Abstract

We have recently isolated tirandamycin (TAM) B from Streptomyces sp. 17944 as a Brugia malayi AsnRS (BmAsnRS) inhibitor that efficiently kills the adult B. malayi parasites and does not exhibit general cytotoxicity to human hepatic cells. We now report (i) the comparison of metabolite profiles of S. sp. 17944 in six different media, (ii) identification of a medium enabling the production of TAM B as essentially the sole metabolite, and with improved titer, and (iii) isolation and structural elucidation of three new TAM congeners. These findings shed new insights into the structure–activity relationship of TAM B as a BmAsnRS inhibitor, highlighting the δ-hydroxymethyl-α,β-epoxyketone moiety as the critical pharmacophore, and should greatly facilitate the production and isolation of sufficient quantities of TAM B for further mechanistic and preclinical studies to advance the candidacy of TAM B as an antifilarial drug lead. The current study also serves as an excellent reminder that traditional medium and fermentation optimization should continue to be very effective in improving metabolite flux and titer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lymphatic filariasis, also known as elephantiasis, is caused primarily by two related parasites, Brugia malayi and Wuchereria bancrofti, and represents a worldwide health crisis with over 200 million people infected and another 20% of the global population at risk of infection.1 The asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase (AsnRS) in B. malayi is considered an excellent antifilarial target because (i) it is highly expressed in all stages of the parasite life cycle, (ii) it is biochemically and structurally well characterized and (iii) it shows significant structural differences in comparison with human and other eukaryotic aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases.2, 3, 4, 5 As part of a drug-discovery program targeting B. malayi AsnRS (BmAsnRS), we recently completed a high-throughput screening campaign of ∼73 000 microextracts, from a collection of 36 720 microbial strains, for activity against the recombinant BmAsnRS.5 Subsequent bioassay-guided dereplication of two of the active strains resulted in the discovery of two natural product scaffolds, represented by tirandamycin (TAM) B (1) from Streptomyces sp. 179446 and the depsipeptide WS9326D from Streptomyces sp. 9078,7 as promising antifilarial drug leads that kill the adult B. malayi parasites at low nanomolar concentrations yet are not cytotoxic to human hepatic cells.

Under the original fermentation condition using the ISP-2 medium, 1 was produced as a minor metabolite of S. sp. 17944. Preliminary fermentation optimization improved 1 production, but still with TAM A (2) as the major metabolite together with TAM E (3), F (4) and G (5) as co-metabolites.6 In this study, we sought out medium optimization to increase 1 titer and to produce 1 as the major metabolite to facilitate the production and isolation of sufficient quantities of 1 for further mechanistic and preclinical studies, in an effort to advance the candidacy of 1 as an antifilarial drug lead. Here we now report (i) the comparison of metabolite profiles of S. sp. 17944 in six different media, (ii) identification of a medium enabling the production of 1 as essentially the sole metabolite and with improved titer, and (iii) isolation and structural elucidation of three new TAM congeners, H (6), I (7) and J (8), shedding new insights into the structure–activity relationship of 1 as a BmAsnRS inhibitor and an antifilarial drug lead.

Results

Cloning of tamI from and development of a genetic system for S. sp. 17944

Five TAM producers are known, including three Streptomyces species of terrestrial origin, Streptomyces tirandis,8 Streptomyces flaveolus9 and S. sp. 17944,6 and two of marine origin, Streptomyces sp. 307-910 and Streptomyces sp. SCSIO 1666.11 The TAM biosynthetic gene cluster has been cloned from S. sp. 307-9 (named as the tam cluster)12 and S. sp. SCSIO 1666 (named as the trd cluster).13 The deduced TAM biosynthetic machinery features the TAM hybrid polyketide synthase (PKS)-nonribosomal peptide synthase (NRPS) responsible for the TAM backbone and the TamI P-450 oxygenase responsible for most of the post-hybrid PKS-NRPS oxidative tailoring modification steps (Figure 1).12, 13, 14, 15, 16 We cloned the tamI gene from S. sp. 17944 by PCR with primers designed according to the tam cluster of S. sp. 307-9.10 Although the tamI/trdI genes from the two marine Streptomyces species are identical, the tamI gene from S. sp. 17944 is highly homologous to its marine orthologs but with subtle variations (95% identity at DNA sequence/97% identity at amino-acid sequence), consistent with its terrestrial origin (Supplementary Figure S1).

