Abstract

Seeds respond to multiple different environmental stimuli that regulate germination. Nitrate stimulates germination in many plants but how it does so remains unclear. Here we show that the Arabidopsis NIN-like protein 8 (NLP8) is essential for nitrate-promoted seed germination. Seed germination in nlp8 loss-of-function mutants does not respond to nitrate. NLP8 functions even in a nitrate reductase-deficient mutant background, and the requirement for NLP8 is conserved among Arabidopsis accessions. NLP8 reduces abscisic acid levels in a nitrate-dependent manner and directly binds to the promoter of CYP707A2, encoding an abscisic acid catabolic enzyme. Genetic analysis shows that NLP8-mediated promotion of seed germination by nitrate requires CYP707A2. Finally, we show that NLP8 localizes to nuclei and unlike NLP7, does not appear to be activated by nitrate-dependent nuclear retention of NLP7, suggesting that seeds have a unique mechanism for nitrate signalling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Seeds sense and respond to environmental cues such as nitrate, light, after-ripening and temperature and these determine whether the environmental conditions are suitable for germination. A transcriptome analysis revealed that different germination stimuli trigger a similar transcriptome pattern1. This suggests that these environmental factors regulate a common downstream event, such as plant hormone action. Abscisic acid (ABA) and gibberellins (GA) regulate seed germination antagonistically in many plant species including Arabidopsis. Consistently, ABA and GA metabolism and signalling respond to changing environmental factors and induce downstream events suitable for the given environment. Seed germination is negatively regulated by ABA, which accumulates at high levels in the dry seed, and thus must be degraded for germination to occur2. The ABA 8′-hydroxylase, CYP707A, plays a key role in ABA catabolism in various plant responses3. In Arabidopsis, CYP707A1 and CYP707A2 have distinct roles in regulating seed dormancy and germination. CYP707A1 plays a role in the degradation of ABA that occurs during the mid-maturation stage of seed development. In contrast, CYP707A2 is expressed during the late-maturation stage of seed development, and becomes highly expressed after seed imbibition occurs4. Mutants of cyp707a1 over-accumulate ABA in the dry seed, while those of cyp707a2 accumulate only slightly higher levels of ABA in the dry seed, and show a defect in the ability to reduce ABA content once seed imbibition has occurred. Both mutants maintain a higher ABA content for a more prolonged period of time during seed imbibition when compared with the wild type, and are thus hyper-dormant. The expression of CYP707A2 is controlled by germination-related signals, suggesting that CYP707A2 acts as a hub for environmental signalling in germinating seeds5,6,7. Despite this, not much is known about how the expression of CYP707A2 is regulated by environmental factors.

Nitrate is the primary nitrogen source for plants and is assimilated to nitrite, ammonium and amino acids8. Nitrate reductase (NR) catalyses the conversion of nitrate to nitrite, the committed step of nitrate assimilation. In addition, nitrate acts as a signal molecule in that it induces a rapid shift in transcriptomes, even at low concentrations9. Nitrate regulates numerous aspects of plant developmental processes such as seed germination, root architecture and flowering10,11,12. Nitrate promotes seed germination independently of its reduction by NR, indicating it acts as a signal10,11. In addition to nitrate, other nitrogen-containing compounds such as nitrite, nitric oxide (NO) and cyanides also promote Arabidopsis seed germination13. A pharmacological experiment showed that nitrate promotion of Arabidopsis seed germination was blocked by 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (cPTIO), an NO-specific scavenger14. On the basis of this result, it was argued that nitrate promotion of seed germination is mediated by NO signalling. However, this result assumes that nitrate acts in a linear pathway that is upstream of NO signalling, and not in parallel or distinct pathways. Recently, Gibbs et al. reported that to promote germination, NO action requires the N-end rule proteasome pathway15. Identification of the nitrate signalling components in seeds, is crucial for evaluating the mechanism of nitrate action on germination in relation to other germination stimulating signalling pathways including NO.

In Arabidopsis, several regulators for nitrate signalling have been identified. Chlorate-resistant1 (CHL1, NRT1.1, NPF6.3) is a dual-affinity nitrate transporter and also acts as a nitrate sensor that is able to sense a wide range of nitrate concentrations through the phosphorylation of T101 (ref. 16). Several transcription factors including Arabidopsis nitrate regulated 1 (ANR1), Teosinte branched1/cycloidea/proliferating cell factor1-20 (TCP20) and NIN-like protein (NLP) have been shown to be involved in nitrate responses17,18,19,20. ANR1 is a MADS-box transcription factor controlling the growth of lateral roots and is believed to act downstream of CHL1 in response to a locally enriched nitrate source17,21. In contrast, TCP20 has been implicated in systemic nitrate signalling18. Recently, NLPs have been shown to play a central role in nitrate-regulated gene expression, nitrate assimilation and nitrate-induced growth promotion20,22. NLPs have been shown to directly bind to the nitrate-responsive cis-element (NRE) to induce nitrate-mediated transcription20. The N-terminal region of NLP6 acts as a nitrate-dependent transcriptional activation domain20. The nlp7 mutants display nitrate-starvation phenotypes when nitrate is used as the only nitrogen source19. Interestingly, nitrate regulates NLP7 by mediating its localization and retention in the nucleus. Primary nitrate-responsive genes such as those responsible for nitrate transport (for example, NRT1.1, NRT2.1) and assimilation (for example, NIA1, NIA2) are common direct targets of NLPs and TCP20 (refs 18, 22). However, it remains unknown how the upstream signalling influences a wide range of nitrate responses.

Here we report the identification and characterization of NLP8 in nitrate-promoted seed germination. Our research indicates that NLP8 regulates nitrate-promoted germination and directly activates expression of CYP707A2, an ABA catabolic enzyme. In addition, our research also suggests that NLP8 is activated by nitrate signalling by a distinct mechanism from the control of NLP7 by nitrate-dependent nuclear retention. The role and mechanism of NLP8-mediated regulation of nitrate-promoted seed germination is discussed.

Results

NLP8 is required for nitrate-promoted seed germination

Columbia (Col-0) wild-type seeds of Arabidopsis are dormant when harvested from plants grown at 16 °C (refs 23, 24). The dormant Col-0 seeds did not germinate when imbibed in water, but germinated in the presence of 1 mM KNO3. We utilized this system to investigate the nitrate response in seed germination. We previously reported that nitrate-induced gene expression occurs in 6-h imbibed seeds25. Therefore, we hypothesized that seeds imbibed for a short period of time (within 6 h), contain all components necessary for nitrate signalling. On the basis of the microarray data from seeds imbibed for <6 h (ref. 26), we selected candidate regulators for nitrate signalling in seeds and analysed whether or not corresponding T-DNA insertion mutants displayed nitrate-induced seed germination. Among the mutant lines examined, mutants defective in NIN-like protein8 (NLP8; At2g43500) did not germinate in the presence of 1 mM KNO3.

The Arabidopsis thaliana genome encodes nine NLP family members27. Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT–PCR) analysis showed that NLP8 was highly induced in imbibed seeds and the most abundantly expressed NLPs in 6-h imbibed seeds (Fig. 1a). Expression analysis also showed that nitrate does not regulate the mRNA level of NLP8 during seed germination (Supplementary Fig. 1). The nlp8 (nlp8-1 to nlp8-4) and nlp9 (nlp9-1 and nlp9-2) seeds of Col-0 background grown at 16 °C were used for germination tests (Fig. 1b). Col-0 and nlp9 mutants showed nitrate-promoted germination, however four nlp8 alleles did not (Fig. 1c). The nlp8-2nlp9-1 double mutant showed no germination in the presence of KNO3 (Fig. 1c). These results indicate that NLP8 is required for nitrate-promoted seed germination.

