Abstract

Background:

Hundreds of thousands of incidental pulmonary nodules are detected annually in the United States, and this number will increase with the implementation of lung cancer screening. The lengthy period for active pulmonary nodule surveillance, often several years, is unique among cancer regimens. The psychosocial impact of longitudinal incidental nodule follow-up, however, has not been described.

Aims:

We sought to evaluate the psychosocial impact of longitudinal follow-up of incidental nodule detection on patients.

Methods:

Veterans who participated in our previous study had yearly follow-up qualitative interviews coinciding with repeat chest imaging. We used conventional content analysis to explore their knowledge of nodules and the follow-up plan, and their distress.

Results:

Seventeen and six veterans completed the year one and year two interviews, respectively. Over time, most patients continued to have inadequate knowledge of pulmonary nodules and the nodule follow-up plan. They desired and appreciated more information directly from their primary care provider, particularly about their lung cancer risk. Distress diminished over time for most patients, but it increased around the time of follow-up imaging for some, and a small number reported severe distress.

Conclusions:

In settings in which pulmonary nodules are commonly detected, including lung cancer screening programmes, resources to optimise patient-centred communication strategies that improve patients’ knowledge and reduce distress should be developed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the United States, hundreds of thousands of incidental pulmonary nodules are detected annually during chest imaging.1–3 This number is expected to increase substantially because lung cancer screening is now recommended by the United States Preventative Services Task Force4 for patients with elevated risk, defined as adults aged 55–80 years who have a 30-pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years, on the basis of the results of the National Lung Screening Trial.5 Once detected, experts recommend that patients with nodules undergo serial follow-up imaging, often for 2 years.6,7 Researchers are just beginning to explore potential psychological harms of nodule detection8 and how these harms may be mitigated.

Patients experience significant distress after incidental nodule detection.9–11 A systematic review of lung cancer screening trials, mostly from Europe, found that false positive screening results were often associated with short-term increases in distress, which returned to baseline levels over time.8 Little is known about how patients’ emotional responses, knowledge of an incidental pulmonary nodule and the follow-up plan change over time, as well as the impact of distress. In other settings not related to pulmonary nodule detection, distress impedes smoking cessation and contributes to re-initiation.12,13 Among patients undergoing breast and colorectal cancer screening, distress interferes with adherence to subsequent medical care and screening recommendations.14–18

Provider communication strategies that help mitigate patients’ distress and improve comprehension are important, as recommended by a bioethics commission on incidental findings.19 Learning how these strategies satisfy patients’ expectations, preferences and desires is important, as they are essential components of quality care.20,21 We previously reported the results of a qualitative analysis of veterans’ knowledge and distress of initial pulmonary nodule detection.22 The present study extends that work through follow-up interviews over 2 years to explore patients’ understanding of the pulmonary nodule and its evaluation process, their emotional reactions and their views about provider communication regarding nodule detection. Exploring patients’ longitudinal experiences is essential given the potential impact on adherence to medical care, smoking cessation and their well-being over time. In addition, the unique length of follow-up recommended for pulmonary nodules, compared with other cancer screening programmes, makes longitudinal results particularly salient.

Materials and methods

A follow-up qualitative study was conducted at the VA Portland Health Care System, which is an academically affiliated hospital with outlying clinics, among 17 patients with an incidentally detected (not from screening) pulmonary nodule. At the VA Portland Health Care System, radiology images with pulmonary nodules are electronically flagged.1 Among patients with small nodules, primary care providers (PCPs) are usually responsible for notification and determination of the timing of subsequent evaluations without guidance from pulmonologists. PCPs included were physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Asymptomatic patients with a plan to obtain non-urgent follow-up imaging were eligible. We excluded patients who scored <17/30 on the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination,23 who resided in skilled nursing care facilities and who were diagnosed with psychotic or cognitive disorders, a terminal illness or severe hearing impairment. After approval from respective patients’ PCPs and mental health clinician (if relevant), we contacted the patient by mail to invite participation. The Internal Review Board of the VA Portland Health Care System approved this study and all the patients provided written informed consent.

