Abstract

The amygdala reveals enhanced reactivity to fearful eye whites, even when they are backwardly masked by a neutral face and therefore processed with limited visual awareness. In our fMRI study, we investigated whether this effect is indeed associated with fear detection within the eyes of the neutral face mask, or more generally, with reactivity to any salient increase in eye white area. In addition, we examined whether a single dose of intranasal oxytocin would modulate amygdala responses to masked fearful eye whites via a double-blind, placebo-controlled pharmacological protocol. We found that increased amygdala responses to salient changes within a face’s eye region occurred specifically for masked fearful eyes but not for similar increases in white area as induced by nonsocial control stimuli. Administration of oxytocin attenuated amygdala responses to masked fearful eye whites. Our results suggest that the amygdala is particularly tuned to potential threat signals from the eye region. The dampening effects of oxytocin on early amygdala reactivity may reflect reduced vigilance for facial threat cues at a preconscious level. Future studies may investigate whether this early modulation accounts for the beneficial effects of oxytocin on social cognition in anxiety-related disorders, as suggested by previous studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The eye region on a face conveys information that is crucial for several aspects of social cognition, including emotion discrimination and identity recognition. Evidence from eye movement studies suggests that the eye is the facial feature that is attended to first and longest during face processing (Scheller et al, 2012). The neuropeptide oxytocin plays a crucial role in regulating mammalian social cognition and behavior (Heinrichs et al, 2009; Meyer-Lindenberg et al, 2011) and it seems to particularly influence the processing of information from the eye region on faces. For example, the intranasal administration of oxytocin was found to improve mental state attribution based on subtle cues from the eye region (Domes et al, 2007b) and to facilitate attentional shifts following gaze cues in emotional faces (Tollenaar et al, 2013). Evidence from eye tracking studies points to a valence-dependent modulation of eye gazing behavior by oxytocin with increased orientation to the eye region on neutral and positive faces (Domes et al, 2013b; Gamer et al, 2010; Guastella et al, 2008), but decreased attentional capture by threatening eye cues (Domes et al, 2013b). Notably, oxytocin’s effects on both facial emotion processing and eye gazing behavior seem to be mediated via the amygdala (Gamer et al, 2010; for a recent review, see Kanat et al, 2014) and to occur very early during stimulus perception (Kanat et al, 2015; Schulze et al, 2011). In a recent study, we showed that intranasal oxytocin specifically reduces amygdala responses and its functional coupling with visual cortex areas when attending to cues from the eye region signaling social threat even when awareness of these cues is largely restricted (Kanat et al, 2015).

The eyes are particularly important in fear recognition (Adolphs et al, 2005; Scheller et al, 2012). A study using intracerebral electrophysiological recordings demonstrated that the amygdala preferentially responds to the eye region as compared with whole faces, and that this effect is most pronounced in conjunction with fearful eyes (Meletti et al, 2012). Evidence from imaging studies further substantiates the amygdala’s critical role in processing fear signals conveyed by the eyes (Morris et al, 2002) and in attentional orienting to fearful eyes (Gamer and Buchel, 2009). Sections of wide-open, fearful eyes were found to elicit stronger responses in the left amygdala than gaze shifts of neutral eyes, despite a similar increase in eye white area (Hardee et al, 2008). Together, these results suggest that the amygdala is specifically tuned to salient eye signals associated with fear.

The amygdala reveals increased responses to fearful faces even when these are immediately masked by another stimulus and thereby processed without conscious awareness (Liddell et al, 2005; Whalen et al, 1998). Results from another study suggest that the amygdala’s enhanced reactivity to masked fearful expressions relies largely on the increase in the white scleral field within fearful eyes (Whalen et al, 2004). However, amygdala responses to masked fearful expressions have been shown to rely on an interaction between emotional and masking stimuli (Kim et al, 2010). Correspondingly, the enhanced amygdala response to fearful eye whites in backward masking paradigms was found to disappear when either the position of the eye stimuli was changed or when the neutral face mask was replaced by another masking stimulus (Straube et al, 2010), suggesting that the amygdala mainly responds to salient events within the eye region of the masking stimulus that are potentially associated with fear. Whether this response is indeed associated with fear detection or whether the amygdala reacts more generally to any salient increase in eye white area has not been investigated yet.

