Abstract

Donor T cells directed at hematopoietic system-specific minor histocompatibility antigens (mHags) are considered important cellular tools to induce therapeutic graft-versus-tumor (GvT) effects with low risk of graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. To enable the clinical evaluation of the concept of mHag-based immunotherapy and subsequent broad implementation, the identification of more hematopoietic mHags with broad applicability is imperative. Here we describe novel mHag UTA2-1 with ideal characteristics for this purpose. We identified this antigen using genome-wide zygosity-genotype correlation analysis of a mHag-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) clone derived from a multiple myeloma patient who achieved a long-lasting complete remission after donor lymphocyte infusion from an human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched sibling. UTA2-1 is a polymorphic peptide presented by the common HLA molecule HLA-A*02:01, which is encoded by the bi-allelic hematopoietic-specific gene C12orf35. Tetramer analyses demonstrated an expansion of UTA2-1-directed T cells in patient blood samples after several donor T-cell infusions that mediated clinical GvT responses. More importantly, UTA2-1-specific CTL effectively lysed mHag+ hematopoietic cells, including patient myeloma cells, without affecting non-hematopoietic cells. Thus, with the capacity to induce relevant immunotherapeutic CTLs, it’s HLA-A*02 restriction and equally balanced phenotype frequency, UTA2-1 is a highly valuable mHag to facilitate clinical application of mHag-based immunotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT) is an established and potentially curative immunotherapeutic approach for several hematological malignancies.1, 2, 3, 4 T cells present in the graft can evoke a graft-versus-tumor (GvT) reaction but, on the other hand, also cause the detrimental graft-versus-host-disease (GvHD). Relapse, persisting residual disease or incomplete donor chimerism after transplantation can be treated with donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) to enhance the GvT effect. Reversely, T-cell-depleted SCT lowers the risk of GvHD, yet promotes relapse incidence. This illustrates the fine balance between relapse of disease, GvT and GvHD after stem cell grafting.1, 5, 6, 7

In a human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched transplantation setting, both GvT and GvHD are principally elicited by T-cell responses directed at minor histocompatibility antigens (mHags) of the recipient that are not present on donor cells. The mHags are polymorphic peptides presented on the cell surface by HLA molecules. These peptides are encoded by allelic genes that can differ between patient and donor due to single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).3, 4, 8 Although several mHags are ubiquitously expressed, a specific set of mHags is derived from genes that are only expressed in benign and malignant hematopoietic cells. These hematopoietic mHags are ideal target antigens for adoptive immunotherapy after allo-SCT as they maximize the GvT effect without causing GvHD.3, 8, 9

Even though hematopoietic restriction is of vital importance, the immunotherapeutic relevance of a mHag is not solely dependent on its hematopoietic-specific tissue distribution. For broad application in immunotherapy, a mHag must also display an equally balanced phenotype frequency, be presented by a common HLA molecule and have strong immunogenic potential.8, 10 Currently, only a limited number of completely characterized hematopoietic mHags fulfil these criteria.

Recently, we developed a powerful and rapid genetic approach for the identification of new therapeutic mHags.9 This genome-wide zygosity-genotype correlation analysis is a convenient method to precisely map the genomic locus of mHags and identify the mHag epitopes. To identify the most relevant mHags, we isolated mHag-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) clones from SCT-recipients with at least one of the HLA molecules -A*01, -A*02, -A*03, -A*11 or -A*24, as >92.5% of the Caucasian population express one or more of these alleles. Then we selected CTL recognizing a mHag with a phenotype frequency of 10–85% for further analysis, to achieve a considerable chance of mHag-mismatching.9, 10 Using this strategy, we now identified the new mHag UTA2-1 with characteristics fulfilling all the criteria for a relevant immunotherapeutic mHag. With the equally balanced phenotype frequency, HLA-A*02:01 restriction, hematopoietic tissue distribution and relevant immunogenic expression on malignant cells, UTA2-1 is one of the few ideal mHags that can substantially facilitate the implementation of clinical trials for a timely evaluation of mHag-based treatment strategies in patients with hematological malignancies.

Material and methods

Patient history

A 52-year-old male patient, diagnosed with multiple myeloma (MM), received initial induction therapy consisting of Vincristine, Adriamycin and Dexamethason, followed by intermediate dose Melphalan, leading to a partial response. Then he received a full graft stem cell transplant from his HLA-identical brother after conditioning with cyclophosphamide and total body irradiation. This treatment resulted in acute grade I GvHD of the skin, accompanied by a very good partial response that lasted for 2 years. The subsequent relapse was treated with Thalidomide, Adriamycin and Dexamethason followed by a DLI (1 × 107 T cells/kg) from the original donor. As the patient did not benefit from this treatment nor from a subsequent experimental therapy consisting of Vincristine, Adriamycin and Dexamethason in combination with Oblimersen sodium (Genasense, anti-Bcl-2), he received a second, higher dose DLI (5 × 107 T cells/kg). This second DLI induced a strong GvT response, resulting in complete remission (CR), which persisted for over 8 years.

Cells

Blood samples from both recipient and donor were collected at various time points, after written informed consent in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by Ficoll-Paque density centrifugation and cryopreserved.

EBV-transformed B cells (EBV-LCL) from recipient and donor and from individuals from a Caucasian population in the HapMap database (CEU) were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Integro, Zaandam, the Netherlands) and standard antibiotics (1% penicillin/streptomycin).

MM cell lines U266, L363 and UM9 were also cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and antibiotics.