(a) Relative expression level of NLPs in dry seeds (white bar) and 6-h imbibed Col-0 seeds (black bar) from 16 °C. Transcript levels were normalized to the Col-0 genomic DNA and are shown by a mean±s.d. (n=4). *P<0.05; **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test compared with the relative expression in dry seeds). (b) Locations of T-DNA insertions in the NLP8 and NLP9. (c) Germination of nlp8 and nlp9 mutants in the presence of nitrate. Wild type, nlp8, nlp9, nlp8-2nlp9-1 mutants of Col-0 background were grown at 16 °C, harvested, and stored for 2 weeks at room temperature. Seeds were imbibed in water with 1 mM KCl (white bar) or KNO3 (lined bar) for 7 days. Percentage of germination is shown by a mean±s.d. (n=3). Note that all samples did not germinate in water with 1 mM KCl, thus the white bars are invisible. (d) Germination of nlp8 mutants of Ws-4 and Cvi backgrounds in the presence of nitrate. Seeds were harvested from plants grown at 22 °C. Freshly harvested Ws-4 and nlp8-5, and 2-month stored Cvi and nlp8-2/Cvi were used for germination tests. Seeds were imbibed in water with 1 mM KCl (white bar) or KNO3 (lined bar) for 7 days. Percentage of germination is shown by a mean±s.d. (n=3). **P<0.01 (Student t-test compared with corresponding wild type).

We then investigated whether the role of NLP8 was conserved across accessions. Wassilewskija-4 (Ws-4) and Cape Verde Islands (Cvi) accessions produce dormant seeds even harvested from plants grown at 22 °C. Seeds of Ws-4 wild-type and nlp8-5 mutant in the Ws-4 background harvested from plants grown at 22 °C were tested to determine whether germination could be promoted by nitrate (Fig. 1b). Ws-4 seeds, but not nlp8-5 seeds, responded to nitrate (Fig. 1d). We then tested the effect of the nlp8 mutation in the Cvi background. nlp8-2 was crossed to Cvi and near-isogenic lines were isolated after four backcross generations for the nlp8-2 mutation in the Cvi background (nlp8-2/Cvi) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Germination tests were performed using nlp8-2/Cvi and Cvi seeds. We found that the nlp8-2 mutation reduced the seed nitrate response in the Cvi background (Fig. 1d), showing that the requirement for NLP8 in nitrate-promoted germination is conserved across Arabidopsis accessions.

NLP8 is involved in nitrate signalling during germination

To examine the specificity of the nlp8 mutant phenotype to nitrate, the effect of stratification was tested. Stratified nlp8-1, nlp8-2 and nlp8-2nlp9-1 were able to germinate without application of KNO3, which was similar to that of the wild type (Supplementary Fig. 3). This indicates that nlp8 mutants are able to respond to the stratification treatment.

NR mutants are defective in both nitrate assimilation and nitric oxide (NO) production28,29. To distinguish if the effect of NLP8 on nitrate-regulated germination is triggered by direct nitrate signalling or nitrate assimilation and its products, nlp8-2nia1nia2 and nlp9-1nia1nia2 triple mutants were made. Germination of the nia1nia2 and nlp9-1nia1nia2 mutants was promoted upon application of nitrate (Fig. 2a). However, the nlp8-2nia1nia2 triple mutant did not respond to nitrate (Fig. 2a). This indicates that the role of NLP8 in nitrate-promoted germination involves nitrate signalling, rather than nitrate assimilation or NO production. NO-induced seed germination was shown to be mediated by the N-end rule proteasome degradation pathway, and two enzymes, Proteolysis 6 (PRT6) and Arg-tRNA protein transferase (ATE), were recently shown to be required for NO-promoted seed germination15. The prt6 and ate1ate2 mutants were still sensitive to nitrate-promoted seed germination (Fig. 2a), suggesting that the nitrate and NO signalling pathways are distinct from one another in seed germination.

(a) Germination of nia1nia2 nitrate reductase mutant (nia), nlp8-2nia1nia2 (nlp8-2nia) and nlp9-1nia1nia2 (nlp9-1nia) triple mutants, NO-insensitive ate1ate2 and prt6 mutants with or without nitrate. Percentage of germination is shown by a mean±s.d. (n=3). A white and lined bar indicates percentage of germination in water with 1 mM KCl and KNO3, respectively. (b) Nitrate dose responses of nitrate transceptor mutant lines, chl1-5, T101A/chl1-5 and T101D/chl1-5, and the nlp8-2 mutant during seed germination. Percentage of germination is shown by a mean±s.d. (n=3). Wild type, black; chl1-5, gray; T101A/chl1-5, green; T101D/chl1-5, blue; nlp8-2, white. *P<0.05; **P<0.01 (Student t-test compared with Col-0 wild type).

CHL1 was characterized as a nitrate sensor in Arabidopsis, and phosphorylation at T101 is important for nitrate transport and response16. The chl1 mutant was shown to be less sensitive to nitrate during seed germination10. Therefore, we compared the nitrate responsiveness between nlp8 and chl1 mutants during germination. The chl1-5 mutant contains a deletion that eliminates CHL1, while T101A/chl1-5 and T101D/chl1-5 lines contain the CHL1 mutant genes with T101A and T101D, respectively, in the chl1-5 mutant background16. chl1-5, T101A/chl1-5 and T101D/chl1-5 were tested for their nitrate response in seed germination. Similar to the previous report10, chl1-5 is less sensitive to nitrate-promoted seed germination compared with the Col-0 control (Fig. 2b). However, the insensitivity of chl1-5 to nitrate was only observed at low concentrations of nitrate, while nlp8-2 displayed a more prominent insensitivity to nitrate (Fig. 2b). This indicates that NLP8 regulates a wider range of nitrate responses than CHL1 does during seed germination. The negligible difference in germination phenotypes between chl1-5 and T101A/chl1-5 or T101D/chl1-5 suggested that the phosphorylation status of T101 of CHL1 has little effect on nitrate-promoted seed germination (Fig. 2b).

NLP8 regulates gene expression in response to nitrate

An RNA-seq experiment was performed using RNA extracted from Col-0 and nlp8-2 seeds imbibed for 6 h with 1 mM KNO3 or KCl (Supplementary Data 1). Forty seven upregulated genes and twenty-nine downregulated genes were identified in 6-h imbibed Col-0 seeds (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 4). Gene ontology (GO) term distribution indicates genes encoding transcription factors (eight genes, P=0.038) and related to nitrogen metabolism (six genes, P=6.47e-6) are overrepresented among those genes upregulated by nitrate. Some of the known nitrate-inducible genes such as NIA1, NIA2, nitrite reductase1 (NIR1), root-type Ferredoxin:NADP(H) Oxidoreductase1 (RFNR1), RFNR2, Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase2 (G6PD2) and G2-like transcription factor (AT1G25550) were included in the upregulated genes. In addition as we previously reported, CYP707A2, the main ABA catabolic gene during seed germination, was induced by nitrate. No other genes related to ABA and GA metabolism and signalling were found among the list of nitrate-regulated genes (Supplementary Fig. 5). Nitrate-mediated upregulation of almost all of the nitrate-inducible genes identified by RNA-seq, was absent or was significantly decreased in the nlp8-2 mutant (Fig. 3a). This was also true for the nitrate downregulated genes. Expression of some genes was further analysed by qRT–PCR to examine their expression kinetics on imbibition in the seed. When Col-0 seeds were imbibed in water with KCl, the expression of CYP707A2 increased and then decreased, with its maximum expression at 6 h (Fig. 3b). The expression of CYP707A2 in imbibed Col-0 seeds was induced by KNO3 with similar kinetics but at a higher level to that observed for the KCl-treated seeds. CYP707A2 had a much lower level of expression of in nlp8-2 in both KCl and KNO3 imbibed seeds. Importantly, nitrate had no effect on the expression of CYP707A2 in nlp8-2 (Fig. 3b). This was also found to be true for the expression of NIA2 (Fig. 3c). In addition, the expression of another eight genes were analysed by qRT–PCR and we observed expression patterns consistent with the RNA-seq data (Supplementary Figs 6 and 7).