We addressed this question with a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study that assessed brain responses to masked fearful and happy eye whites. Based on the above-mentioned studies, we assumed that the amygdala responds more strongly to eye whites of masked fearful than to happy expressions. We further predicted that the same effect would not be observed by similar increases in the white area in nonsocial control stimuli. Furthermore, we examined whether a single dose of intranasal oxytocin would modulate responses of the amygdala and associated brain structures to masked fearful eye whites by means of a double-blind, placebo-controlled pharmacological protocol. As previous studies reported dampening oxytocin effects on amygdala reactivity to facial threat in men (Domes et al, 2007a; Kanat et al, 2015; Kirsch et al, 2005; Petrovic et al, 2008), we expected decreased amygdala responses to fearful eye whites following oxytocin as compared with placebo administration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and Experimental Procedure

A total of 50 healthy male participants were recruited at the University of Freiburg to participate in a study on ‘oxytocin and face processing’. All participants were right-handed nonsmokers and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. They reported no previous or current medical illness or psychiatric disorder, with the latter validated using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Individuals were excluded in case of regular medication use or if they fulfilled MR-specific contraindications (eg, cardiac pacemaker, metal in body). Women were excluded from participation because of known sex differences regarding emotional reactivity as well as cycle-dependent hormonal variability. All participants gave their written informed consent and received monetary reimbursement following participation. They were asked to abstain from caffeine, alcohol, and medication use on the day of testing, and were instructed not to eat or drink anything (except water) 2 h before the experiment. The study took place in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics commission.

On the testing day, participants filled out questionnaires and received thorough instruction on the testing procedure and experiment. To become familiar with the task, they completed eight blocks of testing trials on a notebook. For another experimental task that preceded the task reported here, they were equipped with an electrode cap for facial EMG measurements. The electrode cap was not removed for the eye white task in order to save scanning time and to ensure that oxytocin levels remained high enough. Notably, as the first experimental task tested for oxytocin effects on facial mimicry behavior, it did not interfere with the research question being addressed in this study. Following electrode placement, participants were randomly assigned to receive OT (Syntocinon-Spray, Novartis) or placebo (containing all ingredients except the neuropeptide) via a nasal spray in a double-blind manner. Under the experimenter’s supervision, they self-administered 3 puffs into each nostril amounting to a total dosage of 24 IU in the oxytocin condition. Administration was completed ∼55 min before the experiment started. To control for potential oxytocin effects on mood, wakefulness, and calmness, participants completed a multidimensional questionnaire (Steyer et al, 1997) before substance administration and before entering the scanner. After the scanning session, participants were asked to describe the experimental stimuli and to report any perceived peculiarity throughout the experimental task. They were then debriefed about the nature of the experiment and shown some of the masked target stimuli. In case of self-reported awareness of these stimuli, subjects were excluded from data analysis.

Experimental Task and Stimuli

Before beginning the experiment, participants were told that they would see faces briefly appearing on the screen and that their task was to identify the gender of the last face within each block by pressing one of two mouse buttons. This cover story was used to maintain a high level of attention throughout the experimental blocks. As oxytocin is known to alter amygdala-mediated eye gazing behavior (Domes et al, 2013b; Guastella et al, 2008), participants were explicitly instructed to focus on the eye region on faces in order to rule out substance-induced differences in visual attention as a potential confounder. Participants then viewed blocks of masked fearful or happy eyes or nonsocial control stimuli that had been matched for the amount of white area. Control stimuli were included to rule out the possibility that the amygdala reacts to salient changes within the eye region of the masking stimulus irrespective of emotional significance.

All stimuli were based on pictures of seven male and seven female Caucasian faces taken from the NimStim Face Stimulus Set (http://www.macbrain.org/resources.htm). For each identity, pictures depicting a neutral, fearful, and happy expression were selected and converted to a black-and-white color scale. To create the neutral masking stimuli, hair and nonfacial parts were removed. To create the emotional stimuli, the eye region on happy and fearful faces was cut-out and spurs of gray shadows removed from the sclera. Control stimuli consisted of a scrambled version of these fearful or happy eyes and were therefore characterized by a similar amount of white area as the eye stimuli. The position of the eye and control stimuli was carefully matched to the neutral face of the masking stimulus. Images were projected on a semiopaque screen (resolution: 1280 × 1024 pixels) made visible via a mirror mounted on the head coil.

In total, 12 experimental blocks were shown (three blocks per experimental condition) that alternated with rest blocks in which subjects viewed a red crosshair. Blocks were presented within a single run lasting ∼14 min. Each experimental block consisted of 56 trials. Both blocks and trials within a block were presented in pseudorandomized order to rule out that the same experimental condition or same facial identity could be presented back to back. Each trial began with the target picture (33 ms) displaying happy or fearful eyes or the corresponding scrambled eye components (see Figure 1). The target picture was immediately masked by a neutral face (183 ms) of the same identity. Between trials, a black screen appeared for 300 ms. Regarding the target stimuli, we decided on a duration longer than that used in previous studies on processing fearful eye whites to allow for more variance in both substance groups. Stimulus presentation was controlled by Presentation 14 (www.neurobs.com).

