Abstract

Recent experiments on ultracold atoms in optical lattices have synthesized a variety of tunable bands with degenerate double-well structures in momentum space. Such degeneracies in the single-particle spectrum strongly enhance quantum fluctuations, and often lead to exotic many-body ground states. Here we consider weakly interacting spinor Bose gases in such bands, and discover a universal quantum ‘order by disorder’ phenomenon which selects a novel superfluid with chiral spin order displaying remarkable properties such as spontaneous spin Hall effect and momentum space antiferromagnetism. For bosons in the excited Dirac band of a hexagonal lattice, such a state supports staggered spin loop currents in real space. We show that Bloch oscillations provide a powerful dynamical route to quantum state preparation of such a chiral spin superfluid. Our predictions can be readily tested in spin-resolved time-of-flight experiments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ability to optically address and manipulate the spin and momentum of electrons in a solid is not only of fundamental importance, as it can lead to novel states of matter with unusual properties and consequent functionalities, but also forms the basis for the fertile fields of spintronics and valleytronics1,2,3. Recent experimental progress in the field of ultracold atomic gases has led to the creation of optical lattices supporting bandstructures with multiple minima (valleys)4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18, and setups which allow for the study of low-dimensional transport phenomena12,19,20,21,22. Experimentally, this valley degeneracy is achieved by considering atoms with Raman induced synthetic spin-orbit coupling4,5,6,8,9,10,23, or by loading atoms in shaken optical lattices13,14, excited optical lattice bands7,11,12,15,24 or engineered π-flux lattices16,17,18. These landmark developments herald the emergence of valleytronics (or atomtronics) for cold atoms, and set the stage for the discovery of novel phases of atomic matter.

The presence of multiple valley and spin degrees of freedom often leads to a large degeneracy of single-particle ground states. When such extensive degeneracies persist at mean-field level, many-body fluctuations have a crucial role in selecting the eventual ground state. Indeed, this is the basis for fascinating phases such as fractional quantum Hall liquids in degenerate Landau levels25, unexpected magnetic orders in quasi-one dimensional bands26,27 and highly entangled quantum spin liquids in frustrated magnets28. In certain systems, fluctuations can select unusual long-range ordered many-body states which have the maximal entropy out of the set of energetically degenerate states, a phenomenon dubbed ‘thermal order by disorder’29,30. On the other hand, at low temperatures, the selection may favour ordered states with lower quantum zero point fluctuation on top of the mean-field energy, leading to ‘quantum order by disorder’30. However, a direct identification of this phenomenon in solid state systems is often complicated by the presence of ordinarily negligible and material-specific terms in the Hamiltonian, which can overwhelm the order-by-disorder physics. Ultracold atoms, with clean and well-characterized tunable Hamiltonians, provide a particularly attractive platform to expose this remarkable phenomenon.

Single species of repulsive bosons loaded into a multivalley dispersion will typically condense at a single minimum due to mean-field interactions. This spontaneously broken valley symmetry concurrently leads to a broken inversion and time-reversal symmetry (TRS). Such a condensate in a π-flux triangular lattice yields staggered charge loop current order on triangular plaquettes18,31,32,33,34,35. For weak interactions, the physics of this state is well captured by Gross–Pitaevskii theory36. Analogues of such double-valley condensation of single-component bosons may be realized for magnons in magnetic insulators37,38 and pumped exciton-polaritons in quantum wells39. By contrast, as we show here, the physics of multi-component bosons loaded into such bands is far richer, due to an extra spin-valley degeneracy, which persists even at the classical interacting level so that quantum fluctuations have a crucial role in selecting the eventual ground state.

Here we study two-component or equivalently pseudo-spin-1/2 bosons loaded into a multivalley band. This produces an extra spin-valley degeneracy, since each spin state can be localized in one of two valleys. We show that quantum fluctuations lead to a ‘quantum order by disorder’ effect in such a system, where opposite spins condense at the two minima, giving rise to chiral spin order in the system. Remarkably, this selection is ‘universal’, in that it is independent of the microscopic details, such as the lattice geometry or the precise dispersion, and is guaranteed by the symmetry which protects the valley degeneracy. The most direct experimental consequence of this chiral spin order is ∫ddkk[n↑(k)−n↓(k)]≠0, while ∫ddk[n↑(k)−n↓(k)]=0, where n↑/↓(k) is the spin-resolved momentum distribution. The emergent coupling between spin and orbital motions leads to an interaction-induced spontaneous spin Hall effect of bosons in optical lattices lacking inversion symmetry.

Taking a concrete example of spinor bosons loaded at massive Dirac points of a graphene-like lattice, such as that recently realized experimentally11, we predict that chiral spin order implies spin loop currents in real space. With increasing interaction strength, we find a rich phase diagram, with phase transitions between partially and fully polarized superfluid phases and Mott insulating phases separated by an emergent quantum tricritical point. We show that Bloch oscillation techniques provide a high fidelity route to preparing the chiral spin superfluid and studying the concomitant bosonic spin Hall phenomena.

