Abstract

Knowledge of surface forces is the key to understanding a large number of processes in fields ranging from physics to material science and biology. The most common method to study surfaces is dynamic atomic force microscopy (AFM). Dynamic AFM has been enormously successful in imaging surface topography, even to atomic resolution, but the force between the AFM tip and the surface remains unknown during imaging. Here we present a new approach that combines high-accuracy force measurements and high-resolution scanning. The method, called amplitude-dependence force spectroscopy (ADFS), is based on the amplitude dependence of the cantilever’s response near resonance and allows for separate determination of both conservative and dissipative tip–surface interactions. We use ADFS to quantitatively study and map the nano-mechanical interaction between the AFM tip and heterogeneous polymer surfaces. ADFS is compatible with commercial atomic force microscopes and we anticipate its widespread use in taking AFM toward quantitative microscopy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-quality-factor resonators are increasingly used in a wide variety of ultra-sensitive measurements of force1, mass2 and motion3. High quality factor means that the oscillator can respond with large changes in oscillation amplitude or phase, to very small changes in a perturbing force. The dominant measurement paradigm for exploiting this enhanced sensitivity is based on driving the resonator with one pure tone near its resonance while monitoring the response to the perturbation as a change of amplitude or phase, or even a frequency shift when a feedback loop is used to lock the phase. In the field of atomic force microscopy (AFM), this measurement paradigm has been used to create images of surfaces to atomic resolution4 with very little back-action on soft and delicate material surfaces. However, in spite of its name, the atomic ‘force microscope’ does not actually measure the force between the tip and the surface while imaging in these modalities. The determination of the tip–surface force requires that one monitors the change in response as one slowly changes the height of the resonator above the surface5,6,7,8,9,10. Such measurements have provided impressive three-dimensional force–volume plots11,12, but they are fundamentally limited by extremely long acquisition times that necessitate enormous effort to reduce drift artifacts13, making the three-dimensional force maps impractical for most applications.

In this article we demonstrate a new approach to dynamic interaction measurement based on actively modulating the amplitude of oscillation while measuring the amplitude dependence of the resonators response. A variation of amplitude, which is slow on the time scale of the oscillation period, lends itself to an analysis of the perturbing force in terms of the amplitude dependence of two signals: one in-phase and one quadrature to the sinusoidal motion. The amplitude dependence of these two force signals allows us to determine the tip–surface interaction directly as a function of the cantilever deflection at fixed probe height. We show how these two quadrature force signals provide the foundation for model-free determination of the conservative force versus distance curve, as well as an energy loss versus amplitude curve. These two force signals represent essentially all the information that is possible to obtain about the non-linear perturbing force, from analysis of oscillator motion in the limited frequency band near the high Q resonance. After deriving the theory of amplitude-dependence force spectroscopy (ADFS), we test the concept both with numerical simulation and experimental study of heterogeneous polymer surfaces. The improved force resolution of ADFS allows us to critically analyse a commonly accepted model of the tip–surface interaction and it enables an alternative approach for characterizing the mechanical properties of polymer surfaces.

Results

Dynamics and force modelling

In air and in vacuum, the continuum dynamics of a cantilever beam are usually reduced to a single-mode harmonic oscillator described by a simple equation of motion14

where z is the position of the tip in the lab frame, h corresponds to the static probe height above the surface and  is the frequency of the first flexural cantilever resonance with quality factor Q, effective spring constant k and effective mass m. The two forces acting on the oscillator are the tip–surface force Fts and the external sinusoidal drive force of strength Fdrive. The tip–surface force Fts is, in general, a complicated function depending on the instantaneous tip position z(t), velocity ż(t) and, for hysteretic forces, on the past tip trajectory {z(t)}. One typically decomposes the tip–surface interactions into an effective conservative part, which only depends on the tip position z, and a more complicated effective dissipative part6

is the frequency of the first flexural cantilever resonance with quality factor Q, effective spring constant k and effective mass m. The two forces acting on the oscillator are the tip–surface force Fts and the external sinusoidal drive force of strength Fdrive. The tip–surface force Fts is, in general, a complicated function depending on the instantaneous tip position z(t), velocity ż(t) and, for hysteretic forces, on the past tip trajectory {z(t)}. One typically decomposes the tip–surface interactions into an effective conservative part, which only depends on the tip position z, and a more complicated effective dissipative part6

When driving with a sinusoidal signal on resonance, ωdrive=ω0, the tip motion z(t) is approximately sinusoidal15

with amplitude A, frequency ω0 and phase lag φ, with respect to the drive force, even under the influence of the significant tip–surface interactions. This sinusoidal tip motion is a result of the large quality factor (Q~100 in air, Q~10,000 in vacuum), which guarantees that the energy in the cantilever oscillation is greater than the tip–surface interaction energy during one oscillation cycle.

