Abstract

Advances in the spatial resolution of modern analytical techniques have tremendously augmented the scientific insight gained from the analysis of natural samples. Yet, while techniques for the elemental and structural characterization of samples have achieved sub-nanometre spatial resolution, infrared spectral mapping of geochemical samples at vibrational ‘fingerprint’ wavelengths has remained restricted to spatial scales >10 μm. Nevertheless, infrared spectroscopy remains an invaluable contactless probe of chemical structure, details of which offer clues to the formation history of minerals. Here we report on the successful implementation of infrared near-field imaging, spectroscopy and analysis techniques capable of sub-micron scale mineral identification within natural samples, including a chondrule from the Murchison meteorite and a cometary dust grain (Iris) from NASA's Stardust mission. Complementary to scanning electron microscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and transmission electron microscopy probes, this work evidences a similarity between chondritic and cometary materials, and inaugurates a new era of infrared nano-spectroscopy applied to small and invaluable extraterrestrial samples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infrared (IR) spectroscopy in the frequency range of 400–4,000 cm−1 (λ=25–2.5 μm) is widely used for the identification of chemical compositions both in the laboratory and in remote observations. However, use of this technique for studying sub-micron scale heterogeneity characteristic of natural samples or individual micron-sized samples such as the cometary dust grains retrieved by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)’s Stardust mission1,2,3,4,5,6 is severely hampered by the spatial resolution afforded by the diffraction limit and the wavelength of IR light7,8. This limitation rules out direct investigations of both sub-micron samples and sub-micron inclusions in larger heterogeneous samples by conventional Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Yet, as acknowledged among the first-reported findings from the Stardust mission, advances in analytic techniques promise to expose new secrets about the origin and evolution of the solar system contained in the recovered microscopic cometary grains1. With regard to IR spectroscopy, this claim cannot be overstated given its reputation as the chemical ‘fingerprinting’ technique of choice. Moreover, the return of invaluable micron-scale samples from spacecraft missions such as Stardust poses an urgent need for new non-destructive, even non-perturbative, nanoscale probes of chemical structure.

In recent years, developments in scattering-type near-field scanning optical microscopy (s-SNOM) have enabled acquisition of IR spectral information at sub-micron length scales17,18. Conceptually, this imaging technique relies on an atomic force microscope (AFM) tip acting as an optical antenna (or ‘near-field probe’) to focus incident electromagnetic radiation to areas smaller than the wavelength of incident light. Recent applications of the technique include studies of plasmons in graphene and spatial mapping of electronic transitions in correlated oxides19,20,21,22,23,24,25. By incorporating a broadband mid-IR (MIR) laser and spectroscopic interferometer into an s-SNOM system, investigators have now demonstrated 20 -nm-resolved IR nano-spectroscopy (nanoFTIR)26,27,28,29,30,31. Yet, to the best of our knowledge, heretofore the only attempt at near-field imaging and spectroscopy of natural geochemical samples has utilized a conventional (thermal) IR source to produce maps of spectral features limited to ~1 μm resolution in a primitive meteorite32. However, the absence of background suppression schemes requisite for near-field microscopy places much doubt on their study’s efficacy as a bona fide sub-diffraction optical probe.

Complemented by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) probes, here we report on the application of IR s-SNOM and nanoFTIR with a metallic near-field probe to identify and distinguish silicate minerals in a sample of Comet 81P/Wild 2 and a portion of the Murchison meteorite, a CM2 chondrite comprised of organics and stony grains (chondrules), with sub-micron (~20 nm) lateral resolution. We also demonstrate that nanoscale IR spectroscopy can sense elemental concentration gradients at the level of a few percent caused by rapid cooling, identify sub-micron intergrowths at the confluence of distinct lattice structures, providing evidence for shock within a chondrule, and directly reveal juxtaposed crystalline and amorphous silicates in the Iris cometary grain. NanoFTIR measurements of Iris are consistent with mounting evidence3,33,34 (Z. Gainsforth et al., manuscript in preparation) that igneous materials formed at high temperatures deep in the solar nebula were incorporated into cometary bodies, advancing a surprising scenario whereby planetary materials must have been mixed over the grandest scales into the outer solar system1.

Results

Material identification with nanoFTIR

Material identification in spatial volumes smaller than the wavelength of light through s-SNOM requires establishing a physical relationship between an incident electromagnetic field, the dielectric properties of the material directly underneath the probe tip, and the consequently scattered electromagnetic field recorded by the microscope (for our experimental set-up see Methods). In the simplest model of s-SNOM, based on the combination of an AFM with IR optics, the incident electromagnetic field irradiates the AFM probe, inducing a dipole of electric charge in its tip, as shown schematically in Fig. 1. In accordance with the boundary conditions of Maxwell’s equations at the surface of the dielectric material directly underneath, an interacting mirror dipole is induced within the sample. An electric near-field interaction between the tip and charges from its mirror image modifies the amplitude and phase of backscattered radiation from the probe, which functions therefore as an optical antenna highly sensitive to the dielectric environment near its tip. Using suitable background suppression and techniques, interferometric detection of this backscattered radiation while scanning the sample beneath the tip provides sensitivity to the sample’s local permittivity at a resolution comparable to the radius of curvature at the tip apex (≈20 nm).

(a) The probe tip interacts with at a sample region characterized locally by permittivity ε, a function of wavelength. Scale bar: 10 μm. (b) The incident electromagnetic field Einc induces a strong dipole moment in the tip, which interacts with a mirror dipole in the sample whose strength is determined by the local permittivity. This interaction sensitively affects the tip's vertical polarization pz, therefore locally modulating the amplitude and phase of the tip-scattered field Escat. Scale bar: 100 nm.