(a) Example stimuli for the four experimental conditions. (b) Block structure and duration of target and masking stimuli as exemplified for the fearful eyes condition.

Imaging Parameters and Data Analysis

Imaging was performed on a Siemens TIM Trio 3T system (Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) with a 12-channel head coil at the University Hospital Freiburg. Head motion was minimized using fasteners and additional foam paddings. A total of 408 functional images were acquired in a single session with a T2*-weighted gradient-echo planar sequence using BOLD contrast (TR=2.04 s; TE=28 ms; flip angle=70°; field of view=224 mm, voxel size=3.0 × 3.0 × 3.5, 1 mm gap between slices). Each brain volume comprised 34 oblique axial slices measured in descending order and covering the whole brain except lower parts of the cerebellum. To establish magnetization equilibrium, the first five volumes of each functional time series were discarded from subsequent analyses. In addition to functional scans, an anatomical image was acquired for each participant with a 3D MPRAGE sequence (TR=2.2 s; TE=2.15 ms; flip angle=12°; 1 × 1 × 1 mm isotropic resolution) and later coregistered with the functional data.

Functional images were corrected from motion and distortion artifacts during scanning by means of a point spread function mapping approach (Zaitsev et al, 2004). Following visual inspection of artifacts related to fast motion, data were preprocessed and analyzed in SPM8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). Images were spatially normalized to MNI space based on segmentation parameters from anatomical scans, and smoothed using a 9 mm FWHM (full width at half maximum) Gaussian kernel. On the single-subject level, experimental runs of each condition were modeled as box-car functions with a canonical hemodynamic response function. To remove residual movement-related variance, movement parameters estimated from raw functional images were included as potential confounds. As we were mainly interested in effects within the amygdala, a structure known to display substantial changes in activation following stimulus repetition (Breiter et al, 1996), we additionally modeled exponential decay regressors for each experimental block. Low-frequency noise within the time series was removed by applying a 128-s high-pass filter.

For each individual and experimental condition, regression coefficients were estimated and forwarded to a full-factorial random effects analysis on the group level. Within this analysis, we tested for effects of substance group (oxytocin, placebo), emotion (happy, fearful), and stimulus type (eyes, control) on BOLD activity. As the bilateral amygdalae represented our main regions of interest (ROIs), we applied a small volume correction in these areas via anatomical masks derived from the WFU PickAtlas (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al, 2002). To retrace the contribution of distinct amygdala subregions to observed effects, we applied maximum probabilistic anatomical maps in a second step using the anatomy toolbox integrated in SPM (Eickhoff et al, 2005). The significance threshold was set to p<0.05, corrected for the number of voxels within the ROI. We also conducted an exploratory whole-brain analysis with a liberal threshold of p<0.001 and minimum cluster size of 10 contiguous voxels.

RESULTS

In the placebo group, we had to exclude four subjects because of subjective awareness of the target stimuli (n=1), anatomical abnormalities (n=1), or severe and uncorrectable motion artifacts (n=2). In the oxytocin group, motion artifacts led to the exclusion of two participants. Our remaining sample therefore comprised 43 subjects (PL: n=21; OT: n=22). Substance groups did not differ in age (mean age±SD: PL: 23.9±2.74, OT: 24.32±3.43; T41=−0.485, p=0.630), potentially relevant personality traits such as anxiety (STAI: PL: 37.19±8.94, OT: 35.19±10.83; T40=0.653, p=0.518), or autistic traits (AQ: PL: 16.00±6.60, OT: 15.95±5.07; T40=0.026, p=0.979).

Analyses within the Placebo Group

We first conducted separate voxel-wise analyses within the left and right amygdala under placebo conditions. This procedure revealed voxels within both amygdalae that showed increased responses to fearful as compared with happy target cues irrespective of stimulus type, that is, that were generally activated by salient changes within the eye region on the mask (left: k=8; x, y, z: −19, −7, −17; T=2.88; pSVC=0.029; right: k=17; x, y, z: 27, −7, −14; T=2.84; pSVC=0.035). We next tested for differential amygdala reactivity to fearful eye whites as compared with control stimuli using the interaction contrast EyesFear>Happy>ControlFear>Happy. There were no voxels displaying a significant interaction between the degree of white area and the stimulus type (left: pSVC>0.05 for all voxels). However, testing for both stimulus types separately revealed significant reactivity to fearful as compared with happy targets only in the eye condition (left: k=10; x, y, z: −22, −7, −14; T=2.76; pSVC=0.039; right: k=41; x, y, z: 34, 0, −29; T=3.31; pSVC=0.010), whereas no voxels showed increased responses to fearful targets in the control condition (left and right amygdala: pSVC>0.05 for all voxels; see Figure 2).