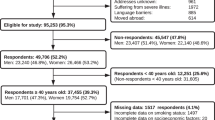

Participants were interviewed after first and second annual follow-up chest CT scans for a maximum of two follow-up interviews or ~2 years. Interviews stopped when nodule follow-up imaging was no longer recommended. As a result, 17 of the initial 19 participants were interviewed after their first annual follow-up CT scan, and 6 of these were interviewed after their second annual follow-up scan. After the baseline interview, one patient died from an unrelated medical problem and one declined further participation. None of the participants missed imaging appointments or were lost to follow-up. The interview guide (Supplementary File) was organised around the core domains of the patient-centred communication (PCC) model, which emphasises the importance of the relationship between communication and health. Key domains of effective PCC include the following: Information Exchange, Patient as Person, Sharing Power and Responsibility, Therapeutic Alliance and Provider as Person.24 Participants were interviewed by an experienced qualitative interviewer (CGS, a pulmonologist), and none of the participants had a previous relationship with the interviewer. Interviews were digitally recorded. We recorded self-reported demographic and smoking characteristics; nodule characteristics were based on imaging reports and medical records review, not independent review of the images. Participants were assigned study letters, and numbers were used to indicate from which visit quotes were obtained: V2=visit two, V3=visit three.

Analysis

We used conventional content analysis, which allows comprehensive description of a patient’s experience in everyday language with little dependence on interpretation or theorisation.25,26 Data were reviewed and analysed in two separate but comparable phases. Phase 1 included the baseline patient interviews only22 and phase 2 included all follow-up interviews. The code structure was developed inductively27 using the PCC model as an organising framework.24 The phase 2 analysis included a comparison of codes between baseline and follow-up interviews.26 Follow-up interviews were reviewed by CGS, DRS and SEG, who as a group reviewed two completed patient transcripts to assess congruence with the codebook developed from the phase 1 analysis. The codes began with, and remained close to, the questions of the initial interview guide, with adjustments for a longitudinal perspective, that explored the Veterans’ experiences receiving information, concerns and emotional responses, desire for more information and ideas for improvement. Additional codes were added for issues and concerns that arose in reviewing these transcripts, leading to a more robust codebook—e.g., ‘more, less or the same’ under the theme of longitudinal changes in level of distress. After the codebook was adjusted, DRS and SEG independently reviewed and coded the original two transcripts and an additional two transcripts. CGS, DRS and SEG then reviewed the same four transcripts to discuss and assess discrepancies. We achieved more than our predetermined 80% level of agreement demonstrating trustworthiness of the analyses. A consensus process was used to resolve disagreements, adjudicated by the principal investigator (CGS). Saturation of most qualitative themes was achieved. The remaining interviews were independently coded by DRS and SEG using the established codebook. ATLAS.ti (Berlin, Germany) was used to organise the data.

Results

Participating veterans were mostly older, white men with smoking histories (Table 1). None of them were diagnosed with lung cancer at the time of final analysis. Primary care clinicians were responsible for the care related to the nodule for all the participants. The average time from nodule diagnosis to baseline, second and third interview was 154, 438 and 648 days, respectively, which did not seem to influence the participants’ responses. Participants’ responses were organised into five major themes: Patient Knowledge, Emotional Response/Distress, Communication with the Primary Care Provider, Suggestions for Improvement, and Impact of Research Participation.

Patient knowledge

All the participants reported receiving either a telephone call or a letter relaying the results of their follow-up CT scans from their PCPs. These letters often contained ‘cut/paste’ phrases from the radiology report notifying participants of imaging results. Sometimes this letter contained information regarding the subsequent follow-up plan at the discretion of patients’ PCPs. In most cases, participants reported that this letter was confusing, did not contain enough information and did not allow an opportunity to ask questions. Similarly, most participants who received telephone calls reported that they had inadequate information about the nodule.

Over time, the participants rarely elicited more information about the nodule from their PCP because they trusted their PCP and/or took cues from them that influenced their information-seeking behaviours. In many instances, PCPs were solely responsible for ensuring adequate monitoring of the nodule without patient involvement in decision-making regarding follow-up imaging. We found that when PCPs did not communicate the follow-up plan, participants assumed that this meant no follow-up was planned. Some participants did not seek additional information because they felt adequately informed by their PCP. Other reasons participants expressed for not seeking more information from their PCPs were fears of knowing in relation to lung cancer and the prioritisation of other medical problems. Similar to findings from baseline interviews, several participants considered the nodule a low priority compared with other active or symptomatic medical diseases.

