Abstract

Objective:

Individual behaviour change to reduce obesity requires awareness of, and concern about, weight. This paper therefore describes how young adults, known to have been overweight or obese during early adolescence, recalled early adolescent weight-related awareness and concerns. Associations between recalled concerns and weight-, health- and peer-related survey responses collected during adolescence are also examined.

Design:

Qualitative semi-structured interviews with young adults; data compared with responses to self-report questionnaires obtained in adolescence.

Participants:

A total of 35 participants, purposively sub-sampled at age 24 from a longitudinal study of a school year cohort, previously surveyed at ages 11, 13 and 15. Physical measures during previous surveys allowed identification of participants with a body mass index (BMI) indicative of overweight or obesity (based on British 1990 growth reference) during early adolescence. Overall, 26 had been obese, of whom 11 had BMI⩾99.6th centile, whereas 9 had been overweight (BMI=95th–97.9th centile).

Measures:

Qualitative interview responses describing teenage life, with prompts for school-, social- and health-related concerns. Early adolescent self-report questionnaire data on weight-worries, self-esteem, friends and victimisation (closed questions).

Results:

Most, but not all recalled having been aware of their overweight. None referred to themselves as having been obese. None recalled weight-related health worries. Recollection of early adolescent obesity varied from major concerns impacting on much of an individual's life to almost no concern, with little relation to actual severity of overweight. Recalled concerns were not clearly patterned by gender, but young adult males recalling concerns had previously reported more worries about weight, lower self-esteem, fewer friends and more victimisation in early adolescence; no such pattern was seen among females.

Conclusion:

The popular image of the unhappy overweight teenager was not borne out. Many obese adolescents, although well aware of their overweight recalled neither major dissatisfaction nor concern. Weight-reduction behaviours are unlikely in such circumstances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The health and economic costs of rising levels of obesity in most countries of the world have led to increasingly urgent calls for action.1 Action at an individual level will only occur if individuals are aware of, and concerned about, their obesity.2 This may be particularly important at younger ages, given the tracking of both obesity3, 4 and obesity-related behaviours.5 This qualitative paper explores how young adults known to have been overweight or obese at some point during early adolescence recalled their early adolescent weight-related awareness and concerns. We begin with a brief review of the literature on the psychosocial impact of obesity on children and adolescents.

Many quantitative studies have focused on the experiences of overweight or obese children and adolescents compared with healthy-weight peers. From very young ages, those who are obese are less preferred as friends and more likely to be characterised in negative ways or victimised.6, 7 Even though obesity is more commonplace and increasingly ‘normal’,8 stigmatisation appears to be as likely now as in the 1960s.9 There is also evidence that obese children and adolescents, particularly females, are more dissatisfied with their bodies than those of lesser weight.10 However, studies of community-based samples tend to find no, or only very weak associations between obesity and levels of depression.10 In addition, and despite evidence that self-esteem is associated with weight-related factors such as body image,11 community-based studies generally find only small differences in self-esteem between obese and non-obese children and adolescents.10, 12, 13

Psychological distress appears strongly associated with concern about weight and shape, regardless of body mass index (BMI), described by one paper as ‘feeling fat rather than being fat’.14 This is important because studies report that overweight and obese children and adolescents, particularly males, tend to perceive their body size as smaller than it really is.15, 16 There is also evidence to suggest that among children and adolescents17 as well as adults18 there has been a secular decrease in the proportion perceiving themselves as overweight.

