Abstract

Although anti-tumor immunity is inducible by dendritic cell (DC)–based vaccines, time- and cost-consuming “customizing” processes required for ex vivo DC manipulation have hindered broader clinical applications of this concept. Epidermal Langerhans cells (LCs) migrate to draining lymph nodes and undergo maturational changes on exposure to reactive haptens. We entrapped these migratory LCs by subcutaneous implantation of ethylene–vinyl–acetate (EVA) polymer rods releasing macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-3β (to create an artificial gradient of an LC-attracting chemokine) and topical application of hapten (to trigger LC emigration from epidermis). The entrapped LCs were antigen-loaded in situ by co-implantation of the second EVA rods releasing tumor-associated antigens (TAAs). Potent cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) activities and protective immunity against tumors were induced efficiently with each of three tested TAA preparations. Thus, tumor-specific immunity is inducible by the combination of LC entrapment and in situ LC loading technologies. Our new vaccine strategy requires no ex vivo DC manipulation and thus may provide time and cost savings.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Banchereau, J. & Steinman, R.M. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392, 245–252 (1998).

Banchereau, J. et al. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18, 767–811 (2000).

Fong, L. & Engleman, E.G. Dendritic cells in cancer immunotherapy. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18, 245–273 (2000).

Dallal, R.M. & Lotze, M.T. The dendritic cell and human cancer vaccines. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12, 583–588 (2000).

Caux, C., Dezutter-Dambuyant, C., Schmitt, D. & Banchereau, J. GM-CSF and TNF-α cooperate in the generation of dendritic Langerhans cells. Nature 360, 258–261 (1992).

Sallusto, F. & Lanzavecchia, A. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J. Exp. Med. 179, 1109–1118 (1994).

Grabbe, S. et al. Tumor antigen presentation by murine epidermal cells. J. Immunol. 146, 3656–3661 (1991).

Paglia, P., Chiodoni, C., Rodolfo, M. & Colombo, M.P. Murine dendritic cells loaded in vitro with soluble protein prime cytotoxic T lymphocytes against tumor antigen in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 183, 317–322 (1996).

Mayordomo, J.I. et al. Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells pulsed with synthetic tumour peptides elicit protective and therapeutic antitumour immunity. Nat. Med. 1, 1297–1302 (1995).

Celluzzi, C.M., Mayordomo, J.I., Storkus, W.J., Lotze, M.T. & Falo, L.D., Jr., Peptide- pulsed dendritic cells induce antigen-specific, CTL-mediated protective tumor immunity. J. Exp. Med. 183, 283–287 (1996).

Berard, F. et al. Cross-priming of naive CD8 T cells against melanoma antigens using dendritic cells loaded with killed allogeneic melanoma cells. J. Exp. Med. 192, 1535–1544 (2000).

Jenne, L., Arrighi, J.F., Jonuleit, H., Saurat, J.H. & Hauser, C. Dendritic cells containing apoptotic melanoma cells prime human CD8+ T cells for efficient tumor cell lysis. Cancer Res. 60, 4446–4452 (2000).

Russo, V. et al. Dendritic cells acquire the MAGE-3 human tumor antigen from apoptotic cells and induce a class I-restricted T cell response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 2185–2190 (2000).

Albert, M.L. et al. Immature dendritic cells phagocytose apoptotic cells via αvβ5 and CD36, and cross-present antigens to cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 188, 1359–1368 (1998).

Song, W. et al. Dendritic cells genetically modified with an adenovirus vector encoding the cDNA for a model antigen induce protective and therapeutic antitumor immunity. J. Exp. Med. 186, 1247–1256 (1997).

Specht, J.M. et al. Dendritic cells retrovirally transduced with a model antigen gene are therapeutically effective against established pulmonary metastases. J. Exp. Med. 186, 1213–1221 (1997).

Boczkowski, D., Nair, S.K., Snyder, D. & Gilboa, E. Dendritic cells pulsed with RNA are potent antigen-presenting cells in vitro and in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 184, 465–472 (1996).

Gong, J., Chen, D., Kashiwaba, M. & Kufe, D. Induction of antitumor activity by immunization with fusions of dendritic and carcinoma cells. Nat. Med. 3, 558–561 (1997).