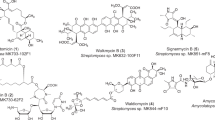

Proposed TAM biosynthetic pathway in S. sp. 17944, featuring the TAM hybrid PKS-NRPS and the TamI P-450 oxygenase as the key oxidative tailoring enzyme, that accounts for the formation of all TAM congeners isolated to date. TAMs 1–8 were isolated from S. sp. 17944 wild-type, whereas TAMs 9–13 were from S. sp. 307-9 and S. sp. SCSIO 1666 wild-type or mutant strains.

S. sp. 17944 sporulates optimally on ISP-4 agar plates and grows well in TSB as a liquid culture. Among the common antibiotics used for genetic manipulation of natural product biosynthesis in Streptomyces,17 S. sp. 17944 is sensitive to apramycin (25 μg ml−1), chloramphenicol (25 μg ml−1), gentamycin (50 μg ml−1), kanamycin (100 μg ml−1), neomycin (30 μg ml−1), spectinomycin (50 μg ml−1) and thiostrepton (12.5 μg ml−1) (given in parenthesis are concentrations that completely inhibit growth) and resistant to erythromycin (10 μg ml−1), nalidixic acid (25 μg ml−1) and trimethoprim (25 μg ml−1) (given in parenthesis are concentrations that have no apparent inhibitory effect on growth), respectively. Therefore, apramycin (25 μg ml−1) and nalidixic acid (25 μg ml−1) were used to select the exconjugants via Escherichia coli ET12567 (pUZ8002)—S. sp. 17944 conjugation,17 using pSET15218 and pKC113918 as representative Streptomyces integrating and replicating plasmids, respectively. Conjugation between E. coli ET12567 (pUZ8002) and S. sp. 17944 occurred with high frequencies on MS agar plates freshly supplemented with 10 mM MgCl2,19 with exconjugant frequencies for pSET152 and pKC1139 at approximately 10−5 and 10−6, respectively.

Medium optimization of S. sp. 17944 for TAM production

S. sp. 17944 was grown in six media, with varying carbon and nitrogen sources, as well as metal ions, under the optimized fermentation conditions. The crude extracts were subjected to HPLC analysis to determine the TAM metabolite profiles, which varied significantly (Figure 2). Although the ISP-2 medium yielded a mixture of TAMs, with 2 as the major TAM metabolite, a similarly metabolite profile was observed for medium B. In contrast, medium 042 produced 1, and both media 038 and F afforded 2 essentially as the sole TAM metabolite, respectively. Finally, medium SLY significantly suppressed the production of 1 and 2, and accumulated instead 3 and 5 as the major metabolites, two TAMs only produced in trace quantities in the original ISP-2 medium, as well as at least three new TAMs as minor metabolites (Figure 2).

The titers of 1 in the six media were determined on the basis of HPLC analysis calibrated with an authentic 1 standard (Table 1). Under the optimized fermentation conditions using medium 042, 1 can be produced essentially as the sole TAM metabolite with a titer at approximately 22 mg l−1.

Isolation and structural elucidation of the new TAM congeners from S. sp 17944

The varying TAM profiles upon fermenting S. sp. 17944 in the six media provided an excellent opportunity to isolate new TAM congeners that would not be produced in the original ISP-2 medium (Figure 2). A large-scale fermentation of S. sp. 17944 in medium SLY (6 l), followed by multiple steps of SiO2, Sephadex LH-20 and preparative C-18 chromatography, afforded three new TAM congeners, 6 (8.7 mg), 7 (6.9 mg) and 8 (2.8 mg).