Findings such as these, suggesting that not all those classed as overweight or obese are aware of their weight status, together with evidence that many, but not all, overweight young people are stigmatised,19 point to the need for qualitative studies to explore why such variation exists. However, in contrast to the large amount of quantitative research on the psychosocial impact of obesity on children and adolescents, only a handful of qualitative studies have focused on the lived experiences of overweight or obese children or adolescents themselves. Some of these include samples drawn from weight-loss clinics which convey ‘miserable’ school experiences, lack of friends and experience of victimisation among English 9–11 year olds,20 wanting to lose weight due to bullying and ‘social torment’ among English 9–14 year olds21 and ridicule and embarrassment, lack of close peer relationships and feelings of difference among very obese American adolescents.22 However, as one of these papers points out,21 these clinical samples may not reflect the views of the ‘unengaged obese child’, and studies of community-based samples are rather different. For example, a study of American 8–12 year olds found that their overweight or obesity impacted on social aspects of their lives, with descriptions of teasing and a desire to be liked, but also that over one third of the sample thought they were normal weight or underweight23 and a comparison of American adolescents sampled as weight maintainers or losers via routine health-centre weight charts found many expressed self-acceptance about their weight.24 Interviews with Scottish 13–14 year olds from a socio-economically disadvantaged area found not all overweight or obese teenagers in their sample were bullied, perceived their bodies as fat or unacceptable or strived for thinness.25 A recent systematic review of views about obesity, body size, shape and weight among 4–11 year olds found ‘children, unless they were very overweight, often did not see body shape as an immediately relevant issue’ (p3), and when overweight was identified as an issue, it was in relation to its social and psychological, rather than health, consequences.26 The review also noted that research in this area was very limited in scope and tended to draw from children of healthy weight.

The present study draws on interviews with young adults known to have been overweight or obese at some point during early adolescence. It aims to describe how they recalled their early adolescent weight-related awareness and concerns, and to relate these to survey responses collected during adolescence.

Materials and methods

Participants

A total of 35 participants were sub-sampled at age 24 for a project on adolescent experiences of obesity and weight-change27 from the West of Scotland 11–16/16+ Study. This was a longitudinal study of a single school year cohort, resident in and around Glasgow city, first surveyed in 1994–5, at age 11, in their final year of primary schooling (N=2 586; 93% of issued sample). The cohort was followed up in school-based surveys at ages 13 and 15. At each stage, height and weight measurements were taken, allowing the calculation of BMI. Background social class was derived from information on the occupation of the head of the household, obtained mainly via parental self-completion questionnaire when participants were aged 11.28

Recruitment

Purposive sampling was employed in order to identify young adult participants who had BMIs indicative of overweight or obesity at some point during early adolescence, defined as a BMI s.d. score above the 95th centile compared with the British 1990 growth reference.29 Potential participants were invited to take part, via letters describing the study as giving people ‘the chance to really talk about their lives’ in contrast to the early questionnaire surveys. The letters further noted that ‘We are particularly interested in talking to people who have had an above average build at some point in their lives’. The terms ‘overweight’ and ‘obese’ were not used as ‘obese’ is considered derogatory and upsetting,30 participants who had not become obese adults might have regarded the study as irrelevant and those who were obese might not have perceived themselves as such.31, 32

Of the 69 approached, 22 could not be contacted (letters returned, out of touch with family), 5 had moved too far away and 1 had died. Of the rest, only 6 refused to participate; the remaining 35 were interviewed in 2008. In all, 19 participants were from non-manual and 13 from manual family backgrounds; social class data were missing for the remaining 3.

Table 1 shows the classification of the 35 participants as (‘extremely’/‘very’) ‘obese’, ‘overweight’ or ‘healthy weight’ at ages 11, 13 and 15. These classifications were made on the basis of their BMI at each age, compared with UK reference data to allow for variation with gender and age,29 using thresholds proposed by a recent systematic review.33

Interviews

The semi-structured interviews began with a picture task using photos selected from www.gettyimages.com depicting young adults of different body sizes (healthy weight and obese), doing various, largely health-related activities (eating sweets or salads, sitting, exercising, smoking and shopping). Participants were asked to sort the photos into ‘healthy’ vs ‘unhealthy’ and ‘happy’ vs ‘unhappy’ in order to stimulate discussion related to perceptions of bodies and health, and then they were asked to describe themselves and their lives as a teenager; a typical school- and weekend-day; hobbies, interests and health-related behaviours; significant others, particularly people from school; teenage concerns, with prompts for school-, social- and health-related concerns; and finally changes as they became young adults. The interviews were audio-recorded with participants' consent.