Nair, S.K. et al. Induction of cytotoxic T cell responses and tumor immunity against unrelated tumors using telomerase reverse transcriptase RNA transfected dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 6, 1011–1017 (2000).

Hsu, F.J. et al. Vaccination of patients with B-cell lymphoma using autologous antigen-pulsed dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 2, 52–58 (1996).

Nestle, F.O. et al. Vaccination of melanoma patients with peptide- or tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 4, 328–332 (1998).

Kugler, A. et al. Regression of human metastatic renal cell carcinoma after vaccination with tumor cell–dendritic cell hybrids. Nat. Med. 6, 332–336 (2000).

Lodge, P.A., Jones, L.A., Bader, R.A., Murphy, G.P. & Salgaller, M.L. Dendritic cell–based immunotherapy of prostate cancer: immune monitoring of a phase II clinical trial. Cancer Res. 60, 829–833 (2000).

Thurner, B. et al. Vaccination with Mage-3A1 peptide-pulsed mature, monocyte-derived dendritic cells expands specific cytotoxic T cells and induces regression of some metastases in advanced stage IV melanoma. J. Exp. Med. 190, 1669–1678 (1999).

Cyster, J.G. Chemokines and the homing of dendritic cells to the T cell areas of lymphoid organs. J. Exp. Med. 189, 447–450 (1999).

Sallusto, F., Mackay, C.R. & Lanzavecchia, A. The role of chemokine receptors in primary, effector, and memory immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18, 593–620 (2000).

Dieu, M.-C. et al. Selective recruitment of immature and mature dendritic cells by distinct chemokines expressed in different anatomic sties. J. Exp. Med. 188, 373–386 (1998).

Sozzani, S. et al. Differential regulation of chemokine receptors during dendritic cell maturation: a model for their trafficking properties. J. Immunol. 161, 1083–1086 (1998).

Yanagihara, S., Komura, E., Nagafune, J., Watari, H. & Yamaguchi, Y. EBI1/CCR7 is a new member of dendritic cell chemokine receptor that is upregulated upon maturation. J. Immunol. 161, 3096–3102 (1998).

Saeki, H., Moore, A.M., Brown, M.J. & Hwang, S.T. Secondary lymphoid-tissue chemokine (SLC) and CC chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7) participate in the emigration pathway of mature dendritic cells from the skin to regional lymph nodes. J. Immunol. 162, 2472–2475 (1999).

Thomas, W.R., Edwards, A.J., Watkins, M.C. & Asherson, G.L. Distribution of immunogenic cells after painting with the contact sensitizers fluorescein isothiocyanate and oxazolone. Different sensitizers form immunogenic complexes with different cell populations. Immunology 39, 21–27 (1980).

Love-Schimenti, C.D. & Kripke, M.L. Dendritic epidermal T cells inhibit T cell proliferation and may induce tolerance by cytotoxicity. J. Immunol. 153, 3450–3456 (1994).

Porgador, A., Snyder, D. & Gilboa, E. Induction of antitumor immunity using bone marrow–generated dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 156, 2918–2926 (1996).

Mandelbolm, O. et al. CTL induction by a tumour-associated antigen octapeptide derived from a murine lung carcinoma. Nature 369, 67–71 (1994).

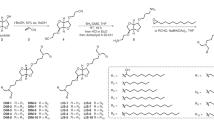

Sasaki, S. et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type-1-specific immune responses induced by DNA vaccination are greatly enhanced by mannan-coated diC14-amidine. Eur. J. Immunol. 27, 3121–3129 (1997).

Syrengelas, A.D., Chen, T.T. & Levy, R. DNA immunization induces protective immunity against B-cell lymphoma. Nat. Med. 2, 1038–1041 (1996).

Biragyn, A., Tani, K., Grimm, M.C., Weeks, S. & Kwak, L.W. Genetic fusion of chemokines to a self tumor antigen induces protective, T-cell dependent antitumor immunity. Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 253–258 (1999).

Lotze, M.T., Farhood, H., Wilson, C.C. & Storkus, W.J. Dendritic cell therapy of cancer and HIV infection. Dendritic cells: biology and clinical applications. (eds Lotze, M.T. & Thomson, A.W.) 459–485 (Academic Press, San Diego, CA; 1999).