A rudimentary connection between the amplitude and phase of this detected radiation (‘near-field signal’) and the optical properties of the sample can be achieved through a simple or extended dipole approximation35,36. Recently, we have developed more sophisticated models of the optical near-field interaction between the probe and the sample and have applied them with excellent results to the study of graphene–substrate optical coupling20 and oxide thin films25. Our latest and most accurate model37 interrelates the scattered signal with the dielectric function and optical reflection coefficient of the sample (Supplementary Fig. 1), the same reflectivity accessed by conventional far-field FTIR spectroscopy. Likewise, the imaginary component of the sample’s refractive index, often called the IR extinction or absorption coefficient, describes its IR absorption efficiency. Maxima in the frequency-dependent IR absorption coefficient correspond directly to the absorption peaks of ‘fingerprint’ molecular vibrations measured by conventional transmission-mode FTIR or total internal reflectance spectroscopies.

However, although related, the frequency-dependent scattered field measured by nanoFTIR is not equivalent to a conventional FTIR absorption spectrum. Surface phonons couple particularly strongly to a near-field probe as their electric dipole vibrates resonantly with the incident probe field, shifting peaks in the scattering spectrum to lower energy by an amount commensurate with their strength38. Quantitative comparisons between a sample’s near-field spectrum (for example, Fig. 2) and its associated conventional FTIR absorption spectrum require that the geometry of the near-field interaction be explicitly taken into account by a realistic model of the tip, such as the one used in this work to ‘invert’ the scattering amplitude and phase spectra to extract nano-resolved dielectric properties of the material underneath the tip apex28,37. Elementary relations connecting the reflection coefficient to the IR absorption coefficient have been presented elsewhere29 and, for characterization of the cometary particle Iris, we apply these here for the first time to the direct identification of silicate minerals using nanoFTIR (see Methods).

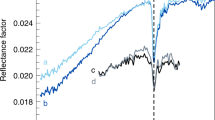

A nonlinear optical crystal (GaSe) is used to combine two near-infrared sources in a difference frequency generation scheme, producing coherent MIR radiation that is frequency tunable with a 300-cm−1 bandwidth. This beam is focused onto the AFM tip, resulting in strong near-field interactions with the sample and a backscattered field (characterized by amplitude and phase) modulated at the probe-tapping frequency and detected by the HgCdTe (MCT) detector. Interfering this light with a continuously delayed reference beam (scanning mirror) and demodulating at harmonics of the tapping frequency produces an interferogram whose Fourier transform constitutes the desired near-field scattering spectrum. The displayed scattering amplitude and phase spectra are obtained for a forsterite crystal standard (San Carlos olivine).

NanoFTIR characterization of a chondrule

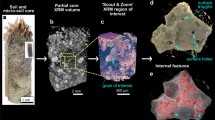

Figure 2 schematically depicts our s-SNOM and nanoFTIR system (see Methods) and presents characteristic scattering spectra for a standard crystal of forsterite, one of the most abundant minerals in the solar system and common chondrule constituent. We applied this system first to characterize a sub-millimetre chondrule within the Murchison meteorite, a CM2 chondrite notable for its abundant organics and aqueously altered minerals (preparation in Methods). The chondrule was first coated with ≈15 nm of conductive carbon and imaged by SEM; Fig. 3a,b displays backscattered electron images. Elemental compositions (displayed in Fig. 3d) were measured at <500 nm resolution using EDS. The chondrule was then sputtered with argon to ablate the carbon coat and subsequently imaged with s-SNOM in monochromatic mode (pseudo-heterodyne detection technique39) taking illumination from a CO2 laser at 890 cm−1 to quickly reveal an IR contrast map of the region (Fig. 3c). Optically reflective or vibrationally resonant materials at this frequency display positive imaging contrast. IR scattering contrast is evident among microscopic crystallites, a bright metallic inclusion (iron), and a dark non-resonant background of carbonaceous material (including preparation epoxy).

(a) Backscattered secondary electron (BSE) image of the polished Murchison sample region, with red indicating the field of view for the nanoFTIR images. Scale bar: 100 μm. (b) BSE image of this boxed region in a where an iron metal grain can be clearly seen. Scale bar: 5 μm. (c) Infrared near-field amplitude image acquired at w=890 cm−1 superimposed on simultaneously acquired AFM topography (range: 500 nm). Positions of the three (1–3) nanoFTIR line scans presented in Fig. 4 are shown by dashed lines. Scale bar: 5 μm. (d) Composite EDS map of the same region again showing the positions of the three (1–3) nanoFTIR line scans presented in Fig. 4. (Green=forsterite, purple=augite, orange=aluminous orthopyroxene.)

The chondrule contains Al-, Mg- and Ca-rich silicate phases, and EDS identifies Mg-rich regions (green in Fig. 3d) as forsterite (Mg2SiO4). To distinguish extant mineral phases through their vibrational signatures, we collected spectroscopic nanoFTIR line scans 8–10 μm in length across three distinct microcrystalline subregions, acquiring scattered amplitude and phase spectra every 50 nm over the frequency range relevant to the strongly identifying vibrational modes of the silicate minerals (800–1150, cm−1). Scattering amplitude spectra from these line scans are displayed in Fig. 4, exhibiting several spectroscopically distinct subregions. These line scans verify the ubiquitous presence of forsterite (green in Fig. 4) by comparing with the reference spectra (Fig. 2). Compositional boundaries sharper than 100 nm and distinct silicates as small as 200 nm are resolved spectroscopically. Metallic composition of the large iron inclusion (red spectrum in Fig. 4, line scan 2) was confirmed by its exceptionally strong and spectrally uniform induced scattering amplitude, although several superimposed ‘void bands’ provide evidence for a surface oxide layer of probable terrestrial origin, as from ‘gamma’-FeOOH (lepidocrocite) that exhibits identifying MIR vibrational modes40. These resonances are optically ‘sensed’ through near-field coupling with their metallic host, as leveraged previously for the detection of weak molecular vibrations using metal nanoantennas41.