11–16/16+ Study measures

Several measures from the self-completion questionnaires administered at ages 11, 13 and 15 are also included in this paper. Participants were asked whether they were ‘worried about putting on weight’ with ‘yes’ or ‘no’ options. Questionnaires included a 10-item self-esteem scale (based on Rosenberg,34 with items such as ‘I am pretty sure of myself’). Four-point responses were summed to produce a total score, dichotomised into ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ self-esteem for analytic purposes. The nurses who carried out physical measurements also asked the standard UK General Household Survey question ‘Over the last 12 months, would you say your health on the whole has been good, fairly good or not good?’ with answers dichotomised into ‘good’ versus ‘fairly’/‘not good’ for analytic purposes. The questionnaires asked ‘how many friends do you have altogether?’ with responses dichotomised into ‘lots’ versus other responses. Finally, participants were asked how often they were ‘teased or called names’ and ‘bullied’, allowing derivation of an ‘ever teased or bullied’ variable.

Analyses

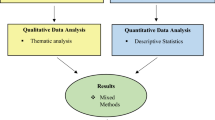

The semi-structured interviews were transcribed and pseudonyms applied, then analysed using a framework approach35 with the aid of NVivo (version 7; QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia) qualitative data analysis software. This paper focuses on participants’ responses relating to descriptions of themselves as a teenager and teenage concerns. Quantitative analyses cross-tabulated 11–16/16+ Study measures according to the concern which participants had expressed in relation to their adolescent overweight or obesity.

Results

A total of 26 participants had been obese (including 11 with BMI⩾99.6th centile) at some point in early adolescence, the remaining nine had been overweight (BMI=95th–97.9th centiles). The interviews represented a broad range of adolescent experiences. Although weight-related issues featured prominently in some, it appeared other participants would not have referred to such issues at all, had they not been specifically included in the topic guide. The language used by the participants to describe their bodies in early adolescence demonstrated that most had been aware of their overweight, but some appeared to have been more aware than others. None referred to themselves as having been obese; instead they used terms such as ‘overweight’, ‘fat’, ‘big’ or, among males only, ‘chubby’, whereas females commonly mentioned clothing sizes. Even when specifically asked about teenage health concerns, none recalled weight-related health worries. Thus, Patricia said that ‘as a teenager, even though I was heavy, I wasn’t unwell’, and Chris ‘didn’t think I was any less healthy than my friends’. Being unhealthy was equated with illness. For those without particular conditions, the consensus was ‘you just assumed you were healthy’ (Matthew).

Participants varied greatly in the degree of concern recalled about their early adolescent obesity, from major concerns impacting on much of their lives, to almost no concerns at all. We classified participants on the basis of the extent to which they described weight-related concerns. Table 1 (right-hand column) shows these were not clearly patterned by degree of early adolescent overweight or by gender. We organised our exploration of participants’ descriptions of their early teenage bodies and the impact of their body size on their lives according to how severe their adolescent obesity had been at its worst (Table 1). Detailed results in the form of relevant sections from each interview transcript can be found in the Supplementary web document, but are summarised below.

Recalled concerns among participants who had been ‘very’ (BMI⩾99.6th centile; ⩾2.66 s.d.) or ‘extremely obese’ (BMI⩾+3 s.d.)

These 11 participants were the most obese in their teenage years, including seven whose BMI had been >+3 s.d. (equivalent to BMI at age 20 of 35 kg m–2). However, five recalled no and three only minor or specific concerns about overweight, four of whom had BMI above +3 s.d. Only Elizabeth, Lisa and Colin recalled major and general concerns. Elizabeth ‘felt, like I was overweight’, believed everybody else thought this too and ‘was that mad and that sad and that angry’. But there was also ambivalence: Lisa, ‘just didn’t think much of myself […] was always concerned about my weight and size’ and wore black in a ‘just hiding myself kind of a way’, but also recalled that ‘I had a very strange body image, I thought I was a lot heavier than what I was’. For Colin, although only just in the ‘very obese’ category ‘weight has always been an issue’, and by age 15 he was making himself sick: ‘I hated the way I looked. I hated the size I was, and I just tried to do everything in my power’ (to lose weight).

