Abstract

The U.S. mid-Atlantic sea-level record is sensitive to the history of the Laurentide Ice Sheet as the coastline lies along the ice sheet’s peripheral bulge. However, paleo sea-level markers on the present-day shoreline of Virginia and North Carolina dated to Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 3, from 50 to 35 ka, are surprisingly high for this glacial interval, and remain unexplained by previous models of ice age adjustment or other local (for example, tectonic) effects. Here, we reconcile this sea-level record using a revised model of glacial isostatic adjustment characterized by a peak global mean sea level during MIS 3 of approximately −40 m, and far less ice volume within the eastern sector of the Laurentide Ice Sheet than traditional reconstructions for this interval. We conclude that the Laurentide Ice Sheet experienced a phase of very rapid growth in the 15 kyr leading into the Last Glacial Maximum, thus highlighting the potential of mid-field sea-level records to constrain areal extent of ice cover during glacial intervals with sparse geological observables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reconstructing the pace of ice growth towards the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, 26 ka) is critical to our understanding of ice age climate and ice sheet stability. Nevertheless, global ice volume, or equivalent global mean sea level (GMSL), and the corresponding geographical distribution of ice remain uncertain through Marine Isotope Stage 3 (MIS 3; 60–26 ka) leading into the LGM1,2. Oxygen isotope records from marine sediment cores provide a proxy for global ice volume after correcting for temperature-dependent fractionation3, however uncertainties in this correction and other complications in mapping isotope values to ice volumes have yielded estimates of peak MIS 3 GMSL that range from −30 to −60 m relative to present day1. Geological records of sea level during MIS 3 are sparse because ancient markers in the far field of former ice sheets are presently submerged, while those in the near field have been erased by the subsequent advance and retreat of the major continental ice sheets4,5. Moreover, glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA) and tectonic uplift contaminate the present-day elevation of available sea-level records6,7. Studies that applied GIA modelling to fit oxygen isotope records and geological sea-level markers have published discordant inferences of peak MIS 3 GMSL, varying from −85 m (ref. 8) to −55 m (ref. 9), and most recently −37.5±7 m (ref. 10).

The geological markers of Pleistocene sea-level oscillations extending from Virginia to North Carolina in the Albemarle Embayment (Fig. 1), on the Laurentide Ice Sheet’s (LIS) peripheral bulge, require a re-evaluation of ice volume and extent during MIS 3. This record indicates that MIS 3 relative sea level (RSL) reached present-day levels from ∼50 to 35 ka in this region11,12,13,14,15,16 (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 1), but GIA calculations predict that these markers should presently be found as much as ∼70 m below sea level8. Tectonic uplift of the markers is insufficient to explain their present-day elevation17,18 and sediment compaction has led to only minor subsidence in this region19.

Field localities are shown by yellow dots on the inset map. Upwards pointing triangles represent marine indicators (lower bound), downwards-oriented triangles represent terrestrial indicators (upper bound), and circles designate tidal facies. Error bars span 2-σ age uncertainties on individual sea-level data. Marine Isotope Stages 5e, 5c, 5a and 3 are labelled at 120, 100, 80 and 60–26 ka, respectively. The shaded region covers the time interval examined within the present analysis and the orange rectangles mark the bounds on MIS 5a and MIS 3 sea level based on the plotted data (MIS 5a: 2.5–7.5 m; MIS 3: −1 to 1 m). The white star on the inset map marks the location of RSL predictions presented herein.

Here, we present a new set of GIA calculations that explore the sensitivity of the predictions to peak GMSL and LIS geometry during MIS 3. We conclude that a revised GIA model can reconcile the MIS 3 sea-level record at the Albemarle Embayment under two conditions: (1) peak GMSL reached near −40 m and (2) the eastern sector of LIS was significantly reduced during MIS 3 compared with previous reconstructions of ice extent.