(Line scans) Three nanoFTIR line scans (scattering amplitude versus position) through a chondrule of the Murchison meteorite identify distinct crystalline phases according to their unique near-field spectra; positions of line scan acquisitions are shown in Fig. 3c,d. Line scan 1: a sequence of forsterite (green arrow), Al-poor (blue) and Al-rich (purple) augite. Line scan 2: an iron inclusion with suspected phonon-resonant oxide layer (red, amplitude reduced by 2 × ), followed by forsterite (green), aluminous orthopyroxene (orange), Al-rich and Al-poor augites. Comparatively broad phonon peaks in the final three regions suggest structural disorder. Line scan 3: A progression of aluminous orthopyroxene, augite and forsterite. (Averaged spectra) Position-averaged spectra of these distinct regions are similarly colour coded (offset and re-scaled for clarity, dashes indicate zero lines).

Stoichiometries for Al- and Ca-rich regions measured by EDS are consistent with several minerals formed from linear chains of silicate tetrahedra (inosilicates) but were insufficient to unambiguously identify the associated mineral species since EDS is insensitive to the presence of –OH. In such cases, concrete identification of mineral phases has conventionally relied on complementary analytic techniques including X-ray diffraction (XRD), TEM and various transmission-mode X-ray spectroscopies, which although powerful, demand either sample volumes of many cubic microns or thin slices excised from the bulk sample at the cost of man-hours and destroying the nearby sample. Even the electron backscatter diffraction technique, a powerful high-resolution probe of crystal structure (insensitive to glassy structure), requires careful deposition of a conductor over insulating minerals42. In stark contrast, nanoFTIR measurements are fundamentally non-destructive, requiring no special sample preparation beyond a surface polish with micron-scale smoothness, which even then might be omitted for smooth or terraced sample regions. Furthermore, since mid-IR energies are insufficient to break chemical bonds or cause ionization, risk to the sample from beam damage during the nanoFTIR measurement is completely implausible when using illuminating radiation intensities <5 mW (0.5 mW were used in this work)43. Nevertheless, a lamella along line scan 3 (indicated in Fig. 3c,d) was extracted from our Murchison meteorite sample by focused ion beam and examined by TEM (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Fig. 4). In this case, we undertook this measure to unambiguously establish a correlative TEM and nanoFTIR spectroscopy study of the same region44. Whereas the complete focused ion milling and TEM study required three days of instrument time, nanoFTIR measurements were completed within 3 h.

Analysis of nanoFTIR data inherits from the rich existing literature of vibrational spectroscopy obtained from bulk terrestrial minerals by conventional FTIR. Pyroxenes constitute a solid solution series of single-chain silicates with chemical formula M1M2T2O6 (M1, M2 denoting cation sites and T the tetrahedral site, typically Si or Al) including Mg-rich (enstatite) and Ca-rich (augite) members common among chondritic meteorites. Established IR absorption spectra for enstatite45,46 match vibrational bands of the first several nanoFTIR spectra (Supplementary Fig. 3) of line scan 3 (Fig. 4 in orange), consistent with Mg-dominated occupancy in M1 and M2 sites as confirmed by TEM and EDS (Fig. 5b). However, EDS also indicates the Murchison Mg-rich pyroxene contains 5.3 wt% aluminium, making this phase aluminous orthopyroxene (OPX). A discrete change in vibrational character is observed by nanoFTIR upon entry to the Ca-rich phase, which compares favourably to attenuated total internal reflectance spectra of augite47,48. Comparatively, such a concrete identification for this compound was otherwise impossible via EDS, since the measured elemental stoichiometry admitted other mineral assignments (Supplementary Fig. 3). The abrupt disappearance and replacement of several vibrational modes displayed in Fig. 5a (orange to purple) matches an abrupt compositional change observed by EDS with a reduction in Mg by 10 wt% and an increase in Ca by 14 wt%. Accordingly, a phase transition from OPX to CPX (clinopyroxene) was measured by selected area diffraction in TEM (Supplementary Methods). While existing IR studies fail to observe marked differences in vibrational character between ortho- and clinoenstatites46,49, the monoclinic structure of augite presents yet a distinct space group, C2/c versus the P21/c of clinoenstatite. We therefore attribute the resolved boundary in nanoFTIR to differential cation occupations in M1 and M2 (ref. 50), establishing nanoFTIR as a sensitive indicator of subtle shifts in elemental chemistry at the nanoscale. We infer these cation concentrations resulted from strong temperature gradients as the host pyroxene rapidly crystallized.

(a) Modal frequencies versus position resolved by nanoFTIR through line scan 3 of the Murchison meteorite. Forsterite (green) gives way to pyroxene phases: calcium-rich clinopyroxene (CPX, purple) and an aluminous orthopyroxene (OPX, orange). Modulations in modal frequencies correlate with increases in cation concentrations at the few percent level as determined by transmission electron EDS (b). The spectroscopically distinct 300-nm wide transition band between CPX and OPX observed by nanoFTIR is attributed to an OPX/CPX superlattice (OCPX, dashed region). (c) Transmission electron diffraction collected from the respective pyroxene phases confirms the aperiodic lattice superstructure of this band, indicative of crystal shock, as resolved also by (d) TEM imaging. Scale bar: 200 nm. (e) High-resolution TEM zoom in view onto the boxed region of (d) resolves the OPX/OCPX interface. Scale bar: 25 nm.

Our correlative TEM subsequently resolved the transition zone between OPX and CPX phases (Fig. 5d) and electron diffraction verified our identification of phases (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 4). Moreover, a 300-nm-wide superlattice of CPX and OPX lamella (marked OCPX) is revealed through electron diffraction as a continuum of reflections along the a* axis and shows contrast in high-resolution and darkfield TEM imaging. Although only a few hundred unit cells across, this intergrowth region was first resolved by nanoFTIR, manifesting an anomalous IR vibrational signature at several spectroscopy positions across the OPX/CPX interface in Fig. 5a, particularly through the sharp ‘kink’ in several vibrational modes suspiciously characteristic of interlayer-coupled mode repulsion. The lack of such effect for the 1,050-cm−1 mode likely associates with its short-range vibrational nature—a ‘breathing’ mode among isolated silicate tetrahedra (Supplementary Methods)—unaffected by broken long-range crystal symmetry. Such interphase ortho/clinopyroxene regions are a common indicator of crystal shock and rapid cooling51. Here we interpret the structure as a consequence of collisional events in the history of Murchison’s parent body, in particular the event that may have caused the host chondrule to shatter (Fig. 3a and Supplementary methods). Sensitivity to these shock phenomena establishes nanoFTIR as a promising non-destructive probe of collisional histories among invaluable extraterrestrial samples.