Effects of salient changes in the eye region on the neutral face mask within the right amygdala ROI for both stimulus type conditions. (a) Fearful eyes significantly increased activation within the right amygdala (x, y, and z: 34, 0, −29; T=3.31; pSVC=0.010), whereas similar effects were absent in the control condition (pSVC>0.05). For illustration purposes, the SPMs are displayed at an uncorrected threshold of p<0.05. (b) Percent signal change within the right amygdala peak voxel for masked ‘fearful’ and ‘happy’ target stimuli in the eyes and control condition.

The additional exploratory whole-brain analysis revealed a significant modulation of brain activity by salient changes within the eye region on the neutral face mask beyond the predefined amygdala ROI (see Supplementary Table S1). Several brain areas, including the right pulvinar (k=90; x, y, z: 13,− 28, 4; T=4.09; puncorr<0.001), left anterior cingulate cortex (k=13; x, y, z: −8, 49, −2; T=3.56; puncorr<0.001), and right medial orbitofrontal cortex (k=21; x, y, z: 3, 67, −2; T=4.25; puncorr<0.001) responded to fearful targets irrespective of stimulus type (Fearful>Happy; Supplementary Table S1). However, within separate analyses of the two stimulus types, the pulvinar was the only region that specifically responded to the eye condition (k=135; x, y, z: 13, −32, 4; T=4.31; puncorr<0.001), whereas significant effects on the same statistical threshold were absent in the control condition (see Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S1). Notably, across the whole brain, no voxels displayed a significant interaction between stimulus type and the amount of white area. In sum, analyses within the placebo group revealed significant modulation by salient changes within the eye region on the masking stimulus within the right amygdala and right pulvinar that seemed specific to eye stimuli.

Effects of salient changes in the eye region of the neutral face mask on pulvinar activity for both stimulus type conditions as revealed by whole-brain analysis. (a) Fearful eyes significantly increased activation of the right pulvinar (whole-brain analysis; x, y, and z: 13, −32, 4; T=4.31; puncorr<0.001), whereas similar effects were absent in the control condition (puncorr>0.001). (b) Percent signal change within the right pulvinar peak voxel for masked ‘fearful’ and ‘happy’ target stimuli in the eyes and control condition.

Modulation of Brain Responses by Intranasal Oxytocin

We next tested for brain-activity modulation via intranasal oxytocin with specific focus on oxytocin effects on responses within the bilateral amygdalae and right pulvinar as regions of interest. Within the amygdalae, oxytocin administration had no effect during the processing of fearful as compared with happy control stimuli (pSVC>0.05 for all voxels). Conversely, oxytocin significantly reduced right amygdala responses to fearful as compared with happy stimuli in the eye condition (PlaceboEyes: Fear>Happy>OxytocinEyes: Fear>Happy: k=35; x, y, z: 34, 0, −26; T=2.77; pSVC=0.042; Figure 4). Applying maximum probability maps to the observed oxytocin effect revealed that the majority of significant voxels including the peak voxel were located within the basolateral amygdala, whereas the remaining voxels of the cluster lay within the superficial complex (see Supplementary Figure S1). Analysis within the right pulvinar revealed no significant oxytocin effects on reactivity to either fearful eye whites or fearful control stimuli (pSVC>0.05 for all voxels). However, observed as a trend, oxytocin lowered right pulvinar reactivity to fearful targets irrespective of stimulus type (PlaceboFear>Happy>OxytocinFear>Happy: k=41; x, y, z: 17, −35, 1; T=2.62; pSVC=0.053). In contrast, neither the amygdalae nor right pulvinar displayed an increase in responses to fearful targets following oxytocin administration.

Effects of intranasal oxytocin on reactivity to masked fearful as compared with happy eyes within the right amygdala ROI. (a) Oxytocin significantly reduced right amygdala responses to masked fearful eyes (x, y, and z: 34, 0, −26; T=2.77; pSVC=0.042). For illustration purposes, the SPMs are displayed at an uncorrected threshold of p<0.05. (b) Percent signal change within the right amygdala peak voxel for masked ‘fearful’ and ‘happy’ eye stimuli in the placebo and oxytocin condition.