Primary MM cells from the recipient’s bone marrow (BM) were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and 5 ng/ml IL-6 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

Primary chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells were thawed in IMDM (Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Media; Invitrogen) with 10% FBS and kept in culture overnight in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS.

Phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated T-cell blasts (PHA-blasts) were generated by stimulating PBMC with PHA (1 μg/ml) in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% pooled human serum (Sanquin, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) plus antibiotics and expanded by adding IL-2 (120 IU/ml).

Recipient stromal cells were cultured from a pre allo-SCT BM sample in DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium) with 10% FBS supplemented with antibiotics and IL-6 (5 ng/ml). Recipient fibroblasts (FB) that were derived from a skin biopsy sample were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and antibiotics; keratinocytes (KC) were cultured in KGM-2 medium (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland).

T-cell cloning

From PBMC, HLA-DR+ T cells were isolated by magnetic-activated cell sorting after depletion of CD14+ and CD19+ cells following the instructions of the manufacturer (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). These cells were then cloned by limiting dilution at 0.3 cell/well and stimulated with a feeder cell-cytokine mixture. Culture medium was RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% human serum and antibiotics. Growing cells were expanded using the same feeder cell-cytokine mixture and cryopreserved until use.

Peptides

Commercially synthesized and >85% purified 9-mer peptides (Genscript, Piscataway, NJ, USA) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at a concentration of 20 mg/ml and then diluted in phosphate-buffered saline for use in functional assays.

Tetrameric HLA/peptide complexes (tetramers)

A phycoerythrin-labelled tetramer for the mHag peptide QLLNSVLTL was produced as described elsewhere.11 Briefly, HLA-A*02:01 heavy chain, β2-microglobulin and mHag peptide were refolded. Monomeric complexes were concentrated, biotinylated, HPLC (high-pressure liquid chromatography) purified and bound to streptavidin-phycoerythrin (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). The tetramers were HPLC purified and preserved at −20 °C after addition of 16% glycerol and 0.5% bovine serum albumin.

Immunophenotyping

Cells labelled with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA and Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) were analyzed with a FACS (fluorescence-activated cell sorting) Calibur flow cytometer (BD). Acquired data were analyzed with CellQuest software (BD).

Chromium release cytotoxicity assays

Standard 51Cr release-based cytotoxicity assays were executed as previously described.12 In short, effector T cells were incubated with 51Cr-labelled target cells (100 μCi per 106 cells) at 37 °C for 4 hours, at indicated effector:target ratios. Spontaneous and maximal 51Cr-releases were determined by incubating target cells with medium alone and with 0.1% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline, respectively. The 51Cr content of the cell-free supernatants was measured using a Microbeta-2 reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The percentage of specific lysis was calculated by using the following formula: Percentage of specific lysis=100% × (experimental 51Cr release−spontaneous 51Cr release)/(maximum 51Cr release−spontaneous 51Cr release).

Bioluminescence-based cytotoxicity assays

Effector T cells were incubated for 24 h with luciferase-transduced MM cell lines in white opaque flat-bottomed 96-well plates (Corning Inc./Costar, Corning, NY, USA). After addition of 125 μg/ml beetle luciferin, the light signal emitted from surviving MM cells was determined using a luminometer (SpectraMax, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The percentage of lysis of MM cells was calculated by using the following formula: Percentage of specific lysis=100% × 1−(mean of triplet experimental luciferase signal/mean of triplet background luciferase signal).13

FACS-based cytotoxicity assays

Lysis of primary MM cells was determined by previously described FACS-based cytotoxicity assays.14 In short, the target MM cells were incubated with the effector T cells for 18 h. CD38+CD138+Topro− surviving MM cells were then counted by flowcytometry. The percentage of lysis was calculated by using the following formula: Percentage of lysis=100% × 1−(absolute counts of CD38+CD138+Topro− cells/absolute counts of CD38+CD138+Topro− cells in control wells).

For CLL cells, a modified protocol was used: CLL cells were stained with Far Red DDAO-SE (Invitrogen) and incubated with effector T cells for 18 h. Surviving CLL cells were measured as DDAO+DIOC-6+PI− cells and the percentage of lysis was calculated using the following formula: Percentage of specific lysis=100% × (Percentage of apoptosis−percentage of apoptosis in control wells/percentage of viable cells in control wells).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The interferon gamma (IFN-γ) content of cell-free supernatants was determined using a commercial ELISA kit (Pelipair, Sanquin, Active Bioscience GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Genome-wide zygosity-genotype correlation analysis

The correlation of experimental data with HapMap SNP genotypes was performed and analyzed as previously described.9, 10 In short, the mHag phenotypes (mHag+ or mHag−) of HLA-A*02:01+ CEPH individuals from HapMap trios (father–mother–child) were determined, subsequently mHag zygosities (+/+, +/− or −/−) of the CEPH individuals in the father–mother–child trios were deduced. Release No.24 HapMap SNP genotypes was downloaded from the HapMap website (www.hapmap.org) for the correlation analysis.