Figure 5a highlights a notable shift in modal frequencies (especially near 950 cm−1 and 1,050 cm−1) resolved by nanoFTIR at sub-micron scales in line scan 3, coincident with further lattice displacement of Mg by heavier Ca and Al in CPX at the few-percent level on approach to the adjacent forsterite (Fig. 5b). These vibrational shifts associate with perturbations in the crystal’s silicate tetrahedral bond lengths, mediated by commensurate changes in local cation concentration (Supplementary Methods). Vibrational spectroscopy via nanoFTIR can evidently provide a sensitive sub-micron indicator of cation lattice coordination and concentration variations at the few-percent level. We propose that nanoFTIR might be deployed on extraterrestrial pyroxenes to detect T-site occupation by Al and Fe3+ that, when compared with other petrographic characteristics, can provide evidence for aqueous alteration or for high fugacity during formation in the solar nebula.

NanoFTIR characterization of a cometary grain

We next applied nanoFTIR to a cometary particle returned from Comet 81P/Wild 2 by the NASA’s Stardust recovery mission, a sample for which the non-destructive nature of our probe is of paramount importance. The cometary grain C2052,12,74 (‘Iris’) was first characterized by synchrotron X-ray, electron, and ion microscopies, as well as secondary ion mass spectroscopy33. On a surface of Iris exposed by ultramicrotomy, we first utilized our nanoFTIR system to acquire a broadband integrated image of the particle (Fig. 6a,b). This mode of imaging permits rapid acquisition of relatively large IR maps of the sample in which local contrast indicates the optical response amplitude integrated over the bandwidth of illumination (800–1,150 cm−1). For example, chunks of Pb–In alloy introduced during sample preparation for secondary ion mass spectroscopy are brightly resolved at the particle periphery. This same region of Iris was also imaged with EDS as shown in Fig. 6c, indicating clear correspondence between the mesostasis region identified previously33 (Z. Gainsforth et al., manuscript in preparation) and the elemental EDS map. We acquired a nanoFTIR line scan 7 μm in length along the dotted line indicated in Fig. 6b, measuring local scattering amplitude and phase spectra every 100 nm across the mesostasis between two forsterite crystals, and utilized the aforementioned inversion procedure (detailed in Methods and Supplementary Figs 1 and 2) to convert our scattering spectra to a more appropriate series of IR absorption spectra (Fig. 6d) suitable for comparison against conventional IR absorption spectra for candidate silicate minerals52,53,54.

(a) Broadband spectrally integrated (800–1,150 cm−1) IR s-SNOM image of Iris. Scale bar: 5 microns. (b) Zoom onto the central region; colour-scale for spectrally integrated scattering amplitude at right, with nanoFTIR line scan position indicated by the arrow. (c) Composite EDS map displaying relative atomic concentrations of aluminium (red), sodium (green), and silicon (blue). Silicon-rich forsterite crystals as well as the surrounding SiO2 aerogel appear blue, whereas the groundmass reveals feldspar (white) and glass (red and pink). Scale bar: 5 microns. (d) Using a realistic model of the near-field probe-sample interaction, position-resolved IR absorption spectra were extracted from the nanoFTIR line scan across two forsterite crystals (regions labelled A, E) and three distinct glassy phases of plagioclase and mesostasis (B, C, D). (e) Literature IR absorption spectra from forsterite, various plagioclase feldspars and amorphous silica. Oligoclase and anorthite spectra are from powdered samples51, silica from a thin film53 and all others from bulk (crystalline) samples52. (f) Region-averaged IR absorption spectra extracted from nanoFTIR line scan positions indicated in a (labelled by region). Extracted forsterite spectra agree well with reported absorption spectra52, whereas plagioclase regions exhibit albite (Ab)-rich, anorthite (An)-rich and glassy signatures according to their phonon absorption frequencies. Sharp anorthite and oligoclase nanoFTIR peaks imply crystalline material, whereas reported spectra for powders (e) display added broadening57,59. The surprisingly broad albite peak resolved by nanoFTIR is consistent with strong Al–Si disorder54.

Iris is known to consist of olivines set in a groundmass of plagioclase (a solid-solution series of feldspar minerals) with composition 6–26 mol% in Ca-rich anorthite (An) and Na-rich albitic (Ab) glass that formed from quenched igneous cooling. Since the groundmass grew under non-equilibrium conditions, the crystalline plagioclase presents a continuum of chemical compositions including albite and Ca-rich oligoclase (compositionally intermediate between Ab and An). The remaining liquid was unable to crystallize at all because of rapid cooling. The transition from crystalline to amorphous material is observable in our line scan (Fig. 6d), wherein three distinct spectral signatures are resolved. Representative spatially averaged nanoFTIR absorption spectra derived from regions bounded by dashed lines in Fig. 6d are shown in Fig. 6f for clarity. Figure 6e displays literature-derived IR absorption spectra for mineral standards that present good matches to these regions based on a comparison of prominent IR absorption band frequencies. Spectra for the purple and red phases (Fig. 6f) exhibit vibrational bands at nearly identical frequencies but at varying intensity, consistent with An-rich and Ab-rich regions, respectively. Accordingly, EDS mapping ascribes elemental abundances from these two regions to oligoclase with a slowly varying composition of 20–26 An mol%.