Results

Emergence of chiral spin order

We first illustrate a minimal model which supports a chiral superfluid ground state. We consider two-component pseudo-spin-1/2 bosons in a spin-independent optical lattice, described by the Hamiltonian H=H0+Hint, with

where φσ x is the lattice annihilation operator with its Fourier transform φσ(k)=∑xφσ xe−ik·x,ε(k) is the energy dispersion, which is identical for both spin ↑ and ↓, μσ is the chemical potential, and Uσ,x;σ′,x' is the density–density interaction. Our treatment in the following is valid in spatial dimensions d=2 or 3. We study a situation where the single-particle dispersion ε(k) possesses two minima, at generically incommensurate wave-vectors ±K related by TRS. Note that TRS here refers to an anti-unitary symmetry Tφσ(k)T−1=φσ(−k), under which the spin is left unchanged, and the dispersion for such a system obeys ε(k)=ε(−k). This is because ‘spin’ in our case simply refers to distinct hyperfine states of an atom. Throughout, we will set ε(±K)=0 as the energy reference point. In the presence of translational symmetry, interactions preserve lattice momentum, and the coupling constant in momentum space reads Uσσ′(q)=∑rUσ,x;σ′,x+reiq˙r.

For weak interactions, the bosons condense at the two minima at ±K, and the condensate wavefunction takes the form:

Here ρ±,σ refers to the density of each spin component at the ±K valleys, and θ±,σ phases of the spin component σ at the two valleys. For single species bosons with short-ranged repulsion, the coexistence of +K and −K costs exchange interaction (Uσσ(2K)>0), so a single-valley condensation associated with the spontaneous breaking of valley symmetry is energetically favoured. In the two-component case we study, this exchange mechanism implies that ρ+,↑ρ−,↑=ρ+,↓ρ−,↓=0, provided |U↑↓(2K)|<(U↑↑(2K)U↓↓(2K))1/2, a condition which is easily satisfied for weakly interacting repulsive spinor bosons (for example the mF=±1 hyperfine states of 23Na (ref. 40)). For contact interactions, this criterion reduces to the familiar criterion for a miscible (spin mixed) phase in real space36.

Therefore at the mean-field level, each component condenses at a single momentum (either +K or −K), yielding four degenerate choices for the condensate wavefunction  : (++)≡(eiK˙r, eiK˙r), (+−)≡(eiK˙r, e−iK˙r), (−−)≡(e−iK˙r, e−iK˙r), and (−+)≡(e−iK˙r, eiK˙r). The degeneracy of (++) with (−−) [or (+−) with (−+)] is guaranteed by TRS. However the degeneracy of (++) with (+−) is due to an accidental symmetry in the mean-field energy,

: (++)≡(eiK˙r, eiK˙r), (+−)≡(eiK˙r, e−iK˙r), (−−)≡(e−iK˙r, e−iK˙r), and (−+)≡(e−iK˙r, eiK˙r). The degeneracy of (++) with (−−) [or (+−) with (−+)] is guaranteed by TRS. However the degeneracy of (++) with (+−) is due to an accidental symmetry in the mean-field energy,

with  , resulting from the density–density nature of interactions, which conserve the populations of each of the two spin components separately. In the (++) or (−−) state, we have chiral charge (χc) order ∫ddk/(2π)dk‹Φ†(k)Φ(k)›≠0, with Φ=(φ↑ ,φ↓)T, while in the (+−) or (−+) state, we have chiral spin (χs) order ∫ddk/(2π)dk‹Φ†(k)σzΦ(k)›≠0. In ultracold atom experiments, chiral spin and charge orders can be distinguished by spin-resolved, time-of-flight measurements11,41.

, resulting from the density–density nature of interactions, which conserve the populations of each of the two spin components separately. In the (++) or (−−) state, we have chiral charge (χc) order ∫ddk/(2π)dk‹Φ†(k)Φ(k)›≠0, with Φ=(φ↑ ,φ↓)T, while in the (+−) or (−+) state, we have chiral spin (χs) order ∫ddk/(2π)dk‹Φ†(k)σzΦ(k)›≠0. In ultracold atom experiments, chiral spin and charge orders can be distinguished by spin-resolved, time-of-flight measurements11,41.

In the asymptotically weak interaction limit, only the minimal momentum points ±K can be populated in the ground state, and the classical degeneracy is exact. We now investigate how quantum fluctuations lift this degeneracy through an ‘order by disorder’ mechanism. To capture fluctuation effects, we start with a heuristic argument on the basis of second order perturbation theory. The dominant inter-spin scattering processes which lower the mean-field energy for the (++) and (+−) (or equivalently the (−−) and (−+)) states at second order are shown in Fig. 1. Physically these processes correspond to annihilating two condensate atoms in opposite spin states and creating two non-condensed atoms. For the chiral charge state, the two processes shown yield the same energy contribution, and give rise to the first term in the right hand side of equation (4). By contrast, for the chiral spin state, the two processes produce different energy contributions, given by the second and third terms in the right hand side of equation (4).

