Abstract

During smile evaluation and anterior esthetic construction, the anatomic and racial variations should be considered in order to achieve better matching results. The aims of this study were to validate an objective method for recording spontaneous smile process and to categorize the smile and upper lip curvature of Chinese Han-nationality youth. One hundred and eighty-eight Chinese Han-nationality youths (88 males and 100 females) ranged from 20 to 35 years of age were selected. Spontaneous smiles were elicited by watching comical movies and the dynamics of the spontaneous smile were captured continuously with a digital video camera. All subjects’ smiles were categorized into three types: commissure, cuspid and gummy smile based on video editing software and final images. Subjects’ upper lip curvatures were also measured and divided into three groups: upward, straight and downward. Reliability analysis was conducted to obtain intra-rater reliabilities on twice measurements. The Pearson Chi-square test was used to compare differences for each parameters (α=0.05). In smile classification, 60.6% commissure smile, 33.5% cuspid smile and 5.9% gummy smile were obtained. In upper lip measurement, 26.1% upward, 39.9% straight and 34.0% downward upper lip curvature were determined. The commissure smile group showed statistically significant higher percentage of straight (46.5%) and upward (40.4%) in upper lip curvatures (P<0.05), while cuspid smile group (65.1%) and gummy smile group (72.7%) showed statistically significant higher frequency in downward upper lip curvature (P<0.05). It is evident that differences in upper lip curvature and smile classification exist based on race, when comparing Chinese subjects with those of Caucasian descent, and gender.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Smile is the most complex and sophisticated facial expression, formed from synergic action of facial expression muscles.1 Previous reports have discussed the anatomical movements of the mouth during smile and the resultant effect of dental exposure.1,2,3 Rubin classified smiles into three anatomical types according to various attachment points and strengths of the surrounding perioral muscles.1 From a dental point of view, an esthetically attractive smile involves a harmonious relationship among anterior teeth, the gingival scaffold and the lip framework.4,5 Upper lip curvature can be divided into three categories according to the positioning of the corners of the mouth relative to the center of the upper lip lower border.6,7 Many investigations5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 on smile esthetics used static pictures or direct measurements. Traditionally, static photographic techniques could only capture still smile images at certain time points, which made it difficult to obtain the precise and natural moment of smile process, even during a posed smile.5,6 With the evolution of digital imaging, studies with contemporary available digital videography had shown that a spontaneous smile of joy can be achieved with a more observational and less patient-interfering approach.17,18,19,20,21 Although the esthetic smile has been well studied and published, these data have been nearly all derived from Caucasian samples except for a few data derived from Asian countries.7,10,11,19,22 Several authors have addressed racial variations among facial parameters.23,24 Richardson24 published that the components of the face closer to the alveolar and dental areas show the greatest differences among ethnic and racial groups. Johnson23 reported how knowledge of racial ‘norms’ for facial appearance might aid practitioners to determine anterior esthetics. An understanding of these norms would lead to better esthetics and treatment plans and then be in harmony with the facial appearance for patients of different races. Therefore, it would be useful to establish some desirable characteristic features of smiles to help achieve optimum results in esthetic oral rehabilitation for Chinese patients. The present study sought to establish an objective method for recording dynamic smile process and to categorize spontaneous smile and upper lip curvature in Chinese Han-nationality youths. The null hypotheses for this study were that there were no significant differences in frequencies for smile classification and upper lip curvature between Chinese subjects and Caucasian descent.

Materials and methods

Sampling and selection criteria

Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of Peking University Medical Ethics Committee (IRB no. 0902-12) for this study and the subject selection process. Basically, the subjects obtained were students and staff from the Peking University Health Science Center. It was explained to potential subjects that this was a study on dynamic smile and lip shape by watching three short comedic films along with a video clip capturing subjects’ face continuously for approximate 3 min. The inclusion criteria were: (i) Chinese Han-nationality youths between 20 and 35 years of age; (ii) full maxillary and mandibular dentition with erupted second molars; (iii) skeletal and dental class I relationships; (iv) no anterior malposition conditions such as severe crowding, spacing, tipping, or rotations; (v) no symptoms of facial paralysis or lip irregularities; (vi) no anterior caries lesions, restorations or prostheses, active gingival and periodontal disease, gingival recessions; and (vii) no history of orthodontic treatment or maxillofacial surgery.