Results

The U.S. Mid-Atlantic sea-level record

The Albemarle Embayment geological record includes interfluvial, estuarine, intertidal and shallow marine lithofacies arranged in depositional sequences that record repeated sea-level highstands dated primarily by optically stimulated luminescence to MIS 5e, 5c, 5a and 3 (ref. 11) (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 1; Supplementary Note 1). We adopt the minimum elevation of terrestrial facies and the maximum elevation of marine facies as upper and lower bounds, respectively, of MIS 5a (∼80 ka) and mid-MIS 3 (50–35 ka) sea level. For the MIS 5a data (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 1), we bound a cluster of sea-level data from 2.5 to 7 m in agreement with previous assessments of sea-level records in the region20. We assume that rare terrestrial markers found at elevations below this range do not represent a constraint on the MIS 5a highstand, but rather a lower sea level reached during late MIS 5a or MIS 4. Furthermore, calculations described below (and detailed in Supplementary Note 3) demonstrate that RSL predictions for MIS 3 are relatively insensitive to the height of sea level during MIS 5a.

For the MIS 3 interval spanning 50–35 ka, three marine indicators constrain RSL to be above −0.9, −3 and −2 m (ref. 11). We thus adopt the elevation of the highest of these marine indicators, −0.9 m, as the lower bound. Regarding the upper bound, three terrestrial indicators, with ages between 50 and 35 ka, show a consistent constraint on the sea-level highstand of 1 m. Two terrestrial indicators dated to earlier in this time window13 are found at lower elevations, however these may represent deposition during a time of rising sea level rather than during the peak sea-level highstand. We adopt the terrestrial indicators at 1 m as the upper bound on sea level, yielding a range of −1 to 1 m. We apply an elevation error of ±3 m that reflects reconstructed paleo-tidal range for the region that may have been up to three times greater than the present amplitude of ∼1 m (ref. 21). The geological sea-level constraints we adopt below (for example, Fig. 2) incorporate these broader uncertainties.

(a) Global mean sea-level curve for Version 1.2 of ICE-5G (dotted black line) and the ICEPC (blue line) ice histories. The GMSL curve for the ICEPC2 history is identical to the curve for ICEPC. (b) Relative sea-level predictions for the reference site in the Albemarle Embayment based on the ICE-5G (dotted black), ICEPC (solid blue) and ICEPC2 (dashed blue; ice-free eastern sector of the Laurentide Ice Sheet from 80 to 44 ka) ice histories. Orange rectangles span the observational constraints on peak MIS 5a and 3 sea level including the ±3 m paleotidal uncertainty (see Fig. 1). For MIS 5a, this range is −0.5 to 10.5 m, and at 44 ka during MIS 3 the range is −4 to 4 m. The grey-shaded region spans the MIS 3 time interval examined within the present analysis.

Models of glacio-isostatic adjustment

Ice sheet growth and melt produces a complex spatio-temporal pattern of sea-level change22. To predict the present elevation of sea-level markers, we perform calculations based on the sea-level theory and pseudo-spectral algorithm described by Kendall et al.23 with a spherical harmonic truncation at degree and order 256. The calculations include the impact of rotation changes on sea level24, evolving shorelines and the migration of grounded, marine-based ice23,25,26,27. We report RSL predictions at a representative site within the Albemarle Embayment (white star on inset of Fig. 1) for a representative time (44 ka) within the middle of MIS 3 (50–35 ka). This representative site lies within the latitudinal range of the reported geological sea-level markers used to define the bound on local peak MIS 3 sea level (Fig. 1). We have found that RSL highstand predictions for this reference site differ from field locations by less than 0.5 m. We deem simulations acceptable if they satisfy the aforementioned bounds for both MIS 5a and MIS 3 (Fig. 2b, orange rectangles).