In the chiral spin state ( +−), two condensate atoms of opposite spin at K and −K are scattered to k and −k (or 2K−k and k−2K). In the chiral charge state, atoms of opposite spin at K and K are scattered to k and 2K−k. Here the solid (dashed) arrows denote ↑ (↓), and the red/blue colours differentiate between the two processes, which must be added symmetrically for every k.

Treating these processes perturbatively, the resulting energy difference between the chiral spin and charge states  is readily found by integrating over momentum:

is readily found by integrating over momentum:

with Q=2K, Ns the total number of lattice sites, and the integral excludes the momentum k=±K points. Using ε(k)=ε(−k), it follows from the relation X−1+Y−1≥4(X+Y)−1 (for positive numbers X and Y) that ΔE(2)>0, a remarkably universal result which is independent of the lattice geometry or details of the bandstructure. The chiral spin ordered superfluid state is generically selected, and this energetic selection rule is enforced by TRS.

While the above argument is illuminating, and captures the essential physics, a subtle issue arises in two dimensions, because the integral in equation (4) is logarithmically divergent (from the integral ∫d2k/k2). Thus we need to go beyond the Rayleigh–Schrödinger type bare perturbation theory, and perform a careful Bogoliubov theory analysis (akin to a renormalized Wigner–Brillouin type perturbation theory), to regularize the logarithmic divergence. In the renormalized theory (see Methods and Supplementary Notes 1 and 2), the bare dispersions in equation (4) are replaced by Bogoliubov energy dispersions, and the interaction U↑↓ replaced by effective couplings between the Bogoliubov quasiparticles. This cures the logarithmic divergence, since Bogoliubov spectra appearing in the denominators are linear in momentum near the condensate points. This improved analysis still yields the same robust universal result, ΔE(2)>0, that is, chiral spin order is generically favoured over chiral charge ordering. Note that, this chiral spin order of two-component Bose superfluids in multivalley bands, is distinct from the ‘spin superfluidity’ proposed in fermionic 3He.

In three dimensions, the superfluid transition temperature of the chiral spin state is the non-interacting Bose–Einstein condensate (BEC) temperature (see Methods). In two dimensions, phase fluctuations dominate, and the superfluid transition temperature is determined by vortex proliferation associated with a Kosterlitz–Thouless (KT) transition at Tc≈πG1/2ρσ/8, with G being the curvature of the bandstructure at K (see Methods), which determines the energy costs for phase twists. The chiral spin superfluid also breaks discrete Z2 symmetry, which is expected to be restored at a higher transition temperature42, giving rise to a rich finite temperature phase diagram, with an intermediate non-condensed chiral spin fluid phase, separating the fully disordered and chiral spin superfluid phases. It is worth noting that the superfluid transition temperature is high, comparable to ordinary BEC transition temperature, even though the quantum fluctuation induced energy-density splitting, ΔE(2)/Ns, is small.

Since the two spin components condense at opposite finite momenta in the chiral spin superfluid, the generic feature for this order is ∫ddkk[n↑(k)−n↓(k)]≠0, which can be probed by spin-resolved time-of-flight measurements. Furthermore, when the Hamiltonian has TRS but no inversion symmetry, the chiral spin superfluid exhibits a spontaneous spin Hall effect, which is captured by the response to an applied linear potential (or a constant force F),

where rs is the vector connecting the charge centres of the two spin components, and  is the Berry curvature43. We trace this to the underlying valley-dependent Berry curvature of the single-particle bands, which makes itself manifest as a macroscopic spin Hall effect, in the presence of chiral spin order. In the interacting superfluid, this spin Hall effect only develops below the Ising transition associated with chiral order, and its sign fluctuates depending on the choice of the two Ising states, a spontaneously broken symmetry. Observing a chiral spin superfluid with these novel properties would constitute a direct demonstration of ‘quantum order by disorder’, a quantum fluctuation effect beyond the conventional mean-field theories used to describe Bose–Einstein condensation.

is the Berry curvature43. We trace this to the underlying valley-dependent Berry curvature of the single-particle bands, which makes itself manifest as a macroscopic spin Hall effect, in the presence of chiral spin order. In the interacting superfluid, this spin Hall effect only develops below the Ising transition associated with chiral order, and its sign fluctuates depending on the choice of the two Ising states, a spontaneously broken symmetry. Observing a chiral spin superfluid with these novel properties would constitute a direct demonstration of ‘quantum order by disorder’, a quantum fluctuation effect beyond the conventional mean-field theories used to describe Bose–Einstein condensation.

Spinor condensate at Dirac points

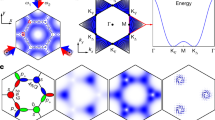

We now consider a concrete model which exhibits the chiral superfluid ground state, and the associated spin Hall effect: bosonic atoms loaded at the massive Dirac points of a spin-dependent honeycomb lattice, as shown in Fig. 2a. Our choice is motivated by recent experiments, where two species of bosonic atoms were loaded into the ground band of such a honeycomb lattice11.

