Abstract

Bacterioplankton respiration (BR) may represent the largest single sink of organic carbon in the biosphere and constitutes an important driver of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from freshwaters. Complete understanding of BR is precluded by the fact that most studies need to assume a respiratory quotient (RQ; mole of CO2 produced per mole of O2 consumed) to calculate rates of BR. Many studies have, without clear support, assumed a fixed RQ around 1. Here we present 72 direct measurements of bacterioplankton RQ that we carried out in epilimnetic samples of 52 freshwater sites in Québec (Canada), using O2 and CO2 optic sensors. The RQs tended to converge around 1.2, but showed large variability (s.d.=0.45) and significant correlations with major gradients of ecosystem-level, substrate-level and bacterial community-level characteristics. Experiments with natural bacterioplankton using different single substrates suggested that RQ is intimately linked to the elemental composition of the respired compounds. RQs were on average low in net autotrophic systems, where bacteria likely were utilizing mainly reduced substrates, whereas we found evidence that the dominance of highly oxidized substrates, for example, organic acids formed by photo-chemical processes, led to high RQ in the more heterotrophic systems. Further, we suggest that BR contributes to a substantially larger share of freshwater CO2 emissions than presently believed based on the assumption that RQ is ∼1. Our study demonstrates that bacterioplankton RQ is not only a practical aspect of BR determination, but also a major ecosystem state variable that provides unique information about aquatic ecosystem functioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bacterioplankton respiration (BR) in oceanic and inland water systems may represent the largest single sink of organic carbon (C) in the biosphere (del Giorgio and Williams, 2005a). Inland waters are often supersaturated in carbon dioxide (CO2) (del Giorgio et al., 1997; Prairie et al., 2002) and, although covering only 1% of the earth's surface, they seemingly emit CO2 to the atmosphere at a rate that is of a similar order of magnitude as that of fossil fuel combustion or C uptake by oceans (Battin et al., 2009; Tranvik et al., 2009). Some of these CO2 emissions originate from BR fueled by terrestrially derived organic C (Karlsson et al., 2007; McCallister and del Giorgio, 2008). However, uncertainties in the quantitative importance of BR, by itself and relative to other processes that also generate aquatic CO2 (Granéli et al., 1996; Humborg et al., 2010), still precludes a complete understanding of BR and overall aquatic carbon cycling.

One seldom addressed uncertainty that is central to the process of BR is the bacterial respiratory quotient (RQ). Most studies of aquatic bacterial metabolism have inferred BR from O2 consumption rates, measured using traditional chemical approaches (Winkler, 1888) or modern spectrometric (del Giorgio et al., 2011), electrode and optode (Marchand et al., 2009) techniques. At a resolution several-fold higher than that for CO2, the O2 techniques have expanded the possibilities to measure BR in many types of aquatic systems, however, at the cost of needing to apply a RQ (moles produced CO2 per mole consumed O2) to derive the rates of CO2 production.

Although the bacterioplankton RQ has profound conceptual importance and significant practical implications, few empirical determinations exist. There have been a handful of studies of marine RQ (Oviatt et al., 1986; Robinson et al., 2002), but to our knowledge, only one study targeting the RQ of natural freshwater bacterioplankton (Cimbleris and Kalff, 1998). Because of the lack of data on either the magnitude or the patterns of variability in ambient bacterial RQs, studies to date have applied fixed RQs in the range of 0.7–1.2 based on more or less arbitrary assumptions.

A common theoretical way to assess RQ is to analyze the stoichiometry of complete oxidation of different substrates (Table 1). In glucose respiration, 6O2 is required for transformation of C6H12O6 into 6H2O and 6CO2 at the RQ of exactly 1 CO2/O2. Oxidation of average phytoplanktonic material (sensu Takahashi et al., 1985; Anderson, 1995; Hedges et al., 2002) implies a low theoretical RQ of 0.7, as plankton are constituted by reduced and oxygen-poor components such as lipids and proteins. Humic-rich colored dissolved organic carbon (DOC) of terrestrial origin, which globally dominates freshwater bacterial substrates (del Giorgio et al., 1997; Jansson et al., 2007; Karlsson et al., 2009), is completely oxidized at an RQ of ca 0.9 (Dilly, 2001). However, recent studies show that bacteria selectively utilize sub-pools of the bulk DOC (Berggren et al., 2007; Guillemette and del Giorgio, 2011). Small organic acids that contribute to high RQ are preferentially metabolized (Berggren et al., 2010) and through photo-transformation of humic substances, organic acids with theoretical RQ above 1 are systematically formed and may have a key role for bacterial metabolism (Kieber et al., 1989; Bertilsson and Tranvik, 1998; Pullin et al., 2004).

The RQ is also theoretically regulated by biochemical pathways of metabolism. For example, instead of being completely oxidized, glucose may be used for growth or enzyme production according to chemical equations (Herbert, 1976) that correspond to an RQ of ∼1.2. Hypothetically, the bacterial RQ could be particularly affected by enzymatic production in humic systems, where exoenzymes have a major role in the depolymerization of large humic molecules and in the release of their contents of phosphorus (Münster et al., 1992; Middelboe and Søndergaard, 1993).