Fushimi, T., Kojima, A., Moore, M.A. & Crystal, R.G. Macrophage inflammatory protein 3α transgene attracts dendritic cells to established murine tumors and suppresses tumor growth. J. Clin. Invest. 105, 1383–1393 (2000).

Charbonnier, A.S. et al. Macrophage inflammatory protein 3α is involved in the constitutive trafficking of epidermal Langerhans cells. J. Exp. Med. 190, 1755–1768 (1999).

Dieu-Nosjean, M.C. et al. Macrophage inflammatory protein 3α is expressed at inflamed epithelial surfaces and is the most potent chemokine known in attracting Langerhans cell precursors. J. Exp. Med. 192, 705–718 (2000).

Zitvogel, L. et al. IL-12-engineered dendritic cells serve as effective tumor vaccine adjuvants in vivo. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 795, 284–293 (1996).

Klein, C., Bueler, H. & Mulligan, R.C. Comparative analysis of genetically modified dendritic cells and tumor cells as therapeutic cancer vaccines. J. Exp. Med. 191, 1699–1708 (2000).

Matsue, H. et al. Induction of antigen-specific immunosuppression by CD95L cDNA-transfected “killer” dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 5, 930–937 (1999).

Takayama, T., Morelli, A.E., Robbins, P.D., Tahara, H. & Thomson, A.W. Feasibility of CTLA4Ig gene delivery and expression in vivo using retrovirally transduced myeloid dendritic cells that induce alloantigen-specific T cell anergy in vitro. Gene Ther. 7, 1265–1273 (2000).

Matsue, H. et al. Dendritic cells undergo rapid apoptosis in vitro during antigen-specific interaction with CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 162, 5287–5298 (1999).

Inaba, K. et al. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J. Exp. Med. 176, 1693–1702 (1992).

Kim, H.D. & Valentini, R.F. Human osteoblast response in vitro to platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta delivered from controlled-release polymer rods. Biomaterials 18, 1175–1184 (1997).

Edelman, E.R., Mathiowitz, E., Langer, R. & Klagsbrun, M. Controlled and modulated release of basic fibroblast growth factor. Biomaterials 12, 619–626 (1991).

Mohamadzadeh, M., Poltorak, A.N., Bergstresser, P.R., Beutler, B. & Takashima, A. Dendritic cells produce macrophage inflammatory protein-1γ, a new member of the CC chemokine family. J. Immunol. 156, 3102–3106 (1996).

Mummert, M.E., Mohamadzadeh, M., Mummert, D.I., Mizumoto, N. & Takashima, A. Development of a peptide inhibitor or hyaluronan-mediated leukocyte trafficking. J. Exp. Med. 192, 769–779 (2000).

Kaminski, M.J., Cruz, P.D., Jr., Bergstresser, P.R. & Takashima, A. Killing of skin-derived tumor cells by mouse dendritic epidermal T cells. Cancer Res. 53, 4014–4019 (1993).

Acknowledgements

We thank E. Gilboa for providing the E.G7-OVA and EL4 lines, and R. Granstein and J. Forman for providing the S1509a and 3LL tumor lines, respectively; P. Bergstresser and M. Mummert for thoughtful comments, D. Edelbaum and L. Ellinger for technical assistance, and P. Adcock for secretarial assistance. This study was supported by NIH grants (RO1-AR35068, RO1-AR43777, and RO1-AI43262) and by Centre de Recherches et d'Investigations Epidermiques et Sensorielles (CE.R.I.E.S.) Award (A.T.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kumamoto, T., Huang, E., Paek, H. et al. Induction of tumor-specific protective immunity by in situ Langerhans cell vaccine. Nat Biotechnol 20, 64–69 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt0102-64

Revised:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt0102-64

This article is cited by

-

Biomaterial-based platforms for in situ dendritic cell programming and their use in antitumor immunotherapy

Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer (2019)

-

Mechanistic and therapeutic overview of glycosaminoglycans: the unsung heroes of biomolecular signaling

Glycoconjugate Journal (2016)

-

Langerhans cells and dendritic cells are cytotoxic towards HPV16 E6 and E7 expressing target cells

Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy (2008)

-

Mannan-modified adenovirus as a vaccine to induce antitumor immunity

Gene Therapy (2007)

-

Behavioral Responses of Epidermal Langerhans Cells In Situ to Local Pathological Stimuli

Journal of Investigative Dermatology (2006)