(a) The lattice structure. Spin ↑ (↓) bosons mainly live on A (B) sites. (b) The condensate configuration for the chiral spin superfluid. Spin ↑ and ↓ condensing at +K and −K in the first excited band corresponds to spin loop currents in real space, as illustrated by dashed arrows in a. (c) A contour plot of the excited band Wannier function of spin ↑, which is peaked at the A sites and has a minimum at the B sites (the opposite is true for the spin ↓ Wannier function).

The optical potential of the spin-dependent lattice is11

with bj=0,1,2=(−sin (2πj/3), cos (2πj/3)). We set the lattice constant as the length unit. For  , this potential has inversion symmetry, that is,

, this potential has inversion symmetry, that is,  , and the realized hexagonal lattice has the bandstructure of graphene, two lowest bands touching at the Dirac points. With

, and the realized hexagonal lattice has the bandstructure of graphene, two lowest bands touching at the Dirac points. With  , inversion symmetry is broken, and a gap opens at the Dirac points (akin to the bandstructure of boron nitride44). The first excited band has minima at two Dirac points (Fig. 2b), related by TRS. The model still has a combined spin-space inversion symmetry, namely

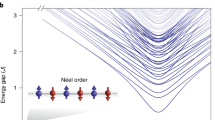

, inversion symmetry is broken, and a gap opens at the Dirac points (akin to the bandstructure of boron nitride44). The first excited band has minima at two Dirac points (Fig. 2b), related by TRS. The model still has a combined spin-space inversion symmetry, namely  which implies that (k)=(−k). Using mF=1 and −1 for pseudo-spin ↑ and ↓, the combined symmetry, together with our defined TRS which relates k to −k (while keeping the pseudo-spin degree of freedom unchanged), guarantees that the two spin components possess the same energy dispersion ε(k) (see the band structure in Supplementary Fig. 1). Therefore, our general theory directly applies to this spin-dependent lattice Hamiltonian. The energy splitting of chiral charge and spin states is shown in Fig. 3a. We predict that the chiral spin superfluid state is the ground state for weakly interacting bosons loaded into the excited band of this lattice (see Fig. 4).

which implies that (k)=(−k). Using mF=1 and −1 for pseudo-spin ↑ and ↓, the combined symmetry, together with our defined TRS which relates k to −k (while keeping the pseudo-spin degree of freedom unchanged), guarantees that the two spin components possess the same energy dispersion ε(k) (see the band structure in Supplementary Fig. 1). Therefore, our general theory directly applies to this spin-dependent lattice Hamiltonian. The energy splitting of chiral charge and spin states is shown in Fig. 3a. We predict that the chiral spin superfluid state is the ground state for weakly interacting bosons loaded into the excited band of this lattice (see Fig. 4).

(a) The energy difference between chiral charge and spin superfluid states with varying inter-spin interaction V and fixed intra-species interaction U. The red ‘+’ symbols are results calculated by solving the Bogoliubov spectra numerically, and the blue solid line is from a renormalized perturbation theory. See the Methods section for details of the tight-binding Hamiltonian we solve. The intra-spin interaction strength is chosen to be U/teff=1 here. For interaction strength V>Vc≈U/3 (not shown here), the system is in a spin polarized state (see Fig. 4). (b) The dynamics of the charge centres, r↑↓ , of the two spin components with a force F applied in the r‖ direction. The two spins move oppositely in the transverse (r⊥) direction, signifying a spin Hall effect. Here we choose ΔD/t=2 and F/t=0.5 (t and ΔD are nearest neighbour tunnelling and Dirac gap respectively, in the hexagonal lattice.).

(a) The phase diagram parameterized by intra- and inter- spin interactions U and V respectively (see Methods). The total density ρ↑+ρ↓ is fixed to be 1 here. In the weakly interacting limit, the chiral spin (χs) superfluid (SF) has a first-order transition to the fully polarized (FP) superfluid state. A partially polarized (PP) SF state is stabilized for intermediate interactions. This PP SF state is also chiral, namely the two spin components condense in opposite valleys (±K). An FP Mott state appears for stronger interactions. The phase boundaries between these polarized states meet at a quantum tricritical point. (b) The polarization as a function of V for different values of U. (c) Tunability of U/V for 87Rb atoms loaded in the spin-dependent hexagonal lattice, as in the experiment11. The lattice depth is chosen to be 0=2Erec, where Erec is the single photon recoil energy.

The momentum distribution of the chiral spin superfluid state (Fig. 5b) shows a pattern similar to the twisted superfluid reported in the experiment11, but in our case, the condensates are located at the Dirac points, rather than reciprocal lattice vectors, as in the experiment. Further, because of the speciality of Bloch modes at Dirac points, the chiral spin superfluid actually has staggered spin loop currents in real space (Fig. 2a), where spin and orbital motion are spontaneously coupled. In fermionic systems, spin loop current orderings have also been predicted recently, albeit in a more delicate way45,46. On the basis of equation (5), the broken inversion symmetry implies that this chiral spin state exhibits a spin Hall effect, due to the Berry curvature at a massive Dirac point,  . (In condensed matter, this is also known as a ‘valley Hall’ effect2, but in our case, valley and spin degrees of freedom are spontaneously coupled in the chiral spin state, giving rise to a spin Hall effect.) In Fig. 3b, we confirm this effect by direct numerical simulations. With time-dependent Gross–Pitaevskii calculations, we find that spin Hall effect is captured by the semiclassical equation (equation (5)), with its magnitude being weakly interaction-dependent (see Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Furthermore, as we show below, this chiral spin state can be prepared deterministically in experiments, by using Bloch oscillations (see Fig. 5 and Methods).