Thus, natural bacterioplankton utilize complex substrate mixtures, and the cells themselves have a wide range of physiological states. It could be expected that the resulting community-level RQs is not constant, but vary across freshwater gradients to reflect the dominant pools of organic C (algal, terrestrial, photochemically derived) respired by bacterioplankton and the factors that influence bacterial activity. Quantifying this variability in RQ is not only important to improve freshwaters BR estimation: the patterns in RQ will, in turn, inform on fundamental shifts in bacterial physiology and C consumption that may occur along the environmental gradients, and that are not evident from any other measurement.

We here present the first systematic, large-scale study of bacterioplankton community RQ carried out in freshwaters. We explore the variation in RQ in 52 different lakes, ponds and tarns in Québec (Canada), spanning wide ranges in water chemical characteristics, productivity and degree of terrestrial influence. We measured the RQ non-invasingly during relatively short incubations at dark in situ conditions. It was hypothesized that the RQ is <1 in net autotrophic systems, where phytoplanktonic carbon sources are likely to dominate the bacterial metabolism, but >1 in other systems where photochemically produced organic acids may have a larger role.

Materials and methods

Sites

A total of 52 sites in Québec, Canada, were sampled from mid July to mid August, 2010 (Supplementary Table S1). A subset of 17 sites were sampled again in early October and additional sampling was carried out occasionally at Lakes Croche and Hébécourt. The sites (0.01–511 km2) were situated in the clay belt of western Québec (n=29), in the wetland-dominated area south of James Bay (n=13), and in the Laurentian shield in south–eastern Québec (n=10). Many of the waters were shallow, sometimes dammed by beavers, and often brown, turbid and macrophyte rich. In this paper, we refer to all small water bodies (<1 km2) with a depth at the center of <2 m as ‘shallow ponds and tarns’ (n=17; one 2.2 km2 site of 0.9 m depth was also included). The remaining sites are defined as ‘lakes’ (n=35). See Supplementary Table S1 for site characteristics and coordinates.

Sampling and in situ analyses

Lakes with road access were sampled by boat, but over 1/3 of the lakes had to be sampled from a hydroplane. Water was collected at the center of each lake, at 0.5 m depth, in 18 l cubitainers using a peristaltic pump. Shallow ponds and tarns with areas >0.10 km2 were sampled as lakes, whereas those with <0.10 km2 were sampled a few meter from the shore using a pole sampler.

Ambient dissolved O2, water temperature, pH and depth were measured in situ with a combination probe (YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH, USA). In situ pCO2 was measured using an EGM-4 infrared gas analyzer (PP Systems, Amesbury, MA, USA) receiving air, equilibrated with the water by pumping (100 l h−1) through a Liqui-Cel MiniModule (Membrana, Charlotte, NC, USA). In some smaller ponds, pCO2 was measured using a headspace equilibration method. A 60-ml syringe was filled with sample water and ambient air (in equal proportions), sealed and shaken, following direct injection of the headspace gas into the EGM-4. Sample pCO2 was calculated to take into account for CO2 movements between the water and gas phase during equilibration. CO2 fluxes at the water–air interface were measured daytime using a floating chamber (diameter 38 cm, above water volume 17 l) connected to an EGM-4. Readings of CO2 concentration in the chamber headspace were taken each minute for duplicate periods of 10 min. Day-time flux measurements from these floating chambers are overestimating daily fluxes because of induced water turbulence (Vachon et al., 2010), implying that a calculated contribution (%) to the measured CO2 efflux by BR becomes conservative.

In vitro analyses

Water from each site was gently filtered through ‘A/E Glass’ filters (PALL Life Sciences, Port Washington, NY, USA; 142-mm diameter, 1.0-μm pore size). This filtration separated bacterioplankton from most other planktonic components (del Giorgio and Pace, 2008). Bacterial O2 consumption was measured on the filtrate with a ‘Fibox 3′ system (PreSens, Regensburg, Germany) as described by Marchand et al. (2009). Within 2–6 h from sampling, duplicate 500 ml Erlenmeyer flasks, equipped with O2 optodes, were filled for each sample, sealed with silicone stoppers and incubated at ambient epilimnetic temperatures using dark circulating water baths. The incubations were allowed to stabilize for ca 1 h before the first sensor reading was performed in a series of daily measurements (1–3 times per day). The protocol allowed for repeated non-invasive readings of each optode from the outside of the closed flasks (Marchand et al., 2009). The CO2 production was measured in the same incubation flasks using a ‘pCO2 mini’ optode system (PreSens). Every time an O2 sensor was read with the Fibox 3, a parallel CO2 sensor (attached 3 cm from the O2 optode) was read with the pCO2 mini. Each incubation was stopped when all sensors (duplicates of O2 and CO2 optodes) had recorded significant rates of O2 consumption and CO2 production (one-tail test of significance of the O2-time and CO2-time correlations, α=0.05). The O2 concentration during the incubations never dropped to levels that are known to slow down bacterioplankton process rates (<2 mg l−1).

We used O2 optodes that had recently been calibrated by the manufacturer. The CO2 optodes were calibrated at our laboratory. Ten out of 42 sensors were selected for a 9-point calibration. A series of CO2 dilutions was prepared, with pCO2 (measured with EGM-4 using the headspace equilibration method) from 200 to 20 000 p.p.m.v. The CO2 optodes were equilibrated with each dilution for 2 h before measurement. Using the pCO2 mini software, a four-parameter logistic calibration curve was generated (Supplementary Figure S1).