Results from the subsequent exploratory whole-brain analysis within the oxytocin group are reported in Supplementary Table S2. In addition, we applied differential contrasts that tested for significant effects of oxytocin versus placebo administration (see Supplementary Table S3). These analyses revealed dampening oxytocin effects on brain responses to fearful as compared with happy stimuli across stimulus type conditions within the left anterior cingulate cortex (k=13; x, y, z: −8, 49, −2; T=3.53; puncorr<0.001) and left midtemporal gyrus (k=18; x, y, z: −54, −7, −14; T=3.42; puncorr<0.001). Both regions displayed enhanced reactivity to salient increases in white area within the eye region on the neutral face mask under placebo, whereas this effect disappeared following oxytocin administration (additional clusters are reported in Supplementary Table S3). We observed no significant voxels displaying increased reactivity to salient, that is, ‘fearful’, stimuli under oxytocin as compared with placebo (puncorr>0.001).

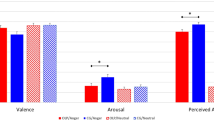

To control for differential changes within subjective state measures following substance administration, we ran a repeated-measures ANOVA on the MBDF subscales. This analysis revealed that oxytocin administration had no differential effect on changes in self-reported wakefulness or mood across the experimental session (substance × time interaction: all F1, 38≤2.7, all p≥0.11; Supplementary Table S4). Regarding self-perceived calmness, the oxytocin group demonstrated higher values than the placebo group despite randomized assignment to substance groups (main effect of substance group: F1, 38=7.19, p=0.011). Entering each participant’s baseline value as a covariate into our group analysis, however, did not change our results’ significance.

DISCUSSION

This study examined whether the increased amygdala response to masked fearful eye whites as observed in previous studies is emotion specific or whether it is solely driven by salient changes within the eye region on the neutral face mask irrespective of emotional meaning. Furthermore, we investigated whether a single dose of intranasal oxytocin would alter neural reactivity to masked fearful eye whites within the amygdala and associated areas. Under placebo conditions, we noted enhanced amygdala reactivity to fearful as compared with happy eye whites masked with a neutral face, thereby replicating previous studies’ results (Straube et al, 2010; Whalen et al, 2004). In addition, we observed the same effect within the pulvinar that is known to be extensively interconnected with the amygdala both anatomically (Tamietto et al, 2012) and functionally (Morris et al, 1999; Troiani et al, 2014). These heightened neural responses occurred despite subjective unawareness of the presented stimuli. Furthermore, they seemed specific to fearful eye whites and not driven solely by increases in luminance as control stimuli (scrambled eye whites) evoked no significant differential responses. Our findings therefore suggest that the amygdala does not generally respond to an increase in white area within the eye region on a face mask. Rather, both the amygdala and pulvinar seem to display a preference for fear-related eye cues before conscious stimulus processing. This underlines the involvement of both structures in preconscious fear processing (Liddell et al, 2005; Morris et al, 2002).

The administration of intranasal oxytocin decreased amygdala responses to masked fearful eye whites. This finding concurs with a recent study’s data showing that oxytocin attenuates amygdala responses to threat cues from the eye region at very early stages of emotion perception (Kanat et al, 2015). In addition, oxytocin reduced the reactivity of the pulvinar, anterior cingulate cortex, and parts of the ventral stream to salient changes within the eye region on the neutral face mask irrespective of emotional meaning. Although all of these structures have previously been implicated in the processing of masked fearful faces (Liddell et al, 2005), our results suggest that a subtle increase in eye white suffices to activate this ‘alarm network’. Within this system, the pulvinar is thought to amplify the processing of salient and emotionally significant stimuli via its widespread connections with visual cortex areas and with the structures involved in salience processing such as the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex (Pessoa and Adolphs, 2010). Beyond this context, the oxytocin effects we observed may reflect an impairment in the early processing of fear-related signals from the eye region by modulatory influences on an emotional salience network (cf. Koch et al, 2014).

Such early oxytocin modulation may underlie its known effects on social attention. For example, there is evidence that oxytocin facilitates attentional disengagement from negative facial expressions (Domes et al, 2013b; Ellenbogen et al, 2012) and enhances the allocation of attentional resources toward positive but not negative social cues (Domes et al, 2013a; Prehn et al, 2013). In addition, decreased neural reactivity to threat cues from the eyes following oxytocin administration may contribute to its prosocial effects when evaluating negative stimuli. For instance, intranasal oxytocin reduces subjective experiences of threat from aversively conditioned facial expressions (Petrovic et al, 2008), increases approach motivation to socially threatening stimuli (Radke et al, 2013), and attenuates affective reactions to social betrayal (Baumgartner et al, 2008).