. (In condensed matter, this is also known as a ‘valley Hall’ effect2, but in our case, valley and spin degrees of freedom are spontaneously coupled in the chiral spin state, giving rise to a spin Hall effect.) In Fig. 3b, we confirm this effect by direct numerical simulations. With time-dependent Gross–Pitaevskii calculations, we find that spin Hall effect is captured by the semiclassical equation (equation (5)), with its magnitude being weakly interaction-dependent (see Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Furthermore, as we show below, this chiral spin state can be prepared deterministically in experiments, by using Bloch oscillations (see Fig. 5 and Methods).

(a) The occupation fraction in the ground and excited bands, ng and ne, obtained by projecting the time-dependent wavefunction to the eigenmodes of H2band (see Methods). The time unit is TDirac≈4πℏ/(3λ). (b) The difference between the momentum distributions of the two spin components n↑(k)−n↓(k) in the excited band at time TDirac. In our simulation, we choose ΔD=3t and λ=0.2t. The spread of the momentum distribution difference over a finite momentum range is due to the harmonic trap.

To study phase transitions from the weakly interacting chiral spin superfluid, we project into the second band, which is valid when the band gap ΔD dominates over other energy scales, such as effective tunnelling teff in the second band, and the intra- and inter-species interactions U and V (see Methods.) The Wannier orbitals for the spin ↑ and ↓ atoms in the resulting single-band Hamiltonian (see Methods) are shown in Fig. 2c. We study the properties of this tight-binding Hamiltonian using Gutzwiller mean-field theory, which predicts the correct qualitative phase diagram in d=2,3. When V is strong, the chiral superfluid is unstable towards phase separation into fully polarized domains. In the weakly interacting limit, this transition is first order, and occurs at a critical interaction strength Vc=U/3 (ref. 36). In the strongly interacting limit U→∞, there is also a direct first-order transition to a fully polarized state, but at a different critical value Vc=2teff (see Supplementary Note 4). For intermediate interactions, that is, when U and V are not too large, correlation effects stabilize a partially polarized chiral spin superfluid state. The transitions out of this intermediate state are second order (Fig. 4). With the density fixed at ρ↑+ρ↓=1, we find a novel quantum tricritical point at the crossing of the phase boundaries between the polarized superfluid and Mott phases.

Discussion

From our analysis, the chiral spin superfluid is a generic state for spinor bosons loaded into a double-well energy band, connected by TRS. This state thus not only exists in the hexagonal lattice11,12 example we study, but also in a π-flux triangular lattice14, a shaken lattice13 and other similar Bose systems. The observable signature for chiral spin order, expected to emerge in all these setups, is ∫ddkk[n↑(k)−n↓(k)]≠0. In the shaken lattice setup recently realized in Chicago13, the chiral spin state produces a time-of-flight signal similar to that in spin-orbit coupled gases6, but with a spontaneously chosen sign for the spin-orbit coupling, which will vary from shot to shot. In optical lattices with broken inversion symmetry, this chiral spin superfluid supports a spontaneous spin Hall effect. The required potential gradient to observe this transport phenomenon is different in spin-independent and spin-dependent lattices. In the former13,12, a spin-independent force (or non-magnetic potential gradient) is sufficient, whereas in the latter case11, a spin-dependent force mFF (or a magnetic potential gradient) is necessary to accommodate for the spin-dependence of the lattice.

The idea that the chiral spin order is selected due to time-reversal invariance can be generalized to more general bands with multi-minima respecting crystalline symmetries, where the nature of momentum space magnetism is expected to be richer. Such multiple minimum bands are believed to occur in high spin systems, such as Dysprosium or Erbium atoms coupled to Raman fields47. In addition to the motivation from optical lattices11,13,14, the proposed momentum space magnetism is also potentially relevant to spontaneous vortex formation in BECs confined in ring geometries48.

Finally, we note that if the TRS is weakly broken, the chiral spin order would no longer be generically stable. We expect a phase transition from the chiral spin to the chiral charge superfluid, once the energy difference, ε(K)−ε(−K) dominates over the quantum fluctuation correction (equation (4) and Fig. 3). We however emphasize here that TRS is usually respected in optical lattices in the absence of artificial gauge fields23.

Methods

Regularization of the logarithmic divergence

To treat the logarithmic divergence in the bare perturbation theory (equation (4)) in two dimensions, we perform a more careful analysis using Bogoliubov theory, and find the energy difference between chiral spin and charge states to be (see Supplementary Notes 1 and 2)

where

,

,  , and

, and  , and the effective couplings g are given in Supplementary Note 1. Following the same arguments as the bare perturbation theory, we recover ΔE(2)>0. Therefore, the chiral spin superfluid is generically favoured over the chiral charge superfluid, in the presence of unbroken TRS symmetry.