(a) Nitrate-upregulated (left) and downregulated (right) genes in 6-h imbibed seeds in Col-0 or the nlp8-2 mutant. Seeds were imbibed in water with 1 mM KCl or KNO3 for 6 h and RNA was extracted for RNA-seq. The readouts from KNO3-treated seeds were normalized to those from KCl control and a mean of two biological repeats was used to generate a heatmap. (b,c) qRT–PCR expression analysis of CYP707A2 (b) and of NIA2 (c) in Col-0 and nlp8-2 seeds. The transcript levels were normalized to the expression level of At1g13320 and are shown by a mean±s.d. (n=3). Col-0 imbibed in KCl, black circle with solid line; Col-0 imbibed in KNO3, red circle with solid line; nlp8-2 imbibed in KCl, black square with dotted line; nlp8-2 imbibed in KNO3, red square with dotted line. *P<0.05, **P <0.01; Student’s t-test compared with the relative expression without nitrate in the same genotype.

NLP8 regulates ABA catabolism and induces CYP707A2

To determine whether the nitrate-induced decline in ABA contents is NLP8-dependent, the ABA content was measured in dry seeds and imbibed seeds of Col-0 and nlp8-2 with 1 mM KCl or KNO3 (Fig. 4a). In Col-0 seeds, the nitrate-induced ABA decrease was observed at 9 h after the onset of imbibition, and the ABA content in KNO3-treated seeds was lower than those in KCl-treated seeds thereafter (Fig. 4a). On the other hand, the ABA content in KNO3-treated nlp8-2 seeds was comparable to that seen in the KCl-treated nlp8-2 seeds, which was equivalent to that in KCl-treated Col-0 seeds (Fig. 4a). This indicates that the ABA decrease by nitrate is NLP8-dependent. The aba2 mutant line, which has a defect in ABA biosynthesis, was non-dormant even when harvested from 16 °C, and was able to germinate in the absence of nitrate (Fig. 4b). aba2 was found to be epistatic to nlp8-2 since aba2nlp8-2 germinated even without nitrate, showing that de novo ABA biosynthesis is required for nlp8-2 to establish seed dormancy. Col-0 and cyp707a1 responded to nitrate, while cyp707a2 was less sensitive to nitrate (Fig. 4b). Nitrate-promoted germination was not observed in the cyp707a1nlp8-2 and cyp707a2nlp8-2 double mutants (Fig. 4b). It is noteworthy that nitrate-independent expression of CYP707A2 in nlp8-2 by introducing the 35S::CYP707A2 caused nitrate-independent germination (Fig. 4b). Taken together, these results suggest that NLP8-mediated induction of CYP707A2 promotes seed germination in response to nitrate.

(a) Quantification of ABA contents in Col-0 and nlp8-2 seeds. Seeds were imbibed in water with 1 mM KCl or KNO3 for the indicated time periods. The ABA content was measured by liquid chromatography equipped with a mass spectrometry. Measurements were performed using three biological replicates, and a mean is shown with s.d. (n=3). Bold and dotted lines indicate Col-0 and nlp8-2, and black and red lines indicate KCl- and KNO3-treated seeds. * and ** indicate the significant differences with P<0.05 and P<0.01 (Student’s t-test compared with the ABA level in KCl-treated samples of the same genotype), respectively. (b) Germination of ABA metabolism and nlp8 mutants in the presence of nitrate. Col-0, aba2, cyp707a1, cyp707a2 and double mutants with nlp8-2 and 35S::CYP707A2 expressed in nlp8-2 (35SA2nlp8) were imbibed in water without (white bars) or with 1 mM nitrate (lined bars). Percentage of germination is shown by a mean±s.d. (n=3). * and ** indicate the significant differences from that of corresponding wild type, with P<0.05 and P<0.01 (Student’s t-test), respectively.

To test whether CYP707A2 is a direct target of NLP8, a 1.9-kb 5′ non-coding region of CYP707A2 was cloned, fused to a GUS reporter gene (A2-GUS), and transformed into Col-0 (Fig. 5a). The A2-GUS seeds from 16 °C grown plants were tested for nitrate-induced reporter expression by qRT–PCR. The expression of the native CYP707A2 served as a positive control for measuring nitrate-induction of the reporter gene expression. A2-GUS lines (#1 and #6) displayed nitrate-induced reporter expression similar to the native CYP707A2 (Fig. 5b). Next, a promoter deletion series were made and fused to the GUS reporter gene to identify the promoter region responsible for nitrate induction (Fig. 5a). These promoter deletion constructs, d1-GUS to d3-GUS, were transformed into Col-0 and selected transgenic lines were grown at 16 °C. The d1-GUS (−1,661) line showed nitrate-induced reporter expression that was similar to the A2-GUS lines. In contrast, the d2-GUS (−1,373) and d3-GUS (−741) lines did not show nitrate-induced reporter expression (Fig. 5b). This indicates that the region between −1,661 and −1,373 is responsible for the nitrate-mediated induction of CYP707A2.

(a) The CYP707A2 promoter-GUS constructs and the fragments used for ChIP analysis (1 to 6). (b) Promoter deletion analysis of CYP707A2 for identifying promoter regions responsible for nitrate induction. qRT–PCR analysis of GUS reporter expression in 6-h imbibed seeds of promoter-GUS transgenic lines. The GUS transcript level in 10 mM KNO3-treated seeds was normalized to that in 10 mM KCl-treated seeds (black bar). The dotted line indicates the value 1 (that is, no nitrate induction). Nitrate induction of native CYP707A2 was used as a positive control (white bar). Data shown are means±s.e. (n≥3). **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test). (c) ChIP analysis of the CYP707A2 promoter using 35S::NLP8-GFP line. White bars and lined bars indicate the ChIP data from KCl-treated and KNO3-treated plants, respectively. Signals obtained from the anti-GFP sample (+Ab) were normalized to those from the no antibody control (−Ab). The dotted line indicates the value 1 (that is, no enrichment). Data shown are means±s.d. (n=4). *P<0.05; **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test compared with corresponding KCl-treated samples). (d) A 41-bp region in the CYP707A2 promoter required for nitrate induction, and three mutations introduced. (e) NLP8-dependent activation of the reporter (LUC) gene expression driven by mutant promoters in a protoplast system. NLP8-GFP and ACT2 (control) were transiently expressed in protoplasts in the presence of nitrate. LUC activities were normalized by GUS activities from co-introduced 35S::GUS. Averages of reporter activities of NLP8-GFP expressed protoplasts (lined bar) and ACT2 expressed protoplasts (white bar) with s.d. are shown (n=3). **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test). (f) Specific binding of the RWP-RK domain of NLP8 to the NRE of the CYP707A2 promoter. A biotin-labelled probe containing two copies of d1-d1.5 (1.5 ng) and RWP-RK domain of NLP8 (200 ng) were used for EMSA reactions and separated in a 5% native PAGE gel. Competitors were two copies of d1-d1.5 or d1.4-d1.5 fragments without biotin labeling (+: 50-fold, ++: 100-fold). A red star indicates the shifted band, while the black star indicates the signal from free probe.

We next generated 35S::NLP8-GFP transgenic lines. Six DNA fragments spanning CYP707A2 as shown in Fig. 5a, were examined by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). The co-immunoprecipitated DNA was analysed by quantitative PCR. Relative fold enrichment was calculated by normalizing the value of immunoprecipitated anti-GFP fragments to that of the control sample that did not contain any antibody. Fragments #1 (−1,661 to −1,552) and #2 (−1,549 to −1,383) showed enrichment, but not fragments #3 to #6, in nitrate-treated samples (Fig. 5c), demonstrating a direct binding of NLP8 to these fragments in the promoter region of CYP707A2. Such enrichments were not observed in the KCl-treated samples (Fig. 5c). These results collectively suggest that NLP8 directly binds to the promoter of CYP707A2 in a nitrate-dependent manner and upregulates its expression during seed germination in the presence of nitrate.