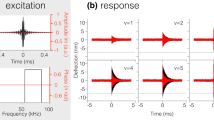

The observation that the tip follows a simple orbit in the z–ż phase plane leads to a more compact description of the tip–surface force. Every point in the phase plane is part of only one sinusoidal orbit with a specific amplitude. Together with the assumption that the tip–surface force does not depend on previous interaction cycles, every point in the phase plane can be mapped to a unique history of the tip motion that starts at the maximum distance from the sample surface during an oscillation cycle. Thus, the dependence of the tip–surface force on the past tip trajectory can be incorporated into the dependence on the tip position z and velocity ż. Therefore, the interaction is completely described as a two-dimensional function in phase space. Such a function is depicted in Fig. 1a. The plotted model force is a van der Waals–Derjaguin–Muller–Toropov force with an additional damping term that depends exponentially on the tip position z. This force model is given by

(a) A model tip–surface force is shown as a function of tip position and velocity. The force is given by equation 4. The zoomed inset shows the region close to the surface where the force is non-zero. The black lines are tip orbits with different amplitudes. The force is only plotted up to the maximum amplitude. (b–e) The corresponding approach retract force curves where the red curve is the force on approach and the blue curve is the force during retract. The curves show a clear amplitude dependence of the dissipated energy. For small amplitudes, the force curve is essentially given by the conservative part of the tip–surface force. For large amplitude, the dissipative interaction dominates and the approach and retract curves change significantly.

where H is the Hamaker constant, R is the tip radius, a0 is the intermolecular distance, γ0 is the damping constant, zγ is the damping decay length, and E* is the effective stiffness of the tip sample system. The assumed numerical values for these constants are shown in Table 1.

Tip motion with fixed amplitude is depicted in Fig. 2a. The corresponding phase space trajectory in Fig. 2b covers only one simple orbit. Thus, force measurement at only one amplitude does not reveal the full nature of the tip–surface interaction as illustrated in Fig. 1b–e, where conventional force–distance curves for different oscillation amplitudes are plotted. It is not possible to extract the exponential dependence of the damping from only one measurement at fixed amplitude. Several measurements with different amplitudes are required to cover a larger region in the phase plane and gain a deeper insight into the nature of the tip–surface force, especially regarding dissipative interactions, which can have very different physical origin.

(a) Tip motion with constant amplitude in the time domain. (b) The constant amplitude trajectory in phase space covers only one orbit and it is not possible to reveal the complex dependence of the force on z and ż. (c) With modulated amplitude, the tip performs a beat-like motion in the time domain. The amplitude modulation is slow compared with the frequency of the tip oscillation. At the lower turning points where the tip interacts with the surface, the motion can be considered purely sinusoidal with constant amplitude. (d) Over a full modulation period, a large area in phase space is covered and the tip experiences the full z- and ż-dependence of the tip–surface force.

Force amplitude dependence

The tip–surface force could be considered as a time-dependent force acting on the oscillator and the force could then be reconstructed from higher harmonics of the tip motion16,17. However, equation 3 implies that higher harmonics of the tip motion are insignificant. Indeed, their amplitudes are typically below the detection noise floor and special force transducers18, high interaction forces16 or highly damped environments19 are required for their measurement. The high-quality factor of the cantilevers resonance amplifies only the Fourier components of the force near the resonance frequency ω0, whereas higher harmonics are sharply attenuated. The force Fourier component  (ω0) can be determined from knowledge of the calibrated cantilever linear response function

(ω0) can be determined from knowledge of the calibrated cantilever linear response function  , the drive force Fdrive and the equation of motion in Fourier space

, the drive force Fdrive and the equation of motion in Fourier space

where  (ω) is the Fourier transform of the tip motion z(t). With equation 3, the complex Fourier component

(ω) is the Fourier transform of the tip motion z(t). With equation 3, the complex Fourier component  (ω0) can also be expressed as two real-valued Fourier components that are in-phase and quadrature to the motion

(ω0) can also be expressed as two real-valued Fourier components that are in-phase and quadrature to the motion

where T=2π/ω0 is the oscillation period. FI and FQ can be measured with high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), providing a foundation for highly accurate force reconstruction. FI and FQ are usually measured for different probe heights h above the surface5,6,7,8,9,10. However, their dependence on oscillation amplitude A can also be used for force reconstruction. Hence, the name ADFS.