The molecular formula of 6 was deducted as C22H29NO8 based on the high resolution electrosporay ionization mass spectrometry (HRESIMS) spectrum that gave [M+H]+ and [M+Na]+ ions at m/z 436.1989 and 458.1811 (calculated [M+H]+ and [M+Na]+ ions at m/z 436.1971 and 458.1790), respectively. Comparison of the 1H and 13C data (Table 2) of 6 with previously reported TAM congeners6 indicated a close structural similarity among these compounds, which is further confirmed by the consistent appearance of the geminal protons of the tetramic acid methylene carbon and the olefinic and methyl signals of the dienoyl acyl chain (Figure 3). Thus, COSY and HMBC correlations of 6 demonstrated a close identity to 3, which was isolated previously from S. sp. 17944.6 The disappearance of the H3-18 signal with the concomitant appearance of oxymethylene moiety (δC 59.1, C-18 and δH 4.43 and 4.31, H2-18) (Table 2), which is also supported by the 16-mass unit difference from 6 and 3, suggests that 6 is likely a C-10 hydroxylated congener of 3. This new moiety was further confirmed by the gHMBC correlations of H2-18 with C-11 (δC 61.3), C-12 (δC 60.2) and C-13 (δC 96.7) (Figure 3). As the absolute stereochemistry of 2 was known,6, 20 6, named as TAM H, was assigned the same stereochemistry as 2 on the basis of its biosynthetic origin (Figure 1).

HRESIMS analysis of 7 yielded [M+H]+ and [M+Na]+ ions at m/z 582.2583 and 604.2405, respectively, predicting a molecular formula of C28H39NO12 (calculated [M+H]+ and [M+Na]+ ions at m/z 582.2550 and 604.2369, respectively). The 13C NMR data of 7 (Table 1) was very similar to those of 36 with the exception of extra six resonances, which indicated an additional hexose moiety. The structure of the aglycone moiety was further confirmed to be 3 by key COSY and HMBC correlations (Figure 3). The hexose moiety was established by a one-dimensional TOCSY experiment, verified to be a glucoside by gHSQC, gHMBC, gCOSY and TOCSY correlations, and further confirmed to be an α-glucoside by comparison with previously reported NMR data and analysis of the coupling constant for the anomeric proton H-1′′ (δc 5.51, d, J=2.4 Hz) (Table 2).21, 22 The glucosidic linkage was established at position C-10 by the gHMBC correlation of the anomeric proton H-1′′ (δH 5.51) to C-10 (δC 71.3). This was further supported by the NOESY correlations between H-10 (δH 4.83) and H-1′′ (δH 5.51), which also showed correlations with H-3′′ (δH 4.47) and H-5′′ (δH 4.34), confirming the α-D-glucoside configuration (Figure 3). On the basis of these data, 7 was assigned as TAM I, a TAM E-10-α-D-glucoside with its absolute stereochemistry inferred from biosynthesis (Figure 1).

The molecular formula C30H37NO12 for 8 was established on the basis of HRESIMS analysis that afforded [M+H]+ and [M+Na]+ ions at m/z 596.2376 and 618.2198 (calculated [M+H]+ and [M+Na]+ ions at m/z 596.2343 and 618.2162), respectively. Careful comparison of the 1H and 13C NMR data of 8 (Table 2) with previously reported TAM congeners revealed a close identity to 1 with an additional hexose moiety. The latter was confirmed to be an α-glucoside by comparison with NMR data of the hexose moiety of 7 (Table 2), the coupling constant of the anomeric proton H-1′′ (δc 5.47, d, J=2.5 Hz), and the COSY and TOCSY correlations. Thus, the glucosidic linkage was established at position C-18 by the gHMBC correlation of the anomeric proton H-1′′ (δH 5.47) to C-18 (δC 57.8). This was further supported by the NOESY correlations between H2-18 (δH 4.68, 4.13) and H-1′′ (δH 5.47) (Figure 3). These data allowed the final assignment of 8 as TAM J, a TAM B-18-α-D-glucoside with its absolute stereochemistry similarly deduced on the base of biosynthesis (Figure 1).

Evaluation of 6, 7 and 8 for BmAsnRS-inhibitory activity

The three new TAM congeners, 6, 7 and 8, were evaluated for their BmAsnRS-inhibitory activity following the previous procedure6 with 1 as a positive control. None of the congeners showed any apparent inhibitory activity at 200 μM.