Despite several opportunities to increase participant knowledge from the initial nodule detection to follow-up notifications from PCPs, most participants expressed a persistent lack of knowledge regarding what a nodule is and the follow-up plan for future imaging. The main themes expressed by most participants at follow-up was confusion about what a nodule is, what symptoms the nodule could cause, and what procedures might occur after being told about the existence of the nodule (e.g., biopsy). A few participants did find out more information about their nodule, primarily through contact with their PCP or through their involvement in the research study (Table 2). A small number of participants obtained additional information from the library, or family members with knowledge or past experiences with pulmonary nodules. Some participants reported that online information was unhelpful because it was difficult to understand or not relevant to their situation.

Emotional response/distress

During follow-up interviews, many participants reported mild persistent distress regarding their nodule, particularly around the time of follow-up imaging. Participants’ lung cancer concerns seemed to remain the primary contributor to this persistent distress during follow-up. When discussing distress related to the nodule, Veteran A-V3 stated that ‘I’m 84, I’m going to die of something, but I’d really not [like to] die of lung cancer.’ Even though the participants did have a lack of understanding of pulmonary nodules, most associated them with lung cancer as Veteran P-V2 stated ‘…I still don’t really understand what they [nodules] are. But I assume they’re associated with lung cancer. And that’s all I know.’ The association between the nodule and participants’ lung cancer concerns were mainly driven by current or previous smoking history as Veteran G-V2 stated, ‘I’m a good candidate for cancer, I smoked for years.’

Overall, most participants reported that their distress decreased since the initial nodule detection (Table 3). Among participants who reported moderate/severe distress during the initial interview, most of them also reported that their distress had decreased during follow-up. In those who reported persistent distress, the length of time waiting for follow-up CT scans and results was a common cause of concern. Over time, participant distress was mitigated owing to several factors, including a lack of symptoms attributed to the nodule, favourable follow-up CT results and patients’ perception that their provider was not worried about the nodule. Many participants reported taking cues, both verbal and nonverbal, from their PCPs, which decreased their distress. If the PCPs ‘didn’t sound anxious or anything’ or were perceived as ‘really reassuring’ and ‘very positive’ when delivering results, participants were reassured and reported decreased distress.

Themes regarding the impact of distress on participants’ decisions regarding smoking cessation did not reach saturation, as few participants were current smokers. Veteran C-V2 felt if the nodule was lung cancer, then there was no reason to consider quitting ‘…if I was diagnosed with lung cancer and I’ve got 6 months to live, I’d probably still smoke.’ Veteran J-V2 used the nodule detection as a teachable moment to inspire previous unsuccessful cessation attempts, ‘Sure, emphysema isn’t all that good to have, but it’s not cancer. I’m making a concerted effort right now to quit [smoking].’

Communication with the primary care provider

During follow-up, participants who had face-to-face or telephone discussions with their PCP regarding nodule changes appreciated and desired this mode of communication, as it afforded a back-and-forth exchange and opportunity to ask questions. These follow-up interactions were just as important to participants as their initial nodule notifications. Some participants also reported that the length of their relationship and previous positive experiences with their PCP helped augment effective nodule communication. Most participants found reassurance and trust were the key components of the communication they desired. Veteran P-V2 explained, ‘I trust my primary care doctor. If [my PCP] told me I had nodules and they are no big deal, then I believe [my PCP].’

There were several provider and participant-related barriers to effective communication identified during follow-up. Some participants felt their PCPs were too busy and were difficult to contact. New participant-related barriers at follow-up included the following: participants forgot to ask their PCP about the nodule during routine office appointments or reasoned the nodule was insignificant and not worth discussing because they were asymptomatic over time, ‘Well I’m curious of course, but it’s not causing me any immediate discomfort or anything like that so you don’t know it’s there,’ and ‘Oh well I don’t know. As long as it’s not interfering with my life or anything, who gives a shit?’ as Veteran N-V2 stated. During follow-up interviews, participants continued to take cues from their PCPs during nodule discussions at visits, reasoning that if PCPs did not bring it up, the nodule must not be significant.

