Abstract

Organohalide-respiring bacteria have key roles in the natural chlorine cycle; however, most of the current knowledge is based on cultures from contaminated environments. We demonstrate that grape pomace compost without prior exposure to chlorinated solvents harbors a Dehalogenimonas (Dhgm) species capable of using chlorinated ethenes, including the human carcinogen and common groundwater pollutant vinyl chloride (VC) as electron acceptors. Grape pomace microcosms and derived solid-free enrichment cultures were able to dechlorinate trichloroethene (TCE) to less chlorinated daughter products including ethene. 16S rRNA gene amplicon and qPCR analyses revealed a predominance of Dhgm sequences, but Dehalococcoides mccartyi (Dhc) biomarker genes were not detected. The enumeration of Dhgm 16S rRNA genes demonstrated VC-dependent growth, and 6.55±0.64 × 108 cells were measured per μmole of chloride released. Metagenome sequencing enabled the assembly of a Dhgm draft genome, and 52 putative reductive dehalogenase (RDase) genes were identified. Proteomic workflows identified a putative VC RDase with 49 and 56.1% amino acid similarity to the known VC RDases VcrA and BvcA, respectively. A survey of 1,173 groundwater samples collected from 111 chlorinated solvent-contaminated sites in the United States and Australia revealed that Dhgm 16S rRNA genes were frequently detected and outnumbered Dhc in 65% of the samples. Dhgm are likely greater contributors to reductive dechlorination of chlorinated solvents in contaminated aquifers than is currently recognized, and non-polluted environments represent sources of organohalide-respiring bacteria with novel RDase genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chlorinated hydrocarbons have been widely used in different areas of modern societies, such as cleaning of machinery, manufacturing, and agrochemical production (for example, pesticides) (McCarty, 2010). Widespread usage and uncontrolled disposal of chlorinated hydrocarbons pose substantial environmental and human health concerns. For example, the widely used chlorinated solvent trichloroethene (TCE) is carcinogenic (Wartenberg et al., 2000) and has been implicated in Parkinson’s disease (Goldman et al., 2012). Vinyl chloride (VC), a TCE transformation product, is a notorious groundwater contaminant and a proven human carcinogen (Kielhorn et al., 2000). TCE and VC are ranked #16 and #4 on the Substance Priority List (SPL) and have been detected in 1153 and 593 Superfund sites, respectively (www.atsdr.cdc.gov/spl/resources/index.html). The frequent detection of these hazardous chlorinated compounds in aquifers is disconcerting, and the discovery of organohalide-respiring bacteria was a landmark achievement, laying the foundation for in situ bioremediation (Löffler and Edwards, 2006). Diverse microorganisms, including members of the genera Dehalobacter, Dehalococcoides, Desulfitobacterium, Desulfuromonas, Geobacter and Sulfurospirillum were isolated and demonstrated the ability to degrade PCE and TCE (Adrian and Löffler, 2016). Interestingly, the reductive dechlorination of chlorinated ethenes to non-toxic ethene has been attributed exclusively to Dehalococcoides mccartyi (Dhc) strains (Löffler et al., 2013b), and a few reductive dehalogenase (RDase) genes have been implicated in the detoxification of chlorinated ethenes (Hug et al., 2013b). Consequently, contaminated site characterization, bioremediation monitoring, and decision making rely on the quantitative assessment of Dhc biomarker genes in groundwater or aquifer solids (Cápiro et al., 2014). Correlations between the presence and abundance of Dhc with the detoxification of chlorinated ethenes have been established; however, VC disappearance at sites lacking Dhc biomarkers has been observed (Lu et al., 2006), and the presence/absence of Dhc biomarker genes does not always explain dechlorination activity and ethene formation (Da Silva and Alvarez, 2008; He et al., 2015).

Information about microbial degradation of chlorinated ethenes has been almost exclusively derived from microorganisms obtained from contaminated environments. This approach was justified to derive process-relevant understanding for engineered bioremediation and site cleanup; however, more recent discoveries demonstrated that chlorinated hydrocarbons, including priority pollutants, also have natural origins (Gribble, 2010). For instance, even the human carcinogen VC can be generated abiotically in the soil environment, a process likely occurring since the first soils formed on Earth some 400 million years ago (Keppler et al., 2002). Apparently, VC has been part of the biosphere long before human activities affected environmental concentrations of this carcinogen. A recent study correlated the abundance of Dhc-like Chloroflexi with the quantity of natural organohalogens in soils, supporting the notion that the organohalide-respiring phenotype is not merely a consequence of anthropogenic activities (Krzmarzick et al., 2012).

Here we demonstrate PCE reductive dechlorination and ethene formation in microcosms established with grape pomace compost not previously exposed to chlorinated solvents. Characterization of the enrichment culture demonstrated that the ability to grow with VC as electron acceptor is not limited to members of the Dhc genus. These findings expand the current understanding of the bacterial diversity capable of metabolizing VC under anoxic conditions, provide an explanation for ethene formation in chlorinated solvent-contaminated aquifers in the absence of Dhc, and demonstrate that ecosystems without prior chlorinated solvent exposure are a source of specialized organohalide-respiring bacteria, which use priority pollutants as electron acceptors.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

PCE, TCE and carbon tetrachloride (CT) (all ⩾99% purity) were purchased from Acros Organics (Distributed by VWR International, West Chester, PA, USA). cDCE (>96.0% purity), VC (⩾99.5%), 1,2,3-trichloropropane (1,2,3-TCP) (99%), 1,2-dichloropropane (1,2-DCP) (99%), 1,2-dichloroethane (1,2-DCA) (99.8%), 1,1-dichloroethene (1,1-DCE) and ethene (⩾99.5%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other chemicals were of scientific grade or better, and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Microcosms and transfer cultures

Reduced, bicarbonate-buffered mineral salts medium with 5 mm lactate was prepared following established protocols (Löffler et al., 2005). Microcosms were established with grape pomace compost collected in the wine-growing area of Rotenberg near Stuttgart, Germany (Supplementary Figure 1; Supplementary Information). Duplicate microcosms amended with 2 μl neat tetrachloroethene (PCE) (19.5 μmol/bottle) were incubated statically at room temperature in the dark. Subsequent transfers (3%, vol/vol) with lactate and PCE yielded solid-free, ethene-producing enrichment cultures. In subcultures, 2 ml VC (83.0 μmol/bottle) replaced PCE as electron acceptor. To inhibit methanogenesis, 1.2 mm 2-bromoethanesulfonate (BES) was added. Live microcosms and transfer cultures were set up in at least duplicate. Negative controls included vessels that received no electron acceptor and autoclaved replicates of live incubations.

DNA extraction, PCR procedures and amplicon sequencing

DNA extraction and PCR assays targeting Dhc and Dhgm 16S rRNA genes and the tceA, bvcA and vcrA RDase genes followed established procedures (Ritalahti et al., 2006; Yan et al., 2009) and details are provided in the Supplementary Information. DNA extracted from PCE- and VC-fed culture GP (referring to the culture source, grape pomace) biomass was treated with the Genomic DNA Clean and Concentrator Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). Purified DNA samples were PCR-amplified using barcoded-primers F515/R806 targeting the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene. The amplicon sequencing approach followed established protocols (Caporaso et al., 2011, 2012). Raw sequences were paired and analyzed using the mothur software package (www.mothur.org) following MiSeq standard operating procedures (Schloss et al., 2009).