Discussion

First isolated in the 1970s from S. tirandis8 and S. flaveolus,9 1 and 2 were originally discovered as bacterial RNA polymerase inhibitors.23 It was not until very recently, 1 and 2 were rediscovered from the marine S. sp. 307-9 during the screen for activity against vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis,10 together with two new congeners, TAM C (9) and D (10), from marine S. sp. SCSIO 166611 in an effort to discover new bacterial RNA polymerase inhibitors, together with TAM C2 (11), and from S. sp. 17944 in our current program to discover BmAsnRS inhibitors as antifilarial drug leads,6 together with the three congeners 3, 4 and 5, previously, and three additional congeners, 6, 7 and 8, in this study. During the characterization of the TAM biosynthetic machinery in S. sp. 307-912 and S. sp. SCSIO 166613, 15, 16 and in vitro characterization of the TamI P-450 oxygenase,13 a biosynthetic intermediate, 12, was isolated, which unfortunately were given two different names concurrently, TAM F and TAM E. This nomenclature was further complicated by the fact that both TAM F and TAM E were concurrently taken for 3 and 4, respectively, from S. sp. 17944.6 In an attempt to eliminate these confusion, we now propose to reserve TAM E and F for 3 and 4, respectively, and rename 12 as TAM C1 following the precedence of TAM C2 for 11.15 Finally, in vivo characterization of trdE in S. sp. SCSIO 1666 and in vitro study of TrdE resulted in the identification of pre-TAM (13) as the nascent intermediate of the TAM hybrid PKS-NRPS.16 Taken together, a total of 13 TAM congeners have been isolated from the five producers (Figure 1).

The cloning and sequencing of the TAM biosynthetic gene cluster from S. sp. 307-912 and S. sp. SCSIO 1666,13, 15, 16 respectively, opened the possibility to manipulate the TAM biosynthetic machinery for TAM production. The TAM biosynthetic pathway features the TAM hybrid PKS-NRPS for the biosynthesis of 13, which is first dehydrated by TrdE to afford 9 and subsequently oxidized sequentially by TamI and TamL, via the intermediacy of 11/12, 10 and 2, to 1, and this pathway is supported by the isolation of all the proposed biosynthetic intermediates from S. sp. 307-9 and S. sp. SCSIO 1666 wild-type and mutant strains.12, 13, 14, 15, 16 In a biosynthetic analogy to S. sp. 307-9 and S. sp. SCSIO 1666, the same pathway for TAM biosynthesis could be proposed in S. sp. 17944, with additional tailoring steps to account for the formation of 3–8 (Figure 1). Thus, although the formation of 3, 4 and 5 from 2 could have resulted from adventitious reductase activities, hydroxylation of 3 to 6 would be consistent with the broad substrate specificity known for TamI.14 The fact that 6 is not detected when 1 is the dominate metabolite and isolated only when 3 is produced in high yield further supports 3, rather than 1, as the likely precursor for 6 (Figures 1 and 2). Bioinformatics analysis of the tam and trd clusters from S. sp. 307-912 and S. sp. SCSIO 166614 has failed to unveil any candidate potentially conferring TAM self-resistance to the producing Streptomyces. Although no gene-encoding glucosyltransferase was identified within the cloned tam and trd cluster, it is tempting to speculate that glucosylation may represent one of the resistance mechanisms in S. sp. 17944 as exemplified by the isolation of 7 and 8.22 Finally, TamI plays the fundamental role in catalyzing minimally three steps of oxidations in 1 biosynthesis,12, 13, 14 and overexpression of tamI, thereby channeling all the biosynthetic intermediates to completion, therefore would represent an outstanding opportunity to engineer a 1 overproducer (Figure 1). Strategies of overexpressing genes controlling rate-limiting steps to alter the metabolic flux or manipulating pathway regulation for titer improvement have been well demonstrated and successfully exploited for the production of targeted metabolites.24, 25, 26, 27 Although our success in medium optimization and identification of conditions for S. sp 17944 to produce 1 exclusively with good titer neglects the need to consider genetic approaches to alter metabolic flux and improve metabolite titer, cloning of the tamI gene and development of an expedient genetic system for S. sp. 17944 in the current study certainly set the stage for such endeavor if they are justified by future needs.