A protoplast assay was employed to further narrow down the promoter region responsible for NLP8-dependent expression of CYP707A2. A series of promoter deletions fused to a LUC reporter gene were tested for their nitrate induction when co-transformed with the 35S::NLP8-GFP construct. Two positive controls, A2-LUC and d1-LUC(−1,661), showed the NLP8-dependent nitrate response in the protoplast assay similar to that observed in the A2-GUS and d1-GUS stable transgenic lines (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 8). Nitrate-induced reporter expression was also observed in d1.2-LUC(−1,638), d1.3-LUC(−1,615) and d1.4-LUC(−1,589) but not in d1.5-LUC(−1,549) (Supplementary Fig. 8), indicating that the 41 bp region between d1.4 and d1.5 is responsible for NLP8-dependent nitrate induction (Fig. 5d).

To identify the NLP8-binding sites, mutations were introduced to d1.4-LUC and the NLP8-dependent reporter expression was analysed in the presence of nitrate in the protoplast assay (Fig. 5d,e). d1.4-LUC with disruptions of single sites (1m, 2m, 3m) and double sites (1m2m, 1m3m) still responded to NLP8, but the d1.4-LUC with all three sites mutated (1m2m3m) did not respond (Fig. 5e). This result suggests that these three sites are required for NLP8-dependent gene expression.

We next performed an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) to verify the physical interaction between NLP8 and the promoter of CYP707A2. The binding of the RWP-RK domain of NLP8 to the d1-d1.5 fragment resulted a shifted band in the EMSA (Supplementary Fig. 9a). The application of nitrate did not affect its binding (Supplementary Fig. 9a). The shifted band disappeared by addition of competitor d1.4-d1.5 (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 9a), but mutant competitor with all three sites disrupted failed to compete (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 9b). These collectively indicate that NLP8 binds to these three sites in the CYP707A2 promoter.

Nitrate activates NLP8 and NLP7 via distinct mechanisms

A 35S::NLP8-GFP construct was introduced into nlp8-2 by crossing them together, and the homozygous lines for both 35S::NLP8-GFP and the nlp8-2 mutation were selected for and designated as NLP8-GFP nlp8-2. NLP8-GFP nlp8-2 was able to germinate in the presence of nitrate (Fig. 6a), showing that NLP8-GFP complemented nlp8-2. It was also found that the constitutive expression of NLP8-GFP did not confer nitrate-independent germination, but that germination of NLP8-GFP nlp8-2 still required nitrate. NLP8-GFP also failed to alleviate the weak reduced nitrate sensitivity phenotype of chl1-5 (Supplementary Fig. 10). Interestingly, the double homozygous line for 35S::NLP7-GFP and the nlp8-2 mutation, NLP7-GFP nlp8-2, failed to complement the nlp8-2 mutation (Fig. 6a). This suggests that NLP7 and NLP8 have distinct functions from one another. To test whether the subcellular localization of NLP8 is under the control of nitrate like it is the case for NLP7, germinated seedlings of 35S::NLP8-GFP and 35S::NLP7-GFP were observed using confocal microscopy to examine subcellular localization of GFP signals with or without nitrate. The GFP signal of the NLP7-GFP was localized to the cytoplasm in the absence of nitrate, and with the application of nitrate became nuclear localized within a few minutes (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Movie 1), as reported in (ref. 22). In contrast, NLP8-GFP was localized in the nuclei regardless of nitrate application (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Movie 2). This suggests that nitrate may activate NLP8 by a different mechanism from that of NLP7.

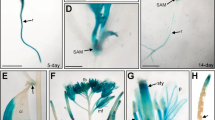

(a) Complementation of nlp8-2 by 35S::NLP8-GFP, but not by 35S::NLP7-GFP. Percentage of germination is shown by a mean±s.d. (n=3). (b) Subcellular localization of NLP8-GFP and NLP8N-LexA_DB-YFP in the stomata of KCl- or KNO3-treated cotyledons. NLP7-GFP was used as a control for the nitrate-regulated nuclear retention. A bar indicates 10 μm. (c) Schematic diagram of effector construct (NLP8N-LexA_DB-YFP) harboring the N-terminal region of NLP8 (NLP8(N)), LexA DNA-binding domain (LexA_DB) and YFP, while the reporter is GUS driven by eight copies of LexA operon fused to 35S minimal promoter (LexAOP-35Smini::GUS). (d) GUS staining of transgenic lines harbouring both effector (NLP8N-LexA_DB-YFP) and reporter (LexAOP-35Smini::GUS). Left panel, 10 mM KCl- and KNO3-treated 18-h-imbibed embryos; middle panel, cotyledons of 7-day-old seedlings treated with 3 mM KCl and KNO3; guard cells at the cotyledons of 7-day-old seedlings treated with 3 mM KCl and KNO3. From left to right, bars indicate 100, 100 and 20 μm.

The N-terminal region of NLP6 was shown to function as a nitrate-dependent transcriptional activation domain20. The N-terminal region (1–576 amino acids) of NLP8 was fused to the LexA DNA-binding domain (LexA_DB) to make the NLP8N-LexA_DB-YFP effector. The NLP8N-LexA_DB-YFP chimeric transcription factor construct was transformed together with the reporter, LexAOP-35Smini::GUS, into Col-0 plants (Fig. 6c). Similar to NLP8-GFP, NLP8N-LexA_DB-YFP also localized to the nuclei with or without nitrate application (Fig. 6b). Transgenic plants containing both chimeric constructs were examined for reporter expression. Seven-day-old nitrate-starved seedlings and imbibed seeds displayed nitrate-dependent GUS reporter expression (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 11). It is worth noting that, before application of nitrate, NLP8-YFP is localized in nuclei in the guard cells of cotyledons (Fig. 6b), and this cell type is competent (or contains components necessary) to trigger NLP8-dependent nitrate inducible gene expression (Fig. 6d). Taken together, these data indicate that the N-terminal region is responsible for induction of NLP8 by nitrate and NLP8-dependent nitrate signalling is unlikely to involve nitrate-dependent change in protein localization.

Discussion

Nitrate is an important germination stimulator for many plant species, although its mode of action in seeds is poorly understood. This study identified NLP8 as a key regulator for nitrate signalling during germination. Transcriptome analysis indicates that NLP8 primarily activates the expression of nitrate-inducible transcription factors, and nitrogen metabolism enzymes (Fig. 3a), acting as a primary nitrate regulator to trigger secondary responses. Notably, time course expression analysis showed that NLP8-dependent nitrate induction is transient and is not seen in 12-h imbibed seeds (Fig. 3b,c), suggesting that a repressive mechanism comes into play to downregulate expression of NLP8-reglated genes in the latter stages of seed imbibition.

On the basis of our results, we propose that NLP8-dependent induction of CYP707A2 regulates seed germination. The cyp707a2 mutant displays reduced nitrate responsiveness, while nitrate-independent induction of CYP707A2 in the nlp8-2 mutant led to nitrate-independent germination (Fig. 4b), consistent with the notion that CYP707A2 is an important downstream target of NLP8 in terms of germination control. The decrease of ABA by CYP707A2 is initiated in Phase I (ref. 26), which is well correlated with the temporal pattern of NLP8-dependent nitrate induction. The NLP8-dependent decrease of ABA is comparable to changes in ABA levels observed in light-regulated and temperature-regulated Arabidopsis seeds, suggesting that this difference in ABA levels is physiologically relevant30,31. We did not detect regulation of NLP8 expression by nitrate (Supplementary Fig. 1), but activation of NLP8 signalling by nitrate induced the expression of CYP707A2 (Figs 3 and 6). Cycloheximide-resistant gene expression is a characteristic feature that has been observed in Phase I (ref. 32), which is also consistent with the mode of NLP8 action. GA biosynthesis is activated in Phase II, which is associated with the initiation of germination31. It is known that the decrease in ABA levels is a prerequisite for the proper function of GA during Arabidopsis germination2. Therefore, it is likely that the NLP8-mediated induction of CYP707A2 affects the germination control in Phase II, which includes the control of GA biosynthesis and sensitivity. In addition, it cannot be rule out that NLP8 influences seed germination via CYP707A2-independent pathway. Because some genes encoding transcription factors are nitrate-induced in an NLP8-dependent manner (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 4), it is possible that these transcription factors contribute to nitrate-promoted germination independently of CYP707A2. It is a future challenge to elucidate the secondary nitrate response triggered by NLP8 to fully understand nitrate-promoted seed germination.