However, Anne, who had been the most obese of all participants expressed only minor concern. She accepted that ‘I’ve always been overweight from a child’, was first referred to a dietician at age 3, and suggested ‘when you’re younger you think I don’t care’. Two of the males in this group, though less extremely obese also recalled minor concerns. Richard described his looks as his ‘major concern’ in his early teenage years, commenting ‘I probably coulda done wae losing maybe a stone, maybe a stone and a half—that was aboot it’, but said that ‘I wasnae that bothered aboot my weight […] I wasnae like, fat. I mean, I think there's a difference between fat and podgy. I think I was podgy’. Charlie described himself as ‘massively overweight—I was quite a bit overweight’ and weight was ‘one o’ those things … that’d get tae ye sometimes’, but as a teenager ‘I wasn’t majorly unhappy wi’ being overweight’. Finally, Geoff, one of the most obese participants, recalled ‘I wis always quite chubby’, but no teenage concerns: ‘That's who I wis, I couldnae really change that’.

The five other most obese participants, though all aware of their overweight, also recalled being largely unconcerned. Eilidh suggested that having to buy clothes in sizes up to 20 ‘just didn’t register with me, do you know there was always like excuses in your head like ‘Oh it must be small made’. Donna described standing up to teasing but recalled that ‘I was quite a carefree teenager, I didn’t really have big worries or anything’. Jenny was also ‘bullied’, but by one individual ‘and he was an idiot’ and she ‘never worried about anything’. Patricia recalled that ‘I knew a lot of people who were quite big so it was kinda more, more than just one of me and I didn’t really notice it […] I didn’t like being big and stuff […] but I mean I don’t think I was that concerned’. She also remembered people saying ‘it's all right, you’re not that heavy’.

Participants who had been obese (BMI 98th–99.5th centiles)

A similar range of concern was evident in the recollections of the 15 participants who had been, at their largest only obese; three recalled major, and six minor concerns, the remainder recalled having been unconcerned. Among the former, Catherine came from a family who were ‘all big’, was ‘scared’ by her own increasing weight and extremely upset by the weight-based teasing of one boy. Neil worried ‘all the time’ about being overweight and got ‘a hard time aff the boys’ at school, although ‘I never got any beatings, like, regularly or anything … I was too kinda big for them to kinda really want to do anything like that’. Those expressing minor concerns also described resilience: Christina's size was matched by a ‘big’ personality. Emma got ‘picked on’ at school, ‘but you’ve just gotta get on with it’; she remembered ‘I enjoyed being at school and stuff like that’. Jamie was ‘a chubby kid’ but ‘it was something that concerned me but it didn’t distress me’.

Six recalled almost no concern at all. Kirsty, the most obese in this group, recalled that ‘I don’t think I really had any concept of being big […] friends never used to mention it, and you know, I just don’t think it really registered’. Natasha, who ‘was as happy as any’, had been aware of her weight, but ‘I would never not eat anything thinking ‘Oh, I’m too fat, I can’t have this bar of chocolate’, you know?’. Similarly, Mark commented that ‘I probably didn’t like [my weight] all that much but I certainly didn’t do anything about it’. Noel knew he was ‘quite a chubby, even up to I left school I think I was aboot fifteen, fourteen and a half stone, so I was quite heavy’ but, ‘I was always happy you know it never affected me in any way’. Although not reporting experience of victimisation, Noel was involved in fights but was ‘always aw right’, partly because ‘I weighed about three stone heavier than everybody’.

Participants who had been overweight (BMI 95th–97.9th centiles)

The nine participants who had, at their largest, only been overweight (equivalent to BMI at age 20 of above 27.5 but below 30) also displayed a range of weight-related concerns, with only two recalling no concern. The most major general concerns were reported by Nina who believed that right from primary school ‘I got put into the bracket of being overweight and I kinda knew it myself so I was quite paranoid about it’. She was lonely, ‘singled out’ for ‘hassle’ from more popular pupils, ‘dreaded’ PE and ‘it was the end of the world, you know, it was guilty if I’d had a chocolate bar or whatever’. Reflecting on this period, Nina said ‘I probably thought I was more overweight than I actually was’. Similarly, Rachel had looked back ‘at pictures of me when I was thirteen, fourteen and I thought that I was quite fat and I wasn’t at all’. Her friendship group was very appearance-focused: ‘It was a big issue tae all my friends as well so I think that as a group, we all put a lot of emphasis on it from quite an early age’.