Microarray gene expression analysis

Malignant cells were isolated from PBMC and BM samples from patients with CML (chronic myeloid leukemia), AML (acute myeloid leukemia), ALL (acute lymphoid leukemia), CLL and MM by flow cytometry based on expression of CD34, CD33, CD19, CD19/CD5 and CD38/CD138, respectively. Non-malignant B cells, T cells, monocytes and hematopoietic stem cells were isolated from PBMC or BM based on expression of CD19, CD3, CD14 and CD34, respectively. Non-hematopoietic cells included skin-derived FB and KC and proximal tubular epithelial cells (kindly provided by Dr C. van Kooten, Department of Nephrology, University Medical Center, Leiden) cultured with and without IFN-γ (100 IU/ml). Total RNA was isolated using small- and micro-scale RNAqueous isolation kits (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA), and amplified using the TotalPrep RNA amplification kit (Ambion). After preparation using the whole-genome gene expression direct hybridization assay (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), cRNA samples were dispensed onto Human HT-12 v3 Expression BeadChips (Illumina). Hybridization was performed in the Illumina hybridization oven for 17 h at 58 °C. Microarray gene expression data were analyzed using Rosetta Resolver 7.2 software (CMSB-NBIC, Leiden, The Netherlands).

Real-time PCR

RNA was extracted using Trizol; cDNA synthesis was performed using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit for real-time PCR with AMV transcriptase (Roche). For the reaction mixture, a SYBR green PCR core reagent kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used, with 5 μM of each primer and 100 ng of the cDNA sample. For the target gene C12orf35, the PCR primers were (f) 5′-tgctggagtttaaattatgtc-3′ and (r) 5′-cgagagtcttgaattaacatt-3′, CD45 primers (f) 5′-gcctcccagggaccgtaat-3′ and (r) 5′-gatagtctccattgtgaaaataggcct-3′ were used to control for hematopoietic cell contamination and primers for the housekeeping gene GUS were (f) 5′-gaaaatatgtggttggagagctcatt-3′ and (r) 5′-ccgagtgaagatccccttttta-3′. PCR amplification and quantification were performed using the ViiA7 detection system (Applied Biosystems). All cDNA samples with a Ct>35 for GUS were excluded. The expression of the candidate gene was calculated with the following formula: relative quantity C12orf35=2−(ΔCt sample−ΔCt calibrator sample), using PBMC from a healthy donor for calibration.

PCR typing UTA2-1 and other mHags

To confirm the mHag genotype of recipient and donor and to type other individuals for UTA2-1, PCR primers were (f1) 5′-cgtatggttgaactcaccaatg-3′ or (f2) 5′-cgtatggttgaactcaccaatgag-3′ and (r) 5′-ccacagaagatctaatgggactg-3′.

For the other available mHags, we used previously described methods of typing.15, 16

Results

CTL 503A1 recognizes an HLA-A*02:01-restricted mHag

To identify new mHags with immunotherapeutic relevance, we selected an HLA-A*02+ MM patient who had a robust GvT effect after DLI, leading to a long-lasting CR. In this patient–donor combination, there were no mismatches for other known mHags (Supplementary Table S1). Direct limiting dilution of HLA-DR+ T cells, from cryopreserved PBMC obtained at the peak of this response, as measured by a fast decline in M-protein levels 2 months after the second DLI, led to the generation of nine mHag-specific CD8+ CTL clones that selectively recognized recipient’s but not donor’s antigen-presenting cells.

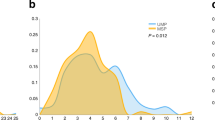

Among these, CTL 503A1 effectively recognized and killed recipient PHA-blasts, with 26% lysis after 4 hours (Figure 1a). The mHag-specific CTL clones were screened for HLA restriction and mHag phenotype frequency using a panel of EBV-LCL from CEPH individuals with different combinations of HLA molecules. We established that the mHag recognized by CTL 503A1 was presented by HLA-A*02:01 (Figure 1b) and the mHag phenotype frequency in this first test panel was estimated to fall within our predefined limits of 10–85%, whereas none of the other CTL clones met our selection criteria (Supplementary Table S2). Therefore, CTL 503A1 was selected for further analysis to reveal its target mHag.

T-cell clone 503A1 selectively recognizes an HLA-A*02-restricted mHag, which is encoded by a non-synonymous coding SNP on chromosome 12. (a) Cytotoxic T-cell clone 503A1 lyses antigen-presenting cells (APC) from the SCT recipient but not from the donor in a conventional chromium release assay (left graph). PHA-blasts of both recipient and donor are used as APC. Clone 503A1 also produces a greater amount of IFN-γ when in contact with recipient APC in comparison to donor APC (right graph).(b) In a panel of EBV-LCLs only those cells that are at least HLA-A*02 positive are recognized by CTL 503A1. Five out of six random selected HLA-A*02 positive EBV-LCL test positive in this IFN-γ ELISA experiment. (c) Genome-wide zygosity-genotype correlation analysis using the zygosities of 30 CEPH-individuals led to 15 100% correlating SNPs located on chromosomes 3, 4, 10, 12 and 14. After correlating them with the mHag+ CEPH-individuals with undeducible zygosities, six SNPs on chromosome 12 were still in 100% correlation with the experimental data. Of these, only SNP rs2166807 leads to the transcription of a peptide. (d) SNP rs2166807 (bold box) is located on gene C12orf35 on chromosome 12, together with several other SNPs. The letters in the boxes represent the alterations in amino acids caused by the polymorphisms in this region. Also, frameshift (fs) SNPs are depicted.

Genome-wide zygosity-genotype correlation analysis points out SNP rs2166807 on gene C12orf35

To perform the genome-wide zygosity-genotype correlation analysis, we determined the mHag phenotypes of 38 HLA-A*02:01+ CEPH individuals from 16 different father–mother–child trios, by testing the IFN-γ response of CTL 503A1 against their EBV-LCL. In this panel, 9/24 unrelated persons (fathers and mothers of trios only) were mHag+, leading to an estimated phenotype frequency of 37.5% (Supplementary Table S3).