The nlp8 mutants display prominent phenotypes in nitrate-dependent germination. Nitrate-promoted seed germination of the nia1nia2 mutant is NLP8-dependent (Fig. 2a), which indicates NLP8 acts in the nitrate signalling pathway to promote seed germination. The chl1 mutant also displays nitrate insensitive germination10, but its phenotype is much milder than that of the nlp8 mutant (Fig. 2b). In addition, only a negligible effect of the phosphor-mimic and phosphor-dead CHL1 mutant was observed on nitrate-promoted germination (Fig. 2b). This is consistent with the notion that CHL1 plays a minor role in the control of seed germination, and other nitrate sensor(s) might contribute to the NLP8-dependent germination control in the seeds.

We found 55 downregulated and 115 upregulated genes in the nlp8-2 mutant independent of nitrate application (Supplementary Data 1). Downregulated genes in nlp8-2 in the absence of nitrate induction include the highly nitrate-induced NLP8-dependent genes, such as NIA2, CYP707A2 and NIR1. Because the CYP707A2 transcript is downregulated in the dry seeds of nlp8-2 (Fig. 3b), it is likely that NLP8 functions not only during germination, but also during seed development. On the other hand, upregulated genes in the nlp8-2 mutant are enriched for those related to stresses, such as thiredoxin-dependent peroxidase2 (TPX2) and glutathione S-transferase1 (GST1) (Supplementary Fig. 6). It is possible that a defect in nitrate signalling induces a defense mechanism. In addition, nitrate-independent misexpressed genes in the nlp8 mutants include phytochrome interacting factor 3-like 5 (PIL5) and abscisic acid-insensitive 4 (ABI4) (Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Fig. 6). Downregulation of these genes is expected to promote seed germination, which is opposite to the phenotype of nlp8, suggesting the possibility of feedback regulation in response to the defect in seed nitrate signalling.

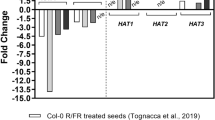

Multiple environmental signals must coordinately interact with one another in the seed to modulate downstream events1. Transcriptome analysis in this study revealed potential crosstalk between nitrate and light signalling during germination. Two transcription factors related to light response, HY5-homolog (HYH) and far-red impaired responsive1 (FAR1)-family protein, are under the control of NLP8 (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 4). NLP8 was listed in the genes directly regulated by PIL5, a key regulator for light signalling during germination in Arabidopsis33. Interestingly, PIL5 is missexpressed in the nlp8 mutant (Supplementary Fig. 6). PIL5 directly regulates GA signalling and indirectly regulates ABA and GA metabolism34. It is possible that crosstalk may occur between environmental signals and germination stimulants, to coordinately regulate seed dormancy and germination.

Nitrate promotion of seed germination was thought to be mediated by NO signalling13. However, our data presented in this study indicates that nitrate promotes germination by a distinct mechanism from that of NO signalling. The source of NO production is still unclear in plants, but it was reported that NO is produced by NO-associated protein 1 (NOA1) and NR in Arabidopsis. The nia1nia2 mutant was still capable of responding to nitrate and promoted germination in an NLP8-dependent manner, despite the fact that this mutant has only 0.5% of the wild-type NR activity and lower endogenous NO levels28,29. This suggests that nitrate promotes germination independently of its assimilation products (Fig. 2a). In addition, NO-insensitive mutants, prt6 and ate1ate2, are able to respond to nitrate during germination (Fig. 2a). This further supports that nitrate acts independently of NO signalling during seed germination.

Expression of NLP8 driven by the 35S promoter had no germination-promoting effect in the absence of nitrate (Fig. 6a) despite the fact that expression was two- to three-fold higher than wild type. This suggests that this level of overexpression itself has no obvious effect on the downstream events. However, it remains possible that this could be due to insufficient overexpression in particular cell or tissue types that would be required for a constitutive response. The 35S::NLP8-GFP and 35S::NLP8N-LexA_DB-YFP lines express GFP without nitrate application, suggesting that the NLP protein levels or its stability is not the primary regulation for NLP8 activation by nitrate. Post-translational activation of NLP6 and NLP7 functions were also reported. Overexpression of the NLP6-LexA construct did not transactivate the 8OP promoter, unless treated with nitrate20. Constitutive expression of NLP7 showed no additional effect except complementation of the poor growth phenotype of the nlp7 mutant19, suggesting that NLPs require additional factors or post-translational modifications to regulate the primary response to nitrate.

The localization or retention of NLP7 in nuclei is regulated by nitrate22. However, nitrate regulates the function of NLP8 differentially, since NLP8-GFP is localized to the nucleus in the absence of nitrate (Fig. 6b). It is noteworthy that stomata of cotyledons in which NLP8 is localized to the nucleus without nitrate treatment is competent to trigger an NLP8-dependent nitrate signalling (Fig. 6b,d). Therefore it is unlikely that nitrate-independent nuclear localization of NLP8 is due to the components of missing nitrate signalling caused by ectopic expression. In addition, another new finding is that binding of NLP8 to the CYP707A2 promoter in vivo is nitrate-dependent, even though NLP8 is localized to the nucleus before nitrate application (Figs 5c and 7). The inability of NLP7-GFP to complement nlp8-2 also supports the notion that NLP8 and NLP7 demonstrate distinct differences in regulation, due to differing functions. It has been argued that mechanisms of plant nitrate responses vary depending on developmental and environmental contexts, which is called ‘matrix effect35. Our findings indicate that multiple mechanisms that activate NLP functions form an essential component of complex nitrate responses in plants.

NLP8 is located in nuclei regardless of nitrate application. Nitrate activates NLP8 post-translationally, which facilitates DNA binding to the NREs in the promoters of nitrate-regulated genes in seeds, including CYP707A2. Nitrate-induction of CYP707A2 decreases the ABA content, which promotes seed germination.

Methods

Plant material and growth conditions

nlp8-1 (SALK_031064), nlp8-2 (SALK_140298), nlp8-3 (WiscDsLoxHs201_10C), nlp8-4 (SALK_026238), nlp9-1 (SALK_025839) and nlp9-2 (SALK_098057) were obtained from ABRC. nlp8-5 (FLAG_537A05) and Ws-4 were ordered from INRA. chl1-5, T101A/chl1-5 and T101D/chl1-5 (ref. 16), ate1ate2 and prt6 (ref. 15), 35S::NLP7-GFP19, nia1nia2 (nia1-1nia2-5)29, aba2 (aba2-2)36, cyp707a1 (cyp707a1-1)4 and cyp707a2 (cyp707a2-1)5 were described previously. All lines in Col-0 background were grown at 22 °C until flowering and then switched to 16 °C and continuous light for seed maturation. nlp8-5, Ws-4, nlp8-2/Cvi and Cvi were grown at 22 °C. For ChIP and microscope analysis, seeds were surface sterilized and stratified for 4 days and then sown on nitrate-free 1/2 MS medium containing 3 mM KCl (referred here as KCl plate) or KNO3 (referred here as KNO3 plate)22, for indicated periods of time.