Quantitative real-time PCR assay

A TaqMan chemistry-based quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay was developed to specifically target and enumerate Dhgm 16S rRNA genes. The forward primer Dhgm478F (5′-AGCAGCCGCGGTAATACG-3′), the reverse primer Dhgm536R (5′-CCACTTTACGCCCAATAAATCC-3′) and the TaqMan probe Dhgm500Probe (5′-6FAM-AGGCGAGCGTTAT-MGB-3′) matching Dhgm 16S rRNA gene sequences, which were retrieved from NCBI database, were designed using the Primer3 plug-in in Geneious 8.1.7. The assay specificity was verified by in silico analysis using the Primer3 plug-in in Geneious 8.1.7 and the Primer-BLAST tool provided by NCBI, and was further experimentally confirmed using pure culture genomic DNA of Dhc strain 195 and strain FL2 and 171 bp-long synthesized DNA oligos containing the corresponding amplicon sequence of the Dhc 16S rRNA gene (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) (Supplementary Figure 3). All qPCR assays consisted of two-fold concentrated TaqMan Universal PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA), UltraPure nuclease-free water (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 300 nm probe, 300 nm of each primer, and a DNA template and were performed using an Applied Biosystems ViiA 7 system (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). The qPCR cycle conditions were as follows: 50 °C for 2 min and then held at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C. The standard curves were generated using three independent dilution series of plasmid DNA carrying a nearly complete sequence (1492 bp) of the Dhgm strain BL-DC-9 16S rRNA gene (NCBI accession NR_074337.1) or a 171 bp-long synthesized DNA oligo (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) covering the 59 bp amplicon region. This Dhgm qPCR assay standard curve had a slope of −3.676, a y-intercept of 40.97, a R2 value of 0.997, and a PCR amplification efficiency of 87.10% (Supplementary Figure 3). The detection limit is 11.4 gene copies per reaction, and the linear range spanned 1.14 × 102 to 1.14 × 108 gene copies per reaction.

Metagenome sequencing and comparative analyses

Metagenomic sequencing of the VC-grown enrichment culture GP was performed using the MiSeq platform provided through Center for Environmental Biotechnology (University of Tennessee Knoxville, Knoxville, TN, USA). The Nextera-prepped metagenome library with an average fragment size of 450 bp was sequenced using the v3 reagent kit for a 2x300 run. After being trimmed and filtered, the resulting 13 667 850 paired-end reads were assembled following established procedures (Oh et al., 2011) (see Supplementary Information for details). For a comparative metagenome analysis, the sequences of VC-fed culture GP (MG-RAST ID: 4625853.3) were uploaded to the MG-RAST server and compared with three PCE-/TCE-dechlorinating consortia KB-1 (MG-RAST ID: 4450840.3), ANAS (MG-RAST ID: 4451655.3) and Donna II (MG-RAST ID: 4451259.3). Metagenomic data sets from non-dechlorinating communities of an acid mine drainage site (Richmond Mine, Iron Mountain, CA; MG-RAST ID: 4441137.3 and 4441138.3) and a pristine freshwater lake in Antarctica (Ace Lake; MG-RAST ID: 4443683.3) were included in the analysis due to their well-documented meta information, good quality sequence reads, and their distinct origins. Taxonomic and functional annotation results from MG-RAST were imported into STAMP for principal component analysis (PCA) and visualization (Parks et al., 2014). Details about the PCA analysis are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Genome binning and annotation

Binning of metagenomic contigs was conducted with MetaWatt v1.7 (Strous et al., 2012) and VizBin (Laczny et al., 2015), using GC content, tetranucleotide frequency and coverage as quality metrics to assess consistency of contigs within the genomic bin (Laczny et al., 2015). Contigs belonging to the Dhgm bin were further assessed with CheckM (Parks et al., 2015) using default settings to further assess genome bin completeness, contamination and taxonomic affiliation. The draft genome bin was uploaded to RAST (Overbeek et al., 2014) for annotation (Accession ID: 1536648.4).

Phylogenetic analyses

Maximum likelihood tree estimation was performed using RAxML v8.2.5 (Stamatakis, 2014) on individual and concatenated 5S, 16S and 23S rRNA gene alignments with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Evolutionary model selection was evaluated with jModelTest v2.1.5 (Darriba et al., 2012). In all cases, the generalized time-reversible model (Tavaré, 1986) with estimations of the proportion of invariable sites and rate heterogeneity among sites (eight substitution rate categories) was implemented in RAxML. For concatenated alignments, a partition file was provided to RAxML and rate heterogeneity among partitions was estimated individually. The phylogenetic tree of RDase proteins was built using Geneious software with default settings of the MAFFT Alignment and Geneious Tree Builder tools.

Proteomics analysis

Proteins were extracted from culture GP grown with TCE, 1,1-DCE, cDCE and VC as electron acceptors and subjected to LC–MS/MS analysis following established procedures (Chourey et al., 2010, 2013). Biomass harvest times and detailed procedures are described in Supplementary Table 1 and the Supplementary Information.

Analytical methods

Chlorinated solvents were measured in 100 μl headspace gas samples with an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with an Agilent DB624 column and a flame ionization detector (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The concentrations of chlorinated ethenes were calculated by normalizing the peak areas to standard curves generated by adding known amounts of chlorinated ethenes and ethene into vessels with the same total volume and gas to liquid ratios. Gas samples (100 μl) were removed from the headspace using a gastight 250 μl Hamilton SampleLock syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV, USA) and manually injected into the GC. Chloride release was calculated based on the gas chromatographic chlorinated ethene/ethene concentration measurements, and assumed that each reductive dechlorination step liberates one chlorine substituent as inorganic chloride (Sung et al., 2006).

Dhc and Dhgm abundances in groundwater impacted with chlorinated solvents

DNA was extracted from groundwater (1173 samples) or biomass collected on site onto Sterivex cartridges (Ritalahti et al., 2010). Dhc 16S rRNA gene-targeted qPCR followed established procedures (Ritalahti et al., 2006; Yan et al., 2009) and Dhgm 16S rRNA genes were enumerated with the Dhgm478F-Dhgm500Probe-Dhgm536R assay (this study).

Sequence data deposition

Raw metagenome sequences of the VC-dechlorinating culture GP were deposited on MG-RAST servers under accession ID 4625853.3. The draft genome of ‘Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans’ strain GP was deposited to NCBI (accession number JQAN00000000 under BioProject SUB633157).

Results

Reductive dechlorination of chlorinated ethenes in grape pomace compost microcosms and transfer cultures

In anoxic grape pomace microcosms, PCE was reductively dechlorinated to ethene via TCE, cDCE, 1,1-DCE and VC as intermediates after a 300-day incubation period, and a similar dechlorination pattern was observed in transfer cultures (Supplementary Figure 2). Following the addition of BES, an inhibitor of methanogenesis, cDCE was the dechlorination end product and VC and ethene were not formed (data not shown). Without BES addition, the solid-free transfer cultures maintained the ability to produce ethene in defined, completely synthetic medium.

Comparison between PCE- and VC-fed enrichment cultures

To identify the population(s) responsible for the observed dechlorination activity, DNA was extracted from ethene-producing PCE- and VC-fed cultures for 16S rRNA gene amplicon profiling. No evidence for the presence of Dhc 16S rRNA gene sequences was obtained, a finding supported by targeted PCR analyses, which failed to detect the Dhc 16S rRNA gene and the tceA, bvcA, and vcrA RDase genes implicated in reductive dechlorination of chlorinated ethenes (data not shown). Instead, Dhgm 16S rRNA gene fragments dominated the sequence pool, and represented 43.9 and 46.1% of all bacterial sequences in the PCE-fed and in VC-fed cultures, respectively (Figure 1). Also detected were sequences of not-yet-cultured bacteria of the WWE1 and WPS-2 candidate divisions, which represented 3.6% and 8.3% of the PCE-fed and 2.6% and 9.4% of the VC-fed communities, respectively. Sequences assigned to the genera Clostridium, Pelotomaculum, Treponema, Sedimentibacter, as well as the unclassified groups HA73 of Dethiosulfovibrionaceae and vadinCA02 of Synergistaceae, were all present at >1% abundances in both PCE- and VC-fed communities.

Community structure of PCE-fed and VC-fed grape pomace enrichment cultures as revealed by 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing. The relative abundances of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) representing bacteria are shown at the genus level. Rare groups representing <1% of total bacterial community were categorized as ‘Others’. OTUs representing the phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes could not be classified at the genus level. WPS-2, WWE1, vadinCA02 and HA73 represent uncultured bacterial groups. The full colour version of this figure is available at ISME Journal online.