Patients’ suggestions for improvement

Participants’ dislike of letter notification for CT scan results extended from the initial nodule detection to follow-up notifications. Most participants indicated that letters were appropriate if they were followed up by direct communication with a provider. Suggestions for letter notification improvements included providing a rating or scale regarding the amount a subject should be concerned about the nodule. During follow-up, participants wanted more information about how a nodule is managed, and asked for information on signs and symptoms of a nodule that should prompt more urgent medical care. Participants desired more information on the risk of lung cancer (Table 4).

Impact of research participation

We hypothesised that contacting potential participants via study letter might increase their distress about their nodule, and interviews might actually heighten these emotions. Some participants reported that this was the effect of the baseline study letter: ‘The worry really started coming, the actual worry started coming is when I got the letter from you guys [research]’ as Veteran Q-V2 stated. However, participation in the interviews over time seemed to decrease distress for these same patients: ‘By you [research] telling me that it’s unnecessary to do another CT scan and that basically it shouldn’t grow anymore, that’s encouraging’ as Veteran F-V3 stated, and ‘...cause you guys [research] told me that they hardly ever grow and stuff. So after meeting you that was a positive experience- you guys are alright’ as veteran D-V2 stated. Overall, study interviews seemed to decrease participants’ distress.

Discussion

Main findings

We previously reported that Veterans with incidental pulmonary nodule did not understand the term ‘nodule’ or the follow-up plan and most experienced distress, related to fears of malignancy, although they were unaware of their lung cancer risk. This study is the first to provide longitudinal qualitative information among patients with incidentally detected pulmonary nodules. Despite up to 2 years of follow-up, many patients had persistently inadequate knowledge of pulmonary nodules, the follow-up plan and their lung cancer risk. Providers’ communication strategies, mostly mail notification, may have contributed to patients’ passive role in information-seeking, which probably diminished their knowledge. Patients’ distress decreased over time from the initial detection of the nodule; however, it often increased around the time of follow-up imaging and was persistent in others. Patients overwhelmingly preferred direct, personal communication. Patients particularly valued reassurance, an accurate discussion of lung cancer risk, and the opportunity to ask questions about the nodule.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

Patients’ have been previously shown to have emotional responses to incidental nodule detection.9–11,22 In addition, providers’ initial communication regarding nodule detection does affect patients’ perceptions and distress.9 Distress of this type may lead to poor adherence with further evaluations, as has been described in the context of screening for other cancers.14–18 Our patients had a poor understanding of the follow-up plan, which may predispose them to nonadherence with medical evaluations; however, their participation in our study biased any examination of adherence. Neither longitudinal changes in patients’ distress over time nor the impact of patients’ knowledge of an incidental nodule and the follow-up plan on their distress have been previously examined. The psychosocial impact of longitudinal incidental nodule follow-up deserves greater attention considering the potential consequences on patients’ well-being, such as distress, and adherence to subsequent medical care. The abundance of incidental pulmonary nodules detected annually in the United States2,3 demonstrates the significance of our findings.

Pulmonary nodules are small (<3 cm), rounded, well-circumscribed radiographic opacities surrounded by normal aerated lung.28 Nodule follow-up is based on lung cancer risk, which is most dependent on nodule size and patients’ smoking history.6 As most small nodules are not early lung cancer and the risk of spread is low over a short time interval, most guidelines recommend active surveillance with chest imaging instead of invasive procedures.6,7 On the basis of the lung cancer mortality benefit of the National Lung Screening Trial,5 multiple organisations recommend lung cancer screening to high-risk individuals. It is estimated that 8.6–10 million Americans would meet the National Lung Screening Trial criteria for lung cancer screening annually.29,30

Implications for future research, policy and practice

Overwhelmingly, patients wanted more information about their pulmonary nodule and their risk of lung cancer. To enhance this process, it is important to ask patients what they expect at the outset of the encounter to help define roles and to prevent assumptions.31 Patients preferred direct to indirect communication in this and previous studies,9 and patients felt notification letters should serve as an adjunct and not as a replacement for direct communication. Communication about risks is difficult, as common terms such as probably, unlikely and rarely are not well defined or understood.32 Instead, portrayal of risk and satisfaction with decisions may be enhanced using decisional aids, data depicted in pictures, or summary tables.32,33 Wide variations exist in provider communication strategies for delivering bad news,34–36 but all participants made a connection between the nodule and lung cancer despite a lack of knowledge. Therefore, the inclusion of lung cancer risks should be a key component of nodule discussions. Systems-based resources should be developed to support providers to engage in PCC. These resources may include outlines for providers highlighting key strategies for enhanced communication, as well as patient educational materials. More research is needed particularly among health-care systems with large lung cancer screening programmes to help develop evidence-based resources for providers and patients. Using patients’ suggestions, preferences and addressing their concerns may serve as an organising framework for PCC strategies during the evaluation process (Table 5).