From the phenotypic data, we could deduce the mHag zygosities of 30 CEPH individuals, using the Mendelian segregation pattern of the father–mother–child trios. The 30 deduced zygosities were correlated to around 4 million SNPs from the whole genome using the mHag-identification-modified software ssSNPer (Queensland Institute of Medical Research, Brisbane, QL, Australia). This analysis revealed 15 SNPs with 100% correlation with the mHag zygosities of the CEPH individuals scattered over several chromosomes (Figure 1c). After manual comparison of the genotypes of these SNPs to the eight mHag+ phenotypes with undeducible zygosities (which were thus not included in the primary analysis), only six 100% correlating SNPs remained. These six SNPs were located together on chromosome 12 in the region of uncharacterized gene C12orf35. Only one of them, rs2166807, was a non-synonymous coding SNP that causes a proline (P) to leucine (L) substitution in the transcribed peptide (Figure 1d). Furthermore, the original SCT-recipient carried the leucine-encoding allele for rs2166807, while the donor was homozygous for rs2166807P. This fitted the possibility that rs2166807L encoded the mHag recognized by CTL 503A1. We therefore proceeded with this candidate SNP.

mHag UTA2-1 is encoded by rs2166807L and has peptide sequence QLLNSVLTL

To test if the rs2166807L allele indeed encoded the mHag recognized by CTL clone 503A1, we analyzed all nonameric peptides containing the substituted leucine at one amino acid shifting positions for recognition by this T-cell clone. Only sequence QLLNSVLTL, with the third amino acid being the variable leucine, was recognized by CTL 503A1 (Figure 2a). None of the other shifting peptides or the allelic counterpart (QLPNSVLTL) caused any activation of the clone (Figure 2b), confirming that QLLNSVLTL was the sought mHag epitope. We designated this novel mHag UTA2-1.

The optimal peptide sequence of mHag UTA2-1 is 9-mer QLLNSVLTL. (a) A mHag− EBV-LCL was loaded with 9-mer peptides holding the substituted leucine in a concentration of 10 μM and tested for recognition by CTL 503A1 with IFN-γ ELISA. Only peptide sequence QLLNSVLTL was recognized and consequently identified as mHag UTA2-1. As a positive control, mHag+ EBV-LCL was used. (b) Similarly, mHag UTA2-1 (QLLNSVLTL) and the allelic peptide (QLPNSVLTL) were exogenously loaded on the mHag− EBV-LCL in various concentrations and tested for recognition by 503A1 with IFN-γ ELISA.

Hematopoietic cell-specific tissue distribution of mHag UTA2-1

After determining the genetic locus and peptide sequence, we further explored several characteristics of mHag UTA2-1 to assess its immunotherapeutic potential. To this end, we first collected data on the tissue distribution of gene C12orf35 from gene portal www.biogps.org17 (Supplementary Figure 1) and re-evaluated this with microarray data on a selected group of hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells (Figure 3a). Both data sets revealed an overexpression of the gene in most hematopoietic cells and low expression levels in other tissue, especially in GvHD organs like the liver, gut and skin. The microarray data, however, did show intermediate expression in one of the three IFN-γ-pretreated KC. Hence, the cell surface antigen presentation of UTA2-1 on KC had to be determined. Therefore, we tested the reactivity of clone 503A1 against KC derived from the original mHag+ SCT recipient and used patient’s skin FB and BM stromal cells as additional non-hematopoietic cells. In an IFN-γ release experiment, KC, FB or BM stromal cells from the original patient were not recognized by 503A1 (Figure 3b). Exogenous loading of these target cells with the synthetic UTA2-1 peptide did, however, activate CTL 503A1, indicating that these non-hematopoietic cells, including KC, lacked the functional expression of the mHag but expressed sufficient levels of HLA molecules to bind and present the synthetic mHag peptide as well as other co-stimulatory molecules that are necessary to activate T cells. Moreover, in a degranulation marker assay that has been shown to correlate well with cellular cyotoxicity,18 KC were not recognized by clone 503A1, irrespective of pre-incubation with tumor necrosis factor-α and IFN-γ, confirming that KC lacked the functional expression of UTA2-1, even under inflammatory conditions (Figure 3c).

UTA2-1 expression is restricted to hematopoietic tissue and CTL 503A1 can lyse various malignant hematopoietic mHag+ cells. (a) The expression level of gene C12orf35 was assessed in an established microarray, showing an overexpression of the gene in hematopoietic tissue and low expression levels in non-hematopoietic cells. Among the hematopoietic cells, expression is highest in CLL cells and PHA T-cell blasts,and lowest in hematopoietic stem cells, immature dendritic cells and CML cells. We set the cutoff for T-cell recognition on a MFI of 30 according to our findings in functional experiments using EBV-LCL and keratinocytes. (b) The non-hematopoietic cell types fibroblasts, keratinocytes and stromal cells were not recognized by CTL 503A1 in an E:T ratio of 5:1 using IFN-γ ELISA. After incubating the cells with 10 μM exogenous peptide, 503A1 did become activated. (c) The keratinocytes did not induce an increase in expression of degranulation marker CD107a on CTL 503A1 in a E:T ratio of 5:1 as measured by FACS. This was independent of pre-incubation with tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and IFN-γ (both 100 IU/ml) for 3 days. After incubating the target cells with 10 μM exogenous peptide, CD107a on the CTL was upregulated.