Single-substrate experiments

Single-carbon substrate (4 mg l−1 of DOC) solutions of tryptophan, glucose, citric acid, tartaric and oxalic acid were prepared in Nanopure water. Inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus (0.5 mg of nitrogen per litre in the form of NH4NO3 and 50 μg of phosphorus per litre in the form of KH2PO4) were added to all substrate solutions, which were then inoculated (10% inoculum of final volume) with freshly sampled water from one of the study sites (oligotrophic lake Croche; see Supplementary Table S1). The inoculum, which had been pre-filtered through PALL A/E Glass filters (see above), was assumed to contain sufficient concentrations of essential micronutrients. Incubations in 500 ml Erlenmeyer flasks equipped with O2 and CO2 optodes were then carried out in the same way as described above, but at a fixed temperature of 20 °C and with incubation times proceeding until a stationary phase had been reached. As blank control, a Nanopure water sample was inoculated, enriched with nutrients and treated in the same way as the substrate samples.

Blank-corrected curves describing cumulative O2 consumption and CO2 production during the single-substrate incubations were constructed (Supplementary Figure S2). Finally, the rates of O2 consumption and CO2 production were calculated from the slopes of the curves during the periods of apparent linear respiratory activity, between the lag phase and stationary phase (see details in Supplementary Figure S2).

Additional analyses of ecosystem properties

Site and catchment characteristics were determined from a digital elevation model in ArcGIS 10 (Esri, Redlands, CA, USA). Total phosphorus was measured using the molybdenum-blue method after persulfate digestion, DOC on an OI Analytical TIC/TOC Analyzer and water color at 440 nm (and other wavelengths) using a UV/Vis UltroSpec 2100 spectrophotometer (Biochrom Ltd, Cambridge, UK). Phytoplankton primary production and the ecosystem P:R ratio (primary production divided by total respiration) were calculated from O2 saturation, δ18O of dissolved O2, δ18O of water and community respiration, according to Quiñones-Rivera et al. (2009). Oxygen isotopes were determined using routine methods at the G.G. Hatch Stable Isotope Laboratory (Ottawa, ON, Canada). For the purpose of these calculations, we assumed that the total respiration equaled the bacterial total CO2 (TCO2) production multiplied with the ratio between bacterial O2 consumption rates in unfiltered (P del Giorgio, unpublished) and filtered water (this study) measured using identical methodology. We further assumed 0 exchange of O2 between the mixed layer and the hypolimnion. All data needed to calculate primary production and P:R were available for 56 out of the 72 samples.

Substrate characterization

The ratio between absorbance at 254 and 365 nm (a254/a365), which tends to be negatively correlated to the average molecular weight of DOC (Dehaan, 1993; Dahlén et al., 1996), was calculated along with the specific ultraviolet absorbance (SUVA; a254 divided by DOC) that indicates contents of aromatic carbon (Weishaar et al., 2003). Fluorescence intensity was measured on a Shimadzu RF5301 PC (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), across excitation wavelengths of 250–450 nm and emission wavelengths of 280–600 nm. Modeling of fluorescence components (parallel factors) was conducted, on inner-filter effect-corrected samples (McKnight et al., 2001), with MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) using the DOMfluor 1.7 toolbox (Stedmon and Bro, 2008) (see description of components in Supplementary Figure S4). Biological lability (Bio-lability) and photoreactivity (UV-lability) expressed as DOC loss, calculated as the slopes of linear regression lines for DOC vs time, were obtained from 2-week 20 °C dark incubations with ambient microbial communities, and 48 h incubations under the equivalent of mid-day tropical sunlight in a solar simulator (Qsun Xe-1-BC, Q-Lab, Cleveland, OH, USA), respectively. DOC was determined every second day in the bio-lability incubations and every 6–12 h in the UV-lability incubations. To obtain indices of substrate quality (rather than quantity), the lability measures were expressed as fractions of the DOC pool and the fluorescence component scores were expressed as fractions of the sum of all components. The cross-sample mean UV-sensitivity of each fluorescence component (% loss after 24 h solar simulation) was used to calculate an index of the total share (%) of UV-sensitive fluorescence in each sample.

Bacterial community characterization

The capacity of the communities to degrade 31 different substrates (each replicated three times) was measured using the Biolog Ecoplate (Biolog, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The respiration by the community reduces a tetrazolium dye that is included with each substrate, thus inducing a color development that is measured in an optical assay (Garland and Mills, 1991). We calculated the mean color development values for each class of compounds, measured at the overall ‘average well color development’ of 0.5.

Calculations

Measured CO2 production was recalculated to TCO2 (CO2+HCO3−+CO32−) production according to equations in Stumm and Morgan (1996). Thus, we accounted for the share of respired carbon that was transformed into carbonates, thus not being recorded by the pCO2 mini. Results from these calculations (Supplementary Figure S3) show that net transformation of respired carbon into carbonates was only significant in rare cases with extremely high pH combined with high ratios between alkalinity and CO2 production. In short, the equilibration constants that regulate the ionization fractions were calculated from incubation temperature. Alkalinity was calculated from in situ pH, dissolved inorganic carbon (measured using the IO Analytical TIC/TOC Analyzer) and temperature. The equilibration constants, in combination with alkalinity and incubation pCO2, was used to calculate the pH at each incubation time point, assuming constant alkalinity and that no other process other than CO2 production caused changes in pH (Oviatt et al., 1986). As the respiratory CO2 affects pH though a feedback loop involving changed ionization fractions, the incubation pH was not algebraically calculated, but solved iteratively using the ‘Solver’ module in Excel 2007. Finally, the share of produced TCO2 that did not contribute to measured CO2 (but to carbonates) was calculated as function of initial pH, temperature, and the ratio between alkalinity and cumulative TCO2 production (Supplementary Figure S3).