Recording and measurement during spontaneous smiling

Study was conducted in a studio by a professional photographer with a digital video camera (HDR-SR12E; Sony Corp., Tokyo, Japan) mounted on a tripod at a distance of 150 cm from the subject’s upper lip. The camera lens was adjusted to be parallel to the apparent occlusal plane and the camera focused only on the portion between the nose and chin. The subject was instructed to sit and hold the head naturally after leveling with the Frankfort horizontal plane during the study period (Figure 1). In addition, one millimeter scale was placed adjacent to the subject’s right tragus and used as an external reference. A laptop (INSPIRON 1545, Dell, Austin, TX, USA) was placed at the subject’s eye level behind the camera. In order to prompt spontaneous smiling, the subjects were provided three 1-min-long comedic films to watch during video recording. Three complete processes of spontaneous smile including rest position to full smile were recorded with minimal intrusion of the subject while subjects were watching the films.

The video clip was downloaded to a computer and processed with a video-editing software (Sony Vegas Pro 10.0; Sony Creative Software Inc., Middleton, WI, USA). Each frame was reviewed and analyzed. Two frames including the subject’s lip at rest position and a maximum commissure-to-commissure dynamic smile were captured. These frames were converted into a JPEG file and renamed in Windows XP Professional (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) with the subjects’ numbers. Each file was opened in Adobe Photoshop CS3 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) and the image size of each file was adjusted by using the millimeter ruler as a reference.

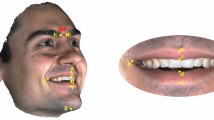

In order to categorize smile patterns of subjects, Rubin classification1 was adapted and shown in Figure 2. In the commissure smile, the corners of the mouth turn upward due to the pull of the zygomaticus major. In the cuspid smile, the upper lip is elevated uniformly without the corners of the mouth turning upward; the entire lip rises like a window shade. In the complex or gummy smile, the upper lip moves superiorly, as in the cuspid smile. But the lower lip usually moves inferiorly in a smile fashion.19

In addition, curvatures of upper lip during full smile were measured and categorized using the following criteria (Figure 3):6,7 (i) upward lip curvature means that the corner of the mouth is at 1 mm higher than a horizontal line drawn through the center of the lower border of the upper lip; (ii) straight lip curvature means that the corner of the mouth at or within 1 mm above and below a horizontal line drawn through the center of the lower border of the upper lip; (iii)downward lip curvature means that the corner of the mouth is at more than 1 mm lower than a horizontal line drawn through the center of the lower border of the upper lip.

Statistical analysis

All hypotheses were tested statistically at α=0.05. The kappa statistics test was used to exam the reliability of the data recorded by the rater at times 1 and 2 with 1 week apart. The Pearson Chi-square test was used to analyze the differences between male and female subjects in the frequencies of smile classification and curvature of upper lip (α=0.05).

Results

The results of the re-testing in categorizing the dynamic smiles and upper lip curvature at different measurements are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The kappa statistic test obtained a score of 0.85 for smile classification and a score of 0.86 for upper lip curvature. No statistically significant difference was determined in classification of subjects between twice measurement by the same rater (P>0.05).

The frequencies of smile classification and upper lip curvature are shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Female subjects obtained significantly higher percentage of commissure smile and lower percentage of cuspid smile than male subjects (P<0.05) in smile classification. In upper lip measurements, female subjects expressed statistically significant higher percentage in upward curvature and lower percentage in downward curvature during dynamic smile than male subjects in this study (P<0.05).