Cytotoxicity of UTA2-1-directed T cells against malignant cells in vitro

To assess the immunogenic capacity of UTA2-1, we performed various types of cytotoxicity experiments with malignant hematopoietic cells. These assays demonstrated that CTL 503A1 effectively lysed both cells from the MM cell line U266 carrying the UTA2-1 antigen (Figure 4a) and primary MM cells from the original patient and other mHag+ individuals (Figure 4b), whereas HLA-A*02− or mHag-negative MM cells were not lysed. Moreover, the genotypically mHag-positive but HLA-A*02− MM cell line UM9 was also killed after retroviral transduction of this line with HLA-A*02:01 (Figure 4a), demonstrating the relevant expression of mHag in several MM cells. Furthermore, CTL 503A effectively lysed several UTA2-1+ CLL cells in an HLA-restricted and dose-dependent manner, also indicating the relevant cell surface expression of UTA2-1 on primary CLL cells (Figure 4c).

Cytotoxicity in vitro and in vivo monitoring of UTA2-1-directed T-cell response with tetramer staining correlated to clinical GvT. (a) Clone 503A1 effectively kills HLA-A*02+ mHag+ MM cell line U266 in various E:T ratios after 24 h incubation in a bioluminescence cytotoxicity assay. Either mHag− (L363) or HLA-A*02− (UM9) MM cell lines are not lysed by 503A1, but after transduction of genotypically mHag+ UM9 with HLA-A*0201 this cell line is also recognized. U266 survives unhindered in the presence of an irrelevant mHag-directed T-cell clone (3AB11). (b) Also, primary MM cells from the original mHag+ SCT-recipient (pt A) were specifically lysed by 503A1 in a FACS cytotoxicity assay after incubation together for 18 h. Other primary MM cells were also killed in an antigen-specific and dose-dependent manner, although with lower efficacy than pt A. (c) Various HLA-A*0201+ mHag+ primary CLL cells were lysed in a dose-dependent manner by CTL 503A1 likewise in a FACS cytotoxicity assay, whereas HLA-A*0201− mHag− CLL cells were not (left graph). Moreover, we measured IFN-γ responses of 503A1 to some of the CLL samples (right graph). (d) Gene C12orf35 is highly expressed on both benign and malignant hematopoietic cells. All values are relative to a calibrator PBMC sample and C12orf35 gene expression is normalized to the housekeeping gene GUS. Median values are depicted. (e) The time course from diagnosis of MM until present is depicted, with the solid line representing the course of the disease, measured by M-protein level in the peripheral blood (left y axis). The dotted line indicates the percentage of CD8+ T cells that stained positive with the UTA2-1 tetramer (right y axis). After the SCT and after both DLIs the relative amount of tetramer-positive T cells increased, which coincided with clinical responses leading to long-lasting responses after the SCT and after the second DLI. After the SCT and the first DLI also short episodes of mild GvHD of the skin occurred, for which the patient was treated with topical steroids.

Subsequently, we evaluated the expression levels of the C12orf35 gene in various benign and malignant hematopoietic cell types using real-time quantitative PCR (Figure 4d). All tested cells expressed moderate-to-high levels of the gene C12orf35. Expression levels were highest in the lymphoid cell types, especially the chronic lymphatic leukemia samples, which was in accordance with the microarray data.

Although microarray data had indicated low gene expression of C12orf35 in CML cells and part of the AML cells, real-time PCR revealed comparable levels of expression with MM cells.

Expansion of CTL 503A1 is associated with clinical response in vivo

Finally, to evaluate the correlation between T-cell responses directed at mHag UTA2-1 and the clinical GvT effects seen in the original patient, we determined the frequencies of UTA2-1-specific CTLs in the circulation of the patient using HLA-A*02/UTA2-1 tetramers. We found a significant rise in tetramer-positive T cells, soon after allo-SCT and after both DLIs. The clinical response around allo-SCT had partly started in response to induction treatment but was intensified after allo-SCT. After induction treatment given before the second DLI, a further rise in M-protein levels already went on, changing to a swift drop of M protein after DLI. Thus, GvT effects had to be involved in these clinical responses. The increase in tetramer+ cells coincided with the achievement of a very good partial response after SCT and a persistent CR after the second DLI, suggesting the involvement of UTA2-1-specific CTLs in clinical GvT responses. Nonetheless, the increase in UTA-2-specific T cells did not lead to a GvT response after the first DLI.

Discussion

After its introduction in the mid-nineties, the concept of targeting of hematopoietic tissue-restricted mHags for immunotherapy of hematological malignancies has been embraced with great enthusiasm. Nonetheless, a thorough clinical evaluation of this novel concept has not been carried out yet, because the completion of such clinical studies within a reasonable time frame requires the identification of sufficient number of mHags that can be applied in a broad range of patients.

Over the past years, several research groups have succeeded to discover new mHags. Nonetheless, a large fraction of these studies were designed either to understand the biology of mHags or to show the proof of principle of new mHag identification strategies, without always paying attention to the (broad) therapeutic applicability of the discovered mHags. For instance, several of the identified mHags are not restricted to hematopoietic tissue, and are therefore not relevant for therapeutic application. Several others are presented by rare HLA molecules or display a rather unbalanced phenotype frequency. Two decades after its identification, HA-1 is still the only hematopoietic mHag that in itself can account for application in 6-12% of patients, depending on the transplantation setting (HLA-matched sibling vs. unrelated donor transplantation).8, 19