Growth of Dhgm coupled with VC-to-ethene reductive dechlorination

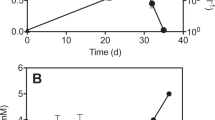

In solid-free enrichment cultures, VC dechlorination to ethene commenced after a lag phase of about 20 days and stoichiometric amounts of ethene were produced over a 50-day incubation period (Figure 2). qPCR results demonstrated that the Dhgm 16S rRNA gene copies per mL increased from 1.02±0.12 × 107 (cells transferred with the inoculum) to 3.76±0.14 × 108 (a 37-fold increase) following complete VC degradation. The growth yields of the Dhgm population in culture GP were in the range reported for VC-dechlorinating Dhc strains and up to 2 orders of magnitude higher than those reported for Dhgm lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 grown with chlorinated propanes (Supplementary Table 2). Following seven repeated transfers to fresh medium with VC as electron acceptor, culture GP maintained the ability to dechlorinate TCE, 1,1-DCE and cDCE to ethene (Supplementary Figure 4), and 1.66±0.44 × 109, 7.21±0.45 × 108 and 1.72±0.01 × 109 cells per μmole chlorinated electron acceptor consumed were produced. The VC-enriched culture GP lost the ability to dechlorinate PCE, and other potential chlorinated electron acceptors including CT, 1,2-DCA, 1,2,3-TCP and 1,2-DCP were not dechlorinated (data not shown).

VC-to-ethene reductive dechlorination in the enrichment culture harboring strain GP (triangles, VC; squares, methane; open circles, ethene; solid bar, Dhgm 16S rRNA gene copies). Data points are averages of duplicate cultures and the error bars show one standard deviation. If no error bars are shown, the standard deviations were too small to be illustrated.

Metagenome analyses

A comparative analysis of taxonomic ranks derived from the metagenomic sequences of culture GP, the Dhc-containing consortia ANAS, KB-1, Donna II and two non-dechlorinating microbial communities revealed that the metagenomes from dechlorinating and non-dechlorinating cultures did not produce distinct clusters (Figure 3a). Instead, the metagenomes were dispersed and the first principal component explained more than three times the variation observed between communities containing dechlorinating and non-dechlorinating members than principal component two (Figure 3a). The separation between samples observed along the first principal component axis can be attributed to differences in the relative abundances of taxonomic ranks representing the phyla Chloroflexi, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria and Cyanobacteria among metagenomes containing dechlorinating and non-dechlorinating taxa (Supplementary Table 3). For example, the average relative abundance of sequence reads representing Proteobacteria within non-dechlorinating metagenomes was 37.4±9.90%, but were lower (13.6±4.90%) in the metagenomes of the dechlorinating consortia. Sequences derived from members of the Chloroflexi had higher relative abundances in dechlorinating communities, whereas sequences representing the phyla Actinobacteria and Cyanobacteria had higher average relative abundances in metagenomes derived from the non-dechlorinating communities (Supplementary Table 3). In contrast, an ordination of the relative abundances of functional categories detected in the metagenomes indicated that the dechlorinating communities were more similar to each other than to the non-dechlorinating communities (Figure 3b). Specifically, the relative abundance of sequences assigned to branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis (0.17±0.05% in dechlorinating versus 0.06±0.02% in non-dechlorinating metagenomes), formate metabolism (0.11±0.01 versus 0.00%), iron transport (0.15±0.04 versus 0.02±0.03%), and reductive dechlorination (0.76±0.44 versus 0.00%) were enriched in the metagenomes of dechlorinating consortia (Supplementary Table 4). Further efforts to characterize the VC-dechlorinating culture GP relied on assigning genes from the assembled metagenome to the SEED (www.theseed.org) functional groups. More than 50% of the coding sequences from assembled contigs could not be assigned to a SEED functional category, indicating the presence of many genes with unknown functions in the VC-dechlorinating mixed culture GP. Among assigned SEED functional categories, genes encoding the metabolism of carbohydrates, amino acids and derivatives, proteins, DNA and cofactors/vitamins/prosthetic groups/pigments were highly represented in the assembled reads (Supplementary Table 5).

Principal component analysis of taxonomic profiles at the phylum level (a) and functional profiles (b) of metagenomes from the dechlorinating consortia ANAS, Donna ll, KB-1 and GP. Included in the analysis were the metagenome data sets from two non-dechlorinating microbial communities (AMD and Antarctica). For the functional comparison (b), the metagenomic sequences were classified into SEED categories and the distribution of SEED categories was compared. The full colour version of this figure is available at ISME Journal online.

Draft genome of the VC-dechlorinating Dhgm population

Binning of the metagenome sequences allowed the assembly of 16 contigs ranging in size between 1.0 kbp and 666.8 kbp (N50=277.2 kbp), and a draft genome of the organohalide-respiring Dhgm population was obtained. The draft genome had a size of 2.02 Mbp with a G+C content of 52%. CheckM analysis indicated that the genome was 94% complete (144 single copy marker genes detected) with 0% contamination and no strain heterogeneity (default 90% amino acid identity cutoff). Average contig coverage ranged between 7.5 and 505-fold, with an average genome coverage of 276-fold. Prokka annotation of the genomic bin predicted a total of 2099 genes including three ribosomal RNAs (5S, 16S and 23S rRNA), 2036 coding DNA sequences (CDS), 14 non-coding RNA sequences and 46 transfer RNAs. Pairwise sequence comparisons demonstrated that the 16S rRNA gene sequence representing the Dhgm sp. strain GP shares 99.3%, 96.9%, 96.0% and 95.3% sequence identities with Dhgm formicexedens strain NSZ-14 (Key et al., 2017), Dhgm alkenigignens strain IP3-3 (Key et al., 2016), Dhgm sp. strain WBC-2 (Molenda et al., 2016), and Dhgm lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 (Moe et al., 2009), respectively. Phylogenetic analysis based on concatenated 5S-16S-23S rRNA gene alignments supported Dhgm sp. strain GP’s affiliation with the Dhgm genus (Figure 4). A total of 2021 orthologous gene clusters were shared between the genomes of Dhgm strains NSZ-14, IP3-3, WBC-2, BL-DC-9 and GP and the genome of Dhc strain 195, and 1,921 gene orthologous clusters were shared by at least two genomes. Dhgm sp. strain GP shared 1454, 1294, 1159, 1047 and 915 orthologous clusters with Dhgm strains NSZ-14, IP3-3, WBC-2, BL-DC-9 and Dhc strain 195, respectively (Supplementary Figure 5). Although Dhgm sp. strain GP shares 99.3% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity with strain NSZ-14, the genome-aggregate average nucleotide identity (ANI) between both organisms is only 80.59%, well below the 95% ANI that corresponds to the 70% DNA–DNA hybridization standard that is frequently used for species demarcation (enve-omics.ce.gatech.edu; Löffler et al., 2013b), suggesting strain GP represents a distinct species.

Midpoint rooted maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree showing the relationship of ‘Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans’ to other members of the Chloroflexi based on concatenated 5S-16S-23S rRNA genes. The closest relatives of ‘Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans’ were Dhgm formicexedens strain NST-14T and Dhgm alkenigignens strain IP3-3. The accession numbers for each genome are listed in Supplementary Table 8. The scale bar indicates 0.01 nucleotide substitution per site.

A characteristic feature of obligate organohalide-respiring bacteria is the presence of multiple hydrogenase genes. Gene clusters encoding a [Ni/Fe] hydrogenase complex (EC 1.12.2.1), a NAD-reducing hydrogenase complex (EC 1.12.1.2), a periplasmic [Fe] hydrogenase complex (EC 1.12.7.2) and an uptake hydrogenase complex (EC 1.12.99.6) were identified on the draft genome. Similar to the other three sequenced Dhgm genomes (that is, strains BL-DC-9, IP3-3 and NSZ-14), which possess multiple genes annotated as formate dehydrogenase alpha subunit (Fdh), two genes encoding Fdh (EC 1.2.1.2) were identified on the genome of strain GP, whereas Dhc genomes harbor only one copy of the fdh gene. The phylogenetic analysis of putative Dhgm and Dhc Fdh proteins suggested that Dhgm may possess two types: one related to the Dhc-type Fdh (53.3% amino acid identity), while the other is more similar to Clostridium Fdh proteins (up to 48.7% identity) (Supplementary Figure 6). The Dhc-type Fdh has cysteine at the putative active site, while Dhgm-type Fdh has different amino acids (for example, cysteine or selenocysteine) at the same site (Supplementary Figure 7). A total of 52 putative RDase genes were identified, 10 of which were associated with B genes that encode B proteins with 1 to 4 transmembrane spanning helices (Supplementary Table 6). All putative RDase protein sequences had either a TAT signal peptide or a Sec signal peptide predicted by PRED-TAT (Supplementary Table 6) (Bagos et al., 2010). One of the predicted RDases (prokka_01475) shared 36.8%, 67.6% and 65.8% identities with the three characterized PcbA RDases identified in Dhc strains CG1, CG4 and CG5, respectively (Wang et al., 2014).