Whereas the anorthite and oligoclase phonon bands resolved by nanoFTIR at 910 and 970 cm−1 appear expectedly sharper than those observed in far-field absorption spectra for powders55,56,57 at ~915 and ~990 cm−1 (Fig. 6e), the measured albite peak is notably broad (70 cm−1 full-width at half-maximum; see Supplementary Fig. 2), comparing most favourably to spectra for crystals with reduced Al–Si order in the tetrahedral site such as effected by high-temperature exposure (>1,000 K) (ref. 54). On the basis of its coincident presence among far-field IR spectra of Iris (Supplementary Fig. 5), the dip-like feature observed throughout our line scan near 950 cm−1 appears to be intrinsic in nature, whether associated with a gap in phonon modes of forsterite or with the absence of absorption between sharp peaks associated with An or oligoclase. Whereas EDS resolution was limited to about 750 nm, nanoFTIR resolves variations in spectral absorption at the scale of 100 nm. Lacking gradual shifts in absorption frequencies, the most likely explanation for such sharp well-defined variations in nanoFTIR is the detection of two centrally embedded crystallites of anorthite and oligoclase resolved at the sub-micron scale. Comparatively, TEM was also able to detect one such crystallite (Z. Gainsforth et al., manuscript in preparation) although its spatial relations were unfortunately scrambled (not atypically) from the requisite extraction of a thin microtomed slice of sample.

Moreover, Fig. 6d reveals a third phase (blue in Fig. 6f) where peak positions and amplitudes vary gradually as a function of position. EDS excludes the possibility that this region is plagioclase on the basis of stoichiometry, suggesting rather an albitic glass, and TEM diffraction and brightfield measurements verify the presence of glass in contact with oligoclase elsewhere within this particle (Z. Gainsforth et al., manuscript in preparation). NanoFTIR spectra in this region (Fig. 6d, f—blue) show the growth of a peak near 1,100 cm−1 similar to that seen in amorphous SiO2 standards53, while retaining some but not all of the peaks expected from plagioclase. This suggests an albitic glass populated by under-resolved nanocrystals of oligoclase, again indicative of rapid cooling from a melt. Demonstrably, nanoFTIR presents a novel means of optical identification and potential compositional characterization58,59 for bona fide amorphous silicate materials in returned microscale cometary dust grains, as well as in similarly sized interplanetary dust particles or aerosols. The composition of Iris shown here is decidedly inconsistent with the long-held view that comets formed in the outer solar system from agglomerated circum- or interstellar grains60, comprising—for example, dust, ice and silicates amorphized by radiation exposure. Instead, the direct IR spectroscopic evidence presented here for igneous crystalline and amorphous materials coexisting at the micron-scale within a cometary dust grain adds to mounting evidence for a common history of high-temperature formation shared by cometary and chondritic materials deep within the solar nebula33,34 (Z. Gainsforth et al., manuscript in preparation). This scenario awaits a suitable explanation for the requisite mixing of planetary materials into the outer solar system that must have enabled their incorporation among remote cometary bodies such as 81P/Wild 2 (ref. 1).

Discussion

We have shown that IR s-SNOM is capable of providing IR spectral identification of natural samples at deeply sub-micron spatial resolutions, probing details of material composition not easily accessed by conventional means. Here we demonstrate this capability within a macroscopic meteorite sample (Murchison) as well as a cometary dust grain (Iris) from NASA’s sample return mission, Stardust. Through application of a sophisticated model of the probe–sample near-field interaction, we have shown for the first time that nanoFTIR-extracted IR absorption spectra can be used to quantitatively probe and identify the underlying geochemistry of natural samples at sub-micron resolutions, enabling identification of resonance frequencies and relative levels of structural disorder in a fashion that removes the influence of complex probe–sample interactions. These samples span the size range encountered in the analysis of natural samples.

Together with corresponding elemental maps from EDS, our nanoFTIR line scans through a chondrule in Murchison clearly capture variations in minerology at sub-micron resolutions and are verified by TEM. Furthermore, our nanoFTIR line scans are capable of resolving subtle shifts in vibrational frequencies associated with small variations in silicate cation concentrations at the sub-micron scale. Future work may explore these shifts in a quantitative manner via first-principles calculations. Our nanoFTIR survey of Iris demonstrates that s-SNOM is also sensitive to contrasts in crystallinity, as indicated by the prominence and width of phonon absorption bands within the plagioclase, and future work may establish quantitative measures of disorder. Whereas the physical mechanism of nanoFTIR spectroscopy is relatively settled, and practical quantitative ‘inversion’ for the interpretation of mineral spectra is now well demonstrated here and elsewhere37, fully leveraging its sensitivity will call for a detailed empirical or ab anitio approach connecting nanoscale geochemistry to the local phonon response and associated IR permittivity.

These results highlight the high potential of nanoFTIR for geochemical studies of crystallization dynamics or other processes producing variations in the chemical environment over sub-micron length scales, inaccessible to conventional diffraction-limited FTIR. Having demonstrated the application of SNOM-based nanoFTIR for characterizing and imaging silicate minerals, it is hoped that this technique can be applied for studying the distribution of more volatile chemical components found within extraterrestrial samples. This sub-micron mapping could in turn, through strong correlations between minerals such as SiC (well-known presolar astromaterial) and organics, for example, provide new insights into the catalytic role that mineral surfaces may play in the production of prebiotic molecules in the early solar system and planetary systems at large. Finally, the ability to non-destructively characterize volatile species before more destructive/altering techniques are applied to precious and unique returned samples is a significant advance. Future applications of IR s-SNOM and nanoFTIR may also include distribution studies of individual terrestrial aerosol mixing states, examination of synthetic and natural non-equilibrium solids, and sub-micron identification of hydrated and organic chondrite phases. Furthermore, this technique should be suitable for the analysis of additional returned samples from missions including NASA’s Stardust spacecraft1,2,6 and Hayabusa61, as well as interplanetary dust particles and other primitive solar system materials possessing sub-micron heterogeneity62.

Methods

Broadband IR source and nanoFTIR implementation

NanoFTIR measurements were performed using instrumentation at the Department of Physics at the University of California, San Diego. We achieved broadband illumination of our samples using a broadband MIR-coherent source (mod. BB from www.lasnix.com), combining two near-infrared laser beams in a GaSe crystal for difference frequency generation of coherent MIR radiation (100 fs pulses, 300 cm−1 bandwidth, tunable across 600–2,500 cm−1, ~3 μW per cm−1). This beam is coupled to an asymmetric Michelson interferometer, allowing measurement of the amplitude and phase of the backscattered radiation with 3 cm−1 spectral resolution28,63. Our nanoFTIR implementation is depicted schematically in Fig. 2.