The discovery of 1 as a novel BmAsnRS inhibitor, which efficiently kills the adult B. malayi parasites and does not exhibit general cytotoxicity to human hepatic cells, underscores the great potential of our innovative high-throughput screening, targeting BmAsnRS for antifilarial drug discovery.6, 7 The microbial origin of these leads promises that they can be produced in sufficient quantities by scale-up fermentation and their biosynthetic machinery could be subjected to combinatorial biosynthetic strategies for titer improvement and structural diversity, greatly facilitating follow-up mechanistic and preclinical studies.28 The current study also serves as an excellent reminder that traditional medium and fermentation optimization could remain very effective in improving metabolite flux and titer, as exemplified by the exclusive production of 1 in good titer upon fermenting S. sp. 17944 in the 042 medium. Medium optimization of S. sp. 17944 fermentation also enabled the production, thereby isolation and characterization, of three new TAM congeners, 6, 7 and 8. These new TAM congeners not only shed new insight into TAM biosynthesis and potential mechanisms of resistance but also further support to the structure–activity relationship of TAMs—(i) the δ-hydroxymethyl-α,β-epoxyketone moiety is critical for the BmAsnRS-inhibitory activity, as highlighted by 1, and (ii) reduction of carbonyl group at C-10, as in 6, or the glucosylation of the hydroxymethyl group at C-18, as in 8, completely abolishes the activity.6

Methods

Cloning of tamI from and development of a genetic system for S. sp. 17944

The tamI gene was cloned by PCR from S. sp. 17944 using the primers, TamI-S, 5′-GTGCCCATGCTTCAGGATTCAGTCC-3′ and TamI-A, 5′-CTATGGGCGGTTCAGCCGCACCGGC-3′, designed according to the tamI locus of S. sp. 307-9.10 A distinct product with the predicted size of 1242 bp was obtained, cloned into pGEM-T and sequenced to confirm its identity as tamI, which has been deposited in GenBank under the accession number KC820795.

S. sp. 17944 was grown on ISP-417 agar plates for sporulation and in TSB17 for liquid culture. S. sp. 17944 sensitivity to the selected antibiotics was determined on ISP-217 agar plates at two concentrations of apramycin (25/50 μg ml−1), chloramphenicol (25/50 μg ml−1), erythromycin (10/20 μg ml−1), gentamycin (50/100 μg ml−1), kanamycin (100/200 μg ml−1), nalidixic acid (25/50 μg ml−1), neomycin (30/69 μg ml−1), spectinomycin (50/100 μg ml−1), thiostrepton (12.5/25 μg ml−1) and trimethoprim (25/50 μg ml−1), respectively, according to literature procedure.17 E. coli ET12567 (pUZ8002)—S. sp. 17944 conjugation, using pSET15218 and pKC1139,18 was carried out following the standard protocol,17 and exconjugants were selected on MS plates,17 freshly supplemented with 10 mM MgCl2,19 with apramycin (25 μg ml−1)/nalidixic acid (25 μg ml−1). Single colonies were then grown in TSB with apramycin (25 μg ml−1) and confirmed to carry pSET152 or pKC1139 by PCR amplification of the apramycin-resistance gene aac(3)IV using primers 5′-CCTTGGAGTTGTCTCTGACACAT-3′and 5′-GATGCAGGAAGATCAACGGATCT-3′.17, 18

Medium optimization of S. sp. 17944 for TAM production

S. sp. 17944 was preserved as spore solutions at −80 °C. To prepare the seed culture, a 18-ml tube, containing 5 ml of ISP-2, was inoculated with 10 μl of the spore solution and incubated with shaking (250 r.p.m.) at 28.0 °C for 3 days. To carry out medium optimization, 250-ml baffled Erlenmeyer flasks, each containing 50 ml of varying medium, were inoculated with 1 ml of the seed culture and grown at 28.0 °C for 7 days with shaking (250 r.p.m.). The six media were B, F, ISP-2, 038, 042 and SLY.22, 26

B: soluble starch 5.0 g, glucose 20.0 g, peptone 2.0 g, yeast extract 2.0 g, soybean flour 10.0 g, NaCl 4.0 g, K2HPO4 0.5 g, MgSO4.7H2O 0.5 g and CaCO3 2 g in 1 l distilled water, pH 7.8.