Others described less significant, more specific concerns. Laura, another who mentioned that ‘there's pictures of me and I don’t look tubby at all’, ‘hated’ the size of her ‘wee tubby belly’ and ‘boobs’. Chris, who ‘always felt I was a bit overweight’, was ‘quite concerned’, particularly about the impact of his weight on potential friendships with girls; he was also teased about it by his sister. In contrast, Clare recalled no concerns: ‘it was like not in my mind at all’.

Comparison with earlier 11–16/16+ survey responses

How were recalled early adolescent weight-related concerns associated with weight- health- and peer-related survey responses obtained from this qualitative sample at ages 11, 13 and 15? Table 2 cross-tabulates these prior measures according to whether participants expressed any (major/minor) or no concerns in relation to their adolescent overweight or obesity. Among males, those recalling concerns had earlier reported more worry about putting on weight, had lower self-esteem, fewer friends and experienced more victimisation (few differences attained statistical significance, but numbers are very small). No such pattern was seen among females apart from a suggestion that those categorised as recalling weight-related concerns had fewer friends at age 11.

Discussion

This paper drew on retrospective accounts, commonly used in qualitative interviews, particularly in studies following an oral history or narrative methodology. The young adult sample ranged from those who had been barely above a healthy weight to the extremely obese. Participants demonstrated considerable variations in recalled early adolescent weight-related awareness and concerns, and in the vast majority of cases, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to tell the severity of their adolescent overweight from a reading of their interview transcript. This is consistent with quantitative studies, which show that although levels of body dissatisfaction and weight-related concerns increase with increasing BMI, it is not the case that every overweight or obese child or adolescent is dissatisfied or concerned.14, 15, 16

As adolescents, this group seemed to have been aware of their overweight, but not all were concerned about it. Lack of concern was particularly evident in relation to the impact of obesity on health. There is evidence that overweight or obese adolescents are more likely to underestimate their size if parents and school-friends are also overweight or obese,16 and a growing body of literature has suggested that the increased prevalence of obesity has led to it becoming normalised.8 The media may also have an impact on body size awareness. Studies linking the media with (particularly female) body dissatisfaction have been generally focused on the impact which images of thin models and actresses have on desires to be thin.36 However, obesity-related media items tend to be illustrated with images of the ‘super obese’ and so may contribute to decreased awareness or concern among those with lower (more ‘normal’) obesity levels.

Given the importance of peer acceptance in adolescence,37 it is perhaps no surprise that a key issue in relation to recalled concerns was peers’ reactions. In our study, there were several reports suggesting that the peer group offered reassurance about the unimportance of overweight, together with evidence of the opposite. Although many recalled verbal bullying and a smaller number loneliness, others spoke of belonging to strong supportive friendship groups within which their body size was not an issue. Indeed, some males mentioned that overweight had protected against physical bullying and gave an advantage in a fight.

Friendships established in early childhood, a ‘good personality’, sense of humour and ability to ignore teasing, in addition to athletic ability or money were found in one qualitative study to affect the views of ‘average weight’ 11–15-year old Americans about their overweight peers.19 Another qualitative study of 15–17-year old Australians found body-related messages from peers, family and media could be distorted by respondents’ ‘internal dialogue’; thus, although some seemed able to brush-off comments, others could interpret even positive messages as critical.38 It may be that in our study those who reported greater concern were displaying ‘negative affectivity’, a dispositional style associated with distress and anxiety39 and this may explain why some in the overweight group experienced such distress about quite mild overweight, whereas some of the most obese were unconcerned. This method of coping with stigmatisation protects self-esteem by shifting the focus away from personal characteristics;40 there is also evidence that self-esteem is higher among children who believe they are not responsible for their overweight.20