Germination test

Seeds stored for 2 weeks to 3 months at room temperature were used for germination test. Approximately 50 seeds were soaked in 1 ml liquid media in a 24-well plate. Plates were incubated for 7 days at 23 °C under continuous white light condition (25 μmol m−2 s−1). Radicle protrusion was used as a criterion for germination.

Constructs and transformation

For 35S::NLP8-GFP, full-length CDS of NLP8 was amplified from cDNA synthesized from Col-0 seeds and cloned into the binary vector pGWB505 (ref. 37). Transcript levels of NLP8 in these transgenic lines were examined by qRT–PCR (Supplementary Fig. 12). To generate 35S::CYP707A2 lines, CYP707A2 cDNA containing 5′- and 3′-UTR were PCR amplified, cloned into pENTR/D/TOPO vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and subsequently cloned into the modified binary vector pGWB2, which contained the enhancer sequence and 35S promoter of pBE2113N between HindIII and XbaI sites37,38. For A2-GUS and promoter deletions, different lengths of the promoter region of CYP707A2 were amplified from Col-0 genomic DNA and cloned into the binary vector pMDC162 (ref. 39). For the transient assay, deletion and mutated CYP707A promoters were cloned into the binary vector pGWB535 (ref. 37). Mutated DNA fragment was generated by PCR-mediated site-directed mutagenesis. For the chimeric construct, NLP8N and LexA_DB was first amplified from 35S::NLP8-GFP and pER8 (ref. 40), respectively. NLP8N-LexA_DB translational fusion was amplified by overlap PCR, and cloned into binary vector pEarlygate101 (ref. 41). LexAOP-35Smini was amplified directly from pER8 and cloned into pMDC162. All constructs were sequence verified and transformed into Col-0 using the floral dip method. Primers are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

Protoplast transient assay

A luciferase (LUC) reporter activity driven by deletion and mutated CYP707A2 promoters were tested in a protoplast transient assay. 35S::NLP8-GFP and 35S::GUS (pCAMBIA1105.1R) were used as an effector and an internal control plasmid, respectively. Transfection-grade plasmids were isolated by FastGene Xpress Plasmid PLUS Kit (FastGene). Arabidopsis protoplasts were prepared from young rosette leaves of 3-week-old plants as previously described42. A reporter (7.5 μg), an effector (7.5 μg) and an internal control GUS plasmid (1 μg) were co-transfected into ∼2 × 104 protoplasts by a 20% w/v polyethylene glycol 4000-mediated method. In the non-effector experiment, the pMD20 (7.5 μg) plasmid containing ACT2 (AT3G18780) cDNA was used to adjust total amount of input DNA as a control. After transfection, cells were cultured with 0.5 M mannitol and 4 mM MES (pH 5.7) containing 20 mM KCl or KNO3 for 18 h at 22 °C. Cells were collected, and then LUC and GUS activities were measured using luciferase assay system kit (Promega) and 4-methylumbelliferyl-D-glucuronide (Sigma), respectively, as substrates. The relative promoter activity was determined by calculating ratios of LUC and GUS activities.

Expression analysis and ChIP

RNA was extracted from seeds imbibed in 1 mM KCl or KNO3 for 6 h. Briefly, total RNA was extracted by acid phenol extraction, precipitated with lithium chloride and DNase digested as previously described43. After DNA digestion, cDNA was synthesized using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Life Technologies). Paired-end RNA-seq was performed on Illumina GAIIx. qRT-PCR was performed using SsoFast EvaGreen supermixes (Bio-Rad) and a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). At1g13320 was used as the reference gene44,45. The biological replicates analysed were as follows: A2-GUS #1, n=3; A2-GUS #6, n=3; d1-GUS #3, n=4; d2-GUS #2, n=3; d2-GUS #6, n=5; d3-GUS #1, n=3; d3-GUS #11, n=3. The expression stability of this gene was confirmed by geNORM analysis (Supplementary Fig. 13)46. ChIP experiment was performed as the method described in Saleh et al.47 with minor modifications. Ten-day-old 35S::NLP8-GFP was grown on 3 mM KNO3 plates and then transferred to nitrate-free 1/2 MS liquid medium containing 3 mM KCl for 3 days, then resupplied with 10 mM KNO3 for 20 min. Approximately 0.5 g of seedlings were treated with the cross-linking buffer containing 1% formaldehyde, 0.4 M sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM EDTA and 10 mM KNO3 for 10 min. After sonication, DNA was recovered from the sample incubated with anti-GFP (A11122, Life Technologies) and Protein G Agarose Beads (#9007, Cell Signaling Technology). Experiments were done in four replicates and relative fold enrichment was calculated by normalizing the amount of a target DNA fragment against that of no antibody control.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

The RWP-RK DNA binding domain (amino acid 549–686) of NLP8 was PCR amplified and cloned into pET32a-LIC. Protein expression was induced by application of 1 mM IPTG to BL21 carrying pET32a-NLP8 when OD600 was 0.4, and incubated at 16 °C overnight. Protein was purified using HisPur Ni-NTA Spin Column (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manual. For preparing probes and competitors, single-strand oligonucleotides were annealed to form dsDNA. Two copies of tandem fragments were obtained through self-ligation after T4 polynucleotide kinase treatment. Probes and competitors were amplified by PCR using biotin labeled or non-labeled primers. EMSA was performed using LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and membrane was exposed to ChemiDocTM MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad). Around 1.5 ng biotin labelled probe and 200 ng NLP8 protein were used for each reaction. Competitors were 50-fold (+) or 100-fold (++).

CAPS marker design

The genome-wide SNP data of Col-0 and Cvi-0 was obtained from the AtSNPtile1 SNP datasets previously published48,49. The array information was updated to version TAIR10 based on the AtSNPtile1 probe sequences (http://aquilegia.uchicago.edu/naturalvariation/cisTrans/ArrayAnnotation.html) and TAIR10 sequence datasets (ftp://ftp.arabidopsis.org/home/tair). Pseudo BLAST alignments were constructed using this data set and TAIR10 genome sequence by replacing the bases in TAIR10 sequence by SNPs and formatting the alignment to match the BLAST output format. BlastDigester was run on these alignments after setting the ‘show only differential cutters’ option50. The output for BlastDigester was kept if DNA could be digested with the following enzymes: AccI, BamHI, BclI, BglI, BglII, SnaBI, EcoRV, EcoRI, HindIII, KpnI, NaeI, NdeI, NcoI, PstI, PvuII, SalI, SacI, SmaI, SpeI, XbaI and XhoI. CAPS markers are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

RNA-seq data processing

RNA-seq reads were aligned to Arabidopsis thaliana gene models (TAIR 10) using the short read mapping tool, novoalign (novocraft.com). The reads mapped to multiple locations were discarded. The reads mapped to each gene were counted and rpkm (reads per kilobase per million) was calculated using an in house php script. Differential gene expression was analysed with the R package DEGseq51. The replicates were compared by method FC (fold-change) with a cutoff of abs(log2(FC))<1.3219 for all replicate groups. The treatments (KCl versus KNO3) were compared by method MARS (MA-plot-based method with Random Sampling model) with a cutoff of P<0.001 for both Col-0 and npl8-2. A gene is differentially expressed between treatments only when its P value is below 0.001 and no significant change between the replicates is observed. RNA-seq set is presented in Supplementary Data 1. For making heatmap, genes differentially expressed by nitrate treatment at greater than two-fold change in Col-0 were selected to generate heatmap using GENE-E (http://www.broadinstitute.org/cancer/software/GENE-E/index.html). Overrepresentation of particular GO terms in nitrate-induced genes was judged by P values of the hypergeometric distribution, calculated as P=BC(M, x) × BC(N−M, n−x) BC(N, n)−1 with BC as the binominal coefficient, x as the number of nitrate-induced genes belonging to a particular GO category, n as the total number of nitrate-induced genes, M as the number of genes belonging to a particular GO category, and with N as the total number of genes in the Arabidopsis genome52.