The distributions of each type of upper lip curvature in different smile classifications are shown in Figure 4. Subjects with commissure smile displayed predominantly either upward or straight curvature of their upper lip contour. There are statistically significant higher percentage of expressing downward curvature of their upper lips in both cuspid and gummy type of smiles (P<0.05).

Discussion

Spontaneous smiling should be the logical focus point for the esthetic diagnosis of lip–tooth relationship during smiling. The fast onset and fading out of a spontaneous smile makes it impossible to capture in the right moment with a static photograph. Therefore, it is proposed to switch from static to dynamic video-recording of the smile for diagnostic purpose. The results of this study indicated that spontaneous smiles were measured reproducibly with the digital videographic method which showed a high level of reliability in making judgments on the smiles.4,5,12,21 The Pearson correlations for the measurements obtained from 0.85 for smile classification and 0.86 for upper lip curvature respectively, and were highly acceptable.25

Comparisons with approximate data of frequencies for smile and curvature of upper lip derived from previous studies are shown in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. Of all the different kinds of smile, the commissure smile was determined to be 60.6%; this agrees with other studies measuring smile.1,4,8,22 Our finding that 5.9% of the subjects had a gummy smile is consistent with previous reports.1,4,8

Murakami et al.22 reported a higher percentage of gummy smile that related to the younger age (18±3 years) of the subjects observed. The similar results were obtained and reported by Peck et al.14 that 26% of their samples had a mean age of 15.5 years, demonstrated a high or gummy smile. In addition, there was a significant gender difference in smile line frequency: low smile lines were predominantly a male characteristic (2.5 to 1) and gummy smile was predominantly a female characteristic (2 to 1).15,16 It was surprising to find significant male–female difference in frequencies of smile classification and upper lip curvatures (Tables 3 and 4). Male displayed significantly more gingival tissue was determine and gummy smile was predominantly a male characteristic in Chinese youths (Table 3). Therefore, the first hypothesis of no significant differences in frequencies for smile classification is partially accepted.

Regarding the upper lip curvature, the hypothesis of no significant differences in frequencies for upper lip curvature is rejected. According to the mean smile scores reported by Hulsey,8 the group of upward lip curvature contained the most subjects, while the group of straight lip curvature contained the fewest subject. However, in the current study, the group of upward lip curvature obtained a lower percentage, while the group of straight lip curvature contained the most subjects (Table 4). The results were similar to previous studies of Korean subjects (Table 6).7

Furthermore, the present study attempted to explore the relationship between smile classification and upper lip curvature. Our results showed that most of subjects with commissure smile appeared as straight (46.5%) or upward (40.4%) upper lip curvatures, while subjects with cuspid smile or gummy smiles mostly appeared as downward upper lip curvature (65.1% and 72.7%, respectively). It appears that good smiles can be found with either a curved-upper lip, a straight upper lip, or even a curved-down upper lip. Sawyer et al.26 in their quantitative analysis of normal smile report indicated that the cuspid smile is a subtle smile and usually has a significant overlap with the commissure smile. Hulsey8 pointed out that smiles with the upper lip curving downward were not quite as attractive in his report of esthetic evaluation of lip–teeth relationship. Our study firstly indicated that there were certain relation between upper lip curvature and Rubin’s smile classification. Upper lip curvature might be a major factor of smile classification based on the anatomical feature of upper lip and the relationship of these two parameters still needs further investigation.