F: sucrose 100 g, glucose 10.0 g, casamino acids 0.1 g, yeast extract 5.0 g, MOPS 21.0 g, *trace element 1 ml, K2SO4 0.25 g and MgCl2.6H2O 10.0 g in 1 l distilled water, pH 7.0.

ISP-2: yeast extract 4.0 g, malt extract 10.0 g and dextrose 4.0 g in 1 l distilled water, pH 7.2.

038: mannitol 22 g, glycerol 3 g, peptone 4 g, casamino acids 1 g, yeast extract 1.5g, MgSO4.7H2O 0.3 g, K2HPO4 0.5 g, NaCl 1.0 g, KNO3 0.25 g, FeSO4.7H2O 0.01 g and *trace element 1 ml in 1 l distilled water, pH 7.0.

042: glucose 10.0 g, corn starch 10.0 g, glycerol 10.0 g, corn steep 2.5 g, peptone 5.0 g, yeast extract 2.0 g, NaCl 1.0 g and CaCO3 3.0 g in 1 l distilled water, pH 7.2.

SLY: Stadex 60k dextrin 40.0 g, lactose 40.0 g and yeast extract 5.0 g in 1 l distilled water, pH 7.0.

*Trace element solution: MnSO4.7H2O 100 mg, CuSO4.5H2O 50 mg, ZnSO4.7H2O 100 mg and CoCl2 100 mg in 100 ml distilled water.

XAD-16 resins (2.5 g) were added to each of the production flasks before TAM isolation, and fermentation continued for additional 4 h.6 Each flask was then transferred to a 50-ml tube and centrifuged to pellet the resins/cells in the bench-top centrifuge. The resulting resins/cells were washed with 20 ml distilled water twice, frozen on dry ice and lyophilized to dryness overnight. The dry resins/cells were extracted with 20 ml MeOH twice, and the combined MeOH extracts were concentrated in vacuo to afford the crude extracts. Each of the crude extracts was dissolved in 3 ml DMSO, and 10 μl of the resultant DMSO solutions were subjected to HPLC analysis with an Apollo C-18 column (5 μm; 4.6 × 250 mm2; Grace Davison Discovery Sciences, Deerfield, IL, USA). The column was developed with a 30-min gradient from 15% CH3CN in 0.1% HCO2H to 100% CH3CN at flow rate of 1 ml min−1 and UV detection at 351 nm. Titers of 1 in each medium were the average of two independent fermentations as determined by HPLC analysis calibrated with an authentic 1 standard.6

Isolation and structural elucidation of new TAM congeners from S. sp. 17944

To prepare the seed culture, eight 250-ml baffled Erlenmeyer flasks, each containing 50 ml of ISP-2, were inoculated with 10 μl of the S. sp. 17944 spore solution and incubated with shaking (250 r.p.m.) at 28.0 °C for 2 days. Fifteen 2-l baffled Erlenmeyer flasks, each containing 400 ml of SLY medium, were then inoculated with 25 ml of the seed culture each and grown for 7 days under the same fermentation condition. The production cultures were centrifuged at 5000 r.p.m. and 4 °C for 30 min to collect the mycelia, and the broth was extracted with 3% Amberlite XAD-16 resins (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), which were collected by centrifugation. The mycelia and resins were combined and extracted three times with methanol. The combined methanol elution was then concentrated in vacuo to afford the crude extract (4.2 g).6 This material was subjected to SiO2 chromatography, eluted step-wise with CHCl3:CH3OH (100:0, 50:1, 20:1, 10:1, 5:1 and 0:100, 1 l each) as the mobile phase, to afford eight fractions, A–H. Fraction F (608 mg) was further chromatographed over Sephadex LH-20 column (Sigma-Aldrich), eluted with CH3OH to yield four sub-fractions, F1–F4. F3 was finally purified by semipreparative HPLC to afford pure 6 (8.7 mg), 7 (6.9 mg) and 8 (2.8 mg), in addition to 1 and 2.