Quantification of ABA contents

Dry seeds and imbibed seeds were collected and homogenized in 80% (v/v) methanol containing 1% (v/v) glacial acetic acid by TissueLyser (Qiagen). The internal standard was added and stored overnight at 4 °C.

Samples were centrifuged to remove debris, and the pellet was washed twice. The supernatant was evaporated in a SpeedVac, reconstituted in 1 ml of 1% (v/v) acetic acid. ABA and d6-ABA were purified by solid phase extraction using Oasis HLB, MCX and WAX cartridge columns (Waters) as previously described26. The solvent was removed under vacuum and subjected to the LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis (Agilent 6,410 TripleQuad LC/MS system). An LC (Agilent 1200 series) equipped with a 50 × 2.1 mm, 1.8-μm Zorbax SB-Phenyl column (Agilent) was used with a binary solvent system comprising 0.01% (v/v) acetic acid in water (Solvent A) and 0.05% (v/v) acetic acid in acetonitrile (Solvent B). Separations were performed using a gradient of increasing acetonitrile content with a flow rate of 0.2 ml min−1. The gradient was increased linearly from 3% B to 50% B over 15 min. The retention time of ABA was 14.0 min. MS/MS conditions were as follows: capillary 4.0 kV; source temperature, 100 °C; desolvation temperature, 350 °C; cone gas flow, 0 l min−1; desolvation gas flow, 12 l min−1; fragmentor, 140; collision energy, 8; cell accelerator voltage, 7; polarity, negative; MS/MS transition, 269/159 m/z for d6-ABA and 263/153 m/z for ABA. A calibration curve was made with d6-ABA and ABA.

Microscope imaging

Five-day-old 35S::NLP7-GFP or 35S::NLP8-GFP lines were grown on KNO3 plates and then transferred to KCl plate for 2 days. Nitrate was resupplied by transferring seedlings to filter paper soaked in nitrate-free 1/2 MS liquid medium containing 3 mM KCl or KNO3 for 20 min. Cotyledons were mounted in 40 μl 3 mM KCl or KNO3 and visualized with a Leica TCS SP5 Confocal microscope.

For the GUS staining, seven-day-old seedlings grown on KCl plates were transferred to filter paper and soaked in nitrate-free 1/2 MS liquid medium containing 10 mM KCl or KNO3 for 4 h or seeds were imbibed in 10 mM KCl or KNO3 for 18 h before GUS staining. The seedlings were imaged using the Olympus SZX7 stereo microscope, and the embryos were imaged using the Olympus BX51 Differential Interference Contrast microscope. For movies, plants were cultivated on 2.5 mM ammonium succinate for 7 days in long day, 3 mM nitrate was then added under the Zeiss LSM 710 Confocal. Pictures were taken every 3 s and combined to export as movie using ZEN 2012 lite software.

Data availability

RNA-seq data generated as part of this study have been deposited in the NCBI SRA database under accession code SRP082409. The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Files or are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Yan, D. et al. NIN-like protein 8 is a master regulator of nitrate-promoted seed germination in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 7, 13179 doi: 10.1038/ncomms13179 (2016).

References

Finch-Savage, W. E., Cadman, C. S., Toorop, P. E., Lynn, J. R. & Hilhorst, H. W. Seed dormancy release in Arabidopsis Cvi by dry after-ripening, low temperature, nitrate and light shows common quantitative patterns of gene expression directed by environmentally specific sensing. Plant J. 51, 60–78 (2007).

Nambara, E. et al. Abscisic acid and the control of seed dormancy and germination. Seed Sci. Res. 20, 55–67 (2010).

Nambara, E. & Marion-Poll, A. Abscisic acid biosynthesis and catabolism. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 56, 165–185 (2005).

Okamoto, M. et al. CYP707A1 and CYP707A2, which encode abscisic acid 8′-hydroxylases, are indispensable for proper control of seed dormancy and germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 141, 97–107 (2006).

Kushiro, T. et al. The Arabidopsis cytochrome P450CYP707A encodes ABA 8′-hydroxylases: key enzymes in ABA catabolism. EMBO J. 23, 1647–1656 (2004).

Footitt, S., Douterelo-Soler, I., Clay, H. & Finch-Savage, W. E. Dormancy cycling in Arabidopsis seeds is controlled by seasonally distinct hormone-signaling pathways. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20236–20241 (2011).

Footitt, S., Huang, Z. Y., Clay, H. A., Mead, A. & Finch-Savage, W. E. Temperature, light and nitrate sensing coordinate Arabidopsis seed dormancy cycling, resulting in winter and summer annual phenotypes. Plant J. 74, 1003–1015 (2013).

Crawford, N. M. Nitrate: nutrient and signal for plant growth. Plant Cell 7, 859–868 (1995).

Wang, R., Okamoto, M., Xing, X. & Crawford, N. M. Microarray analysis of the nitrate response in Arabidopsis roots and shoots reveals over 1,000 rapidly responding genes and new linkages to glucose, trehalose-6-phosphate, iron, and sulfate metabolism. Plant Physiol. 132, 556–567 (2003).

Alboresi, A. et al. Nitrate, a signal relieving seed dormancy in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 28, 500–512 (2005).

Hilhorst, H. W. M. & Karssen, C. M. Nitrate reductase independent stimulation of seed-germination in Sisymbrium officinale L (Hedge Mustard) by light and nitrate. Ann. Bot. 63, 131–137 (1989).

Fitter, A., Williamson, L., Linkohr, B. & Leyser, O. Root system architecture determines fitness in an Arabidopsis mutant in competition for immobile phosphate ions but not for nitrate ions. Proc. Biol. Sci. 269, 2017–2022 (2002).

Bethke, P. C., Libourel, I. G., Reinohl, V. & Jones, R. L. Sodium nitroprusside, cyanide, nitrite, and nitrate break Arabidopsis seed dormancy in a nitric oxide-dependent manner. Planta 223, 805–812 (2006).

Bethke, P. C., Libourel, I. G. & Jones, R. L. Nitric oxide reduces seed dormancy in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 517–526 (2006).

Gibbs, D. J. et al. Nitric oxide sensing in plants is mediated by proteolytic control of group. VII ERF transcription factors. Mol. Cell 53, 369–379 (2014).

Ho, C. H., Lin, S. H., Hu, H. C. & Tsay, Y. F. CHL1 functions as a nitrate sensor in plants. Cell 138, 1184–1194 (2009).

Zhang, H. & Forde, B. G. An Arabidopsis MADS box gene that controls nutrient-induced changes in root architecture. Science 279, 407–409 (1998).

Guan, P. et al. Nitrate foraging by Arabidopsis roots is mediated by the transcription factor TCP20 through the systemic signaling pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 15267–15272 (2014).

Castaings, L. et al. The nodule inception-like protein 7 modulates nitrate sensing and metabolism in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 57, 426–435 (2009).

Konishi, M. & Yanagisawa, S. Arabidopsis NIN-like transcription factors have a central role in nitrate signalling. Nat. Commun. 4, 1617 (2013).

Remans, T. et al. The Arabidopsis NRT1.1 transporter participates in the signaling pathway triggering root colonization of nitrate-rich patches. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 19206–19211 (2006).

Marchive, C. et al. Nuclear retention of the transcription factor NLP7 orchestrates the early response to nitrate in plants. Nat. Commun. 4, 1713 (2013).

Chiang, G. C. et al. DOG1 expression is predicted by the seed-maturation environment and contributes to geographical variation in germination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Ecol. 20, 3336–3349 (2011).

Kendall, S. L. et al. Induction of dormancy in Arabidopsis summer annuals requires parallel regulation of DOG1 and hormone metabolism by low temperature and CBF transcription factors. Plant Cell 23, 2568–2580 (2011).