The component FI is called the virial of the tip motion and is only affected by conservative tip–surface interactions20. As the conservative tip–surface force Fc depends only on the tip position z, we can rewrite equation 6 as (see Methods)

Equation 8 shows that FI(A) is the Abel integral transform of the conservative part of the tip–surface interaction21. The Abel transform has a unique inverse transform with which we determine the conservative tip–surface force as

Thus, equation 9 enables force reconstruction at fixed static tip sample separation h, using only the oscillation amplitude dependence of FI(A).

For dissipative forces, such a simple reconstruction is not possible, as they also depend on the tip velocity ż. However, the force component FQ(A) can be interpreted as the amplitude-dependent energy loss per oscillation cycle (see Methods)

The amplitude dependence of the energy loss gives a signature of the dissipation mechanism and equation 10 allows for the quantitative exploration of the dissipative interaction at fixed probe height h, whereas previously a slow change of h was required22.

Probing the tip–surface interaction

To rapidly acquire the data for ADFS, we use a multi-frequency lock-in measurement scheme23, which combines the fast tip oscillation at the resonance frequency ω0 of the cantilever with a slowly varying amplitude. Different amplitude modulated drive schemes have been considered before24,25, but they allowed only for a qualitative analysis of the tip–surface interaction. The beat-like tip motion resulting from the drive signal is periodic with the beat frequency Δω (Fig. 2c). The calibrated linear response function  of the cantilever is used to convert the measured tip motion spectrum [zcirc](ω) to the force signals FI and FQ. Because of the slow change of the oscillation amplitude, every oscillation cycle at the fast frequency ω0 can be considered as an oscillation with fixed amplitude. Over a full beat period, a large region in phase space is covered (Fig. 2d), and the complete dependence of FI(A) and FQ(A) on the oscillation amplitude is revealed. The measurement time for complete FI(A) and FQ(A) is 2 ms in our experiments under ambient conditions. This high acquisition speed makes it possible to combine high-resolution surface imaging with high-accuracy force measurements in a single scan with normal scan rates. To minimize feedback artifacts while scanning, we evaluate FI(A) and FQ(A) only while the oscillation amplitude increases.

of the cantilever is used to convert the measured tip motion spectrum [zcirc](ω) to the force signals FI and FQ. Because of the slow change of the oscillation amplitude, every oscillation cycle at the fast frequency ω0 can be considered as an oscillation with fixed amplitude. Over a full beat period, a large region in phase space is covered (Fig. 2d), and the complete dependence of FI(A) and FQ(A) on the oscillation amplitude is revealed. The measurement time for complete FI(A) and FQ(A) is 2 ms in our experiments under ambient conditions. This high acquisition speed makes it possible to combine high-resolution surface imaging with high-accuracy force measurements in a single scan with normal scan rates. To minimize feedback artifacts while scanning, we evaluate FI(A) and FQ(A) only while the oscillation amplitude increases.

Moreover, the high-quality factor resonance guarantees a gradual change of the oscillation amplitude, so that we can determine the tip–surface interaction without deflection or amplitude jumps that are caused by instabilities, which are inherent to quasi-static and other dynamic force spectroscopy methods26. Furthermore, we have not observed any indication of irregular motion or subharmonic generation when we study the tip motion over several beat periods while slowly approaching a polystyrene (PS) surface.

Numerical simulations

We begin with numerical simulations of the equation of motion (1) with the tip–surface force defined by equation 4 and the numerical values for the force constants given in Table 1. We consider a standard cantilever in air with resonance frequency of f0=ω0/(2π)=300 kHz, quality factor of Q=400 and stiffness of k=40 N m−1. We apply a drive force with frequency f0 and sinusoidally modulate the drive strength at a frequency of Δf=500 Hz. Without any tip–surface interaction, this drive force yields a beat-like motion with a maximum amplitude of 25 nm. In the presence of the tip–surface force, we let the system reach a steady state and then collect data during two cycles of the amplitude modulation at a distance of 17 nm above the surface.

From the simulated motion, we extract FI(A) and reconstruct the conservative tip–surface force Fc using equation 9. The reconstructed curve is shown in Fig. 3, and it is in excellent agreement with the actual force used in the simulations. At the sharp transition point from the attractive to the repulsive regime, small deviations become visible in the order of 0.7 nN.