The standard error (s.e.) of each duplicate O2 consumption and TCO2 production estimate was calculated as the ‘standard error of slope’ using the LINEST function in Excel 2007. The s.e. of RQ was calculated by combining the s.e. of TCO2 production (s.e.[Y]) and O2 consumption (s.e.[X]) according to the equation:

Statistics

The regulation of RQ was analyzed exploratively by correlating RQ to principal components (PCs) that described the major patterns of variation in potential explanatory variables. PCs with eigenvalues greater than one were extracted using Varimax rotation (missing values replaced by mean). The extractions resulted in three models with two significant components each describing the variation in: (a) ecosystem properties, (b) substrate characters and (c) bacterial community functional traits (Biolog data).

All statistical analyses were performed in PASW Statistics 18 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Tests for comparing different means and to assess correlations were performed using two-tailed P-values except the tests for significant rates of O2 consumption and CO2 production during incubations (see above).

Results

The time required for observing significant linear changes in both TCO2 and O2 (86±45 h; mean ± s.d.) was negatively correlated with water temperature (r2=0. 50, n=72, P<0.001; data not shown). At higher temperatures (>18 °C), most incubations could be stopped after ∼48 h. On average, the TCO2-time and O2-time regressions comprised 5.0 time points and showed coefficients of determination (r2) of 0.88 and 0.92, respectively. The mean calculated standard error (s.e.; based on individual regression slopes) amounted to 18% of TCO2 production, 12% of O2 consumption and 24% of RQ. The between-replicate standard deviation of TCO2 production, O2 consumption and RQ was on average 23%, 10% and 24%, respectively. Measured RQs during bacterial assays with single substrates never deviated from theoretical RQ values by >20% (Figure 1). Control incubations showed non-significant changes in TCO2 and O2 (Supplementary Figure S2).

Measured RQs during single-substrate bacterial bioassays plotted against theoretical RQ values for complete aerobic oxidation of the different substrates. Error bars show the range of values obtained by duplicate measurements. The theoretical RQs of the substrates are derived from Table 1, except tryptophan that is attributed the typical text book value of 0.8 for protein and amino-acid degradation. For complete incubation data, see Supplementary Figure S3.

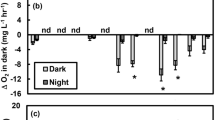

Bacterial TCO2 production and O2 consumption rates spanned two orders of magnitude, from 0.65 μM per day to 52 μM per day, generating RQ values in the range of 0.25–2.26. All respiration data from this study, compiled with unpublished and previously published data on freshwater bacterioplankton TCO2 production and O2 consumption are shown in Figure 2. Overall, the TCO2 production could be roughly calculated from O2 consumption according to the equation y=1.23x0.99 (r2=0.75, n=110, P<0.001; Figure 2), implying a general tendency of freshwater RQs to converge at values around 1.2 across all sites and respiration rates. The variation around the central tendency of RQ, however, was not random. The RQ showed distinct patterns of distribution along gradients of classical limnological variables, particularly in the lakes. Excluding the shallow ponds and tarns, there were highly significant negative correlations between RQ and in situ O2 saturation (r2=0.17, n=50, P<0.01; Figure 3a) and pH (r2=0.29, n=50, P<0.001; Figure 3b), and a relatively strong positive log–log relationship between RQ and in situ pCO2 (r2=0.42, n=50, P<0.001; Figure 3c). Overall, systems with very small areas (<0.10 km2, n=15) had significantly higher RQ than larger (>0.10 km2, n=57) systems (t=2.735, df=71, P<0.01, independent t-test; Figure 3d).

Relationship between the rate of bacterial production of TCO2 and the rate of bacterial consumption of dissolved oxygen (O2) shown for different freshwater systems (n=110). Diagonally dashed lines represent different bacterial RQs. The figure compiles present (‘Lakes’ and ‘Shallow ponds and tarns’), unpublished (‘Unpublished, rivers’; M. Berggren unpublished*) and previously published data (‘Literature, lakes’; Cimbleris and Kalff (1998)**). *Measured as in this study, but at a fixed temperature (20 °C) and controlled inorganic nutrient concentrations. **Measured during 2-day dark incubations at a controlled temperature of 21 °C using Winkler titration (O2 consumption) and gas chromatography (TCO2 production).

Relationships between the RQ of lake bacterioplankton (filled diamonds, n=51) and in situ (a) oxygen saturation, (b) pH and (c) partial pressure of CO2. The RQ of bacterioplankton in shallow ponds and tarns (open diamonds, n=21) is shown is shown for comparison, although not being significantly correlated to any of the explanatory variables. (d) Box and whisker plots of all RQ observations grouped by system depth, area and CO2 flux to air. Plus signs denote means and asterisks denote the significance of difference between means: **0.01, ***0.001 (independent samples t-test). Note the logarithmized axes of (c).