Although genes encoding c-type cytochromes were not found, two c-type cytochrome biogenesis genes, ccsA and ccsB (Hamel et al., 2003), were present in the strain GP draft genome. Both c-type cytochrome biogenesis genes were also present in other sequenced Dhgm and Dhc genomes but their functions remain unclear. Genes for de novo corrin ring biosynthesis were absent, but genes implicated in corrinoid salvage and modification (that is, cobA, cbiP, cbiB, cobU, cobT, cobC, cobS and cbiZ) were detected. Similar to observations made with Dhc, the Dhgm genome possesses genes encoding two distinct cobinamide (Cbi-)-salvaging pathways: the bacterial pathway relying on cobU/cobP genes and the archaeal cbiZ pathway. Genes coding for the vitamin B12 ABC transporter BtuFCD and the dual-function cobalt/nickel transporter system cbiMNQO were also identified.

The function of a putative heterodisulfide reductase gene cluster (hdrABC) in the genome of Dhgm strain GP is unclear but may be involved in electron bifurcation systems (for example, HdrABC-MvhADG of Methanothermobacter marburgensis, HdrABC-FlxABCD of Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough). In the electron bifurcation system of Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough, the HdrABC complex is responsible for transferring electrons (released from hydrogen or NADH+H+ oxidation catalyzed by the FlxABCD complex) to oxidized ferredoxin and a second electron acceptor small protein (for example, DsrC) (Ramos et al., 2015). While orthologs of genes encoding HdrABC were observed across all available Dhgm genomes, none were detected in any sequenced Dhc genome, suggesting Dhgm and Dhc may employ different electron transfer systems. It is also worth mentioning that the Dhgm draft genome harbors two genes in a single operon, which encode proteins sharing greater than 39 and 54% amino acid identity to arsD and arc3 of Escherichia coli, suggesting Dhgm strain GP experienced arsenic selection pressure and is capable of detoxifying arsenicals.

Protein profiling and identification of a novel putative VC RDase

Dhgm strain GP grew with VC as electron acceptor, but qPCR assays failed to detect the known VC RDase genes tceA, vcrA and bvcA, suggesting strain GP harbors a different (novel) VC RDase. The proteomics analysis identified three abundant putative RDases, prokka_00862, prokka_01300, and prokka_02004, in GP cultures grown with TCE, 1,1-DCE and VC, respectively (Figure 5; Supplementary Table 7). In cDCE-grown cultures, prokka_00862 and prokka_02004 had similar measured abundances (that is, normalized spectral counts), suggesting equal expression. The abundances of the detected peptides indicated high expression of the prokka_02004 RDase in cells collected from VC-grown GP cultures, while a lower abundance of the prokka_02004 RDase was observed in TCE-, 1,1-DCE-, cDCE-grown GP cultures (Supplementary Table 7). The prokka_02004 abundance correlated with the amount of ethene formed in the cultivation vessels amended with different chlorinated ethenes, supporting the proposition that prokka_02004 has activity towards VC. Prokka_02004 grouped in a cluster comprising the characterized RDases TceA, BvcA and VcrA (Figure 6), and shared 83.3, 56.1 and 49% amino acid similarity (76.2, 42.1 and 34.9% amino acid identity) with the TceA, and the characterized VC RDases BvcA and VcrA, respectively. No peptides representing RDase B proteins encoded in the genome of Dhgm strain GP were detected. Based on observations from both the phylogenetic (Figure 6) and proteomics analysis (Figure 5, Supplementary Table 7), the prokka_02004 RDase likely encodes a VC RDase and was designated cerA (that is, chloroethene reductase gene). Further examination of additional proteins detected in the Dhgm strain GP during active dechlorination of different chlorinated ethenes revealed an abundance of chaperonin proteins (GroES, GroEL and Hsp20) (Supplementary Table 7). High levels of rubrerythrin, thioredoxin and two proteins annotated as formate dehydrogenases (prokka_01480 and prokka_01481) were also observed.

Phylogenetic relationships of 528 RDase A protein sequences. The analysis included 355 sequences reported by Hug et al. (Hug and Edwards, 2013) plus the RDase sequences of Dhc strains CG1, CG4, CG5, SG1, and Dhgm strains WBC-2 and GP (Supplementary Information). Shaded in green and blue are clusters comprising known PCB and VC RDases, respectively. Putative RDases of strain GP are shown in red font and the stars highlight RDases prokka_02004 (blue), prokka_01300 (black), prokka_01297 (green) and prokka_00862 (red). The scale bar indicates 0.5 amino acid substitution per site. The full colour version of this figure is available at ISME Journal online.

Detection and abundance of Dhgm at sites impacted with chlorinated solvents

For contaminated site assessment, monitoring, and remediation treatment decision making, the quantitative measurement of Dhc biomarker genes has become routine practice. In 1173 groundwater samples collected from 111 chlorinated solvent-impacted sites, 16S rRNA genes of both Dhc and Dhgm, Dhc only and Dhgm only were detected in 849, 79 and 97 samples, respectively. In 148 samples (<13%), neither Dhgm nor Dhc 16S rRNA genes were detected. In 812 samples with quantifiable Dhgm and Dhc cell numbers, Dhgm outnumbered Dhc in the majority (65%) of samples and the Dhgm/Dhc ratio was above 1 in 524 samples (Figure 7). These findings indicate that Dhgm populations contribute more to the reductive dechlorination process in contaminated aquifers than has been previously acknowledged.

Distribution of Dhgm and Dhc in 1173 groundwater samples collected from 111 chlorinated solvent-impacted sites. Boxes represent the upper (75th) and lower (25th) quartiles and whiskers depict the non-outlier range. Outliers have Dhgm/Dhc ratios greater than the upper quartile Dhgm/Dhc ratio plus 1.5 times the difference between upper and lower quartile Dhgm/Dhc ratios, or less than the lower quartile Dhgm/Dhc ratio minus 1.5 times the difference between upper and lower quartile Dhgm/Dhc ratios. Dhgm/Dhc ratios greater than the upper quartile plus 2 times the difference of the quartiles or less than the lower quartile minus 2 times the difference between the quartiles were defined as extremes. Box plots were created using Statistica v12.0 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). The full colour version of this figure is available at ISME Journal online.

Description of ‘Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans’

‘Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans’ (e.the.ni.for’mans. N.L. n. ethenum, ethene; L. part. adj. formans forming; N.L. part. adj. etheniformans ethene forming). The species designation reflects the organism’s ability to form ethene from chlorinated ethenes. ‘Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans’ utilizes TCE, cDCE, 1,1-DCE and VC as respiratory electron acceptors. ‘Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans’ can be cultivated in mixed culture using hydrogen as electron donor, and acetate and/or lactate as carbon sources in bicarbonate-buffered medium. Growth occurs at 20–30 °C and circumneutral pH. The G+C content of strain GP is 52 mol%. Strain GP was identified in a mixed culture derived from non-contaminated grape pomace compost collected from the wine-growing region of Rotenberg near Stuttgart, Germany (48° 46' 58.0" N 9° 17' 14.8" E). Phylogenetic, genotypic and phenotypic characteristics place strain GP in the Dhgm genus within the organohalide-respiring Chloroflexi, and we propose that strain GP represents a new species, ‘Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans’.