Using our recently developed mHag identification strategy and a directed approach towards the identification of the most therapeutically relevant mHags, we now identified mHag UTA2-1. Several characteristics of this new mHag are similar to that of mHag HA-1, which is considered to be the most immunotherapeutically relevant mHag identified so far. Both functional assays and real-time PCR experiments reveal the hematopoietic-restricted tissue distribution of UTA2-1, similar to HA-1. Furthermore, according to data of large population studies from HapMap, mHag UTA2-1 has a phenotype frequency of 40.2% in Caucasian people and between 11.3% and 38.0% in all other populations included in HapMap (www.hapmap.org). With this well-balanced frequency, the likelihood of encountering a mHag+ SCT recipient with a mHag− donor is around 24% in the matched unrelated donor setting in the Caucasian population, which is almost maximal for any mHag. Moreover, UTA2-1 is just as HA-1 presented by HLA-A*02:01, which is the most common HLA molecule in Caucasians with a mean frequency of 46% (range 39–53%; www.allelefrequencies.net) in European and North American Caucasoid populations. Therefore, we conclude that 11.3% of all Caucasian patients receiving an HLA-matched allo-SCT will express this mHag and have an available HLA-matched mHag-mismatched donor. This percentage is comparable with that of HA-1 and superior to all other mHags identified thus far.

Several techniques from both forward and reverse immunology approaches have been developed to identify mHags, including peptide elution, cDNA library screening, genetic linkage analyses and recently MHC tetramer-based screening.6, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 Although the reverse immunology strategies are theoretically more suitable for the discovery of therapeutically relevant mHags, often difficulties arise when the immunogenicity of the mHag needs to be confirmed. This is actually the main reason why the most successful strategies still are the forward immunology methods, with the genome-wide genetic linkage analyses being the most successful and convenient.6, 21, 29 Although the forward identification methods do not allow a priori selection of mHag-specific CTL on HLA restriction, phenotype frequency and tissue distribution, we have captured a part of this drawback by carefully choosing recipient–donor combinations and immediately performing the HLA restriction and phenotype frequency analyses on the generated T-cell clones, before proceeding with the epitope identification. In our directed approach, which is based on the powerful, convenient and rapid genome-wide zygosity-genotype correlation analysis, we aim at significantly augmenting the identification efficacy of therapeutic mHags,by generating T-cell clones only from patients with at least one of the five most frequent HLA-A molecules, that is, HLA-A*01, -A*02, -A*03, -A*11 or -A*24 and by subsequently selecting those CTL recognizing mHag with balanced phenotype frequencies.

Beyond its drawbacks, the most significant advantage of mHag identification with forward strategies appears that the identified mHags are virtually always relevant for the clinical outcome in the patient, because the T cells directed against these mHags have been shown to correlate with clinical responses.22, 30 Indeed, we also discovered UTA2-1 in a post-SCT PBMC sample from a MM patient who after his successful DLI remained in CR for >8 years. Using tetramer staining, we demonstrated an expansion of UTA2-1-specific T cells, which coincided with the achievement of the CR after the second DLI. Furthermore, we found an evident expansion of these T cells also soon after SCT, during development of a very good partial response, suggesting the involvement of UTA2-1-specific T cells in the development of multiple GvT responses. But, perhaps more importantly, we clearly demonstrated that the isolated UTA2-1-specific CTL readily lysed not only the HLA-matched mHag+ MM cell lines but also the primary MM cells derived from the patient in an antigen-specific manner, thus indicating the functional ability of UTA2-1-specific CTLs to lyse MM cells. In our view, this information is highly important and may be even more relevant than a mere correlation analysis with tetramers to determine the true immunotherapeutic potential of mHags. In our study, we also observed an expansion of UTA2 1-specific T cells after the first DLI, after which little or no clinical response occurred, this finding actually suggests that next to the development of mHag reactivity, multiple factors contribute to, and may be necessary for, the development of a proper GvT reaction. It is conceivable that progression rate of disease, tumor load, pretreatment regimen, concurrent immunosuppressive medication and immunoregulatory mechanisms within the graft are involved. Also considering the tremendous capacity of MM cells to evade immune responses (manuscript in preparation) and as also evident from several studies in solid tumor settings,31, 32, 33 it is actually not that surprising that increases in T-cell responses are not always associated with clinical responses. Nonetheless, the question remains whether other mHag responses were involved in the development of GvT in this patient. It is highly likely that the answer is yes, because we have also isolated CTL clones from this patient that are not specific for UTA2-1. However, as we have not set out to identify these other mHags as those CTL clones did not meet our selection criteria, and as there were no other known mHag mismatches between the patient and the donor, we could not quantify and compare mHag-responses in this patient.

Although we have tested the cytotoxic potential of UTA2-1-directed T cells only against MM and CLL cells, our molecular experiments suggest that cells from several other hematological malignancies may also express this mHag in sufficient levels to benefit from UTA2-1-directed immunotherapy. However, seeing the variability in expression levels mainly in patients with myeloid malignancies, this will still require individualized testing of antigen expression before treatment.