The position and movement of upper lip plays a major role in developing smiles.1 Particular in the case of gummy smile patients, who have the muscular ability to raise the upper lip significantly higher than average on smiling.13 Chiu and Clark27 studied the facial soft tissue profile of the southern Chinese and found that a more obtuse nasolabial angle, almost 100 °, occurred among female instead of right-angled for male. In recent studies about facial movement, men are found to have statistically significant wider faces and larger movement than women.28,29,30 Tzou et al.29 reported the difference of facial movement between Europeans and Asians and found that Europeans had generally larger facial movements than Asians. A complete explanation for the significant gender differences in frequency of the gummy smile remains indeterminable. From a practical point of view, the risk of anterior esthetic rehabilitation will increase significantly in a gummy case. For example, a natural looking anterior implant restoration, including correct shape of the alveolar bone, a harmonious gingival line and an interproximal dental papilla to the contact point, is not always achievable in clinical practice. In that case, the height of the lip line is decisive whether the esthetic shortcomings of esthetic therapy are masked by the upper lip or just revealed.31 In clinical practice, the smile classifications also raise additional considerations concerning the notions of harmony and symmetry between prosthetic and gingival features. In the second type of smile—the cuspid smile—the lip line of the upper cuspids moves upward significantly while smiling, making reconstruction of the cuspid area extremely important in these patients. With the third type of smile—the gummy smile—though relatively infrequent in Chinese patients, extra attention must be paid to the exposure of upper and lower gingivae. In these cases, longer clinical crown lengths may help compensate for the unbalanced proportion of exposed gingivae to crowns.

Limitations of sample size, although consistent with previous published reports, also must temper extrapolation of outcomes from this study. It is evident that differences based on race and gender exist in upper lip curvature and smile classifications. Nevertheless, this investigation established some measurable components from which further studies may be derived; an example includes further examining the racial and genetic basis in the differences found in the present study. It may also be worthwhile to investigate whether the present smile classification and upper lip curvature may be combined with other smile indices, such as smile arc, smile line, buccal corridor, etc., and whether these esthetics indices could be efficiently integrated into clinical practice.

Conclusion

One hundred and eighty-eight Chinese Han-nationality youths ranged from 20 to 35 years of age were selected and made dynamic smile evaluation by using an objective spontaneous smile process capturing method. In upper lip curvature and smile classifications, differences clearly exist based on race, when comparing Chinese subjects with those of Caucasian descent, and gender.

References

Rubin LR . The anatomy of a smile: its importance in the treatment of facial paralysis. Plast Reconstr Surg 1974; 53( 4): 384–387.

Janzen EK . A balanced smile-A most important treatment objective. Am J Orthod 1977; 72( 4): 359–372.

Matthews TD . The anatomy of a smile. J Prosthet Dent 1978; 39( 2): 128–134.

Desai S, Upadhyay M, Nanda R . Dynamic smile analysis: Changes with age. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2009; 136( 3): 310.e1–310.e10.

Van der Geld P, Oosterveld P, Berge SJ et al. Tooth display and lip position during spontaneous and posed smiling in adults. Acta Odont Scand 2008; 66( 4): 207–213.

Al-Johany SS, Alqahtani AS, Alqahtani FY et al. Evaluation of different esthetic smile criteria. Int J Prosthodont 2011; 24( 1): 64–70.

Dong JK, Jin TH, Cho HW et al. The esthetics of the smile: a review of some recent studies. Int J Prosthodont 1999; 12( 1): 9–19.

Hulsey CM . An esthetic evaluation of lip-teeth relationship present in the smile. Am J Orthod 1970; 57( 2): 132–144.

Moore T, Southard KA, Casko JS et al. Buccal corridors and smile esthetics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2005; 127( 2): 208–213.

Owens EG, Goodacre CJ, Loh PL et al. A multicenter interracial study of facial appearance. Part 1: a comparison of extraoral parameters. Int J Prosthodont 2002; 15( 3): 273–282.

Owens EG, Goodacre CJ, Loh PL et al. A multicenter interracial study of facial appearance. Part 2: a comparison of intraoral parameters. Int J Prosthodont 2002; 15( 3): 283–288.

Parekh SM, Fields HW, Beck M et al. Attractiveness of variations in the smile arc and buccal corridor space as judged by orthodontists and laymen. Angle Orthod 2006; 76( 4): 557–563.

Peck S, Peck L . Selected aspects of the art and science of facial esthetics. Semin Orthod 1995; 1( 2): 105–126.