An early modulation of facial threat perception by oxytocin may be particularly relevant in disorders characterized by hypersensitivity to social threat. For example, social anxiety is associated with increased orientation to facial threat (Mogg et al, 2007; Mogg and Bradley, 2002), enhanced attentional cuing by fearful eye gazes (Fox et al, 2007), and aversion to direct eye gaze (for a recent review, see Schulze et al, 2013). On the neural level, anxious individuals reveal increased amygdala responses to fearful faces (Labuschagne et al, 2010) as well as decreased connectivity between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex regions (Dodhia et al, 2014; Kim et al, 2011). The amygdala’s basolateral complex is known to promote reactivity to fear signals through interaction with the noradrenergic system (Hurlemann et al, 2010). Notably, individual anxiety levels are known to correlate with basolateral amygdala responsiveness to backwardly masked fearful faces (Etkin et al, 2004), and damage to this structure is assumed to induce hypervigilance for threat cues (Terburg et al, 2012).

In our study, increased amygdala responses to masked fearful eye whites were located within the basolateral amygdala, whereas this effect tended to vanish following oxytocin administration, suggesting anxiolytic effects. This result is consistent with the normalizing effects of intranasal oxytocin on both heightened amygdala responses to fearful faces (Labuschagne et al, 2010) and hypoconnectivity between the amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex in social anxiety disorder (Dodhia et al, 2014). Moreover, it bolsters recent evidence from an eye tracking study suggesting that oxytocin may reduce hypervigilance in particular to threat cues from the eye region and associated amygdala reactivity (Bertsch et al, 2013). Our findings suggest that oxytocin decreases reactivity to subtle fear cues from the eye region via inhibitory influences on the basolateral amygdala and, potentially, its coupling with the noradrenergic system. This may serve as a key mechanism by which oxytocin could help to reduce hypervigilance for social threat in anxiety-related disorders.

Taken together, our results support the idea that a network comprising the amygdala, pulvinar, anterior cingulate, and visual cortex regions automatically detects salient changes within the eye region on faces and classifies their emotional relevance before conscious stimulus evaluation. This network’s modulations observed via oxytocin administration may reflect a decrease in the preconscious ascriptions of biological significance to potential threat cues from the eyes. Future studies may investigate whether these modulations account for oxytocin’s positive effects on social attention processes in social anxiety.

Funding and Disclosure

This study was supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation to GD and MH (DFG, Do1312/2-1). The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Adolphs R, Gosselin F, Buchanan TW, Tranel D, Schyns P, Damasio AR (2005). A mechanism for impaired fear recognition after amygdala damage. Nature 433: 68–72.

Baumgartner T, Heinrichs M, Vonlanthen A, Fischbacher U, Fehr E (2008). Oxytocin shapes the neural circuitry of trust and trust adaptation in humans. Neuron 58: 639–650.

Bertsch K, Gamer M, Schmidt B, Schmidinger I, Walther S, Kästel T et al (2013). Oxytocin and reduction of social threat hypersensitivity in women with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 170: 1169–1177.

Breiter HC, Etcoff NL, Whalen PJ, Kennedy WA, Rauch SL, Buckner RL et al (1996). Response and habituation of the human amygdala during visual processing of facial expression. Neuron 17: 875–887.

Dodhia S, Hosanagar A, Fitzgerald DA, Labuschagne I, Wood AG, Nathan PJ et al (2014). Modulation of resting-state amygdala-frontal functional connectivity by oxytocin in generalized social anxiety disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 39: 2061–2069.

Domes G, Heinrichs M, Gläscher J, Büchel C, Braus DF, Herpertz SC (2007a). Oxytocin attenuates amygdala responses to emotional faces regardless of valence. Biol Psychiatry 62: 1187–1190.

Domes G, Heinrichs M, Michel A, Berger C, Herpertz SC (2007b). Oxytocin improves ‘mind-reading’ in humans. Biol Psychiatry 61: 731–733.

Domes G, Sibold M, Schulze L, Lischke A, Herpertz SC, Heinrichs M (2013a). Intranasal oxytocin increases covert attention to positive social cues. Psychol Med 43: 1747–1753.

Domes G, Steiner A, Porges SW, Heinrichs M (2013b). Oxytocin differentially modulates eye gaze to naturalistic social signals of happiness and anger. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38: 1198–1202.