Discussion

Among the organohalide-respiring Chloroflexi, Dhc have received most attention because of their ability to detoxify priority pollutants (He et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2014), their demonstrated relevance for in situ bioremediation (Löffler and Edwards, 2006; Stroo et al., 2012), and the availability of representative isolates (Maymó-Gatell et al., 1997; Adrian et al., 2000; He et al., 2003) and bioaugmentation consortia (Löffler et al., 2013a; Adrian and Löffler, 2016). To date, metabolic VC-to-ethene reductive dechlorination has been exclusively linked to the presence and activity of Dhc strains, and the value of monitoring Dhc 16S rRNA genes and the Dhc RDase genes tceA, vcrA and bvcA for supporting contaminated site management decisions has been demonstrated (Stroo et al., 2012). At sites, where VC disappearance was observed but Dhc were not detected, VC degradation was attributed to other processes, including abiotic reactions mediated by mineral phases such as magnetite (He et al., 2015) or aerobic microbial VC oxidation (Coleman et al., 2002; Mattes et al., 2010). The discovery of non-Dhc populations carrying novel VC RDase genes indicates that a broader diversity of microorganisms contributes to anaerobic VC metabolism and detoxification. This relevant observation demonstrates that the absence of known Dhc biomarker genes should not be used as an argument that the microbial reductive dechlorination process is not driving contaminant removal. A survey of 1173 groundwater wells from chlorinated solvent-impacted sites demonstrated that Dhgm were similarly distributed as Dhc, and in fact outnumbered Dhc in the majority of the wells where both Dhc and Dhgm were detected. Considering that a number of these samples were influenced by bioaugmentation with Dhc- (but not Dhgm-) containing consortia, Dhgm likely outnumber Dhc in even more of the sampling locations prior to bioremediation treatment. The known Dhgm genomes indicate a strict organohalide-respiring energy metabolism, and it is very likely that the presence of Dhgm implies that these bacteria contribute to in situ reductive dechlorination. Thus, the contribution of this organismal group to attenuation of chlorinated solvent contaminants is probably far greater than is currently appreciated.

Enrichment efforts with chlorinated ethenes from contaminated aquifer materials generally yield Dhc- rather than Dhgm-containing cultures. A possible reason is the slower growth of Dhgm (Supplementary Table 2) and Dhc may outcompete Dhgm strains in laboratory enrichment cultures. Very likely, refined growth conditions (for example, medium composition) will better meet the nutritional requirements of chlorinated ethene-dechlorinating Dhgm, an issue that has also limited the initial experimental efforts with Dhc cultures (Löffler et al., 2013b). For example, it was recently demonstrated that the lower base of the essential RDase corrinoid prosthetic group can affect reductive dechlorination rates and products (Yan et al., 2016), and the exact cobamide requirement to support efficient CerA maturation and catalytic activity has yet to be elucidated.

The majority of Dhc and Dhgm isolates and mixed cultures were derived from contaminated environments, with the exception of Dhc strain FL2, which was isolated from river sediment without reported chlorinated solvent exposure (He et al., 2005). Culture GP containing the first member of the Dhgm genus capable of using vinyl chloride as respiratory electron acceptor was obtained from grape pomace compost that had no prior exposure to chlorinated solvents. An earlier study found several Dehalococcoidia-type 16S rRNA gene sequences associated with a fluidized bed reactor digesting wine distillation waste (Godon et al., 1997), suggesting that organohalide-respiring Chloroflexi are members of the microbiome associated with processed grapes. This raises the question as to why an organism whose energy metabolism hinges on the presence of certain organohalogens, including chlorinated ethenes, is found in grape pomace that has never encountered chlorinated solvents? A plausible explanation is the active production of organohalogens in soils including composts, which support organohalide-respiring Chloroflexi such as strain GP. An unprecedented number of 52 putative RDase genes were identified on strain GP’s genome, indicating a possible adaptation to the non-contaminated environment from where the culture was obtained. For survival in pristine environments, obligate organohalide-respiring bacteria must rely on naturally produced organohalogens, and very likely use a diversity of halogenated compounds to derive sufficient energy for cell maintenance and growth. Evidence is accumulating that chlorinated hydrocarbons, including priority pollutants such as VC, are produced naturally in many environments, including soils (Keppler et al., 2002; Gribble, 2010). This is an important observation suggesting that RDases that use priority pollutants (for example, VC) as substrates evolve in environments without anthropogenic chlorinated solvent contamination. A survey detected 16S rRNA gene fragments of Dhc-like Chloroflexi in nearly 90% of the investigated 116 soil samples collected from locations not impacted by anthropogenic chlorinated hydrocarbons (Krzmarzick et al., 2012). A 16S rRNA gene sequencing effort identified Dhgm sequences at 60 m depth in a perennially stratified, pristine Arctic lake with saline, anoxic bottom waters (Comeau et al., 2012). Dhgm 16S rRNA gene sequences were also discovered in the photic layer (0–25 m) and the near-bottom zone (1465–1515 m) of Lake Baikal, the world’s deepest and most voluminous lake (Kurilkina et al., 2016). Recent work identified Dehalococcoidia-type sequences in a permanently ice-coved lake in Antarctica, and the authors speculated that hydrogenotrophic reductive dehalogenation could fuel anaerobic methane oxidation (Saxton et al., 2016). Consistent with the hypothesis that organohalide-respiring bacteria evolved long before human activities released chlorinated chemicals into the environment, our findings provide additional support that pristine environments harbor specialized organohalide-respiring bacteria that use chlorinated hydrocarbons, including chlorinated ethenes, as electron acceptors. It is plausible that this bacterial respiration evolved in response to soil processes generating organohalogens, which could have started when soils first formed in the late Silurian to Early Devonian some 400 million years ago (Keppler et al., 2000, 2002; Fahimi et al., 2003). Quite possibly, the natural formation of organohalogens dates back even further in marine systems (Gribble, 2010).

Obligate organohalide-respiring Dhgm and Dhc characteristically encode multiple RDase genes on their genomes. For example, 19, 32, 36, 11, 19, 22 RDase genes were identified on the genomes of Dhc strains 195, CBDB1, VS, BAV1, Dhgm strain BL-DC-9 and strain WBC-2, respectively (Adrian and Löffler, 2016), suggesting that the utilization of a broader suite of organohalogens as electron acceptors is a common feature. Dhgm strain GP possesses 52 putative RDase genes and the RDases prokka_01300, prokka_01297, prokka_00862, and prokka_02004 (CerA) were expressed in cultures grown with chlorinated ethenes. Proteomics analysis revealed that prokka_01300 was highly expressed when culture GP was grown with 1,1-DCE, suggesting this RDase is involved in 1,1-DCE reductive dechlorination. The putative RDase prokka_01297 was detected in GP cultures grown with cDCE, 1,1-DCE and VC, albeit with significantly lower spectral counts than the major RDases. Previous studies revealed the expression of multiple RDases in organohalide-respiring Chloroflexi grown with polychlorinated benzenes as electron acceptors, a phenomenon that is currently not understood (Schiffmann et al., 2014; Pöritz et al., 2015). The putative RDase prokka_00862 was differentially expressed when culture GP was cultivated with TCE, 1,1-DCE, cDCE and VC (Figure 5). Phylogenetic analysis did not group prokka_00862 with the known VC RDases, but affiliated this protein with the putative RDase DGWBC_1144 identified in Dhgm sp. strain WBC-2 (Figure 6). Dhgm sp. strain WBC-2 is responsible for transforming trans-1,2-dichloroethene (tDCE) to VC in a mixed culture enriched with 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane (Molenda et al., 2016). During growth with tDCE, strain WBC-2 expressed four RDases (DGWBC_0411, DGWBC_1144, DGWBC_1574 and DGWBC_0279), and blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) analysis identified DGWBC_0411, designated TdrA, as the tDCE-to-VC RDase (Molenda et al., 2016). No specific activity could be assigned to DGWBC_1144 but strain GP expressed a related protein (prokka_00862), and these putative RDases may have functional roles in reductive dechlorination of chlorinated ethenes. Strain GP also possesses an RDase (prokka_01475) that shares more than 65% amino acid identity with the PCB RDases PcbA-CG4 and PcbA-CG5 of Dhc strains CG4 and CG5, respectively (Figure 6). Dhgm 16S rRNA gene sequences have been detected in PCB-dechlorinating enrichment cultures (Wang and He, 2013) and PCB-impacted marine sediment (Klaus et al., 2016), suggesting that prokka_01475 represents a potentially novel PCB RDase.