Experimental results under ambient conditions

In material science, often the local mechanical properties of heterogeneous polymer materials are of interest. One example of such a material is a blend of PS and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) with surface topography shown in Fig. 4a. The different solubility of these immiscible polymers causes the formation of domains with different height. The higher structures in Fig. 4a are PMMA-rich, whereas the lower background matrix is PS-rich27. Scanning this sample, we collect data at 1,024 points on each of 256 scan lines in 17 min. Without any additional assumptions about the force or the motion, the conservative force curve is determined using equation 9. A typical conservative force curve at one image pixel is shown in Fig. 4b. The curve shows an attractive force close to the surface with a sharp onset of repulsive force when the tip makes mechanical contact with the surface.

(a) The plateaus of the surface topography have a height of circa 5 nm and are PMMA-rich, whereas the lower regions are PS-rich. (b) Reconstructed conservative force for the position marked with the red point in a. The force has an attractive minimum where the tip makes mechanical contact with the surface. Beyond this contact point the tip indents the surface and experiences a rapidly growing repulsive force. (c) Force reconstruction in all points generates a map of the interaction exponent p defined in equation 11. The map does not show a significant difference between the PS and the PMMA domains. (d) Separate histograms of the interaction exponent for the PS (blue) and PMMA (red) domains. (e) Map of the surface stiffness factor ε defined in equation 11. (f) Separate histograms of the stiffness factor for the PS (blue) and PMMA (red) domains. The PMMA-rich areas are a factor of three stiffer than the PS matrix.

The ability to rapidly measure a conservative force curve with such high accuracy at every image point enables a more detailed study of the local nano-mechanical interaction. In the absence of adhesion, the repulsive conservative force is generally described in terms of a power law of the form28

where ε is the local stiffness factor for a particular interaction geometry and zmin is the position of the force minimum Fmin. To minimize the adhesion during the mechanical contact between the tip and the surface, we use a cantilever with small nominal radius below 10 nm. A fit of the force model to the reconstructed force at every image point reveals that the interaction exponent has a mean value of 2.35±0.3, on both the PS- and PMMA-rich domains (see Fig. 4c). This observation suggests that the geometry of the contact is close to the ideal case of a cone indenting a flat surface, where an exponent of p=2.0 is expected29. We attribute this behaviour to the actual conic shape of the AFM tip. In contrast, traditional quantitative AFM methods assume the Derjaguin–Muller–Toropov model geometry of a perfect sphere indenting a flat surface where an exponent of p=1.5 is expected30. The measured interaction exponent illustrates the difficulties of quantitative parameter extraction from AFM measurements for which common approaches are based on various assumptions about surface adhesion, probe shape and interaction geometry. Furthermore, one should note that the applicability of continuum mechanics models at the nanoscale is still an open question31.

Fixing the exponent p for the whole surface, we generate a map of the stiffness factor as shown in Fig. 4e. Typically, dynamic AFM requires an order of magnitude difference in stiffness to show image contrast. The high force accuracy of our measurement allows for the resolution of a factor of three difference in stiffness as shown in Fig. 4f. The PMMA-rich domains are stiffer than the PS-rich matrix, in agreement with previous measurements32 and in agreement with the expected bulk modulus33.

Local stiffness is a property typically extracted from the conservative part of the surface force. However, dissipative interactions are also present, which was recognized early in the history of dynamic AFM15,20,34. These dissipative interactions are far more complex, as they depend not only on tip position z, but also on the velocity and the history of tip motion. To get a signature of the dissipation mechanism we use equation 10 to reconstruct the energy loss per oscillation cycle as a function of the oscillation amplitude A. To demonstrate this, we scanned a heterogeneous blend of PS and low-density polyethylene (LDPE). Figure 5a shows the surface topography of the blend where LDPE aggregates to form droplet-like structures. Figure 5b show typical conservative force and energy loss curves reconstructed with ADFS on each of the two domains. For both domains, the dissipated energy in Fig. 5c increases significantly in the repulsive region of the conservative tip–surface force. For LDPE, we see that both the dissipation and the size of the interaction region are much larger than for PS. Moreover, on LDPE the conservative force stays in the net attractive regime. We can interpret these observations as resulting from greater positive and negative surface deformation as the tip approaches and retracts above LPDE. This interpretation is supported by the fact that the LDPE domains are not in the stiff glass phase, as the glass transition temperature of LDPE is below room temperature33.

Liquid environments and high-frequency cantilevers

The presented remarkably fast and accurate force measurements were performed with standard cantilevers and under ambient conditions. However, one reason for the widespread use of AFM is the ability to image with a huge variety of cantilevers in different environments such as liquids. We therefore consider the applicability of ADFS in different operating regimes.