We and the others have shown that mHag-based immunotherapy can very effectively destroy hematopoietic tumors cells in mouse models.34, 35 This supports the hypothesis that adoptive immunotherapy directed at even a single mHag can contribute to a better outcome for patients with hematological malignancies. Hence, a potential option for mHag-based immunotherapy is the adoptive transfer of mHag-specific T cells, either in their native form or after T-cell receptor transfer. The main difficulty of evaluating the clinical potential of mHag-specific therapy in an adoptive immunotherapy setting lies, however, in the logistic issues to generate CTL against several mHags within one trial. Consequently, adoptive T-cell transfer approaches have so far been limited to one or at most two defined mHags and are therefore difficult to complete within a reasonable time frame with meaningful results, especially if they are executed as single center trials. Mainly due to this reason, until now only one small clinical trial has been executed in which seven leukemia patients were infused with mHag-specific ex vivo-expanded CTL. In this study, the GvT effect seemed to be augmented, but unfortunately there was no long-term persistence of the transferred T cells in the patients, and all the patients eventually relapsed. Furthermore, there was quite some toxicity as the mHags were not selected for hematopoietic-restricted tissue distribution.35, 36

In our opinion, an alternative approach, that is, vaccination of patients with dendritic cells loaded with peptides or mRNA of mHags seems to be the most feasible strategy to assess the clinical relevancy of mHag-based immunotherapy in hematological malignancies. With this approach, many mHags can be conveniently included in the trials, and it is also possible to execute the trials in a multicenter setting, as there is ample experience with dendritic cell vaccination in several institutes. We are therefore currently starting both single and multicenter clinical trials in which DLI-unresponsive patients with MM or other hematopoietic malignancies will be treated with a second DLI in combination with dendritic cell vaccines loaded with selected hematopoietic mHags, including UTA2-1. These studies, may in the near future, reveal the true clinical value of UTA2-1 and other hematopoietic mHags as immunotherapeutic tools for the treatment of blood cancers.

In conclusion, we here describe newly identified mHag UTA2-1, which is from the point of view of immunotherapeutic applicability, a highly valuable mHag. For a definitive evaluation of mHag-based immunotherapeutic strategies, however, the execution of clinical trials is essential. The addition of broadly applicable mHag UTA2-1 to the spectrum of available mHags will significantly contribute to achieve this goal in a timely manner.

References

Kolb HJ . Graft-versus-leukemia effects of transplantation and donor lymphocytes. Blood 2008; 112: 4371–4383.

Lokhorst H, Einsele H, Vesole D, Bruno B, San Miguel J, Perez-Simon JA et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus statement regarding the current status of allogeneic stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 4521–4530.

Akatsuka Y, Morishima Y, Kuzushima K, Kodera Y, Takahashi T . Minor histocompatibility antigens as targets for immunotherapy using allogeneic immune reactions. Cancer Sci 2007; 98: 1139–1146.

Goulmy E . Human minor histocompatibility antigens: new concepts for marrow transplantation and adoptive immunotherapy. Immunol Rev 1997; 157: 125–140.

Ringden O, Karlsson H, Olsson R, Omazic B, Uhlin M . The allogeneic graft-versus-cancer effect. Br J Haematol 2009; 147: 614–633.

van Bergen CA, Rutten CE, van der Meijden ED, van Luxemburg-Heijs SA, Lurvink EG, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ et al. High-throughput characterization of 10 new minor histocompatibility antigens by whole genome association scanning. Cancer Res 2010; 70: 9073–9083.

Mutis T, Brand R, Gallardo D, van Biezen A, Niederwieser D, Goulmy E . Graft-versus-host driven graft-versus-leukemia effect of minor histocompatibility antigen HA-1 in chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Leukemia 2010; 24: 1388–1392.

Spierings E, Goulmy E . Expanding the immunotherapeutic potential of minor histocompatibility antigens. J Clin Invest 2005; 115: 3397–3400.

Spaapen RM, Lokhorst HM, van den Oudenalder K, Otterud BE, Dolstra H, Leppert MF et al. Toward targeting B cell cancers with CD4+ CTLs: identification of a CD19-encoded minor histocompatibility antigen using a novel genome-wide analysis. J Exp Med 2008; 205: 2863–2872.

Spaapen RM, de Kort RA, van den Oudenalder K, van Elk M, Bloem AC, Lokhorst HM et al. Rapid identification of clinical relevant minor histocompatibility antigens via genome-wide zygosity-genotype correlation analysis. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 7137–7143.

Kostense S, Ogg GS, Manting EH, Gillespie G, Joling J, Vandenberghe K et al. High viral burden in the presence of major HIV-specific CD8(+) T cell expansions: evidence for impaired CTL effector function. Eur J Immunol 2001; 31: 677–686.

Spaapen R, van den Oudenalder K, Ivanov R, Bloem A, Lokhorst H, Mutis T . Rebuilding human leukocyte antigen class II-restricted minor histocompatibility antigen specificity in recall antigen-specific T cells by adoptive T cell receptor transfer: implications for adoptive immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: 4009–4015.

Brown CE, Wright CL, Naranjo A, Vishwanath RP, Chang WC, Olivares S et al. Biophotonic cytotoxicity assay for high-throughput screening of cytolytic killing. J Immunol Methods 2005; 297: 39–52.

van der Veer M, de Weers M, van Kessel B, Bakker JM, Wittebol S, Parren PW et al. Towards effective immunotherapy of myeloma: enhanced elimination of myeloma cells by combination of lenalidomide with the human CD38 monoclonal antibody daratumumab. Haematologica 2011; 96: 284–290.

Spierings E, Goulmy E . Minor histocompatibility antigen typing by DNA sequencing for clinical practice in hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Methods Mol Biol 2012; 882: 509–530.

Spierings E, Drabbels J, Hendriks M, Pool J, Spruyt-Gerritse M, Claas F et al. A uniform genomic minor histocompatibility antigen typing methodology and database designed to facilitate clinical applications. PLoS One 2006; 1: e42.

Wu C, Orozco C, Boyer J, Leglise M, Goodale J, Batalov S et al. BioGPS: an extensible and customizable portal for querying and organizing gene annotation resources. Genome Biol 2009; 10: R130.