Characterization of Dhc genomes showed that the majority of RDase A genes encoding the catalytically active RDases are associated with RDase B genes encoding putative membrane-anchor proteins (for example, 32 out of 32, 8 of 11, and 29 of 38 putative RDase A genes possess accompanying B genes in Dhc strain CBDB1, strain 11a, and strain MB, respectively) (Kube et al., 2005; Low et al., 2015). By comparison, Dhgm lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 possesses 17 putative RDase A genes, of which only six were reported to have cognate RDase B genes (Siddaramappa et al., 2012). A similar observation was made for Dhgm strain WBC-2 and 20 out of 22 putative RDase A genes do not have accompanying B genes (Molenda et al., 2016). Of the 52 putative RDase genes identified on the genome of strain GP, 10 have an associated B gene. Of the three RDases expressed in VC-grown GP cultures, only CerA is encoded by an RDase A gene with an associated B gene (Supplementary Table 6). The only other expressed RDase A protein encoded by a gene with an adjacent B gene is prokka_01300, a putative 1,1-DCE RDase (Figure 5). The current understanding of organohalide respiration is that RDase B proteins with transmembrane-spanning domains anchor the RDase to the outside of the cytoplasmic membrane (Hug, 2016). The majority (that is, 48 out of 52) of RDase A genes identified on the strain GP genome encode TAT signal peptides indicative of protein transport through the cytoplasmic membrane (Supplementary Table 6). It is currently unclear if RDase A enzymes without accompanying RDase B protein are functional, or if a single RDase B protein can anchor distinct catalytic A units. Expression of RDase B proteins could not be confirmed in proteomic analysis, and it remains to be determined if RDase A genes not associated with an RDase B gene encode RDases functional in organohalide respiration. Interestingly, some RDases (prokka_00862 and prokka_01297) expressed by strain GP are predicted to possess a Sec signal peptide and transmembrane-spanning regions (Supplementary Table 6), suggesting that not all RDase A proteins may require B proteins for catalytic activity. Further investigations are required to derive mechanistic understanding of RDase A interactions with the cytoplasmic membrane.

In contrast to the characterized Dhgm isolates, Dhc strains cannot utilize formate, although genes encoding subunits of formate dehydrogenase have been annotated in Dhc genomes (Key et al., 2017). Due to the lack of the corresponding enzyme activity, the formate dehydrogenase annotation was recently modified to ‘complex iron-sulfur molybdoenzyme’ (CISM) (Kublik et al., 2016). In Dhc strain CBDB1, CISM forms a complex with the RDase and the iron-sulfur cluster containing subunit of the hydrogen uptake hydrogenase Hup. The complex is localized on the outer side of the cytoplasmic membrane and presumably mediates electron transfer from hydrogen to the chlorinated electron acceptor (Kublik et al., 2016). Interestingly, Dhgm possesses two different CISM gene clusters (prokka_00355 and prokka_01480) and Dhgm may possess two distinct electron transfer complexes. Dhgm also possesses the genes encoding heterodisulfide reductase, an electron bifurcation system and Dhgm may utilize HdrABC for electron splitting as part of the organohalide respiration process.

The comparative metagenome analysis of consortia ANAS, KB-1 and Donna ll, all capable of converting polychlorinated ethenes to ethene, revealed similar functional characteristics based on SEED functional categories, yet little resemblance was observed regarding the relative abundance of non-dechlorinating taxa within each consortium (Hug et al., 2012). Similar conclusions were derived from the culture GP metagenome analysis, indicating that functional, and not taxonomic, redundancy is the norm in reductively dechlorinating communities. This information may have value to predict the potential success of natural attenuation in environments impacted with chlorinated solvents, where metagenomics can reveal enriched functions. Therefore, additional metagenomes of dechlorinating consortia and environments impacted by chlorinated solvents can further refine the characteristic gene content of microbial communities performing organohalide respiration.

Unique features of dechlorinating culture GP included the persistence of 16S rRNA genes of the bacterial phylum WWE1 during the enrichment process. Phylum WWE1, which was recently proposed as candidate phylum Cloacimonetes (Rinke et al., 2013), was first identified in a municipal anaerobic sludge digester (Chouari et al., 2005). To date, no stable enrichment cultures or isolates representing this phylum have been obtained, likely due to their symbiotic relationships with hydrogenotrophic microorganisms (Chojnacka et al., 2015). Metagenome analysis of a municipal anaerobic sludge digester lead to the assembly of the genome of ‘Candidatus Cloacimonas acidaminovorans’, a member of phylum WWE1. Annotation of the genome suggested amino acid fermentation as the organism’s main metabolism (Pelletier et al., 2008). In meromictic Sakinaw Lake, the depth-dependent co-occurrence of Chloroflexi, Candidate divisions WWE1, OP9/JS1, OP8 and OD1, and methanogens suggested syntrophic interactions between these groups (Gies et al., 2014). The findings reported in several metagenomic studies support a coexistence pattern between Chloroflexi, candidate phylum WWE1 and methanogens (Wrighton et al., 2012; Hug et al., 2013a; Wrighton et al., 2014). Dechlorinating culture GP harbored Dhgm-type Chloroflexi, phylum WWE1 and hydrogenotrophic methanogens, and this community could be maintained in defined, bicarbonate-buffered medium amended with lactate and VC. Thus, culture GP is a potential source for isolating phylum WWE1 representatives.

Collectively, these results demonstrate that pristine (that is, not impacted by anthropogenic chlorinated solvents) habitats (for example, grape pomace compost) harbor organohalide-respiring bacteria. Thus microbiomes associated with pristine ecosystems can be a source of novel RDases such as the VC RDase CerA with potential value for biotechnological applications. The survey of 1173 groundwater samples demonstrated that Dhgm commonly occur in contaminated aquifers, and evidence that this bacterial group contributes to VC detoxification has implications for contaminated site assessment, monitoring, and decision making. The findings further emphasize that organohalide-respiring Dehalococcoidia participate in the natural cycling of chlorine and carbon, and highlight that organohalide respiration occurs in pristine environments. The latter observation has implications for energy-depleted and isolated environments where naturally occurring halogenated hydrocarbons could fuel microbial life.

References

Adrian L, Szewzyk U, Wecke J, Görisch H . (2000). Bacterial dehalorespiration with chlorinated benzenes. Nature 408: 580–583.

Adrian L, Löffler FE . (2016) Organohalide-Respiring Bacteria. Springer: Berlin Heidelberg.

Bagos PG, Nikolaou EP, Liakopoulos TD, Tsirigos KD . (2010). Combined prediction of Tat and Sec signal peptides with hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics 26: 2811–2817.

Cápiro NL, Wang Y, Hatt JK, Lebron CA, Pennell KD, Löffler FE . (2014). Distribution of organohalide-respiring bacteria between solid and aqueous phases. Environ Sci Technol 48: 10878–10887.

Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Lozupone CA, Turnbaugh PJ et al. (2011). Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 4516–4522.

Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Huntley J, Fierer N et al. (2012). Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J 6: 1621–1624.

Chojnacka A, Szczesny P, Blaszczyk MK, Zielenkiewicz U, Detman A, Salamon A et al. (2015). Noteworthy facts about a methane-producing microbial community processing acidic effluent from sugar beet molasses fermentation. PLoS One 10: e0128008.

Chouari R, Le Paslier D, Dauga C, Daegelen P, Weissenbach J, Sghir A . (2005). Novel major bacterial candidate division within a municipal anaerobic sludge digester. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 2145–2153.

Chourey K, Jansson J, VerBerkmoes N, Shah M, Chavarria KL, Tom LM et al. (2010). Direct cellular lysis/protein extraction protocol for soil metaproteomics. J Proteome Res 9: 6615–6622.