The ADFS data acquisition scheme is based on a slow modulation of the tip oscillation amplitude, which can be achieved by driving with two pure tones close to the first flexural cantilever resonance. The spacing between the drive frequencies determines the measurement bandwidth Δf and in turn the measurement time T=1/Δf. Higher measurement speed (scanning speed) therefore requires larger spacing between the drive frequencies. The tip–surface force generates new frequency components in the spectrum of the tip motion near resonance, with spacing Δf (ref. 23). These new components contain the information for the ADFS reconstruction and usually the measurement of approximately 20 frequency components is required for an accurate ADFS reconstruction, as we have verified with simulations. The measurement therefore requires a frequency band around resonance broad enough to collect these 20 frequency components with a SNR larger than 1. We call this frequency band the resonant detection band.

The accuracy and speed of the ADFS technique improves with increasing width of this resonant detection band. In this band, the tip dynamics z(t) are well represented by the single harmonic oscillator, which in Fourier space is described by the linear response function  given by

given by

with the imaginary unit i. The linear response function is fully characterized by the parameters k, ω0 and Q, which depend on the cantilever and the environment. For a given force, the response spectrum  is given by equation 5 and the detector noise level determines the width of the resonant detection band.

is given by equation 5 and the detector noise level determines the width of the resonant detection band.

For the sake of discussion, we take the detector noise level to be frequency-independent (white noise) with an amplitude of 150 fm/√Hz and a measurement bandwidth of 500 Hz. In Fig. 6a, we show the resonant detection band for a sinusoidal force of strength 10 pN applied to a cantilever having resonance frequency 300 kHz, with different spring constants and quality factors. The red curve shows that a significant reduction of the quality factor does not decrease the width of the resonant detection band. On the other hand, reducing the cantilever spring constant (for fixed ω0 and Q) does strongly increase the width of the resonant detection band. In Fig. 6b, the width of the resonant detection band is plotted as a function of spring constant and quality factor for fixed ω0. We note that for Q larger than a low threshold value, the width, the resonant detection band is independent of Q and increases inversely with the spring constant k. Thus, decreasing k appears advantageous. However, the spring constant k should not be too small, as for cantilevers with small spring constant the dependence of the motion on the non-linear tip–surface force in equation 1 becomes stronger and the motion can become chaotic35,36. Smaller k also results in the generation of higher harmonics19,37 and excitation of higher cantilever eigenmodes38,39, which distort the motion so that it is no longer nearly sinusoidal.

(a) Frequency-dependent cantilever response to a force of 0.01 nN. The noise level is determined for white detector noise of 150 fm/√Hz and a measurement bandwidth of Δf=500 Hz. For an AFM cantilever with a resonance frequency of ω0=2π·300 kHz, the width of the resonant detection band (shaded regions) is nearly independent of the quality factor but depends strongly on the spring constant. (b) Continuous dependence of the resonant detection bandwidth on the spring constant and quality factor for a cantilever with a fixed resonance frequency of ω0=2π·300 kHz. Above a threshold value of Q, the width of the resonant detection band is independent of the quality factor. (c) Frequency-dependent cantilever response to a force of 0.01 nN for typical cantilevers with resonance frequencies of ω0=2π·75 kHz (blue), 300 kHz (red) and 1,500 kHz (green). The width of the resonant detection band (shaded regions) increases for higher resonant frequency and lower spring constant. (d) Continuous dependence of the resonant detection bandwidth on the spring constant and resonant frequency for a cantilever with quality factor of Q=300.

Another cantilever parameter that can be changed is the resonance frequency ω0. Recently, low mass cantilevers with resonance frequency up to 2 MHz have become commercially available. As can be seen in Fig. 6c, the width of the resonant detection band increases linearly with the resonance frequency (at fixed quality factor Q). One should note that these low mass cantilevers are shorter than conventional cantilevers, which yields a bigger deflection angle for the same amplitude of tip motion, resulting in greater responsivity of the optical lever system. This increased responsivity lowers the detection noise floor, further increasing the resonant detection bandwidth. Thus, the multi-frequency data acquisition scheme used for ADFS benefits strongly from this trend toward higher frequency cantilevers.

For operation in liquids, often cantilevers with lower resonance frequencies and lower spring constants are used. A small spring constant compensates for the decrease of the resonant detection bandwidth due to the lower resonance frequency. However, both spring constant and the resonance frequency should not be too small to avoid distortion of the motion from higher harmonics19,37 and higher eigenmodes38,39. Maximum oscillation amplitudes below 10 nm and high setpoint values also help to reduce these higher frequency contributions, as has been demonstrated for torsional force sensors40. Finally, we do not want the resonant detection band to spread to too low frequencies where 1/f-noise becomes dominant. To achieve these goals, resonance frequencies of ω0≈2π·75 kHz and spring constants of k≈4 N/m should be sufficient.