We further explored the distribution of RQs across all systems (lakes, shallow ponds and tarns) relative to ecosystem-level, substrate-level and bacterial community-level PCs of variation. At the ecosystem level, RQ was not correlated to the first PC (PC1), describing increasing tendencies in DOC, color, total phosphorus, shallowness and catchment wetland coverage (Figure 4a). However, there was a relatively strong negative correlation between RQ and ecosystem PC2, characterized by positive loadings for water surface area and variables related to ecosystem metabolism, indicating net autotrophy (O2 saturation, P:R and primary production). At the substrate level, samples with high RQ tended to score high on PC1, which was related to substrates of high photochemical reactivity, high SUVA (aromaticity) and high molecular weight, as indicated by low values on the absorbance ratio a254/a365 (Figure 4b). There was no significant correlation between RQ and substrate PC2, characterized by positive loadings for bio-lability and protein-like fluorescence, and negative loadings for most humic-like components. Also the PC analysis of Biolog data extracted two significant components, the first describing the capacity of the bacterial community to degrade polymers and second describing the capacity to degrade reduced compounds (Figure 4c). RQ showed negative correlations to the scores of both axes and particularly PC2. The highest RQ was found for the bacterial communities with the highest capacity to degrade highly oxidized organic acids.

PC loading plots, showing major axes (PCs) of variation in (a) ecosystem properties, (b) substrate quality and (c) bacterial community capacity to degrade different compounds on the Biolog Ecoplate. Percent explained variance by each PC is indicated in the axis title. Vectors show Pearson correlations between RQ and PC scores. Variables in italics have been log-transformed to improve normality. Asterisks and squares denote significant correlations with horizontal and vertical axis, respectively (single symbol P<0.05; double symbol P<0.01; triple symbol P<0.001).

Our results suggest a link between the degree of CO2 supersaturation (and O2 undersaturation) and the RQ in these systems. Most systems were supersaturated in CO2, and a total of 61 observations of CO2 efflux to the atmosphere were obtained with floating chambers. In the remaining 11 cases, typically representing situations of supersaturated O2 and undersaturated pCO2, the mean RQ was 0.81, which is significantly lower than the mean RQ of 1.35 in CO2 effluxing systems (t=3.358, df=71, P<0.001, independent t-test; Figure 3d).

The influence of variable RQ on the perceived contribution of BR to the measured CO2 fluxes in supersaturated systems is explored in Figure 5. We found that this contribution was systematically higher if BR was measured as TCO2 production rates compared with when BR was inferred from O2 consumption assuming a fixed RQ of 1 (Figure 5). The effect was particularly pronounced in lakes and in systems with small areas. In the lakes, the mean of BR contribution to CO2 efflux was 69% based on TCO2 production, but only 52% assuming an RQ of 1. In systems smaller than <0.10 km2, the contribution was 50% using the measured TCO2 production, and 32% assuming an RQ of 1 (Figure 5).

Contribution of epilimnetic bacterial respiration (BR) to CO2 efflux from different types of CO2 supersaturated freshwaters. White bars show BR calculated from O2 consumption assuming a fixed RQ of 1 and grey bars show BR measured directly as TCO2 production. Bars show mean values and error bars denote 95% confidence intervals of the means (based on log values). Asterisks denote the significance of difference between paired log means: *0.05, **0.01, ***0.001 (paired samples t-test).

Discussion

Our results clearly show that the common assumption of the bacterioplankton RQ fixed at a specific value, often 0.8 or 1.0, may not be justified. The estimates of RQ across 52 freshwaters sites tended to exceed 1 (Figure 2), and there were patterns of RQ along environmental gradients (Figures 3 and 4). We argue that our RQ estimates are robust and representative of ambient values, as the sensors were carefully calibrated and could effectively detect meaningful differences in RQ when bacterioplankton were respiring different single-carbon substrates (Figure 1). The mean replicate-level error of our RQ estimates, assessed either from calculated standard error (s.e.), or from standard deviation (s.d.) of replicates, was 24%, which is much less than the variability of the observed natural RQs (Figures 2 and 3). Moreover, by using the average of duplicate measurements and by compensating the error of individual RQs by a large sample number (n=72), we were able to capture consistent patterns of RQ across major gradients of ecosystem-level, substrate-level and bacterial community-level variations (Figure 4).

The overall trend for high RQ (Figure 2) is consistent with previous observations from temperate lakes (Cimbleris and Kalff, 1998), but in contrast to theoretical studies of bacterial metabolism, which have questioned large departures of RQs from 1 (del Giorgio and Williams, 2005b). In line with the often assumed bacterial use of relatively reduced phytoplanktonic compounds (Jansson et al., 2007), marine studies on plankton RQs have generally reported values slightly below, or around, 1 (Hopkinson, 1985; Oviatt et al., 1986; Berdalet et al., 1995; Robinson et al., 2002) (P del Giorgio, unpublished). Although high RQ might be physiologically explained by biogeochemical pathways of DOC degradation, it is not obvious how the community-level RQ could rise to values as high as 2 in response to cell biochemistry. For example, if bacteria used glucose for maximum possible enzyme production (see equation for complete glucose anabolism in Herbert, 1976), the RQ would only be ca 0.2 units higher than if the glucose was exclusively respired.