Our numerical predictions require models for Earth’s viscoelastic structure and the history of global ice cover. We begin by adopting an Earth model with upper and lower mantle viscosities of 0.5 × 1021 Pa s and 1.5 × 1022 Pa s, respectively; this radial profile is consistent with inferences based on globally distributed ice age data sets28 and geological data along the U.S. mid-Atlantic29,30. Our initial GIA calculation adopts Version 1.2 of the ICE-5G ice history, characterized by a GMSL fall from −87 to −100 m throughout MIS 3 (ref. 8) (Fig. 2a; dotted black line); in this calculation, we make the standard assumption that, for any pre-LGM time step, the geometry of global ice cover was identical to the post-LGM ice distribution with the same GMSL value31. We explore alternatives to the GMSL history, ice geometry and viscosity profile in the discussion below. Using the combination of the ICE-5G model and Earth structure described above, we predict mid-MIS 3 sea level (at 44 ka) at the Albemarle Embayment reference site to be –67 m (Fig. 2b; dotted black line), grossly misfitting (by ∼70 m) the observational constraints (Fig. 1). The misfit is ∼25 m for the MIS 5a record (Fig. 2b). The level of misfit to the MIS 3 record highlights the enigmatic nature of the sea-level record in Fig. 1 and motivates the present study.

Many previous inferences of GMSL during the last glacial phase, particularly MIS 3, reconstruct higher peak sea level (smaller global ice volume) than adopted in the ICE-5G history9,32,33. To proceed in our analysis, we revise the ICE-5G ice history on the basis of results from two recent GIA analyses. First, following the Pico et al.10 analysis of sediment core records from the Bohai Sea, peak GMSL during MIS 3 is placed at −37.5 m at 44 ka. Second, we adopt GMSL values of −15 and −10 m for MIS 5a and 5c, respectively; these values are within bounds (5a: −18 to 0 m, 5c: −20 to 1 m) derived by Creveling et al.30 on the basis of globally distributed sea-level markers from both periods. The GMSL curve for the revised ice model, ICEPC, is shown in Fig. 2a (blue line). The RSL prediction based on this model (Fig. 2b, solid blue) maintains the assumption that the pre-LGM global ice geometry is equivalent to the deglacial phase whenever GMSL values are equal. This prediction is consistent with observational constraints for the MIS 5a highstand, but misfits MIS 3 data. Notably, this Earth–ice model pairing predicts a peak RSL of −12 m at 44 ka, well below the observational bounds of −4 to 4 m.

We performed a suite of simulations to explore the sensitivity of our predictions to the adopted ice history. Specifically, we generated 100 synthetic ice histories in which we varied GMSL randomly across the glacial phase but confined GMSL to −37.5±7 m at 44 ka (ref. 10), and to −15 m and −10 m, for MIS 5a and MIS 5c, respectively (Fig. 3a, blue lines; see Methods for detailed ice history construction). Using these ice histories, we predicted RSL at the reference site within the Albemarle Embayment using the standard treatment for the pre-LGM ice distribution; that is, this distribution matches the post-LGM geometry when the GMSL values are the same (similar to ICEPC). In this case, the predicted RSL ranges from −26.5 to −7.5 m at 44 ka (blue lines, Fig. 3b), and thus all 100 simulations predict a peak RSL that falls outside the observational constraints.

(a) Global mean sea level curves for 100 randomly generated ice histories that pass through −37.5±7 m at 44 ka (blue lines), −15 m at MIS 5a and −10 m at MIS 5c. (b) Relative sea level predictions for the Albemarle Embayment reference site based on the ice histories shown in frame (a). The results of calculations that assume identical pre-LGM and post-LGM ice geometries when global mean sea level values are the same are plotted as blue lines; the calculations that assume an ice-free eastern Laurentide from 80 to 44 ka are shown by black lines. Orange rectangles span the adopted observational constraints on peak MIS 5a and MIS 3 sea level including the ±3 m paleotidal uncertainty. The grey-shaded region spans the MIS 3 time interval examined within the present analysis.