Our discussion thus far has focused on maximizing the resonant detection bandwidth for a given detector noise. However, the SNR within this band will have a contribution from the thermal noise force connected with the damping of the cantilever motion in the surrounding medium. The thermal noise force is independent of frequency and its magnitude is given by the fluctuation dissipation theorem as

When going from air to liquid for fixed spring constant k, the thermal noise force will significantly increase due to the reduction in ω0 and Q. If the thermal noise dominates over the detector noise, it can be shown that the SNR is independent of the spring constant k (ref. 41).

Discussion

We demonstrated accurate and high-resolution measurements of the conservative force and the dissipated energy while scanning. A direct analysis of the measured tip motion allows us to gain insight detailed information about the nature of the tip–surface interaction and dissipation mechanisms without extensive modelling based on idealized assumptions about the geometry of the tip and the surface. Such insight is often necessary to understand the contrast mechanism in AFM images.

ADFS requires only a narrow detection band whose width is basically independent of the cantilever quality factor. Therefore, ADFS can also be used for investigating biological samples in highly damped liquid environments with present-day noise detection limits. However, the tip motion has to be approximately sinusoidal on the level of single oscillation cycles.

Furthermore, ADFS is compatible with the current trend in AFM towards smaller, higher frequency probes42,43,44, as the width of the detection band increases linearly with the cantilever resonance frequency. With future generations of high-frequency force sensors, we envision that ADFS will enable high-resolution force–volume measurement at video rate.

The general idea of exploring amplitude dependence can also be extended to other modes of AFM like frequency-modulated AFM, torsional shear force microscopy or frictional force microscopy. Beyond AFM, the ADFS concept may inspire the development of new sensing schemes, as the basic concepts presented here are applicable to many types of measurements, which exploit the enhanced sensitivity of a high-quality-factor resonator.

Methods

Force reconstruction

For a single drive frequency, the tip motion is approximately sinusoidal as given by equation 3 and the corresponding tip velocity becomes

As the tip oscillates, it experiences the surface force, which is described as a function of tip position z and tip velocity ż. The force is usually decomposed into a conservative part and into a dissipative or non-conservative part as in equation 2. The conservative force is considered to be a function of only the tip position z, whereas the dissipative part depends also on the tip velocity ż, such that the dissipative force is anti-symmetric with respect to the velocity

If the tip motion contains only one frequency, only two real-valued Fourier components of the time-dependent force between tip and surface are measurable. With an appropriate shift of coordinates we set h=0 and with equations 2, 3, 14 and 15, these components given in equations 6 and 7 can be written as

We note that FI and FQ are functions of the oscillation amplitude and that FI depends only on the conservative part of the tip–sample interaction, whereas FQ is only affected by the dissipative interaction.

With the substitution z′=A cos(ω0t), we rewrite equation 16 as

The tip–surface interaction is localized to a small region close to the surface, which is small compared with the oscillation amplitude. With this assumption and the substitution u=z′2, one obtains equation 8 Now, we define  ,

,  and

and  , and rewrite equation 8 as

, and rewrite equation 8 as

Equation 19 reveals that  is the Abel transform of

is the Abel transform of  . Similar integrals have been studied before5,6,7, but they were never considered as a function of amplitude. The Abel transform has a unique inverse21, which enables the solution of equation 19 for the force

. Similar integrals have been studied before5,6,7, but they were never considered as a function of amplitude. The Abel transform has a unique inverse21, which enables the solution of equation 19 for the force

which can readily be rewritten as equation 9. For experimental data, equation 9 has to be evaluated numerically. To improve the numerical stability, we perform the substitution  , which removes the square root singularity,

, which removes the square root singularity,

With equation 21, we can reconstruct the conservative tip–surface interaction without any assumption regarding its functional representation.

The non-conservative interaction can be characterized by the energy dissipated per oscillation cycle,

With equations 14 and 22, we can rewrite the integral equation 16 in terms of the dissipated energy Edis,

which allows for the study of the energy dissipation from the amplitude dependence of FQ(A) as in equation 10.

Numerical methods

The numerical simulations have been performed using the CVODE adaptive step-size integrator45. Special care was taken to treat the non-smooth transition between attractive and repulsive forces at z=0 in the force defined by equation 4.