Instead, our study points to a substrate control of RQs. The RQ in the substrate experiments was close to 1 when bacteria were provided amino acid or carbohydrate DOC, but in the range of 1.5–4.6 for different organic acids (Figure 1). All these observations agreed well with theoretical RQs for complete aerobic oxidation of the different substrates (Table 1). Thus, the high RQ values that we observed in many natural epilimnetic samples are strongly indicative of bacterial use of compounds of high degree of oxidation, for example, low molecular weight organic acids. This type of compounds can be exported directly from terrestrial systems to streams (Berggren et al., 2010), but in lakes these compounds also originate from photochemical degradation of DOC by ultraviolet (UV) light (Kieber et al., 1989; Bertilsson and Tranvik, 1998), and the fact that RQ was strongly related to DOC UV-reactivity in our lakes (Figure 4) suggests that the preferential consumption of photochemically produced substrates may cause the high RQs observed.

We also observed some surprisingly low RQ values, outside of the range of theoretical RQs for different substrates (Table 1), especially at extremely high pH (Figure 3b). It is possible that the high pH and temperature in hard-water systems, in combination with microbial processes, caused some of the TCO2 to be transformed into calcite (Dittrich and Obst, 2004; Homa and Chapra, 2011), thus lowering the apparent RQ. Another possibility is that water column methane oxidation (Bastviken et al., 2008), for which the theoretical RQ is 0.5 (Table 1), partially explained the low RQs. However, pCH4 determinations performed on most samples using a headspace technique combined with gas chromatography (P del Giorgio, unpublished), revealed no significant relationships with RQ. Thus, methane was probably of small relative importance.

Systems that were net autotrophic (CO2 influx from atmosphere and high calculated P:R ratios) had a mean RQ of 0.81 (Figure 3d), suggestive of a dominant phytoplanktonic source of respired substrates (Anderson, 1995; Hedges et al., 2002). The remaining systems appeared to be net heterotrophic to varying degrees and had significantly higher mean RQs (1.35; Figure 3d). These patterns suggest that the net metabolic balance of freshwater ecosystems is not only related to their nutrient and organic matter inputs, but also to the nature of dominant pools of organic carbon that are consumed and respired by pelagic bacteria. Knowledge of the character of these pools may, in turn, contribute to understanding of why lakes in different regions differ in their relationships between DOC and pCO2 (Larsen et al., 2011). The fundamental role of substrate control of bacterial RQ and community metabolism was further highlighted by the Biolog results, showing that bacterial communities in high RQ systems were characterized by their capacity to degrade oxidized organic acids, whereas communities in low RQ systems were optimized for degrading reduced compounds, such as lipids (Figure 4c).

Many studies have characterized lake metabolic balances (as a P/R ratio) by comparing planktonic primary production (measured, for example, by 14C-bicarbonate incorporation) and planktonic respiration from O2 consumption, often assuming an RQ of 1 (del Giorgio et al., 1997; Koch et al., 2007). Our results suggest that assuming a fixed RQ is dampening the apparent variations in the net metabolic balance: In lakes that are net heterotrophic, the use of fixed RQ of around 1 will result in an underestimation of the actual degree of net heterotrophy, whereas the same fixed RQ will result in an underestimation of the degree of net autotrophy in more productive lakes. Moreover, high RQ values in net heterotrophic systems imply that bacteria have a significantly larger role in generating the excess pCO2, and thus the CO2 efflux, than what would be estimated based on the assumption of RQ=1 (Figure 5).

The above conclusions apply mostly to lakes, while shallow ponds and tarns showed less clear patterns in RQ (Figure 3). Overall, the contribution of BR to CO2 efflux was also smaller from ponds and tarns, in comparison to that of the deeper lakes (Figure 5). In shallow systems, the water column CO2 and O2 dynamics are probably dominated by benthic processes (Pace and Prairie, 2005; Gudasz et al., 2010) that take control over the regulation of pCO2 and O2 dynamics (Figure 3). However, regardless of the systems considered, there were no significant relationships between RQ and DOC, suggesting that it is not the amount of DOC, but rather its origin and composition that have a major role for the pathways of ecosystem metabolism.

Our results clearly show that variations in RQ can have profound implications on the perceived magnitude of BR and of the metabolic balance of the ecosystem (Figure 5). Although this study focuses on bacterial RQ along freshwater environmental gradients, there is no reason to think that other aquatic ecosystems, such as coastal and open oceans, will behave differently, thus, prompting the urgent need to assess bacterial RQ broadly.

References

Anderson LA . (1995). On the hydrogen and oxygen-content of marine phytoplankton. Deep Sea Res Part-I Oceanogr Res 42: 1675–1680.

Bastviken D, Cole JJ, Pace ML, Van de Bogert MC . (2008). Fates of methane from different lake habitats: connecting whole-lake budgets and CH4 emissions. J GeophysRes-Biogeosci 113: 13.

Battin TJ, Luyssaert S, Kaplan LA, Aufdenkampe AK, Richter A, Tranvik LJ . (2009). The boundless carbon cycle. Nat Geosci 2: 598–600.

Berdalet E, Packard T, Lagace B, Roy S, StAmand L, Gagne JP . (1995). CO2 production, O-2 consumption and isocitrate dehydrogenase in the marine bacterium Vibrio natriegens. Aqua Microbial Ecol 9: 211–217.

Berggren M, Laudon H, Haei M, Ström L, Jansson M . (2010). Efficient aquatic bacterial metabolism of dissolved low molecular weight compounds from terrestrial sources. ISME J 4: 408–416.

Berggren M, Laudon H, Jansson M . (2007). Landscape regulation of bacterial growth efficiency in boreal freshwaters. Global Biogeochem Cyc 21: GB4002.