Because the scattered signal is a strong function of the distance between the near-field probe and the sample surface, we make use of the AFM probe’s tapping capability (tapping mode at a frequency Ω≈250 kHz) to modulate the scattered signal and enable distinction from background scattering. The near-exponential dependence of the near-field interaction on the tip–sample distance d implies that scattered field components modulated at harmonics nΩ with n≥2, are directly attributable to the near-field polarization of the tip. Sub-diffractional contrasts in the scattered field at these harmonics therefore correspond with variations in the local chemical composition of the sample38. NanoFTIR data presented in this work were acquired by lock-in detection of the scattered signal at the second harmonic (2Ω) of the probe’s tapping frequency, resulting in second harmonic amplitude S2 and phase ϕ2 signals, whereas imaging data utilize the third harmonic. Finally, quantitative spectral information was obtained by normalizing the frequency-dependent second harmonic signals acquired from sample regions to those spectra acquired from a reference material using the same near-field probe. A silicon wafer with a 100-nm surface layer of evaporated gold (Au) was used for normalization.

Extraction of dielectric properties from nanoFTIR spectra

The lightning rod model of probe–sample near-field interaction realistically relates the experimental measurables of s-SNOM to the sample’s dielectric properties near the probe apex. While this sophisticated model does not yield a closed-form relation, it can still be applied in the inverse sense to extract the self-consistent surface reflection coefficients  from sub-50-nm-resolved nanoFTIR spectra37, provided that sample material is bulk-like (>100 nm in thickness), the spectra are referenced to a known sample material such as gold, and that the probe geometry approximates a metal cone with rounded tip apex. The inversions performed in this work assume a tip radius of 40 nm (the sharpest feature size resolvable by concurrent AFM), a cone half-angle of 20° and probe-tapping amplitude of 60 nm, consistent with probe specifications (Arrow NCPt from NanoWorld) and measurement parameters. The ‘effective’ (indicated by brackets) dielectric constant ε(ω) and absorption coefficient κ(ω) of the material are then given by29

from sub-50-nm-resolved nanoFTIR spectra37, provided that sample material is bulk-like (>100 nm in thickness), the spectra are referenced to a known sample material such as gold, and that the probe geometry approximates a metal cone with rounded tip apex. The inversions performed in this work assume a tip radius of 40 nm (the sharpest feature size resolvable by concurrent AFM), a cone half-angle of 20° and probe-tapping amplitude of 60 nm, consistent with probe specifications (Arrow NCPt from NanoWorld) and measurement parameters. The ‘effective’ (indicated by brackets) dielectric constant ε(ω) and absorption coefficient κ(ω) of the material are then given by29

In the case of optically uni- or biaxial crystals, the dielectric properties thus extracted are effective in the sense that they convey optical activity only along crystal axes probed by the incident electric field. However, because near-fields from the probe in the vicinity of the sample are predominantly surface-normal polarized, crystal axes are probed to varying degree, resulting in near-field spectra that reveal all infrared-active vibrational modes possessing a dipole moment perpendicular to the surface64. This raises the possibility that ‘missing’ absorption peaks in κ(ω) could potentially hinder direct comparison to conventional absorption spectra, although this difficulty was not encountered throughout this study.

Sample preparation

We prepared a freshly exposed sample of the Murchison meteorite, a primitive CM2 chondrite, by cleaving an ~5-mm-sized chunk from a much larger piece of Murchison. This fresh chunk was placed at the bottom of a cylindrical mould and embedded in resin (Epo-Fix, Electron Microscopy Sciences). After curing for 24 h, the epoxy cylinder with the Murchison sample was polished using an optical polisher until a region of the sample was exposed. A qualitative determination of optical flatness was achieved by polishing with poly-diamond abrasives, with the final sub-micron polish step performed by hand on a velvet cloth. The sample’s flatness was confirmed by briefly imaging in a Tescan Vega 3 SEM and through AFM in the s-SNOM apparatus.

Samples of cometary dust grains from Comet 81P/Wild 2 (Wild 2), captured in a nano-porous silica aerogel by the Stardust mission (1), were extracted and prepared for laboratory analysis using standard techniques65. A notable Stardust particle named Iris (from track C2052,12,74) has been analyzed with a variety of techniques including Scanning Transmission X-ray Microscopy and TEM33. Using the nanoFTIR set-up that was described previously, we present the first sub-micron IR spectral maps of a cometary sample.

TEM analysis

Murchison line scan 3 (Figs 3d and 5) was verified by S/TEM. After nanoFTIR measurements, a lamella was removed from the meteorite using focused ion beam milling and examined by TEM at the National Center for Electron Microscopy. The lamella exactly traced the nanoFTIR path so that the IR spectrum at each point might be directly compared with TEM imaging, diffraction and EDS composition. Diffraction and imaging in brightfield and darkfield were carried out using a Zeiss Libra 200 MC at 200 keV with an in-column Omega energy filter. With the energy filter, ΔE was ~10 eV centred around the zero-loss peak. STEM/EDS was carried out using a Phillips CM200 with an Oxford Inca Si(Li) energy-dispersive detector.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Dominguez, G. et al. Nanoscale infrared spectroscopy as a non-destructive probe of extraterrestrial samples. Nat. Commun. 5:5445 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6445 (2014).

References

Brownlee, D. et al. Comet 81P/Wild 2 under a microscope. Science 314, 1711–1716 (2006).

Sandford, S. A. et al. Organics captured from Comet 81P/Wild 2 by the Stardust Spacecraft. Science 314, 1720–1724 (2006).

McKeegan, K. D. et al. Isotopic compositions of cometary matter returned by Stardust. Science 314, 1724–1728 (2006).

Keller, L. P. et al. Infrared spectroscopy of Comet 81P/Wild 2 samples returned by Stardust. Science 314, 1728–1731 (2006).

Flynn, G. J. et al. Elemental compositions of Comet 81P/Wild 2 samples collected by Stardust. Science 314, 1731–1735 (2006).