Revising the geometry of the Laurentide Ice Sheet during MIS 3

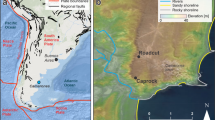

We next explored the impact of changing the geometry of the LIS on the local RSL predictions at the Albemarle Embayment. While few field data constrain the evolution of the LIS before the LGM2,4,5, a recent field-based study by Dalton et al.34 suggests that large portions of eastern Laurentia were ice-free during MIS 3 (Fig. 4). This conclusion implies limited or no ice growth from MIS 5a to MIS 3 within large areas of the sector of the LIS closest to the Albemarle Embayment. To investigate the effect of this revised ice geometry on RSL predictions, we constructed an ice model, ICEPC2, with a GMSL history identical to that shown by the blue line in Fig. 2a, but that was distinguished from the ICEPC history in the following ways: (1) the eastern sector of the LIS is ice-free from 80 to 44 ka, consistent with the conclusions of Dalton et al.34; and (2) the ice removed in this exercise, equivalent to 6.8 m of GMSL, is distributed uniformly over the western sector of the LIS, and the Cordilleran and Fennoscandian Ice Sheets. The latter resulted in an increase in ice thickness of ∼170 m in each region (Fig. 4; See Methods for details on ice model construction). The post-LGM ice geometry remains identical to the ICE-5G and ICEPC models, and thus we no longer assume that global ice geometry prior and subsequent to the LGM were identical whenever the GMSL values match. The simulation, based on this revised ICEPC2 ice model and the viscoelastic Earth model discussed above, predicts a RSL of −3 m at 44 ka, consistent with the sea-level record at the Albemarle Embayment (Fig. 2b).

At LGM in the ICE-5G model (dashed black line) and showing the eastern extent of the ice model ICEPC2 from MIS 5a to MIS 3 (dotted black line). Repulse Bay, Hudson Bay Lowlands, Southern Ontario, and Atlantic Canada are all sites that have been reported as deglaciated at MIS 3 in Dalton et al.34

Discussion

What physics underlies this improved fit to the MIS 3 sea-level record in the mid-Atlantic coastal region? Crustal deformation and the direct gravitational effect of the surface load dominate sea-level predictions in this location and yield a RSL history that departs significantly from GMSL. To assess the relative contribution of each process, we decomposed the RSL prediction based on ice models ICEPC and ICEPC2 into these two components (Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Note 2). Ice model ICEPC2 is defined by a reduced eastern sector of the LIS, and therefore a smaller surface load compared with the ICEPC model. This smaller ice load results in a reduced direct gravitational effect (expressed as a sea-level fall) and a reduced crustal deformation (a smaller upward deflection of the Earth’s surface, expressed as sea-level rise), compared to the ICEPC prediction. The latter effect dominates, resulting in a net sea-level rise compared to the ICEPC ice distribution and the fit evident in Fig. 2b (dashed blue line). We explore the sensitivity of the RSL decomposition to variations in Earth structure in Supplementary Note 4, where we adopt the ICEPC2 ice history and consider a range of lithospheric thicknesses, and upper and lower mantle viscosities (see Supplementary Fig. 2).

We performed several additional sensitivity tests related to the ICEPC2 simulation. For example, we once again randomly generated 100 simulations, and constructed ice histories with the GMSL curves shown in Fig. 3a, but now assumed (as in ICEPC2) that the eastern sector of the LIS was ice-free from 80 to 44 ka. In these simulations, the predicted peak RSL at the reference site in the Albemarle Embayment ranged from −11 to −1 m at 44 ka (black lines, Fig. 3b). Nearly half (46 of 100) of these simulations yielded predictions consistent with observational constraints on the MIS 3 highstand. We also constructed ice histories in which we varied peak GMSL during MIS 5a and MIS 5c in the range of −16 to 0 m and −20 to 0 m, respectively, within bounds derived by Creveling et al.30, to test the sensitivity of the RSL predictions to this level of uncertainty. This suite of simulations perturbed the peak RSL prediction during MIS 3 by less than 0.7 m, and thus our conclusions in regard to ice cover during MIS 3 are insensitive to the GMSL values adopted for MIS 5a and 5c.