Chourey K, Nissen S, Vishnivetskaya T, Shah M, Pfiffner S, Hettich RL et al. (2013). Environmental proteomics reveals early microbial community responses to biostimulation at a uranium- and nitrate- contaminated site. Proteomics 13: 2921–2930.

Coleman NV, Mattes TE, Gossett JM, Spain JC . (2002). Phylogenetic and kinetic diversity of aerobic vinyl chloride-assimilating bacteria from contaminated sites. Appl Environ Microbiol 68: 6162–6171.

Comeau AM, Harding T, Galand PE, Vincent WF, Lovejoy C . (2012). Vertical distribution of microbial communities in a perennially stratified Arctic lake with saline, anoxic bottom waters. Sci Rep 2: 604.

Da Silva ML, Alvarez P . (2008). Exploring the correlation between halorespirer biomarker concentrations and TCE dechlorination rates. J Environ Eng 134: 895–901.

Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D . (2012). jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods 9: 772.

Fahimi IJ, Keppler F, Schöler HF . (2003). Formation of chloroacetic acids from soil, humic acid and phenolic moieties. Chemosphere 52: 513–520.

Gies EA, Konwar KM, Beatty JT, Hallam SJ . (2014). Illuminating microbial dark matter in meromictic Sakinaw Lake. Appl Environ Microbiol 80: 6807–6818.

Godon JJ, Zumstein E, Dabert P, Habouzit F, Moletta R . (1997). Molecular microbial diversity of an anaerobic digestor as determined by small-subunit rDNA sequence analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 63: 2802–2813.

Goldman SM, Quinlan PJ, Ross GW, Marras C, Meng C, Bhudhikanok GS et al. (2012). Solvent exposures and Parkinson disease risk in twins. Ann Neurol 71: 776–784.

Gribble GW . (2010) Naturally Occurring Organohalogen Compounds: a Comprehensive Update. Springer Science & Business Media: New York.

Hamel PP, Dreyfuss BW, Xie Z, Gabilly ST, Merchant S . (2003). Essential histidine and tryptophan residues in CcsA, a system II polytopic cytochrome c biogenesis protein. J Biol Chem 278: 2593–2603.

He J, Sung Y, Krajmalnik-Brown R, Ritalahti KM, Löffler FE . (2005). Isolation and characterization of Dehalococcoides sp. strain FL2, a trichloroethene (TCE)- and 1,2-dichloroethene-respiring anaerobe. Environ Microbiol 7: 1442–1450.

He J, Ritalahti KM, Yang KL, Koenigsberg SS, Löffler FE . (2003). Detoxification of vinyl chloride to ethene coupled to growth of an anaerobic bacterium. Nature 424: 62–65.

He YT, Wilson JT, Su C, Wilkin RT . (2015). Review of abiotic degradation of chlorinated solvents by reactive iron minerals in aquifers. Ground Water Monit Remediat 35: 57–75.

Hug LA, Beiko RG, Rowe AR, Richardson RE, Edwards EA . (2012). Comparative metagenomics of three Dehalococcoides-containing enrichment cultures: the role of the non-dechlorinating community. BMC Genomics 13: 327.

Hug LA, Castelle CJ, Wrighton KC, Thomas BC, Sharon I, Frischkorn KR et al. (2013a). Community genomic analyses constrain the distribution of metabolic traits across the Chloroflexi phylum and indicate roles in sediment carbon cycling. Microbiome 1: 22.

Hug LA, Edwards EA . (2013). Diversity of reductive dehalogenase genes from environmental samples and enrichment cultures identified with degenerate primer PCR screens. Front Microbiol 4: 341.

Hug LA, Maphosa F, Leys D, Löffler FE, Smidt H, Edwards EA et al. (2013b). Overview of organohalide-respiring bacteria and a proposal for a classification system for reductive dehalogenases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 368: 20120322.

Hug LA . (2016) Diversity, evolution, and environmental distribution of reductive dehalogenase genes. In: Adrian L, Löffler FE (eds) Organohalide-Respiring Bacteria. Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, pp 377–393.

Keppler F, Eiden R, Niedan V, Pracht J, Schöler HF . (2000). Halocarbons produced by natural oxidation processes during degradation of organic matter. Nature 403: 298–301.

Keppler F, Borchers R, Pracht J, Rheinberger S, Schöler HF . (2002). Natural formation of vinyl chloride in the terrestrial environment. Environ Sci Technol 36: 2479–2483.

Key TA, Richmond DP, Bowman KS, Cho YJ, Chun J, da Costa MS et al. (2016). Genome sequence of the organohalide-respiring Dehalogenimonas alkenigignens type strain IP3-3T Stand Genomic Sci 11: 44.

Key TA, Bowman KS, Lee I, Chun J, da Costa M, Albuquerque L et al. (2017). Dehalogenimonas formicexedens sp. nov., a chlorinated alkane respiring bacterium isolated from contaminated groundwater Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 67: 1366–1373.

Kielhorn J, Melber C, Wahnschaffe U, Aitio A, Mangelsdorf I . (2000). Vinyl chloride: still a cause for concern. Environ Health Perspect 108: 579–588.

Klaus J, Kourafalou V, Piggot A, Reniers A, Kang H, Kumar N et al. (2016). Potential impacts of PCBs on sediment microbiomes in a tropical marine environment. J Mar Sci Eng 4: 13.

Krzmarzick MJ, Crary BB, Harding JJ, Oyerinde OO, Leri AC, Myneni SC et al. (2012). Natural niche for organohalide-respiring Chloroflexi. Appl Environ Microbiol 78: 393–401.

Kube M, Beck A, Zinder SH, Kuhl H, Reinhardt R, Adrian L . (2005). Genome sequence of the chlorinated compound–respiring bacterium Dehalococcoides species strain CBDB1 Nat Biotechnol 23: 1269–1273.

Kublik A, Deobald D, Hartwig S, Schiffmann CL, Andrades A, Bergen M et al. (2016). Identification of a multi-protein reductive dehalogenase complex in Dehalococcoides mccartyi strain CBDB1 suggests a protein-dependent respiratory electron transport chain obviating quinone involvement Environ Microbiol 18: 3044–3056.

Kurilkina MI, Zakharova YR, Galachyants YP, Petrova DP, Bukin YS, Domysheva VM et al. (2016). Bacterial community composition in the water column of the deepest freshwater Lake Baikal as determined by next-generation sequencing. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 92: fiw094.

Laczny CC, Sternal T, Plugaru V, Gawron P, Atashpendar A, Margossian HH et al. (2015). VizBin-an application for reference-independent visualization and human-augmented binning of metagenomic data. Microbiome 3: 1.

Löffler FE, Sanford RA, Ritalahti KM . (2005). Enrichment, cultivation, and detection of reductively dechlorinating bacteria. Method Enzymol 397: 77–111.

Löffler FE, Edwards EA . (2006). Harnessing microbial activities for environmental cleanup. Curr Opin Biotechnol 17: 274–284.

Löffler FE, Ritalahti KM, Zinder SH . (2013a). Dehalococcoides and reductive dechlorination of chlorinated solvents. In: Stroo HF, Leeson A, Ward CH (eds). Bioaugmentation for Groundwater Remediation. Springer: New York, pp 39–88.

Löffler FE, Yan J, Ritalahti KM, Adrian L, Edwards EA, Konstantinidis KT et al. (2013b). Dehalococcoides mccartyi gen. nov., sp. nov., obligately organohalide-respiring anaerobic bacteria relevant to halogen cycling and bioremediation, belong to a novel bacterial class, Dehalococcoidia classis nov., order Dehalococcoidales ord. nov. and family Dehalococcoidaceae fam. nov., within the phylum Chloroflexi Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 63: 625–635.

Low A, Shen Z, Cheng D, Rogers MJ, Lee PK, He J . (2015). A comparative genomics and reductive dehalogenase gene transcription study of two chloroethene-respiring bacteria, Dehalococcoides mccartyi strains MB and 11a Sci Rep 5: 15204.

Lu X, Wilson JT, Kampbell DH . (2006). Relationship between Dehalococcoides DNA in ground water and rates of reductive dechlorination at field scale Water Res 40: 3131–3140.