Experimental methods

PS (Mw=280 kDa), PMMA (Mw=120 kDa) and toluene were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and used as purchased. The polymers were dissolved in toluene at a concentration of 0.52 wt% and spin-cast on a silicon substrate. The sample was scanned with a Multimode AFM and a Nanoscope 4 controller (Bruker). The PS/LDPE sample (Bruker) was scanned with a Dimension 3100 AFM and a Nanoscope 3a controller (Bruker). Both AFM systems were used together with a signal access module and a multi-frequency lock-in analyser (Intermodulation Products AB, IMP 2-32) for drive synthesis and signal analysis. All scans have been performed with Tap300Al-G probes (Budget Sensors), which were calibrated with a non-invasive thermal method46.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Platz, D. et al. Interaction imaging with amplitude-dependence force spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 4:1360 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2365 (2013).

References

Mamin H. J., Rugar D. Sub-attonewton force detection at millikelvin temperatures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 3358–3360 (2001).

Jensen K., Kim K., Zettl A. An atomic-resolution nanomechanical mass sensor. Nat. Nanotech. 3, 533–537 (2008).

LaHaye M. D., Buu O., Camarota B., Schwab K. C. Approaching the quantum limit of a nanomechanical resonator. Science 304, 74–77 (2004).

Giessibl F. J. Atomic resolution of the silicon (111)-(7 × 7) surface by atomic force microscopy. Science 267, 68–71 (1995).

Dürig U. Extracting interaction forces and complementary observables in dynamic probe microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 76, 1203–1205 (2000).

Sader J. E. et al. Quantitative force measurements using frequency modulation atomic force microscopy—theoretical foundations. Nanotechnology 16, S94–S101 (2005).

Hölscher H. Quantitative measurement of tip-sample interactions in amplitude modulation atomic force microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 123109 (2006).

Lee M., Jhe W. General theory of amplitude-modulation atomic force microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 036104 (2006).

Hu S., Raman A. Inverting amplitude and phase to reconstruct tip-sample interaction forces in tapping mode atomic force microscopy. Nanotechnology 19, 375704 (2008).

Katan A. J., van Es M. H., Oosterkamp T. H. Quantitative force versus distance measurements in amplitude modulation AFM: a novel force inversion technique. Nanotechnology 20, 165703 (2009).

Hölscher H., Langkat S. M., Schwarz A., Wiesendanger R. Measurement of three-dimensional force fields with atomic resolution using dynamic force spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 4428–4430 (2002).

Baykara M. Z., Schwendemann T. C., Altman E. I., Schwarz U. D. Three-dimensional atomic force microscopy—taking surface imaging to the next level. Adv. Mater. 22, 2838–2853 (2010).

Albers B. J. et al. Three-dimensional imaging of short-range chemical forces with picometre resolution. Nat. Nanotech. 4, 307–310 (2009).

Melcher J., Hu S., Raman A. Equivalent point-mass models of continuous atomic force microscope probes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 053101 (2007).

Cleveland J. P., Anczykowski B., Schmid A. E., Elings V. B. Energy dissipation in tapping-mode atomic force microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 72, 2613–2615 (1998).

Stark M., Stark R. W., Heckl W. M., Guckenberger R. Inverting dynamic force microscopy: from signals to time-resolved interaction forces. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 8473–8478 (2002).

Dürig U. Interaction sensing in dynamic force microscopy. N. J. Phys. 2, 5 (2000).

Sahin O., Magonov S., Su C., Quate C. F., Solgaard O. An atomic force microscope tip designed to measure time-varying nanomechanical forces. Nat. Nanotech. 2, 507–514 (2007).

Legleiter J., Park M., Cusick B., Kowalewski T. Scanning probe acceleration microscopy (SPAM) in fluids: mapping mechanical properties of surfaces at the nanoscale. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 4813–4818 (2006).

San Paulo A., Garcia R. Tip-surface forces, amplitude, and energy dissipation in amplitude-modulation (tapping mode) force microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 64, 193411 (2001).

Arfken G. B., Weber H. J. Mathematical Methods for Physicists Elsevir Academic Press (2005).

Garcia R. et al. Identification of nanoscale dissipation processes by dynamic atomic force microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 016103 (2006).

Tholén E. A. et al. Note: The intermodulation lockin analyzer. Rev. Sci. Instr. 82, 026109 (2011).

Cuberes M. T., Briggs G. A. D., Kolosov O. Nonlinear detection of ultrasonic vibration of AFM cantilevers in and out of contact with the sample. Nanotechnology 12, 53–59 (2001).