We also performed tests in which the geometry of ice removed from the eastern sector of the LIS was varied by shifting the upper latitudinal limit of the ice-free region, and by considering scenarios in which various regions within the eastern sector of the LIS remained glaciated (see Supplementary Fig. 3). We conclude that increasing the ice in the eastern sector by 20% of the ice volume removed to construct the ice history ICEPC2 (or 1.5 m GMSL) from 80 to 44 ka, and shifting the distribution of this ice within the sector, can lower the RSL predictions by up to 3 m (Supplementary Table 2). Finally, to assess the sensitivity of the predictions to the adopted Earth model, we ran simulations in which the lower mantle viscosity was both increased and decreased by 5 × 1021 Pa s. The predicted RSL at 44 ka was perturbed by a maximum of 3 m at the Albemarle Embayment (Supplementary Fig. 4). We also ran simulations with an additional six Earth models to assess the sensitivity of RSL predictions to lithospheric thickness and upper mantle viscosity (details in Supplementary Note 4; Supplementary Fig. 5).

Finally, additional constraints exist on RSL during MIS 3 at other sites along the U.S. East Coast. For example, a marine indicator at −30 m on the Hudson Shelf of age ∼45 ka provides a lower bound on sea level at this site35, while terrestrial facies in the Chesapeake Bay indicate that local sea level was below approximately −7.6 m sometime during the interval 50–35 ka (ref. 36). RSL predictions based on ice model ICEPC2 agree well with both these constraints (Fig. 5).

The Albemarle Embayment site is shown by the white star. Elevation of sea level data are plotted as triangles at the Chesapeake Bay (−7.6 m, −1.7 m and −3.4 m) and the Hudson shelf (−30 m), where the colour represents the elevation shown by the colour bar. Upper bounds on sea level are represented by downwards pointing triangles, while lower bounds are plotted as upwards pointing triangles.

Sea-level records from the mid-Atlantic coastal plain show that MIS 3 sea level reached present-day levels. These observations have been considered enigmatic given that previously published GIA models predict RSL in this region to be more than 60 m below present level at MIS 3 (ref. 18). However, we have shown that GIA models can be reconciled with the observational record from the Albemarle Embayment under two conditions: (1) global mean sea level during MIS 3 reached approximately −40 m, consistent with a recent analysis of sediment core records from the Bohai Sea10 and within the bounds of several earlier studies37,38,39,40,41,42,43; and (2) the eastern sector of the LIS remained largely ice-free over an extended period from MIS 5a through mid-MIS 3, consistent with recent field-based evidence34. Rigorous tests of our conclusions regarding ice extent will require improved chronological control on geological indicators of LIS extent, as presented in, for example, Clark et al.5, Curry et al.44, Colgan et al.45 and Dalton et al.34. Our inference, if robust, implies that the LIS rapidly advanced during the ∼15 kyr from mid-MIS 3 to the Last Glacial Maximum. Moreover, our study highlights the potential of mid-field sea-level records to constrain ice load locations over glacial intervals where geologic evidence of ice cover is poorly preserved.