Strengths and limitations of this study

There are study limitations. This study was conducted among mostly male, elderly veterans. We enrolled patients only after permission from their PCP, perhaps creating a selection bias for patients with more knowledge and better communication. The time between the interview and imaging study was variable, and thus recall bias may influence findings. Several participants indicated that their distress decreased as a result of study interviews, likely causing us to underestimate distress in clinical settings. Patients’ perceived quality of communication may be affected by their lung cancer concerns. Patients with probable lung cancer often report lower communication scores with providers and are more likely to feel they have not had enough time or opportunity to voice distress and ask questions.37 Therefore, patients’ lung cancer concerns, which were prevalent, may have affected perceived communication. Owing to sample size constraints, themes regarding the impact of distress on participants’ decisions regarding smoking cessation did not reach saturation, which may reduce the quality of this evidence.

Conclusions

Developing systematic resources to improve patients’ knowledge, reduce their distress and refine PCPs’ communication strategies in order to enhance patients’ satisfaction, adherence and outcomes should be essential components of lung cancer screening programmes and other settings where pulmonary nodule detection is common.

References

Holden WE, Lewinsohn DM, Osborne ML, Griffin C, Spencer A, Duncan C et al. Use of a clinical pathway to manage unsuspected radiographic findings. Chest 2004; 125: 1753–1760.

Ost D, Fein AM, Feinsilver SH . Clinical practice. the solitary pulmonary nodule. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 2535–2542.

Brenner DJ, Hall EJ . Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 2277–2284.

Moyer VA, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160: 330–338.

National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 395–409.

Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, Mazzone PJ, Midthun DE, Naidich DP et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd edn: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013; 143: e93S–e120S.

MacMahon H, Austin JH, Gamsu G, Herold CJ, Jett JR, Naidich DP et al. Guidelines for management of small pulmonary nodules detected on CT scans: a statement from the fleischner society. Radiology 2005; 237: 395–400.

Slatore CG, Sullivan DR, Pappas M, Humphrey LL . Patient-centered outcomes among lung cancer screening recipients with computed tomography: a systematic review. J Thorac Oncol 2014; 9: 927–934.

Wiener RS, Gould MK, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Clark JA . What do you mean, a spot?: a qualitative analysis of patients' reactions to discussions with their physicians about pulmonary nodules. Chest 2013; 143: 672–677.

Paris C, Maurel M, Luc A, Stoufflet A, Pairon JC, Letourneux M . CT scan screening is associated with increased distress among subjects of the APExS. BMC Public Health 2010; 10: 647–2458-10-647.

Wiener RS, Gould MK, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Clark JA . 'The thing is not knowing': patients' perspectives on surveillance of an indeterminate pulmonary nodule. Health Expect (e-pub ahead of print 16 December 2012; doi:10.1111/hex.12036).

Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Zvolensky MJ . Distress tolerance and early smoking lapse. Clin Psychol Rev 2005; 25: 713–733.

Cohen S, Lichtenstein E . Perceived stress, quitting smoking, and smoking relapse. Health Psychol 1990; 9: 466–478.

Lerman C, Daly M, Sands C, Balshem A, Lustbader E, Heggan T et al. Mammography adherence and psychological distress among women at risk for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993; 85: 1074–1080.

O'Donnell S, Goldstein B, Dimatteo MR, Fox SA, John CR, Obrzut JE . Adherence to mammography and colorectal cancer screening in women 50-80 years of age the role of psychological distress. Womens Health Issues 2010; 20: 343–349.

Brewer NT, Salz T, Lillie SE . Systematic review: the long-term effects of false-positive mammograms. Ann Intern Med. 2007; 146: 502–510.

Donato F, Bollani A, Spiazzi R, Soldo M, Pasquale L, Monarca S et al. Factors associated with non-participation of women in a breast cancer screening programme in a town in northern italy. J Epidemiol Community Health 1991; 45: 59–64.