Betts MR, Brenchley JM, Price DA, De Rosa SC, Douek DC, Roederer M et al. Sensitive and viable identification of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells by a flow cytometric assay for degranulation. J Immunol Methods 2003; 281: 65–78.

den Haan JM, Meadows LM, Wang W, Pool J, Blokland E, Bishop TL et al. The minor histocompatibility antigen HA-1: a diallelic gene with a single amino acid polymorphism. Science 1998; 279: 1054–1057.

Hombrink P, Hadrup SR, Bakker A, Kester MG, Falkenburg JH, von dem Borne PA et al. High-throughput identification of potential minor histocompatibility antigens by MHC tetramer-based screening: feasibility and limitations. PLoS One 2011; 6: e22523.

Kawase T, Nannya Y, Torikai H, Yamamoto G, Onizuka M, Morishima S et al. Identification of human minor histocompatibility antigens based on genetic association with highly parallel genotyping of pooled DNA. Blood 2008; 111: 3286–3294.

de Rijke B, van Horssen-Zoetbrood A, Beekman JM, Otterud B, Maas F, Woestenenk R et al. A frameshift polymorphism in P2X5 elicits an allogeneic cytotoxic T lymphocyte response associated with remission of chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Invest 2005; 115: 3506–3516.

Brickner AG, Evans AM, Mito JK, Xuereb SM, Feng X, Nishida T et al. The PANE1 gene encodes a novel human minor histocompatibility antigen that is selectively expressed in B-lymphoid cells and B-CLL. Blood 2006; 107: 3779–3786.

den Haan JM, Sherman NE, Blokland E, Huczko E, Koning F, Drijfhout JW et al. Identification of a graft versus host disease-associated human minor histocompatibility antigen. Science 1995; 268: 1476–1480.

Dolstra H, Fredrix H, Maas F, Coulie PG, Brasseur F, Mensink E et al. A human minor histocompatibility antigen specific for B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Exp Med 1999; 189: 301–308.

Ivanov R, Aarts T, Hol S, Doornenbal A, Hagenbeek A, Petersen E et al. Identification of a 40S ribosomal protein S4-derived H-Y epitope able to elicit a lymphoblast-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte response. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11: 1694–1703.

Warren EH, Otterud BE, Linterman RW, Brickner AG, Engelhard VH, Leppert MF et al. Feasibility of using genetic linkage analysis to identify the genes encoding T cell-defined minor histocompatibility antigens. Tissue Antigen 2002; 59: 293–303.

Bleakley M, Otterud BE, Richardt JL, Mollerup AD, Hudecek M, Nishida T et al. Leukemia-associated minor histocompatibility antigen discovery using T-cell clones isolated by in vitro stimulation of naive CD8+ T cells. Blood 2010; 115: 4923–4933.

Spaapen R, Mutis T . Targeting haematopoietic-specific minor histocompatibility antigens to distinguish graft-versus-tumour effects from graft-versus-host disease. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2008; 21: 543–557.

Marijt WA, Heemskerk MH, Kloosterboer FM, Goulmy E, Kester MG, van der Hoorn MA et al. Hematopoiesis-restricted minor histocompatibility antigens HA-1- or HA-2-specific T cells can induce complete remissions of relapsed leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100: 2742–2747.

Fourcade J, Sun Z, Pagliano O, Guillaume P, Luescher IF, Sander C et al. CD8(+) T cells specific for tumor antigens can be rendered dysfunctional by the tumor microenvironment through upregulation of the inhibitory receptors BTLA and PD-1. Cancer Res 2012; 72: 887–896.

Gajewski TF, Meng Y, Harlin H . Immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunother 2006; 29: 233–240.

Jacobs JF, Nierkens S, Figdor CG, de Vries I, Adema GJ . Regulatory T cells in melanoma: the final hurdle towards effective immunotherapy? Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: e32–e42.

Hambach L, Nijmeijer BA, Aghai Z, Schie ML, Wauben MH, Falkenburg JH et al. Human cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for a single minor histocompatibility antigen HA-1 are effective against human lymphoblastic leukaemia in NOD/scid mice. Leukemia 2006; 20: 371–374.

Spaapen RM, Groen RW, van den Oudenalder K, Guichelaar T, van Elk M, Aarts-Riemens T et al. Eradication of medullary multiple myeloma by CD4+ cytotoxic human T lymphocytes directed at a single minor histocompatibility antigen. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16: 5481–5488.

Warren EH, Fujii N, Akatsuka Y, Chaney CN, Mito JK, Loeb KR et al. Therapy of relapsed leukemia after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with T cells specific for minor histocompatibility antigens. Blood 2010; 115: 3869–3878.

Acknowledgements

We thank Joyce van Kuijk, Bart Pelt and Rowena Melchers for their technical assistance in the qPCR analyses and Nening Nanlohy for her technical assistance in the tetramer production. This work was supported by grants from the Dutch Cancer Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Leukemia website

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Oostvogels, R., Minnema, M., van Elk, M. et al. Towards effective and safe immunotherapy after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: identification of hematopoietic-specific minor histocompatibility antigen UTA2-1. Leukemia 27, 642–649 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2012.277

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2012.277

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Efficacy of host-dendritic cell vaccinations with or without minor histocompatibility antigen loading, combined with donor lymphocyte infusion in multiple myeloma patients

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2017)

-

Minor histocompatibility Ags: identification strategies, clinical results and translational perspectives

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2016)

-

Effect of mismatching for mHA UTA2-1 on clinical outcome after HLA-identical sibling donor allo-SCT

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2015)