TAM H (6): yellow oil; [α]20D −12.4° (c 0.87, EtOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ɛ) at 213 (4.2) and 351 (2.7) nm; 1H and 13C NMR data (Table 2); HRESIMS m/z [M+H]+ and [M+Na]+ at 436.1989 and 458.1811 (calculated [M+H]+ and [M+Na]+ ions at m/z 436.1971 and 458.1790), respectively.

TAM I (7): yellow oil; [α]20D +81.2° (c 0.69, EtOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ɛ) at 213 (4.2) and 351 (2.7) nm; 1H and 13C NMR data (Table 2); HRESIMS m/z [M+H]+ and [M+Na]+ at 582.2583 and 604.2405 (calculated [M+H]+ and [M+Na]+ ions at m/z 582.2550 and 604.2369), respectively.

TAM J (8): yellow oil; [α]20D +11.4° (c 0.28, EtOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ɛ) at 213 (4.2) and 351 (2.7) nm; 1H and 13C NMR data (Table 2); HRESIMS m/z [M+H]+ and [M+Na]+ at 596.2376 and 618.2198 (calculated [M+H]+ and [M+Na]+ ions at m/z 596.2343 and 618.2162), respectively.

Evaluation of 6, 7 and 8 for BmAsnRS-inhibitory activity

Evaluation of 6, 7 and 8 for BmAsnRS-inhibitory activity, with 1 as a positive control, followed the previously described procedure.6

Accession codes

References

Dzenowagis, J. Lymphatic Filariasis: Reasons for Hope, World Health Organization: Geneva, (1997).

Kron, M., Marquard, K., Hartlein, M., Price, S. & Lederman, R. An immunodominant antigen of Brugia malayi is an asparaginyl-transfer-RNA synthetase. FEBS Lett. 374, 122–124 (1995).

Nilsen, T. W. et al. Cloning and characterization of a potentially protective antigen in lymphatic filariasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85, 3604–3607 (1988).

Danel, F. et al. Asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase pre-transfer editing assay. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 8, 66–75 (2011).

Crepin, T. et al. A hybrid structural model of the complete Brugia malayi cytoplasmic asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Mol. Biol. 405, 1056–1069 (2011).

Yu, Z. et al. Tirandamycins from Streptomyces sp.17944 inhibiting the parasite Brugia malayi asparagine tRNA synthetase. Org. Lett. 13, 2034–2037 (2011).

Yu, Z. et al. New WS9326A congeners from Streptomyces sp. 9078 inhibiting Brugia malayi asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase. Org. Lett. 14, 4946–4949 (2012).

Meyer, C. E. Tirandamycin a new antibiotic isolation and characterization. J. Antibiot. 24, 558–560 (1971).

Hagenmaier, H., Jaschke, K. H., Santo, L., Scheer, M. & Zahner, H. Metabolic products of microorganisms.158. Tirandamycin-B. Arch. Microbiol. 109, 65–74 (1976).

Carlson, J. C., Li, S. Y., Burr, D. A. & Sherman, D. H. Isolation and characterization of tirandamycins from a marine-derived Streptomyces sp. J. Nat. Prod. 72, 2076–2079 (2009).

Duan, C. et al. Fermentation optimization, isolation and identification of tirandamycins A and B from marine-derived Streptomyces sp. SCSIO 1666. Chin. J. Mar. Drugs 29, 12–20 (2010).

Carlson, J. C. et al. Identification of the tirandamycin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces sp. 307-9. ChemBioChem. 11, 564–572 (2010).

Mo, X. et al. Cloning and characterization of the biosynthetic gene cluster of the bacterial RNA polymerase inhibitor tirandamycin from marine-derived Streptomyces sp. SCSIO1666. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 406, 341–347 (2011).

