005).

Shi, G. Q. Design and synthesis of α-aryloxyphenylacetic acid derivatives: a novel class of PPARα/γ dual agonists with potent antihyperglycemic and lipid modulating activity. J. Med. Chem. 48, 4457–4468 (2005).

Nissen, S. E., Wolski, K. & Topol, E. J. Effect of muraglitazar on death and major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 294, 2581–2586 (2005).

Peters, J. M. et al. Growth, adipose, brain, and skin alterations resulting from targeted disruption of the mouse peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 5119–5128 (2000).

Barak, Y. et al. Effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor d on placentation, adiposity, and colorectal cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 303–308 (2002).

Oliver, W. R. et al. A selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor d agonist promotes reverse cholesterol transport. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5306–5311 (2001).

Evans, R. M., Barish, G. D. & Wang, Y. X. PPARs and the complex journey to obesity. Nature Med. 10, 355–361 (2004).

Wang, Y.-X. et al. Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor d activates fat metabolism to prevent obesity. Cell 113, 159–170 (2003).

Muoio, D. M. et al. Fatty acid homeostasis and induction of lipid regulatory genes in skeletal muscles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)α knock-out mice. Evidence for compensatory regulation by PPAR. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 26089–26097 (2002).

Dressel, U. et al. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/d agonist, GW501516, regulates the expression of genes involved in lipid catabolism and energy uncoupling in skeletal muscle cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 17, 2477–2493 (2003).

Luquet, S. et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-d controls muscle development and oxidative capability. FASEB J. 17, 2299–2301 (2003).

Tanaka, T. et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β induces fatty acid β-oxidation in skeletal muscle and attenuates metabolic syndrome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 15924–15929 (2003).

Kurtz, T. W. & Pravenec, M. Antidiabetic mechanisms of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists: beyond the renin-angiotensin system. J. Hypertens. 22, 2253–2261 (2004).

The Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Follow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 26, 3160–3167 (2003).

Knowler, W. C. et al. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 393–403 (2002). Shows that aggressive lifestyle intervention reduces conversion of pre-diabetes to diabetes. Metformin therapy also reduces the rate of conversion.

Haffner, S. M. The prediabetic problem: development of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and related abnormalities. Diabetes Complications 11, 69–76 (1997).

Alexander, C. M., Landsman, P. B., Teutsch, S. M. & Haffner, S. M. Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III); National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP). NCEP-defined metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and prevalence of coronary heart disease among NHANES III participants age 50 years and older. Diabetes 52, 1210–1214 (2003).

Knowler, W. C. et al. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Prevention of type 2 diabetes with troglitazone in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes 54, 1150–1156 (2005).

Ruderman, N. & Prentki, M. AMP kinase and malonyl-CoA: targets for therapy of the metabolic syndrome. Nature Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 340–351 (2004).

Paterson, J. M. et al. Metabolic syndrome without obesity: hepatic overexpression of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 7088–7093 (2004).

De Pergola, G. & Pannacciulli, N. Coagulation and fibrinolysis abnormalities in obesity. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 25, 899–904 (2002).

Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ 324, 71–86 (2002). Antiplatelet therapy reduces risk for myocardial infarction and stroke in high-risk patients.

Pearson, T. A. et al. AHA Guidelines for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: 2002 Update: Consensus Panel Guide to Comprehensive Risk Reduction for Adult Patients Without Coronary or Other Atherosclerotic Vascular Diseases. American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee. Circulation 106, 388–391 (2002).

Eidelman, R. S., Hebert, P. R., Weisman, S. M. & Hennekens, C. H. An update on aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 163, 2006–2010 (2003).

Ridker, P. M., Wilson, P. W. & Grundy, S. M. Should C-reactive protein be added to metabolic syndrome and to assessment of global cardiovascular risk? Circulation 109, 2818–2825 (2004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

During the past 5 years, S.M.G. has been an investigator on research grants awarded to the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, USA, from Merck, Abbott and Kos Pharmaceuticals. He has also served as a consultant for Merck, Merck Schering Plough, Kos, Abbott, Fournier, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sankyo, AstraZeneca and Sanofi-Aventis.

Related links

Glossary

- Atherogenic dyslipidaemia

-

Atherogenic dyslipidaemia consists of elevations of lipoproteins containing apolipoprotein B (apo B), which include very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), elevations of VLDL triglycerides (and VLDL remnants), increased small LDL particles, and low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL).

- Adiponectin

-

A product of adipose tissue shown to reduce systemic insulin resistance.

- Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system

-

(RAAS). The renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system is a key regulator of blood pressure. It involves the enzymes renin and angiotensin-converting enzyme, which are part of a pathway that converts angiotensinogen to angiotensin II. This acts on the angiotensin II type 1 receptor, leading to various effects that influence blood pressure, including aldosterone release.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grundy, S. Drug therapy of the metabolic syndrome: minimizing the emerging crisis in polypharmacy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 5, 295–309 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd2005

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd2005

This article is cited by

-

Apolipoprotein E polymorphisms contribute to statin response in Chinese ASCVD patients with dyslipidemia

Lipids in Health and Disease (2019)

-

A network-based approach to identify deregulated pathways and drug effects in metabolic syndrome

Nature Communications (2019)

-

Marine microalgae bioengineered Schizochytrium sp. meal hydrolysates inhibits acute inflammation

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

A novel dual PPAR-γ agonist/sEH inhibitor treats diabetic complications in a rat model of type 2 diabetes

Diabetologia (2018)

-

Loss of the E3 ubiquitin ligase MKRN1 represses diet-induced metabolic syndrome through AMPK activation

Nature Communications (2018)