Matakiadis, T. et al. The Arabidopsis abscisic acid catabolic gene CYP707A2 plays a key role in nitrate control of seed dormancy. Plant Physiol. 149, 949–960 (2009).

Preston, J. et al. Temporal expression patterns of hormone metabolism genes during imbibition of Arabidopsis thaliana seeds: a comparative study on dormant and non-dormant accessions. Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 1786–1800 (2009).

Schauser, L., Wieloch, W. & Stougaard, J. Evolution of NIN-like proteins in Arabidopsis, rice, and Lotus japonicus. J. Mol. Evol. 60, 229–237 (2005).

Zhao, M. G., Chen, L., Zhang, L. L. & Zhang, W. H. Nitric reductase-dependent nitric oxide production is involved in cold acclimation and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 151, 755–767 (2009).

Wilkinson, J. Q. & Crawford, N. M. Identification and characterization of a chlorate-resistant mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana with mutations in both nitrate reductase structural genes NIA1 and NIA2. Mol. Gen. Genet. 239, 289–297 (1993).

Seo, M. et al. Regulation of hormone metabolism in Arabidopsis seeds: phytochrome regulation of abscisic acid metabolism and abscisic acid regulation of gibberellin metabolism. Plant J. 48, 354–366 (2006).

Toh, S. et al. High temperature-induced abscisic acid biosynthesis and its role in the inhibition of gibberellin action in Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Physiol. 146, 1368–1385 (2008).

Kimura, M. & Nambara, E. Stored and neosynthesized mRNA in Arabidopsis seeds: effects of cycloheximide and controlled deterioration treatment on the resumption of transcription during imbibition. Plant Mol. Biol. 73, 119–129 (2010).

Oh, E. et al. Genome-wide analysis of genes targeted by PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR 3-LIKE5 during seed germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21, 403–419 (2009).

Oh, E. et al. PIL5, a phytochrome-interacting bHLH protein, regulates gibberellin responsiveness by binding directly to the GAI and RGA promoters in Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Cell 19, 1192–1208 (2007).

Coruzzi, G. M. & Zhou, L. Carbon and nitrogen sensing and signaling in plants: emerging ‘matrix effects’. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 4, 247–253 (2001).

Nambara, E., Kawaide, H., Kamiya, Y. & Naito, S. Characterization of an Arabidopsis thaliana mutant that has a defect in ABA accumulation: ABA-dependent and ABA-independent accumulation of free amino acids during dehydration. Plant Cell Physiol. 39, 853–858 (1998).

Nakagawa, T. et al. Improved gateway binary vectors: high-performance vectors for creation of fusion constructs in transgenic analysis of plants. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71, 2095–2100 (2007).

Mitsuhara, I. et al. Efficient promoter cassettes for enhanced expression of foreign genes in dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 37, 49–59 (1996).

Curtis, M. D. & Grossniklaus, U. A gateway cloning vector set for high-throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Physiol. 133, 462–469 (2003).

Zuo, J., Niu, Q. W. & Chua, N. H. Technical advance: an estrogen receptor-based transactivator XVE mediates highly inducible gene expression in transgenic plants. Plant J. 24, 265–273 (2000).

Earley, K. W. et al. Gateway-compatible vectors for plant functional genomics and proteomics. Plant J. 45, 616–629 (2006).

Yoo, S. D., Cho, Y. H. & Sheen, J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1565–1572 (2007).

Onate-Sanchez, L. & Vicente-Carbajosa, J. DNA-free RNA isolation protocols for Arabidopsis thaliana, including seeds and siliques. BMC Res. Notes 1, 93 (2008).

Czechowski, T., Stitt, M., Altmann, T., Udvardi, M. K. & Scheible, W. R. Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 139, 5–17 (2005).

Dekkers, B. J. W. et al. Identification of reference genes for RT-qPCR expression analysis in Arabidopsis and tomato seeds. Plant Cell Physiol. 53, 28–37 (2012).

Vandesompele, J. et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 3, RESEARCH0034 (2002).

Saleh, A., Alvarez-Venegas, R. & Avramova, Z. An efficient chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) protocol for studying histone modifications in Arabidopsis plants. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1018–1025 (2008).

Li, Y., Huang, Y., Bergelson, J., Nordborg, M. & Borevitz, J. O. Association mapping of local climate-sensitive quantitative trait loci in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 21199–21204 (2010).

Atwell, S. et al. Genome-wide association study of 107 phenotypes in Arabidopsis thaliana inbred lines. Nature 465, 627–631 (2010).

Ilic, K., Berleth, T. & Provart, N. J. BlastDigester--a web-based program for efficient CAPS marker design. Trends Genet. 20, 280–283 (2004).

Wang, L., Feng, Z., Wang, X., Wang, X. & Zhang, X. DEGseq: an R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics 26, 136–138 (2010).

Provart, N. & Zhu, T. A browser-based functional classification SuperViewer for Arabidopsis genomics. Curr. Comput. Mol. Biol. 2003, 271–272 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center and Institut Jean-Pierre Bourgin at INRA Centre de Versailles-Grignon for providing T-DNA insertion lines, Professor Yi-Fang Tsay (Academia Sinica, Taipei) for providing chl1-5, T101D/chl1-5, T101A/chl1-5 lines, and Professor Pierdomenico Perata (Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa) for providing prt6 and ate1ate2 mutants, and Professor Tsuyoshi Nakagawa (Shimane University, Japan) for providing pGWB505 and pGWB535. We thank Ayako Nambara for technical assistance in measuring ABA content, and Lisza Duermeyer for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by NSERC Discovery Grant to E.N. (RGPIN 355784 and RGPIN-2014-03621), by the JST PRESTO (11105) to M.O. and by the Labex Saclay Plant Sciences (ANR-10-LABX-0040-SPS) to A.K.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Y., S.J.R., and E.N. designed research; D.Y., V.E., V.C., M.O., M.I., M.K., A.E., Y.-M.B. and A.K. performed research; M.O., R.Y., A.P. and N.P. contributed new materials/analytical tools; Y.G. and D.G. analysed data; D.Y. and E.N. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1 - 13 (PDF 1013 kb)

Supplementary Data 1

RNA-seq expression data for Col-0 and nlp8-2 seeds imbibed for 6-h in the presence of 1 mM KCl or KNO3. (XLS 4290 kb)

Supplementary Data 2

Primers used in this study. (XLSX 59 kb)

Supplementary Movie 1

Localization of NLP7-GFP in response to nitrate. Confocal imaging was performed on NLP7-GFP plants grown on 2.5 mM ammonium succinate for 7 days. Pictures was recorded every 3 seconds after addition of 3 mM nitrate. (AVI 3284 kb)

Supplementary Movie 2

Localization of NLP8-GFP in response to nitrate. Confocal imaging was performed on NLP8-GFP plants grown on 2.5 mM ammonium succinate for 7 days. Pictures was recorded every 3 seconds after addition of 3 mM nitrate. (AVI 4133 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, D., Easwaran, V., Chau, V. et al. NIN-like protein 8 is a master regulator of nitrate-promoted seed germination in Arabidopsis. Nat Commun 7, 13179 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13179

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13179

This article is cited by

-

Genome-wide identification and characterization analysis of RWP-RK family genes reveal their role in flowering time of Chrysanthemum lavandulifolium

BMC Plant Biology (2023)

-

Genome-wide systematic characterization of the NRT2 gene family and its expression profile in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) during plant growth and in response to nitrate deficiency

BMC Plant Biology (2023)

-

The evolution and expansion of RWP-RK gene family improve the heat adaptability of elephant grass (Pennisetum purpureum Schum.)

BMC Genomics (2023)

-

Genome-wide investigation of NLP gene family members in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.): evolution and expression profiles during development and stress

BMC Genomics (2023)

-

The Research Progress and Prospects of the NIGT1.2 Gene in Plants

Journal of Plant Growth Regulation (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.