Zolensky, M. E. et al. Mineralogy and petrology of Comet 81P/Wild 2 nucleus samples. Science 314, 1735–1739 (2006).

Maras, A. et al. In situ synchrotron infrared reflectance study of olivine microcrystals in meteorite matrices. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 36, A121 (2001).

Cooney, T. F., Scott, E. R. D., Krot, A. N., Sharma, S. K. & Yamaguchi, A. Vibrational spectroscopic study of minerals in the Martian meteorite ALH84001. Am. Mineral. 84, 1569–1576 (1999).

Keller, L. P. et al. Sulfides in interplanetary dust particles: a possible match to the 23 μm feature detected by the Infrared Space Observatory. Lun. Plan. Sci. 31, 1860 (2000).

Raynal, P. I. et al. Synchrotron infrared microscopy of micron-sized extraterrestrial grains. Planet. Space Sci. 48, 1329–1339 (2000).

Keller, L. P. et al. Identification of iron sulphide grains in protoplanetary disks. Nature 417, 148–150 (2002).

Keller, L. P. et al. The nature of molecular cloud material in interplanetary dust. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68, 2577–2589 (2004).

Morlok, A., Jones, G. C., Grady, M. M. & Stansbery, E. FT-IR micro-spectroscopy of fine-grained planetary materials: further results. Lun. Plan. Sci. 35, 1622 (2004).

Matrajt, G. et al. FTIR and Raman analyses of the Tagish Lake meteorite: relationship with the aliphatic hydrocarbons observed in the diffuse interstellar medium. Astron. Astrophys. 416, 983–990 (2004).

Matrajt, G. et al. FTIR analysis of the organics in IDPs: comparison with the IR spectra of the diffuse interstellar medium. Astron. Astrophys. 433, 979–995 (2005).

Flynn, G. J., Keller, L. P., Feser, M., Wirick, S. & Jacobsen, C. The origin of organic matter in the solar system: evidence from the interplanetary dust particles. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 4791–4806 (2003).

Knoll, B. & Keilmann, F. Near-field probing of vibrational absorption for chemical microscopy. Nature 399, 134–137 (1999).

Taubner, T., Hillenbrand, R. & Keilmann, F. Nanoscale polymer recognition by spectral signature in scattering infrared near-field microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 5064–5066 (2004).

Fei, Z. et al. Infrared nanoscopy of dirac plasmons at the graphene–SiO2 interface. Nano Lett. 11, 4701–4705 (2011).

Fei, Z. et al. Gate-tuning of graphene plasmons revealed by infrared nano-imaging. Nature 487, 82–85 (2012).

Qazilbash, M. M. et al. Mott transition in VO2 revealed by infrared spectroscopy and nano-imaging. Science 318, 1750–1753 (2007).

Jones, A. C., Berweger, S., Wei, J., Cobden, D. & Raschke, M. B. Nano-optical investigations of the metal-insulator phase behavior of individual VO2 microcrystals. Nano Lett. 10, 1574–1581 (2010).

Atkin, J. M., Berweger, S., Jones, A. C. & Raschke, M. B. Nano-optical imaging and spectroscopy of order, phases, and domains in complex solids. Adv. Phys. 61, 745–842 (2012).

Chen, J. et al. Optical nano-imaging of gate-tunable graphene plasmons. Nature 487, 77–81 (2012).

Zhang, L. M. et al. Near-field spectroscopy of silicon dioxide thin films. Phys. Rev. B 85, 075419 (2012).

Amarie, S., Ganz, T. & Keilmann, F. Mid-infrared near-field spectroscopy. Opt. Express 17, 21794–21801 (2009).

Huth, F. et al. Nano-FTIR absorption spectroscopy of molecular fingerprints at 20 nm spatial resolution. Nano Lett. 12, 3973–3978 (2012).

Amarie, S. & Keilmann, F. Broadband-infrared assessment of phonon resonance in scattering-type near-field microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 83, 045404 (2011).

Govyadinov, A. A., Amenabar, I., Huth, F., Carney, P. S. & Hillenbrand, R. Quantitative measurement of local infrared absorption and dielectric function with tip-enhanced near-field microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 1526–1531 (2013).

Amarie, S. et al. Nano-FTIR chemical mapping of minerals in biological materials. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 3, 312–323 (2012).

Dai, S. et al. Tunable phonon polaritons in atomically thin van der Waals crystals of boron nitride. Science 343, 1125–1129 (2014).

Kebukawa, Y. et al. Spatial distribution of organic matter in the Bells CM2 chondrite using near-field infrared microspectroscopy. Meteoritics 45, 394–405 (2010).

Ogliore, R. C. et al. Incorporation of a late-forming chondrule into Comet Wild 2. Astrophys Lett. 745, L19 (2012).

Nakamura, T. et al. Chondrulelike objects in short-period Comet 81P/Wild 2. Science 321, 1664–1667 (2008).

Keilmann, F. & Hillenbrand, R. inNano-Optics and Near-Field Optical Microscopy eds Zayats A., Richards D. 235–265Artech House (2009).

Cvitkovic, A., Ocelic, N. & Hillenbrand, R. Analytical Model for Quantitative Prediction of Material Contrasts in Scattering-Type Near-Field Optical Microscopy. Optics Express 15, 8550–8565 (2007).

McLeod, A. S. et al. Model for quantitative near-field spectroscopy and the extraction of nanoscale-resolved optical constants. Phys. Rev. B 90, 085136 (2014).

Hillenbrand, R., Taubner, T. & Keilmann, F. Phonon-enhanced light-matter interaction at the nanometre scale. Nature 418, 159–162 (2002).

Ocelic, N., Huber, A. & Hillenbrand, R. Pseudoheterodyne detection for background-free near-field spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 101124 (2006).

Glotch, T. D. & Rossman, G. R. Mid-infrared reflectance spectra and optical constants of six iron oxide/oxyhydroxide phases. Icarus 204, 663–671 (2009).

Alonso-González, P. et al. Experimental verification of the spectral shift between near- and far-field peak intensities of plasmonic infrared nanoantennas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 203902 (2013).