Jesse S., Kalinin S. V., Proksch R., Baddorf A. P., Rodriguez B. J. The band excitation method in scanning probe microscopy for rapid mapping of energy dissipation on the nanoscale. Nanotechnology 18, 435503 (2007).

Seo Y., Jhe W. Atomic force microscopy and spectroscopy. Rep. Progr. Phys. 71, 016101 (2008).

Walheim S., Böltau M., Mlynek J., Krausch G., Steiner U. Structure formation via polymer demixing in spin-cast films. Macromolecules 30, 4995–5003 (1997).

Sneddon I. N. The relation between load and penetration in the axisymmetric boussinesq problem for a punch of arbitrary profile. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 3, 47–57 (1965).

Johnson K. L. Contact Mechanics 1st edn Cambridge University Press (1985).

Derjaguin B. V., Muller V. M., Toporov Y. P. Effect of contact deformations on the adhesion of particles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 53, 314–326 (1975).

Luan B., Robbins M. O. The breakdown of continuum models for mechanical contacts. Nature 435, 929–932 (2005).

Sahin O., Erina N. High-resolution and large dynamic range nanomechanical mapping in tapping-mode atomic force microscopy. Nanotechnology 19, 445717 (2008).

Brandrup J., Immergut H., Grulke E. A., Abe A., Bloch D. R. Polymer Handbook 4th edn Wiley & Sons (2005).

Garcia R., Magerle R., Pérez R. Nanoscale compositional mapping with gentle forces. Nat. Mater. 6, 405–411 (2007).

Hu S., Raman A. Chaos in atomic force microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 036107 (2006).

Jamitzky F., Stark M., Bunk W., Heckl W. M., Stark R. W. Chaos in dynamic atomic force microscopy. Nanotechnology 17, S213–S220 (2006).

Stark R. W. Bistability, higher harmonics, and chaos in AFM. Mater. Today 13, 24–32 (2010).

Basak S., Raman A. Dynamics of tapping mode atomic force microscopy in liquids: theory and experiments. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 064107 (2007).

Melcher J., Xu X., Raman A. Multiple impact regimes in liquid environment dynamic atomic force microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 093111 (2008).

Dong M., Husale S., Sahin O. Determination of protein structural flexibility by microsecond force spectroscopy. Nat. Nanotech. 4, 514–517 (2009).

Platz D., Forchheimer D., Tholén E. A., Haviland D. B. The role of nonlinear dynamics in quantitative atomic force microscopy. Nanotechnology 23, 265705 (2012).

Li M., Tang H. X., Roukes M. L. Ultra-sensitive NEMS-based cantilevers for sensing, scanned probe and very high-frequency applications. Nat. Nanotech. 2, 114–120 (2007).

Arlett J. L., Myers E. B., Roukes M. L. Comparative advantages of mechanical biosensors. Nat. Nanotech. 6, 203–215 (2011).

Mininni L., Slade A., Kindt J., Hu S. High-speed atomic force microscopy enables new applications. Microscopy Today 19, 12–15 (2011).

Hindmarsh A. C. et al. SUNDIALS: Suite of nonlinear and differential/algebraic equation solvers. ACM Trans. Math. Software 31, 363–396 (2005).

Higgins M. J. et al. Noninvasive determination of optical lever sensitivity in atomic force microscopy. Rev. Sci. Instr. 77, 013701 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support from the Swedish Research Council (VR) and the Swedish Government Agency for Innovation Systems (VINNOVA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.P. developed the measurement concept and the theory. D.P. fabricated the PS/PMMA sample. All authors contributed to the experimental setup. D.P. and D.F. performed the measurements. D.P. analysed the data. D.P. and D.B.H wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed and contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Two patent applications ('Intermodulation Scanning Force Spectroscopy', PCT/EP2008/066247 and 'Intermodulation Lock-in', USPTO 13098597) on the multi-frequency measurement techniques have been filed by the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Platz, D., Forchheimer, D., Tholén, E. et al. Interaction imaging with amplitude-dependence force spectroscopy. Nat Commun 4, 1360 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2365

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2365

This article is cited by

-

Fast and high-resolution mapping of elastic properties of biomolecules and polymers with bimodal AFM

Nature Protocols (2018)

-

Imaging high-speed friction at the nanometer scale

Nature Communications (2016)

-

Imaging and three-dimensional reconstruction of chemical groups inside a protein complex using atomic force microscopy

Nature Nanotechnology (2015)

-

Improving image contrast and material discrimination with nonlinear response in bimodal atomic force microscopy

Nature Communications (2015)

-

Fast nanomechanical spectroscopy of soft matter

Nature Communications (2014)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.