, and the effective couplings g are given in Supplementary Note 1. Following the same arguments as the bare perturbation theory, we recover ΔE(2)>0. Therefore, the chiral spin superfluid is generically favoured over the chiral charge superfluid, in the presence of unbroken TRS symmetry.

Finite temperature transitions

In three dimensions at low temperature, the chiral spin superfluid state breaks two U(1) symmetries (corresponding to two spins) and a Z2 symmetry (k→−k). For the balanced case, with ρ↑=ρ↓, we expect three nearly coincident transitions (one Ising and two U(1)) near the three dimensional BEC transition temperature, while for the imbalanced case, we expect a U(1) transition for the minority spin at lower temperature, followed by two nearly coincident transitions (Ising and U(1) for the majority spin) at a higher temperature. In two dimensions, the superfluidity transition temperature is determined by phase fluctuations. The fluctuations on top of chiral spin superfluid state are captured by introducing slowly varying fields  as

as  and

and  . The energy cost of these fluctuations is

. The energy cost of these fluctuations is

with Zij=∂ki∂kjε(k)|k→K. Transforming to the coordinate frame with Zij being diagonal and replacing  by

by  , ΔE is rewritten as ΔE=(1)/(2)∫d2x∑σρσ{λ1(∂x1θσ)2+λ2(∂x2θσ)2}, where λ1,2 are eigenvalues of [Z]. The KT transition temperature is then estimated to be Tc≈πG1/2ρσ/8, where G is the Gaussian curvature of the bandstructure at K, which is λ1λ2. For the symmetric case with ρ↑=ρ↓, we have a single KT transition, while for ρ↑≠ρ↓ there are two separate KT transitions at different temperatures. The Ising transition associated with the chiral order is expected to occur slightly above the higher superfluid transition, as observed in other studies of chiral superfluids42. In principle, a chiral spin state which has chiral spin order, but no superfluidity, could occur in a temperature window above superfluid transitions42; the exploration of such a remarkable bosonic chiral spin fluid is left for future studies.

, ΔE is rewritten as ΔE=(1)/(2)∫d2x∑σρσ{λ1(∂x1θσ)2+λ2(∂x2θσ)2}, where λ1,2 are eigenvalues of [Z]. The KT transition temperature is then estimated to be Tc≈πG1/2ρσ/8, where G is the Gaussian curvature of the bandstructure at K, which is λ1λ2. For the symmetric case with ρ↑=ρ↓, we have a single KT transition, while for ρ↑≠ρ↓ there are two separate KT transitions at different temperatures. The Ising transition associated with the chiral order is expected to occur slightly above the higher superfluid transition, as observed in other studies of chiral superfluids42. In principle, a chiral spin state which has chiral spin order, but no superfluidity, could occur in a temperature window above superfluid transitions42; the exploration of such a remarkable bosonic chiral spin fluid is left for future studies.

Experimental preparation of the chiral spin state

Here we propose a deterministic way to prepare the chiral superfluid state with Bloch oscillations. We start with the lowest band condensate in the lattice potential  for which the two lowest bands touch at Dirac points. Applying a magnetic potential gradient −mFλx, the spin ↑ and ↓ components will move toward the Dirac points at K and −K, respectively. At time TDirac≈(4πℏ)/(3λ), the components reach the respective Dirac points, after which we quickly ramp up the spin-dependent potential (the term proportional to

for which the two lowest bands touch at Dirac points. Applying a magnetic potential gradient −mFλx, the spin ↑ and ↓ components will move toward the Dirac points at K and −K, respectively. At time TDirac≈(4πℏ)/(3λ), the components reach the respective Dirac points, after which we quickly ramp up the spin-dependent potential (the term proportional to  in equation (6)), to make the Dirac points massive with a band gap ΔD. With ΔD much larger than the bandwidth and interactions, the inter-band dynamics will be strongly suppressed. The meta-stable state in the excited band is given by an effective single-band Hamiltonian, described in the next paragraph. To demonstrate the efficiency of the proposed procedure, we simulate the Bloch oscillations by taking a two-band tight-binding model of free bosons,

in equation (6)), to make the Dirac points massive with a band gap ΔD. With ΔD much larger than the bandwidth and interactions, the inter-band dynamics will be strongly suppressed. The meta-stable state in the excited band is given by an effective single-band Hamiltonian, described in the next paragraph. To demonstrate the efficiency of the proposed procedure, we simulate the Bloch oscillations by taking a two-band tight-binding model of free bosons,

and the magnetic potential gradient is modelled as

where A and B label the two sublattices as shown in Fig. 2. We find that the occupation fraction of the excited band could easily reach 50% (Fig. 5). The prepared momentum distribution has sharp peaks as required for the chiral spin superfluid. Including the effects of interactions in the dynamics via a Gross–Pitaevskii equation, the achievable transfer fraction to the excited band is lowered somewhat, and the peaks in the momentum distribution broaden (see Supplementary Fig. 3). However these effects are negligible for shallow lattices, where the interactions are weak compared with single-particle tunnelings.