Methods

Ice history construction

We created 100 ice models that are distinguished from Version 1.2 of ICE-5G (Peltier & Fairbanks, 2006) by their GMSL history before the Last Glacial Maximum. These ice histories randomly sample GMSL values under the following constraints: at LIG, 122 ka, GMSL=0; at 110 ka, MIS 5d, GMSL=−40 m; at MIS 5c, GMSL=−10 m; at MIS 5a, GMSL=−15 m; during MIS 3 before 44 ka, GMSL varies in the range −40 to −80 m; at 44 ka, the GMSL value is pinned within the range −37.5±7 m (Fig. 3a). We also impose the constraint that sea level must fall between 44 ka and LGM. We produce two sets of 100 ice models from these GMSL curves. The first set is constructed by assuming that ice geometry in the pre-LGM period is identical to the time in the post-LGM period with the same GMSL value. The second set assumes that a large portion of the eastern sector of the LIS is ice-free from 80 to 44 ka (see Fig. 4). In the latter case, the ice volume removed from the eastern sector of the LIS (equivalent GMSL of 6.8 m) is distributed over the LGM extent of the western sector of the LIS, the Cordilleran Ice Sheet and over Fennoscandia, resulting in an increase in ice thickness of 170 m in these regions.

We note that while RSL predictions at the Albemarle Embayment are sensitive to ice geometry of the eastern LIS, these predictions will be relatively insensitive to the geographic distribution of ice cover in regions in the far field of the mid-Atlantic U.S. East Coast. As an example, we performed a simple test in which the ice removed from the eastern sector of LIS to construct the ICEPC2 model was distributed uniformly over Fennoscandia and Antarctica (rather than over the western sector of the LIS) and found that the predicted sea-level highstand at our test site at 44 ka was only perturbed by 0.6 m.

Data availability

The data sets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Pico, T. et al. Sea-level records from the U.S. mid-Atlantic constrain Laurentide Ice Sheet extent during Marine Isotope Stage 3. Nat. Commun. 8, 15612 doi: 10.1038/ncomms15612 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Siddall, M., Rohling, E. J., Thompson, W. G. & Waelbroeck, C. Marine Isotope Stage 3 sea level fluctuations: data synthesis and new outlook. Hemisphere 46, 1–29 (2008).

Kleman, J. et al. North American Ice Sheet build-up during the last glacial cycle, 115–21 kyr. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 2036–2051 (2010).

Waelbroeck, C. et al. Sea-level and deep water temperature changes derived from benthic foraminifera isotopic records. Quat. Sci. Rev. 21, 295–305 (2002).

Dyke, A. S. et al. The Laurentide and Innuitian Ice Sheet during the Last Glacial Maximum. Quat. Sci. Reviews 21, 9–31 (2002).

Clark, P. U. et al. Initiation and development of the Laurentide and Cordillean Ice Sheets following the Last Interglaciation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 12, 79–114 (1993).

Chappell, J., Ota, Y. & Berryman, K. Late quaternary coseismic uplift history of Huon Peninsula, Papua New Guinea. Quat. Sci. Rev. 15, 7–22 (1996).

Mitrovica, J. X. & Milne, G. A. On the origin of late Holocene sea-level highstands within equatorial ocean basins. Quat. Sci. Rev. 21, 2179–2190 (2002).

Peltier, W. R. & Fairbanks, R. G. Global glacial ice volume and Last Glacial Maximum duration from an extended Barbados sea level record. Quat. Sci. Rev. 25, 3322–3337 (2006).

Lambeck, K. & Chappell, J. Sea level change through the last glacial cycle. Science 292, 679–686 (2001).

Pico, T., Mitrovica, J. X., Ferrier, K. L. & Braun, J. Global ice volume during MIS 3 inferred from a sea-level analysis of sedimentary core records in the Yellow River Delta. Quat. Sci. Rev. 152, 72–79 (2016).

Parham, P. R. et al. Quaternary coastal lithofacies, sequence development and stratigraphy in a passive margin setting, North Carolina and Virginia, USA. Sedimentology 60, 503–547 (2013).

Parham, P. R., Riggs, S. R., Culver, S. J., Mallinson, D. J. & Wehmiller, J. F. Quaternary depositional patterns and sea-level fluctuations, northeastern North Carolina. Quat. Res. 67, 83–99 (2007).

Mallinson, D., Burdette, K., Mahan, S. & Brook, G. Optically stimulated luminescence age controls on late Pleistocene and Holocene coastal lithosomes, North Carolina, USA. Quat. Res. 69, 97–109 (2008).