Eickhoff SB, Stephan KE, Mohlberg H, Grefkes C, Fink GR, Amunts K et al (2005). A new SPM toolbox for combining probabilistic cytoarchitectonic maps and functional imaging data. Neuroimage 25: 1325–1335.

Ellenbogen MA, Linnen A-M, Grumet R, Cardoso C, Joober R (2012). The acute effects of intranasal oxytocin on automatic and effortful attentional shifting to emotional faces. Psychophysiology 49: 128–137.

Etkin A, Klemenhagen KC, Dudman JT, Rogan MT, Hen R, Kandel ER et al (2004). Individual differences in trait anxiety predict the response of the basolateral amygdala to unconsciously processed fearful faces. Neuron 44: 1043–1055.

Fox E, Calder AJ, Mathews A, Yiend J (2007). Anxiety and sensitivity to gaze direction in emotionally expressive faces. Emotion 7: 478–486.

Gamer M, Buchel C (2009). Amygdala activation predicts gaze toward fearful eyes. J Neurosci 29: 9123–9126.

Gamer M, Zurowski B, Buchel C (2010). Different amygdala subregions mediate valence-related and attentional effects of oxytocin in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 9400–9405.

Guastella AJ, Mitchell PB, Dadds MR (2008). Oxytocin increases gaze to the eye region of human faces. Biol Psychiatry 63: 3–5.

Hardee JE, Thompson JC, Puce A (2008). The left amygdala knows fear: laterality in the amygdala response to fearful eyes. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 3: 47–54.

Heinrichs M, Dawans B, von, Domes G (2009). Oxytocin, vasopressin, and human social behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol 30: 548–557.

Hurlemann R, Walter H, Rehme AK, Kukolja J, Santoro SC, Schmidt C et al (2010). Human amygdala reactivity is diminished by the β-noradrenergic antagonist propranolol. Psychol Med 40: 1839–1848.

Kanat M, Heinrichs M, Domes G (2014). Oxytocin and the social brain: neural mechanisms and perspectives in human research. Brain Res 1580: 160–171.

Kanat M, Heinrichs M, Schwarzwald R, Domes G (2015). Oxytocin attenuates neural reactivity to masked threat cues from the eyes. Neuropsychopharmacology 40: 287–295.

Kim MJ, Loucks RA, Neta M, Davis FC, Oler JA, Mazzulla EC et al (2010). Behind the mask: the influence of mask-type on amygdala response to fearful faces. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 5: 363–368.

Kim MJ, Loucks RA, Palmer AL, Brown AC, Solomon KM, Marchante AN et al (2011). The structural and functional connectivity of the amygdala: From normal emotion to pathological anxiety. Behav Brain Res 223: 403–410.

Kirsch P, Esslinger C, Chen Q, Mier D, Lis S, Siddhanti S et al (2005). Oxytocin modulates neural circuitry for social cognition and fear in humans. J Neurosci 25: 11489–11493.

Koch SBJ, Zuiden M, van, Nawijn L, Frijling JL, Veltman DJ, Olff M (2014). Intranasal oxytocin as strategy for medication-enhanced psychotherapy of PTSD: Salience processing and fear inhibition processes. Psychoneuroendocrinology 40: 242–256.

Labuschagne I, Phan KL, Wood A, Angstadt M, Chua P, Heinrichs M et al (2010). Oxytocin attenuates amygdala reactivity to fear in generalized social anxiety disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 2403–2413.

Liddell BJ, Brown KJ, Kemp AH, Barton MJ, Das P, Peduto A et al (2005). A direct brainstem–amygdala–cortical ‘alarm’ system for subliminal signals of fear. Neuroimage 24: 235–243.

Meletti S, Cantalupo G, Benuzzi F, Mai R, Tassi L, Gasparini E et al (2012). Fear and happiness in the eyes: an intra-cerebral event-related potential study from the human amygdala. Neuropsychologia 50: 44–54.

Meyer-Lindenberg A, Domes G, Kirsch P, Heinrichs M (2011). Oxytocin and vasopressin in the human brain: social neuropeptides for translational medicine. Nat Rev Neurosci 12: 524–538.

Mogg K, Bradley BP (2002). Selective orienting of attention to masked threat faces in social anxiety. Behav Res Ther 40: 1403–1414.

Mogg K, Garner M, Bradley BP (2007). Anxiety and orienting of gaze to angry and fearful faces. Biol Psychol 76: 163–169.

Morris JS, deBonis M, Dolan RJ (2002). Human amygdala responses to fearful eyes. Neuroimage 17: 214–222.