Prior, D., Mariani, E. & Wheeler, J. inElectron Backscatter Diffraction in Materials Science eds Schwartz A. J., Kumar M., Adams B. L., Field D. P. 345–360Springer (2009).

Holman, H. Y. N., Martin, M. C. & McKinney, W. R. Synchrotron-based FTIR spectromicroscopy: cytotoxicity and heating considerations. J. Biol. Phys. 29, 275–286 (2003).

Stiegler, J. M., Tena-Zaera, R., Idigoras, O., Chuvilin, A. & Hillenbrand, R. Correlative infrared–electron nanoscopy reveals the local structure–conductivity relationship in zinc oxide nanowires. Nat. Commun. 3, 1131 (2012).

Demichelis, R. et al. The infrared spectrum of ortho-enstatite from reflectance experiments and first-principle simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 420, 147–154 (2012).

Chihara, H., Koike, C., Tsuchiyama, A., Tachibana, S. & Sakamoto, D. Compositional dependence of infrared absorption spectra of crystalline silicates. I. Mg-Fe pyroxenes. Astron. Astrophys. 391, 267–273 (2002).

Dowty, E. & Clark, J. R. Crystal structure refinement and optical properties of a Ti3+ fassaite from the Allende meteorite. Am. Mineral. 58, 230–242 (1973).

Simon, S. B. & Grossman, L. A comparative study of melilite and fassaite in types B1 and B2 refractory inclusions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 780–798 (2006).

Koike, C. et al. Absorption spectra of Mg-rich Mg-Fe and Ca pyroxenes in the mid- and far-infrared regions. Astron. Astrophys. 363, 1115–1122 (2000).

Morimoto, N. et al. Nomenclature of pyroxenes. Am. Mineral. 73, 1123–1133 (1988).

Leroux, H. Microstructural shock signatures of major minerals in meteorites. Eur. J. Mineral. 13, 253–272 (2001).

Downs, R. T. Program and Astracts of the 19th General Meeting of the International Mineralogical Association, O03–O13 (Kobe, Japan, 2006).

Nakamura, M., Kanzawa, R. & Sakai, K. Stress and density effects on infrared absorption spectra of silicate glass films. J. Electrochem. Soc. 133, 1167–1171 (1986).

Zhang, M. et al. Exsolution and Al-Si disorder in alkali feldspars; their analysis by infrared spectroscopy. Am. Mineral. 82, 849–857 (1997).

Balan, E. et al. Line-broadening effects in the powder infrared spectrum of apatite. Phys. Chem. Minerals 38, 111–122 (2011).

Ruppin, R. & Englman, R. Optical phonons of small crystals. Rep. Prog. Phys. 33, 149 (1970).

Genzel, L. & Martin, T. P. Infrared absorption by surface phonons and surface plasmons in small crystals. Surf. Sci. 34, 33–49 (1973).

Day, D. E. & Rindone, G. E. Properties of soda aluminosilicate glasses: I, refractive index, density, molar refractivity, and infrared absorption spectra. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 45, 489–496 (1962).

Roy, B. N. Infrared spectroscopy of lead and alkaline-earth aluminosilicate glasses. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 73, 846–855 (1990).

Fernandez, J. A. & Jockers, K. Nature and origin of comets. Rep. Prog. Phys. 46, 665 (1983).

Nakamura, T. et al. Itokawa dust particles: a direct link between S-type asteroids and ordinary chondrites. Science 333, 1113–1116 (2011).

Rietmeijer, F. J. M. Interplanetary dust particles. Rev. Mineral Geochem. 36, 2.1–2.95 (1998).

Keilmann, F. & Amarie, S. Mid-infrared frequency comb spanning an octave based on an Er fiber laser and difference-frequency generation. J. Infrared Milli. Terahz Waves 33, 479–484 (2012).

Amenabar, I. et al. Structural analysis and mapping of individual protein complexes by infrared nanospectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 4, 2890 (2013).

Westphal, A. J. et al. Aerogel keystones: Extraction of complete hypervelocity impact events from aerogel collectors. Meteoritics 39, 1375–1386 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This work and G.D. were supported by NASA’s Laboratory Analysis of Returned Samples program (# NNX11AF24G). The Advanced Light Source and National Center for Electron Microscopy is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the US Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. A.S.M acknowledges the support from a US Department of Energy Office of Science graduate research fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.D developed the concept of nano-scale IR s-SNOM characterization of extraterrestrial samples and G.D., A.S.M., Z.G., M.T., and D.N.B. conceived and designed the experiments. A.S.M. performed the s-SNOM imaging and nano-spectroscopy experiments and together with P.K. developed and applied a framework for extraction of nano-scale IR extinction spectra. G.D. and Z.G. polished and mounted the Murchison meteorite sample. Z.G. prepared the Iris cometary grain, prepared the FIB lamella, and characterized both samples by SEM, EDS, and TEM. H.A.B. performed synchrotron-based far-field infrared spectroscopy on the Iris cometary grain. All authors discussed the data. A.S.M. and G.D. wrote the manuscript with support from Z.G. and D.N.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

F.K. is co-founder of Neaspec and Lasnix, producers of the s-SNOM and infrared source used in this study. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-5, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 8744 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dominguez, G., Mcleod, A., Gainsforth, Z. et al. Nanoscale infrared spectroscopy as a non-destructive probe of extraterrestrial samples. Nat Commun 5, 5445 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6445

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6445

This article is cited by

-

Theoretical study of broadband near-field optical spectrum of twisted bilayer graphene

Frontiers of Physics (2022)

-

Nano-FTIR spectroscopic identification of prebiotic carbonyl compounds in Dominion Range 08006 carbonaceous chondrite

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Probing subwavelength in-plane anisotropy with antenna-assisted infrared nano-spectroscopy

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Infrared-spectroscopic, dynamic near-field microscopy of living cells and nanoparticles in water

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

6 nm super-resolution optical transmission and scattering spectroscopic imaging of carbon nanotubes using a nanometer-scale white light source

Nature Communications (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.