Calculation of the phase diagram

To obtain the phase diagram of the meta-stable states in the second band of the hexagonal lattice, we construct an effective single-band tight-binding model,

Here φσ,r is the annihilation operator for the Wannier functions peaked at position r (Fig. 2), and each spin species sees a triangular lattice. This Bose–Hubbard model describes bosons loaded into the second band of the hexagonal lattice. In this lattice setup, the Wannier functions of ↑ and ↓ components are peaked at two nearby sites rather than on the same one, which makes the ratio of interactions V/U easily tunable. For example, this ratio can be decreased by increasing the lattice depth or the spin-dependence parameter  (see Fig. 4c). The interaction strength U/teff can be tuned by controlling the lattice depth, as already demonstrated by the experimental observation of the superfluid-Mott transition11. The energy dispersion from the tight-binding model is ε(k)=2t∑jcos (k˙Rj), which has band minima at ±K=(±(4π)/(3),0). For weak interactions, the energy difference between the chiral charge and spin states computed from this model is shown in Fig. 3.

(see Fig. 4c). The interaction strength U/teff can be tuned by controlling the lattice depth, as already demonstrated by the experimental observation of the superfluid-Mott transition11. The energy dispersion from the tight-binding model is ε(k)=2t∑jcos (k˙Rj), which has band minima at ±K=(±(4π)/(3),0). For weak interactions, the energy difference between the chiral charge and spin states computed from this model is shown in Fig. 3.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Li, X. et al. Chiral magnetism and spontaneous spin Hall effect of interacting Bose superfluids. Nat. Commun. 5:5174 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6174 (2014).

References

Žutic′, I., Fabian, J. & Das Sarma, S. Spintronics: fundamentals and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 76, 323–410 (2004).

Xiao, D., Yao, W. & Niu, Q. Valley-contrasting physics in graphene: magnetic moment and topological transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 236809 (2007).

Mak, K. F., McGill, K. L., Park, J. & McEuen, P. L. The valley hall effect in MoS2 transistors. Science 344, 1489–1492 (2014).

Higbie, J. & Stamper-Kurn, D. M. Periodically dressed bose-einstein condensate: a superfluid with an anisotropic and variable critical velocity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 090401 (2002).

Lin, Y.-J., Compton, R. L., Jimenez-Garcia, K., Porto, J. V. & Spielman, I. B. Synthetic magnetic fields for ultracold neutral atoms. Nature 462, 628–632 (2009).

Lin, Y.-J., Jimenez-Garcia, K. & Spielman, I. B. Spin-orbit-coupled bose-einstein condensates. Nature 471, 83–86 (2011).

Wirth, G., Olschlager, M. & Hemmerich, A. Evidence for orbital superfluidity in the p-band of a bipartite optical square lattice. Nat. Phys. 7, 147–153 (2011).

Zhang, J.-Y. et al. Collective dipole oscillations of a spin-orbit coupled bose-einstein condensate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 115301 (2012).

Wang, P. et al. Spin-orbit coupled degenerate fermi gases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 095301 (2012).

Cheuk, L. W. et al. Spin-injection spectroscopy of a spin-orbit coupled fermi gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 095302 (2012).

Soltan-Panahi, P., Luhmann, D.-S., Struck, J., Windpassinger, P. & Sengstock, K. Quantum phase transition to unconventional multi-orbital superfluidity in optical lattices. Nat. Phys. 8, 71–75 (2012).

Tarruell, L., Greif, D., Uehlinger, T., Jotzu, G. & Esslinger, T. Creating, moving and merging dirac points with a fermi gas in a tunable honeycomb lattice. Nature 483, 302–305 (2012).

Parker, C. V., Ha, L.-C. & Chin, C. Direct observation of effective ferromagnetic domains of cold atoms in a shaken optical lattice. Nat. Phys. 9, 769–774 (2013).

Struck, J. et al. Engineering ising-xy spin-models in a triangular lattice using tunable artificial gauge fields. Nat. Phys. 9, 738–743 (2013).

Ölschläger, M. et al. Interaction-induced chiral p x±ip y superfluid order of bosons in an optical lattice. New J. Phys. 15, 083041 (2013).

Aidelsburger, M. et al. Realization of the hofstadter hamiltonian with ultracold atoms in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 185301 (2013).

Miyake, H., Siviloglou, G. A., Kennedy, C. J., Burton, W. C. & Ketterle, W. Realizing the harper hamiltonian with laser-assisted tunneling in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 185302 (2013).

Atala, M. et al. Observation of chiral currents with ultracold atoms in bosonic ladders. Nat. Phys. 10, 588–593 (2014).

Strohmaier, N. et al. Interaction-controlled transport of an ultracold fermi gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 220601 (2007).

Hazlett, E. L., Ha, L.-C. & Chin, C. Anomalous thermoelectric transport in two-dimensional Bose gas. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1306.4018 (2013).