Bertilsson S, Tranvik LJ . (1998). Photochemically produced carboxylic acids as substrates for freshwater bacterioplankton. Limnol Oceanogr 43: 885–895.

Cimbleris ACP, Kalff J . (1998). Planktonic bacterial respiration as a function of C : N : P ratios across temperate lakes. Hydrobiologia 384: 89–100.

Dahlén J, Bertilsson S, Pettersson C . (1996). Effects of UV-A irradiation on dissolved organic matter in humic surface waters. Env Int 22: 501–506.

Dehaan H . (1993). Solar UV-light penetration and photodegradation of humic substances in peaty lake water. Limnol Oceanogr 38: 1072–1076.

del Giorgio PA, Cole JJ, Cimbleris A . (1997). Respiration rates in bacteria exceed phytoplankton production in unproductive aquatic systems. Nature 385: 148–151.

del Giorgio PA, Condon R, Bouvier T, Longnecker K, Bouvier C, Sherr E et al. (2011). Coherent patterns in bacterial growth, growth efficiency, and leucine metabolism along a Northeast Pacific inshore-offshore transect. Limnol Oceanogr 56: 1–16.

del Giorgio PA, Pace ML . (2008). Relative independence of dissolved organic carbon transport and processing in a large temperate river: the Hudson river as both pipe and reactor. Limnol Oceanogr 53: 185–197.

del Giorgio PA, Williams PJ . (2005a). The global significance of respiration in aquatic ecosystems: from single cells to the biosphere. In: del Giorgio PA, Williams PJ (eds). Respiration in Aquatic Ecosystems. Oxford University Press: New York, pp 267–303.

del Giorgio PA, Williams PJ (eds) (2005b). Respiration in Aquatic Ecosystems. Oxford University Press: New York, p 315.

Dilly O . (2001). Microbial respiratory quotient during basal metabolism and after glucose amendment in soils and litter. Soil Biol Biochem 33: 117–127.

Dittrich M, Obst M . (2004). Are picoplankton responsible for calcite precipitation in lakes? Ambio 33: 559–564.

Garland JL, Mills AL . (1991). Classification and characterization of heterotrophic microbial communities on the basis of patterns of community-level sole-carbon-source utilization. Appl Env Microbiol 57: 2351–2359.

Granéli W, Lindell M, Tranvik L . (1996). Photo-oxidative production of dissolved inorganic carbon in lakes of different humic content. Limnol Oceanogr 41: 698–706.

Gudasz C, Bastviken D, Steger K, Premke K, Sobek S, Tranvik LJ . (2010). Temperature-controlled organic carbon mineralization in lake sediments. Nature 466: 478–481.

Guillemette F, del Giorgio PA . (2011). Reconstructing the various facets of dissolved organic carbon bioavailability in freshwater ecosystems. Limnol Oceanogr 56: 734–748.

Hedges JI, Baldock JA, Gelinas Y, Lee C, Peterson ML, Wakeham SG . (2002). The biochemical and elemental compositions of marine plankton: a NMR perspective. Mar Chem 78: 47–63.

Herbert D . (1976). Stoichiometric aspects of microbial growth. In: Dean ACR, Ellwood DC, Evans CGT, Melling J (eds). Continuous Culture 6: Applications and New Fields, John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, pp 1–30.

Homa ES, Chapra SC . (2011). Modeling the impacts of calcite precipitation on the epilimnion of an ultraoligotrophic, hard-water lake. Ecol Model 222: 76–90.

Hopkinson CS . (1985). Shallow-water benthic and pelagic metabolism - evidence of heterotrophy in the nearshore Georgia Bight. Mar Biol 87: 19–32.

Humborg C, Mörth CM, Sundbom M, Borg H, Blenckner T, Giesler R et al. (2010). CO2 supersaturation along the aquatic conduit in Swedish watersheds as constrained by terrestrial respiration, aquatic respiration and weathering. Global Change Biol 16: 1966–1978.

Jansson M, Persson L, DeRoos AM, Jones RI, Tranvik LJ . (2007). Terrestrial carbon and intraspecific size-variation shape lake ecosystems. Trends Ecol Evol 22: 316–322.

Karlsson J, Byström P, Ask J, Ask P, Persson L, Jansson M . (2009). Light limitation of nutrient-poor lake ecosystems. Nature 460: 506–509.

Karlsson J, Jansson M, Jonsson A . (2007). Respiration of allochthonous organic carbon in unproductive forest lakes determined by the Keeling plot method. Limnol Oceanogr 52: 603–608.

Kieber DJ, McDaniel J, Mopper K . (1989). Photochemical source of biological substrates in sea-water - implications for carbon cycling. Nature 341: 637–639.

Koch RW, Bukaveckas PA, Guelda DL . (2007). Importance of phytoplankton carbon to heterotrophic bacteria in the Ohio, Cumberland, and Tennessee rivers, USA. Hydrobiologia 586: 79–91.

Larsen S, Andersen T, Hessen DO . (2011). The pCO(2) in boreal lakes: organic carbon as a universal predictor? Global Biogeochem Cyc 25: 8.

Marchand D, Prairie YT, del Giorgio PA . (2009). Linking forest fires to lake metabolism and carbon dioxide emissions in the boreal region of Northern Quebec. Global Change Biol 15: 2861–2873.