Mattes TE, Alexander AK, Coleman NV . (2010). Aerobic biodegradation of the chloroethenes: pathways, enzymes, ecology, and evolution. FEMS Microbiol Rev 34: 445–475.

Maymó-Gatell X, Chien Y-t, Gossett JM, Zinder SH . (1997). Isolation of a bacterium that reductively dechlorinates tetrachloroethene to ethene. Science 276: 1568–1571.

McCarty PL . (2010) Groundwater contamination by chlorinated solvents: history, remediation technologies and strategies. In: Stroo HF, Ward CH (eds). In Situ Remediation of Chlorinated Solvent Plumes. Springer: New York, pp 1–28.

Moe WM, Yan J, Nobre MF, da Costa MS, Rainey FA . (2009). Dehalogenimonas lykanthroporepellens gen. nov., sp. nov., a reductively dehalogenating bacterium isolated from chlorinated solvent-contaminated groundwater Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 59: 2692–2697.

Molenda O, Quaile AT, Edwards EA . (2016). Dehalogenimonas sp. strain WBC-2 genome and identification of its trans-dichloroethene reductive dehalogenase, TdrA Appl Environ Microbiol 82: 40–50.

Oh S, Caro-Quintero A, Tsementzi D, DeLeon-Rodriguez N, Luo C, Poretsky R et al. (2011). Metagenomic insights into the evolution, function, and complexity of the planktonic microbial community of Lake Lanier, a temperate freshwater ecosystem. Appl Environ Microbiol 77: 6000–6011.

Overbeek R, Olson R, Pusch GD, Olsen GJ, Davis JJ, Disz T et al. (2014). The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res 42: D206–D214.

Parks DH, Tyson GW, Hugenholtz P, Beiko RG . (2014). STAMP: statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics 30: 3123–3124.

Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW . (2015). CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res 25: 1043–1055.

Pelletier E, Kreimeyer A, Bocs S, Rouy Z, Gyapay G, Chouari R et al. (2008). 'Candidatus Cloacamonas acidaminovorans': genome sequence reconstruction provides a first glimpse of a new bacterial division J Bacteriol 190: 2572–2579.

Pöritz M, Schiffmann CL, Hause G, Heinemann U, Seifert J, Jehmlich N et al. (2015). Dehalococcoides mccartyi strain DCMB5 respires a broad spectrum of chlorinated aromatic compounds Appl Environ Microbiol 81: 587–596.

Ramos AR, Grein F, Oliveira GP, Venceslau SS, Keller KL, Wall JD et al. (2015). The FlxABCD-HdrABC proteins correspond to a novel NADH dehydrogenase/heterodisulfide reductase widespread in anaerobic bacteria and involved in ethanol metabolism in Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough Environ Microbiol 17: 2288–2305.

Rinke C, Schwientek P, Sczyrba A, Ivanova NN, Anderson IJ, Cheng JF et al. (2013). Insights into the phylogeny and coding potential of microbial dark matter. Nature 499: 431–437.

Ritalahti KM, Amos BK, Sung Y, Wu Q, Koenigsberg SS, Löffler FE . (2006). Quantitative PCR targeting 16S rRNA and reductive dehalogenase genes simultaneously monitors multiple Dehalococcoides strains Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 2765–2774.

Ritalahti KM, Hatt JK, Lugmayr V, Henn K, Petrovskis EA, Ogles DM et al. (2010). Comparing on-site to off-site biomass collection for Dehalococcoides biomarker gene quantification to predict in situ chlorinated ethene detoxification potential Environ Sci Technol 44: 5127–5133.

Saxton MA, Samarkin VA, Schutte CA, Bowles MW, Madigan MT, Cadieux SB et al. (2016). Biogeochemical and 16S rRNA gene sequence evidence supports a novel mode of anaerobic methanotrophy in permanently ice-covered Lake Fryxell, Antarctica. Limnol Oceanogr 61: S119–S130.

Schiffmann CL, Jehmlich N, Otto W, Hansen R, Nielsen PH, Adrian L et al. (2014). Proteome profile and proteogenomics of the organohalide-respiring bacterium Dehalococcoides mccartyi strain CBDB1 grown on hexachlorobenzene as electron acceptor J Proteomics 98: 59–64.

Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB et al. (2009). Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 75: 7537–7541.

Siddaramappa S, Challacombe JF, Delano SF, Green LD, Daligault H, Bruce D et al. (2012). Complete genome sequence of Dehalogenimonas lykanthroporepellens type strain (BL-DC-9T and comparison to 'Dehalococcoides' strains Stand Genomic Sci 6: 251–264.

Stamatakis A . (2014). RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30: 1312–1313.

Stroo HF, Leeson A, Ward CH . (2012) Bioaugmentation for Groundwater Remediation, vol. 5. Springer: New York.

Strous M, Kraft B, Bisdorf R, Tegetmeyer HE . (2012). The binning of metagenomic contigs for microbial physiology of mixed cultures. Front Microbiol 3: 410.

Sung Y, Ritalahti KM, Apkarian RP, Löffler FE . (2006). Quantitative PCR confirms purity of strain GT, a novel trichloroethene-to-ethene-respiring Dehalococcoides isolate Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 1980–1987.

Tavaré S . (1986). Some probabilistic and statistical problems in the analysis of DNA sequences. Lectures Math Life Sci 17: 57–86.

Wang S, He J . (2013). Phylogenetically distinct bacteria involve extensive dechlorination of aroclor 1260 in sediment-free cultures. PLoS One 8: e59178.

Wang S, Chng KR, Wilm A, Zhao S, Yang KL, Nagarajan N et al. (2014). Genomic characterization of three unique Dehalococcoides that respire on persistent polychlorinated biphenyls Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 12103–12108.

Wartenberg D, Reyner D, Scott CS . (2000). Trichloroethylene and cancer: epidemiologic evidence. Environ Health Perspect 108: 161–176.

Wrighton KC, Thomas BC, Sharon I, Miller CS, Castelle CJ, VerBerkmoes NC et al. (2012). Fermentation, hydrogen, and sulfur metabolism in multiple uncultivated bacterial phyla. Science 337: 1661–1665.

Wrighton KC, Castelle CJ, Wilkins MJ, Hug LA, Sharon I, Thomas BC et al. (2014). Metabolic interdependencies between phylogenetically novel fermenters and respiratory organisms in an unconfined aquifer. ISME J 8: 1452–1463.

Yan J, Rash BA, Rainey FA, Moe WM . (2009). Detection and quantification of Dehalogenimonas and 'Dehalococcoides' populations via PCR-based protocols targeting 16S rRNA genes Appl Environ Microbiol 75: 7560–7564.

Yan J, Simsir B, Farmer AT, Bi M, Yang Y, Campagna SR et al. (2016). The corrinoid cofactor of reductive dehalogenases affects dechlorination rates and extents in organohalide-respiring Dehalococcoides mccartyi ISME J 10: 1092–1101.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP project ER-2312) and by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Superfund Research Program under the (R01ES24294). We thank Heinz Munder, Mundifruit Wine Union, Stuttgart, Germany for helpful discussions. We thank Microbial Insights for providing the qPCR data performed on the groundwater samples on a commercial basis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Higgins, S., Yan, J. et al. Grape pomace compost harbors organohalide-respiring Dehalogenimonas species with novel reductive dehalogenase genes. ISME J 11, 2767–2780 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.127

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.127

This article is cited by

-

Global prevalence of organohalide-respiring bacteria dechlorinating polychlorinated biphenyls in sewage sludge

Microbiome (2024)

-

Effect of wine pomace extract on dechlorination of chloroethenes in soil suspension

Bioresources and Bioprocessing (2023)

-

Mimicking reductive dehalogenases for efficient electrocatalytic water dechlorination

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Diversity of organohalide respiring bacteria and reductive dehalogenases that detoxify polybrominated diphenyl ethers in E-waste recycling sites

The ISME Journal (2022)

-

Integration of microbial reductive dehalogenation with persulfate activation and oxidation (Bio-RD-PAO) for complete attenuation of organohalides

Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering (2022)