Beeler, M. C. et al. The spin hall effect in a quantum gas. Nature 498, 201–204 (2013).

Krinner, S., Stadler, D., Husmann, D., Brantut, J.-P. & Esslinger, T. Observation of Quantized Conductance in Neutral Matter. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1404.6400 (2014).

Galitski, V. & Spielman, I. B. Spin-orbit coupling in quantum gases. Nature 494, 49–54 (2013).

Lewenstein, M. & Liu, W. V. Optical lattices: orbital dance. Nat. Phys. 7, 101–103 (2011).

Tsui, D. C., Stormer, H. L. & Gossard, A. C. Two-dimensional magnetotransport in the extreme quantum limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 48, 1559–1562 (1982).

Chen, G. & Balents, L. Ferromagnetism in itinerant two-dimensional t2g systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 206401 (2013).

Li, Y., Lieb, E. H. & Wu, C. Exact results for itinerant ferromagnetism in multiorbital systems on square and cubic lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 217201 (2014).

Balents, L. Spin liquids in frustrated magnets. Nature 464, 199–208 (2010).

Villain, J., Bidaux, R., Carton, J.-P. & Conte, R. Order as an effect of disorder. J. Phys. France 41, 1263–1272 (1980).

Henley, C. L. Ordering due to disorder in a frustrated vector antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 2056–2059 (1989).

Eckardt, A. et al. Frustrated quantum antiferromagnetism with ultracold bosons in a triangular lattice. Europhys. Lett. 89, 10010 (2010).

Dhar, A. et al. Bose-hubbard model in a strong effective magnetic field: Emergence of a chiral mott insulator ground state. Phys. Rev. A 85, 041602 (2012).

You, Y.-Z., Chen, Z., Sun, X.-Q. & Zhai, H. Superfluidity of bosons in kagome lattices with frustration. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 265302 (2012).

Dhar, A. et al. Chiral mott insulator with staggered loop currents in the fully frustrated bose-hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 87, 174501 (2013).

Zaletel, M. P., Parameswaran, S. A., Rüegg, A. & Altman, E. Chiral bosonic mott insulator on the frustrated triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. B 89, 155142 (2014).

Pethick, C. & Smith, H. Bose-Einstein Condensation in Dilute Gases Cambridge Univ. Press (2008).

Demokritov, S. O. et al. Bose-Einstein condensation of quasi-equilibrium magnons at room temperature under pumping. Nature 443, 430–433 (2006).

Giamarchi, T., Ruegg, C. & Tchernyshyov, O. Bose-Einstein condensation in magnetic insulators. Nat. Phys. 4, 198–204 (2008).

Kim, N. Y. et al. Dynamical d-wave condensation of exciton-polaritons in a two-dimensional square-lattice potential. Nat. Phys. 7, 681–686 (2011).

Stenger, J. et al. Spin domains in ground-state bose-einstein condensates. Nature 396, 345–348 (1998).

McKay, D. & DeMarco, B. Thermometry with spin-dependent lattices. New J. Phys. 12, 055013 (2010).

Li, X., Paramekanti, A., Hemmerich, A. & Liu, W. V. Proposed formation and dynamical signature of a chiral bose liquid in an optical lattice. Nat. Commun. 5, 3205 (2014).

Xiao, D., Chang, M.-C. & Niu, Q. Berry phase effects on electronic properties. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1959–2007 (2010).

Rubio, A., Corkill, J. L. & Cohen, M. L. Theory of graphitic boron nitride nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 49, 5081–5084 (1994).

Raghu, S., Qi, X.-L., Honerkamp, C. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological mott insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 156401 (2008).

Goto, S., Masuda, K. & Kurihara, S. Spontaneous loop-spin current with topological characters in the Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 90, 075102 (2014).

Cui, X., Lian, B., Ho, T.-L., Lev, B. L. & Zhai, H. Synthetic gauge field with highly magnetic lanthanide atoms. Phys. Rev. A 88, 011601 (2013).

Liu, G., Snoke, D. W., Daley, A., Pfeiffer, L. & West, K. Spin-Flipping Half Vortex in a Macroscopic Polariton Spinor Ring Condensate. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1402.4339 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank W. Vincent Liu, Di Xiao, Kai Sun, R. G. Hulet, Stefan Baur and D. Snoke for helpful discussions. This work is supported by JQI-NSF-PFC and ARO-Atomtronics-MURI (X.L., S.S.N. and S.D.S.). A.P. acknowledges support from NSERC of Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L. conceived the theoretical ideas and performed the calculations with insightful inputs from S.S.N., A.P. and S.D.S. All authors worked on the theoretical analysis and contributed to the manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-3, Supplementary Notes 1-4 and Supplementary References. (PDF 972 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Natu, S., Paramekanti, A. et al. Chiral magnetism and spontaneous spin Hall effect of interacting Bose superfluids. Nat Commun 5, 5174 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6174

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6174

This article is cited by

-

Long-range non-diffusive spin transfer in a Hall insulator

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Absence of Landau damping in driven three-component Bose–Einstein condensate in optical lattices

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.