Carlson, J. C. et al. Tirandamycin biosynthesis is mediated by co-dependent oxidative enzymes. Nat. Chem. 3, 628–633 (2011).

Mo, X. et al. Characterization of TrdL as a 10-hydroxy dehydrogenase and generation of new analogues from a tirandamycin biosynthetic pathway. Org. Lett. 13, 2212–2215 (2011).

Mo, X. et al. Δ11,12 Double bond formation in tirandamycin biosynthesis is atypically catalyzed by TrdE, a glycoside hydrolase family enzyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 2844–2847 (2012).

Kieser, T., Bibb, M. J., Buttner, M. J., Chater, K. F. & Hopwood, D. A. Practical Streptomyces Genetics, John Innes Foundation: Norwich, United Kingdom, (2000).

Bierman, M. et al. Plasmid cloning vectors for the conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces spp. Gene 116, 43–49 (1992).

Liu, W. & Shen, B. Genes for production of the enediyne antitumor antibiotic C-1027 in Streptomyces globisporus are clustered with the cagA gene that encodes the C-1027 apoprotein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 382–392 (2000).

Duchamp, D. J., Branfman, A. R., Button, A. C. & Rinehart, K. L. X-ray structure of tirandamycic acid para-bromophenacyl ester—complete stereochemical assignments of tirandamycin and streptolydigin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95, 4077–4078 (1973).

Duus, J., Gotfredsen, C. H. & Bock, K. Carbohydrate structural determination by NMR spectroscopy: modern methods and limitations. Chem. Rev. 100, 4589–4614 (2000).

Yu, Z., Rateb, M. E., Smanski, M. J., Peterson, R. M. & Shen, B. Isolation and structural elucidation of glucoside congeners of platencin from Streptomyces platensis SB12600. J. Antibiot. 66, 291–294 (2013).

Reusser, F. Tirandamycin, an inhibitor of bacterial ribonucleic-acid polymerase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 10, 618–622 (1976).

Sezonov, G. et al. Complete conversion of antibiotic precursor to pristinamycin IIA by overexpression of Streptomyces pristinaespiralis biosynthetic genes. Nat. Biotechnol. 15, 349–363 (1997).

Chen, Y., Wendt-Pienkowski, E. & Shen, B. Identification and utilities of FdmR1 as a SARP activator for fredericamycin production in Streptomyces griseus ATCC49344 and heterologous hosts. J. Bacteriol. 190, 5587–5596 (2008).

Smanski, M. J., Peterson, R. M., Rajski, S. R. & Shen, B. Engineered Streptomyces platensis strains that overproduce antibiotics platensimycin and platencin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 1299–1304 (2009).

Chen, Y., Smanski, M. J. & Shen, B. Improvement of secondary metabolite production in Streptomyces by manipulating pathway regulation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 86, 19–25 (2010).

Van Lanen, S. & Shen, B. Microbial genomics for the improvement of natural product discovery. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9, 252–260 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIH Grants AI053877 (to MAK) and GM086184 (to BS), as well as the Natural Products Library Initiative at TSRI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Dedicated to Professor Christopher T Walsh, Harvard Medical School, for his enormous impact on the field of antibiotic and microbial natural product biosynthesis.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on The Journal of Antibiotics website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rateb, M., Yu, Z., Yan, Y. et al. Medium optimization of Streptomyces sp. 17944 for tirandamycin B production and isolation and structural elucidation of tirandamycins H, I and J. J Antibiot 67, 127–132 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ja.2013.50

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ja.2013.50

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Metabolic engineering strategies for naringenin production enhancement in Streptomyces albidoflavus J1074

Microbial Cell Factories (2023)

-

Technical Advances to Accelerate Modular Type I Polyketide Synthase Engineering towards a Retro-biosynthetic Platform

Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering (2019)

-

Short-chain ketone production by engineered polyketide synthases in Streptomyces albus

Nature Communications (2018)

-

Asparagine requirement in Plasmodium berghei as a target to prevent malaria transmission and liver infections

Nature Communications (2015)