Peck S, Peck L, Kataja M . The gingival smile line. Angle Orthod 1992; 62( 2): 91–100.

Peck S, Peck L, Kataja M . Some vertical lineaments of lip position. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1992; 101( 6): 519–524.

Tjan AH, Miller GD . Some esthetic factors in a smile. J Prosthet Dent 1984; 51( 1): 24–28.

Kang YS, Bae YC, Hwang SM et al. A simple and quantitative method for three-dimensional measurement of normal smiles. Ann Plast Surg 2005; 54( 4): 379–383.

Parekh S, Fields HW, Beck FM et al. The acceptability of variations in smile arc and buccal corridor space. Orthod Craniofacial Res 2007; 10( 1): 15–21.

Sarver DM, Ackerman MB . Dynamic smile visualization and quantification: Part I. Evolution of the concept and dynamic records for smile capture. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003; 124( 1): 4–12.

Tomat LR, Manktelow RT . Evaluation of a new measurement tool for facial paralysis reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005; 115( 3): 696–704.

Van der Geld P, Oosterveld P, Van Waas MA et al. Digital videographic measurement of tooth display and lip position in smiling and speech: reliability and clinical application. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007; 131( 3): 301.e1–301.e8.

Murakami Y, Deguchi T, Kageyama T et al. Assessment of the esthetic smile in young Japanese women. Orthod Waves 2008; 67( 5): 104–112.

Johnson PF . Racial norms: Esthetic and prosthodontics implactions. J Prosthet Dent 1992; 67( 4): 502–508.

Richardson ER . Racial differences in dimensional traits of human face. Angle Orthod 1980; 50( 4): 301–311.

Landis JR, Koch GG . The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33( 1): 159–174.

Sawyer AR, See M, Nduka C . Quantitative analysis of normal smile with 3D stereophotogrammetry – an aid to facial reanimation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2010; 63( 1): 65–72.

Chiu CSW, Clark RKF . The facial soft tissue profile of the southern Chinese: Prosthodontic consideration. J Prosthet Dent 1992; 68( 5): 839–850.

Ferrario VF, Sforza C, Serrao G . A three-dimensional quantitative analysis of lips in normal young adults. Cleft Palate Craniofacial J 2000; 37( 1): 48–54.

Tzou CHJ, Giovanoli P, Ploner M et al. Are there ethnic differences of facial movements between Europeans and Asians? Brit J Plast Surg 2005; 58( 2): 183–195.

Wang D, Qian G, Zhang M et al. Differences in horizontal, neoclassical facial canons in Chinese (Han) and north American Caucasian population. Aesth Plast Surg 1997; 21( 4): 265–269.

Cune MS, Meijer GJ, Koole R . Anterior tooth replacement with implant in grafted alveolar cleft sites – a case series. Clinoral Impl Res 2004; 15( 5): 616–624.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Hao Zhang and Dr Huan-Xin Meng for their suggestions in the preparation of the manuscript. The authors appreciate the technical supports provided from Zhan-Qiang Cao (Engineer), and the related information provided from Dr Di Le.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, LZ., Hu, WJ., Zhang, YL. et al. Analysis of dynamic smile and upper lip curvature in young Chinese. Int J Oral Sci 5, 49–53 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2013.17

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2013.17

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Lip repositioning surgery for gummy smile: 6-month clinical and radiographic lip dimensional changes

Clinical Oral Investigations (2021)

-

Evaluation of the maxillary midline, curve of the upper lip, smile line and tooth shape: a prospective study of 140 Caucasian patients

BMC Oral Health (2020)

-

Analysis of different characteristics of smile

BDJ Open (2020)

-

An evaluation of the influence of teeth and the labial soft tissues on the perceived aesthetics of a smile

British Dental Journal (2017)

-

A novel three-dimensional smile analysis based on dynamic evaluation of facial curve contour

Scientific Reports (2016)