Culver, S. J. et al. Micropaleontologic record of Quaternary paleoenvironments in the Central Albemarle Embayment, North Carolina, U.S.A. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 305, 227–249 (2011).

Cronin, T. M., Szabo, B. J., Ager, T. A., Hazel, J. E. & Owens, J. P. Quaternary climates and sea levels of the U.S. Atlantic coastal plain. Science 211, 233–240 (1981).

Mixon, R., Szabo, B. J. & Owens, J. P. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1067-E (Surface and Shallow Subsurface Geologic Studies in the Emerged Coastal Plain of the Middle Atlantic States, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, 1982).

Van De Plassche, O. et al. Estimating tectonic uplift of the Cape Fear Arch (south-eastern United States) using reconstructions of Holocene relative sea level. J. Quat. Sci. 29, 749–759 (2014).

Doar, W. R. & Kendall, C. G. S. C. An analysis and comparison of observed Pleistocene South Carolina (USA) shoreline elevations with predicted elevations derived from Marine Oxygen Isotope Stages. Quat. Res. 82, 164–174 (2014).

Brain, M. J. et al. Quantifying the contribution of sediment compaction to late Holocene salt-marsh sea-level reconstructions, North Carolina, USA. Quat. Res. 83, 41–51 (2015).

Wehmiller, J. F., Edwards, R. L. & Martin-McNaughton, J. Uranium-series coral ages from the US Atlantic Coastal Plain-the ‘80 ka problem’ revisited. Quaternary International 120, 3–14 (2004).

Hill, D. F., Griffiths, S. D., Peltier, W. R., Horton, B. P. & Törnqvist, T. E. High-resolution numerical modeling of tides in the western Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico, and Caribbean Sea during the Holocene. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 116, 1–16 (2011).

Farrell, W. E. & Clark, J. A. On Postglacial Sea Level. Geophys. J. R. Astron. Soc. 46, 647–667 (1976).

Kendall, R. A., Mitrovica, J. X. & Milne, G. A. On post-glacial sea level - II. Numerical formulation and comparative results on spherically symmetric models. Geophys. J. Int. 161, 679–706 (2005).

Milne, G. A. & Mitrovica, J. X. Postglacial sea-level change on a rotating Earth: first results from a gravitationally self-consistent sea-level equation. Geophys. J. Int. 126, F13–F20 (1996).

Johnston, P. The effect of spatially non-uniform water loads on prediction of sea-level change. Geophys. J. Int. 114, 615–634 (1993).

Milne, G. A., Mitrovica, J. X. & Davis, J. L. Near-field hydro-isostasy: the implementation of a revised sea-level equation. Geophys. J. Int. 139, 464–482 (1999).

Lambeck, K., Purcell, A., Johnston, P., Nakada, M. & Yokoyama, Y. Water-load definition in the glacio-hydro-isostatic sea-level equation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 22, 309–318 (2003).

Mitrovica, J. X. & Forte, A. M. A new inference of mantle viscosity based upon joint inversion of convection and glacial isostatic adjustment data. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 225, 177–189 (2004).

Potter, E. K. & Lambeck, K. Reconciliation of sea-level observations in the Western North Atlantic during the last glacial cycle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 217, 171–181 (2003).

Creveling, J. R., Mitrovica, J. X., Clark, P. U., Waelbroeck, C. & Pico, T. Predicted bounds on peak global mean sea level during marine isotope stages 5a and 5c. Quat. Sci. Rev. 163, 193–208 (2017).

Raymo, M. E., Mitrovica, J. X., O/’Leary, M. J., DeConto, R. M. & Hearty, P. J. Departures from eustasy in Pliocene sea-level records. Nat. Geosci. 4, 328–332 (2011).

Lisiecki, L. E. & Raymo, M. E. Diachronous benthic δ18O responses during late Pleistocene terminations. Paleoceanography 24, 1–14 (2009).