Lerman C, Rimer B, Trock B, Balshem A, Engstrom PF . Factors associated with repeat adherence to breast cancer screening. Prev Med 1990; 19: 279–290.

Presidental Commision for the Study of Bioethical Issues. Anticipate and communicate: Ethical managament of incidental and secondary findings in the clinical, research, and direct-to-consumer contexts. December 2013.

Wensing M, Jung HP, Mainz J, Olesen F, Grol R . A systematic review of the literature on patient priorities for general practice care. part 1: description of the research domain. Soc Sci Med 1998; 47: 1573–1588.

Deledda G, Moretti F, Rimondini M, Zimmermann C . How patients want their doctor to communicate. A literature review on primary care patients' perspective. Patient Educ Couns 2013; 90: 297–306.

Slatore CG, Press N, Au DH, Curtis JR, Wiener RS, Ganzini L . What the heck is a "nodule"? A qualitative study of veterans with pulmonary nodules. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2013; 10: 330–335.

Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry MH 3rd, Morley JE . Comparison of the saint louis university mental status examination and the mini-mental state examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder--a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006; 14: 900–910.

Street RL Jr, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM . How does communication heal? pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns 2009; 74: 295–301.

Sandelowski M, Barroso J . Classifying the findings in qualitative studies. Qual Health Res 2003; 13: 905–923.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE . Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005; 15: 1277–1288.

Miles M, Huberman A . Qualitative data analysis: a sourcebook of new methods. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods, 2nd edn. SAGE Publications, Inc: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1994.

Tuddenham WJ . Glossary of terms for thoracic radiology: recommendations of the nomenclature committee of the fleischner society. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1984; 143: 509–517.

Doria-Rose VP, White MC, Klabunde CN, Nadel MR, Richards TB, McNeel TS et al. Use of lung cancer screening tests in the United States: results from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2012; 21: 1049–1059.

Ma J, Ward EM, Smith R, Jemal A . Annual number of lung cancer deaths potentially avertable by screening in the united states. Cancer 2013; 119: 1381–1385.

McCormack LA, Treiman K, Rupert D, Williams-Piehota P, Nadler E, Arora NK et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in cancer care: a literature review and the development of a systematic approach. Soc Sci Med 2011; 72: 1085–1095.

Edwards A, Elwyn G, Mulley A . Explaining risks: turning numerical data into meaningful pictures. BMJ 2002; 324: 827–830.

Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA . Helping patients decide: ten steps to better risk communication. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011; 103: 1436–1443.

Ptacek JT, Eberhardt TL . Breaking bad news. A review of the literature. JAMA 1996; 276: 496–502.

Ptacek JT, Ptacek JJ, Ellison NM . "I'm sorry to tell you..." physicians' reports of breaking bad news. J Behav Med 2001; 24: 205–217.

Girgis A, Sanson-Fisher RW . Breaking bad news: consensus guidelines for medical practitioners. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13: 2449–2456.

Dalton AF, Bunton AJ, Cykert S, Corbie-Smith G, Dilworth-Anderson P, McGuire FR et al. Patient characteristics associated with favorable perceptions of patient-provider communication in early-stage lung cancer treatment. J Health Commun 2014; 19: 532–544.

Acknowledgements

CGS is supported by VA HSR&D Career Development Award (CDP 11–227). DRS is supported by 5KL2TR000152-08 funded through the National Institutes of Health and National Center for Research Resources through the OHSU Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (OCTRI). DRS, LG, CGS and SEG are supported by resources from the VA Portland Health Care System, Portland, OR, USA. The Department of Veterans Affairs did not have a role in the conduct of the study, in the collection, management, analysis, interpretation of data or in the preparation of the manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government.

Funding

The authors declare that no funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DRS, SEG, LG, LH and CGS were involved in the conception and design, the analysis and interpretation of the data, critical revision of the article for important intellectual content and final approval of the article; drafting of the article was done by DRS and CGS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Sullivan, D., Golden, S., Ganzini, L. et al. ‘I still don’t know diddly’: a longitudinal qualitative study of patients’ knowledge and distress while undergoing evaluation of incidental pulmonary nodules. npj Prim Care Resp Med 25, 15028 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/npjpcrm.2015.28

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npjpcrm.2015.28