Morris JS, Öhman A, Dolan RJ (1999). A subcortical pathway to the right amygdala mediating ‘unseen’ fear. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96: 1680–1685.

Pessoa L, Adolphs R (2010). Emotion processing and the amygdala: from a ‘low road’ to ‘many roads’ of evaluating biological significance. Nat Rev Neurosci 11: 773–783.

Petrovic P, Kalisch R, Singer T, Dolan RJ (2008). Oxytocin attenuates affective evaluations of conditioned faces and amygdala activity. J Neurosci 28: 6607–6615.

Prehn K, Kazzer P, Lischke A, Heinrichs M, Herpertz SC, Domes G (2013). Effects of intranasal oxytocin on pupil dilation indicate increased salience of socioaffective stimuli. Psychophysiology 50: 528–537.

Radke S, Roelofs K, de Bruijn ERA (2013). Acting on anger: social anxiety modulates approach-avoidance tendencies after oxytocin administration. Psychol Sci 24: 1573–1578.

Scheller E, Büchel C, Gamer M (2012). Diagnostic features of emotional expressions are processed preferentially. PLoS One 7: e41792.

Schulze L, Lischke A, Greif J, Herpertz SC, Heinrichs M, Domes G (2011). Oxytocin increases recognition of masked emotional faces. Psychoneuroendocrinology 36: 1378–1382.

Schulze L, Renneberg B, Lobmaier JS (2013). Gaze perception in social anxiety and social anxiety disorder. Front Hum Neurosci 7: 872.

Steyer R, Schwenkmezger P, Notz P, Eid M (1997) Der Mehrdimensionale Befindlichkeitsfragebogen MDBF [Multidimensional Mood Questionnaire]. Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany.

Straube T, Dietrich C, Mothes-Lasch M, Mentzel H-J, Miltner WHR (2010). The volatility of the amygdala response to masked fearful eyes. Hum Brain Mapp 31: 1601–1608.

Tamietto M, Pullens P, de Gelder B, Weiskrantz L, Goebel R (2012). Subcortical connections to human amygdala and changes following destruction of the visual cortex. Curr Biol 22: 1449–1455.

Terburg D, Morgan BE, Montoya ER, Hooge IT, Thornton HB, Hariri AR et al (2012). Hypervigilance for fear after basolateral amygdala damage in humans. Transl Psychiatry 2: e115.

Tollenaar MS, Chatzimanoli M, van der Wee NJA, Putman P (2013). Enhanced orienting of attention in response to emotional gaze cues after oxytocin administration in healthy young men. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38: 1797–1802.

Troiani V, Price ET, Schultz RT (2014). Unseen fearful faces promote amygdala guidance of attention. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 9: 133–140.

Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N et al (2002). Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage 15: 273–289.

Whalen PJ, Kagan J, Cook RG, Davis FC, Kim H, Polis S et al (2004). Human amygdala responsivity to masked fearful eye whites. Science 306: 2061–2061.

Whalen PJ, Rauch SL, Etcoff NL, McInerney SC, Lee MB, Jenike MA (1998). Masked presentations of emotional facial expressions modulate amygdala activity without explicit knowledge. J Neurosci 18: 411–418.

Zaitsev M, Hennig J, Speck O (2004). Point spread function mapping with parallel imaging techniques and high acceleration factors: fast, robust, and flexible method for echo-planar imaging distortion correction. Magn Reson Med 52: 1156–1166.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to MR Hansjörg Mast, for his help in carrying out the MR measurements. We also thank Franziska Niemeyer and Rudolf Siegel for assistance with data collection, Sarah Bütof for help with the clinical interviews, and Valentina Colonnello and Elisa Scheller for valuable discussions about the manuscript. Furthermore, we extend our gratitude to all the participants who took part in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kanat, M., Heinrichs, M., Mader, I. et al. Oxytocin Modulates Amygdala Reactivity to Masked Fearful Eyes. Neuropsychopharmacol 40, 2632–2638 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.111

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.111

This article is cited by

-

Non-conscious processing of fear faces: a function of the implicit self-concept of anxiety

BMC Neuroscience (2023)

-

Effects of exogenous oxytocin and estradiol on resting-state functional connectivity in women and men

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

EmBody/EmFace as a new open tool to assess emotion recognition from body and face expressions

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Kinetics of oxytocin effects on amygdala and striatal reactivity vary between women and men

Neuropsychopharmacology (2020)

-

Oxytocin biases eye-gaze to dynamic and static social images and the eyes of fearful faces: associations with trait autism

Translational Psychiatry (2020)