Shakun, J. D., Lea, D. W., Lisiecki, L. E. & Raymo, M. E. An 800-kyr record of global surface ocean delta18O and implications for ice volume-temperature coupling. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 426, 58–68 (2015).

Dalton, A. S., Finkelstein, S. A., Barnett, P. J. & Forman, S. L. Constraining the Late Pleistocene history of the Laurentide Ice Sheet by dating the Missinaibi Formation, Hudson Bay Lowlands, Canada. Quat. Sci. Rev. 146, 288–299 (2016).

Sheridan, R. E. et al. Offshore-onshore correlation of upper Pleistocene strata, New Jersey Coastal Plain to continental shelf and slope. Sediment. Geol. 134, 197–207 (2000).

Dejong, B. D. et al. Pleistocene relative sea levels in the Chesapeake Bay region and their implications for the next century. GSA Today 25, 4–10 (2015).

Lisiecki, L. E. & Raymo, M. E. A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records. Paleoceanography 20, 1–17 (2005).

Dannenmann, S., Linsley, B. K., Oppo, D. W., Rosenthal, Y. & Beaufort, L. East Asian monsoon forcing of suborbital variability in the Sulu Sea during Marine Isotope Stage 3: link to Northern Hemisphere climate. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 4, 1001 (2003).

Cutler, K. B. et al. Rapid sea-level fall and deep-ocean temperature change since the last interglacial period. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 206, 253–271 (2003).

Shackleton, N. J. The 100,000-year ice-age cycle identified and found to lag temperature, carbon dioxide, and orbital eccentricity. Science 289, 1897–1902 (2000).

Pahnke, K., Zahn, R., Elderfield, H. & Schulz, M. 340,000-year centennial-scale marine record of southern hemisphere climatic oscillation. Science 16, 10-1–10-8 (2003).

Huybers, P. & Wunsch, C. A depth-derived Pleistocene age model: Uncertainty estimates, sedimentation variability, and nonlinear climate change. Paleoceanography 19, PA1028 (2004).

Simms, A. R., DeWitt, R., Rodriguez, A. B., Lambeck, K. & Anderson, J. B. Revisiting marine isotope stage 3 and 5a (MIS3-5a) sea levels within the northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Glob. Planet. Change 66, 100–111 (2009).

Curry, B. B. Absence of glaciation in illinois during Marine Isotope Stages 3 through 5 Quat. Res. 46, 19–26 (1996).

Colgan, P. M., Vanderlip, C. A. & Braunschneider, K. N. Athens Subepisode (Wisconsin Episode ) non-glacial and older glacial sediments in the subsurface of southwestern Michigan, USA. Quat. Res. 84, 382–397 (2015).

Acknowledgements

T.P. was supported by the NSF-GRFP and the Harvard University. J.R.C. acknowledges a donation from the G. Unger Vetlesen Foundation to Oregon State University. J.X.M. was funded by the Harvard University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.P. conducted the simulations and analysed the results. J.R.C., J.X.M. and T.P. conceived the project. All authors contributed extensively to this work. T.P. and J.X.M. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes, Supplementary Tables, Supplementary Figures and Supplementary References (PDF 566 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Pico, T., Creveling, J. & Mitrovica, J. Sea-level records from the U.S. mid-Atlantic constrain Laurentide Ice Sheet extent during Marine Isotope Stage 3. Nat Commun 8, 15612 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15612

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15612

This article is cited by

-

Rapid Laurentide Ice Sheet growth preceding the Last Glacial Maximum due to summer snowfall

Nature Geoscience (2024)

-

Reply to: Towards solving the missing ice problem and the importance of rigorous model data comparisons

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Giant clam (Tridacna) distribution in the Gulf of Oman in relation to past and future climate

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

A new global ice sheet reconstruction for the past 80 000 years

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Fast and slow components of interstadial warming in the North Atlantic during the last glacial

Communications Earth & Environment (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.