McCallister SL, del Giorgio PA . (2008). Direct measurement of the delta C-13 signature of carbon respired by bacteria in lakes: linkages to potential carbon sources, ecosystem baseline metabolism, and CO2 fluxes. Limnol Oceanogr 53: 1204–1216.

McKnight DM, Boyer EW, Westerhoff PK, Doran PT, Kulbe T, Andersen DT . (2001). Spectrofluorometric characterization of dissolved organic matter for indication of precursor organic material and aromaticity. Limnol Oceanogr 46: 38–48.

Middelboe M, Søndergaard M . (1993). Bacterioplankton growth yield - seasonal variations and coupling to substrate lability and beta glucosidase activity. App Env Microbiol 59: 3916–3921.

Münster U, Einio P, Nurminen J, Overbeck J . (1992). Extracellular enzymes in a polyhumic lake - important regulators in detritus processing. Hydrobiologia 229: 225–238.

Oviatt CA, Rudnick DT, Keller AA, Sampou PA, Almquist GT . (1986). A comparison of system (O-2 and CO2) and C-14 measurements of metabolism in estuarine mesocosms. Mar Ecol-Prog Ser 28: 57–67.

Pace ML, Prairie YT . (2005). Respiration in lakes. In: Del Giorgio PA, Williams PJ (eds). Respiration in Aquatic Ecosystems. Oxford University Press: New York, pp 103–121.

Prairie YT, Bird DF, Cole JJ . (2002). The summer metabolic balance in the epilimnion of southeastern Quebec lakes. Limnol Oceanogr 47: 316–321.

Pullin MJ, Bertilsson S, Goldstone JV, Voelker BM . (2004). Effects of sunlight and hydroxyl radical on dissolved organic matter: bacterial growth efficiency and production of carboxylic acids and other substrates. Limnol Oceanogr 49: 2011–2022.

Quiñones-Rivera ZJ, Wissel B, Justic D . (2009). Development of productivity models for the northern Gulf of Mexico based on oxygen concentrations and stable isotopes. Estuaries Coasts 32: 436–446.

Robinson C, Serret P, Tilstone G, Teira E, Zubkov MV, Rees AP et al. (2002). Plankton respiration in the Eastern Atlantic Ocean. Deep Sea Res Part-I Oceanogr Res 49: 787–813.

Stedmon CA, Bro R . (2008). Characterizing dissolved organic matter fluorescence with parallel factor analysis: a tutorial. Limnol Oceanogr-Methods 6: 572–579.

Stumm W, Morgan JJ . (1996). Aquatic Chemistry - Chemical Equilibria and Rates in Natural Waters, 3rd edn. John Wiley & Sons: New York, USA.

Takahashi T, Broecker WS, Langer S . (1985). Redfield ratio based on chemical-data from isopycnal surfaces. J Geophys Res-Oceans 90: 6907–6924.

Tranvik LJ, Downing JA, Cotner JB, Loiselle SA, Striegl RG, Ballatore TJ et al. (2009). Lakes and reservoirs as regulators of carbon cycling and climate. Limnol Oceanogr 54: 2298–2314.

Vachon D, Prairie YT, Cole JJ . (2010). The relationship between near-surface turbulence and gas transfer velocity in freshwater systems and its implications for floating chamber measurements of gas exchange. Limnol Oceanogr 55: 1723–1732.

Weishaar JL, Aiken GR, Bergamaschi BA, Fram MS, Fujii R, Mopper K . (2003). Evaluation of specific ultraviolet absorbance as an indicator of the chemical composition and reactivity of dissolved organic carbon. Env Sci Technol 37: 4702–4708.

Winkler LW . (1888). Die Bestimmung des im Wasser gelösten Sauerstoffes. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft 21: 2843–2854.

Acknowledgements

The study was financed through the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and Hydro-Québec Industrial Research Chair in the Carbon Biogeochemistry of Boreal Aquatic Ecosystems. MB was supported by a postdoctoral scholarship from the Swedish Research Council (VR) and JFL by a NSERC PhD scholarship. We thank Geneviève Thibodeau and the following for field and laboratory assistance: Alice Parkes, Annick St-Pierre, Audrey Campeau, Christopher Siddell, Dominic Vachon, Jean-Philippe Desindes, Juan-Pablo Nino Garcia, Justine Lacombe, Lisa Fauteux, Marcela Bastidas Navarro, Maria-Carolina Garcia Chaves, Nicolas Fortin, Rabia Oukaci and Véronique Ducharme Riel. Yves Prairie and Francois Guillemette provided constructive comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on The ISME Journal website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berggren, M., Lapierre, JF. & del Giorgio, P. Magnitude and regulation of bacterioplankton respiratory quotient across freshwater environmental gradients. ISME J 6, 984–993 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.157

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.157

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Fungal parasitism on diatoms alters formation and bio–physical properties of sinking aggregates

Communications Biology (2023)

-

Oxygen consumption and formation of recalcitrant organic carbon from the decomposition of free-floating macrophyte leachates

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Seasonal variation and importance of catchment area composition for transport of bioavailable carbon to the Baltic Sea

Biogeochemistry (2023)

-

Practical Guide to Measuring Wetland Carbon Pools and Fluxes

Wetlands (2023)

-

Photoheterotrophy by aerobic anoxygenic bacteria modulates carbon fluxes in a freshwater lake

The ISME Journal (2022)