These data were gathered from young adults in respect of experiences which occurred around 10 years before, when they were in early adolescence, and there is debate as to the accuracy of retrospective accounts. However, studies that have compared recalled information with official records have found reasonable validity, although accuracy may be better for data or facts rather than emotional events41 and vary according to what has happened since the event recalled and the emotional state of the individual at the time of recall.42 Participants might have been providing ‘public’ accounts which they viewed as acceptable to an academic from a medical research unit43 or striving to present their teenage lives as ‘normal’ and unaffected by their body size.44 On the other hand, the retrospective approach allowed interviewees to reflect on past experiences at a time of greater maturity and without the confusion of other events occurring at the same time, thus allowing for a clearer understanding of those experiences.45 We cannot know how far these accounts of early adolescent experiences reflect ‘the truth’, any more than we can be sure that responses made to the 11–16/16+ Study questionnaires at 11, 13 and 15 did so.46 It is interesting that although males categorised via their young adult interview data as recalling more concerns had reported more weight-worries, peer-related difficulties and lower self-esteem in early adolescence, there was almost no correspondence between the recalled experiences and early adolescent responses among females. Although the numbers are too small for generalisation, this may reflect generally greater weight- and appearance-related concerns among females, irrespective of actual overweight.38, 47

Childhood and adolescent obesity is generally perceived as a condition that causes much unhappiness, with suggestions that highlighting it might worsen distress.48 However, our findings, similar to earlier quantitative studies,14, 15, 16 suggest instead that some extremely obese adolescents may not be particularly concerned about overweight, even if aware, whereas other young people, with quite trivial degrees of overweight are very distressed by it. Those who are unaware of the extent of their obesity, or who are aware but not concerned are unlikely to adopt weight-loss behaviours.2 As teenage obesity tends to track into adulthood,3, 4 increasing levels of obesity in adolescents are a major public health issue. Evidence that obesity-related behaviours also show tracking, highlights the importance of developing obesity-related interventions in childhood.5 It is now clear that professionally administered weight-loss interventions pose minimal risks of precipitating eating disorders in overweight children and adolescents49 and newer more behaviourally and family-centred interventions have shown good results. However, there is a tricky balance between raising awareness and concern amongst the most obese adolescents to levels sufficient to trigger individual behavioural change, without also generating distress or promoting stigmatisation.

References

Dietz WH . Reversing the tide of obesity. Lancet 2011; 378: 744–746.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC . Common processes of change for smoking, weight control, and psychological distress. In: Shiffman S, Wills T (eds). Coping and Substance Abuse. Academic Press: New York, 1985, pp 345–364.

Power C, Laker S, Cole TJ . Measurement and long-term health risks of child and adolescent fatness. Int J Obes 1997; 21: 507–526.

Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ . Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev 2008; 9: 474–488.

Craigie AM, Lake AA, Kelly SA, Adamson AJ, Mathers JC . Tracking of obesity-related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: a systematic review. Maturitas 2011; 70: 266–284.

Lobstein T, Baur LA, Uauy R . Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. Obes Rev 2004; 5 (Suppl. 1): 4–85.

Reilly JJ . Descriptive epidemiology and health consequences of childhood obesity. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 19: 327–341.

Wardle J, Haase AM, Steptoe A . Body image and weight control in young adults: international comparisons in university students from 22 countries. Int J Obes 2006; 30: 644–651.

Latner JD, Stunkard AJ . Getting worse: The stigmatization of obese children. Obes Res 2003; 11: 452–456.

Wardle J, Cooke L . The impact of obesity on psychological well-being. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 19: 421–440.

Ricciardelli LA, McCabe MP . Children's body image concerns and eating disturbance: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev 2001; 21: 325–344.

French S, Story M, Perry C . Self-esteem and obesity in children and adolescents: a literature review. Obes Res 1995; 3: 479–490.

Cornette R . The emotional impact of obesity on children. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2008; 5: 136–141.

Jansen W, van de Looij-Jansen PMV, de Wilde EJ, Brug J . Feeling fat rather than being fat may be associated with psychological well-being in young Dutch adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2008; 42: 128–136.

Viner RM, Haines MM, Taylor SJC, Head J, Booy R, Stansfeld S . Body mass, weight control behaviours, weight perception and emotional well being in a multiethnic sample of early adolescents. Int J Obes 2006; 30: 1514–1521.

Maximova K, McGrath JJ, Barnett T, O’Loughlin J, Paradis G, Lambert M . Do you see what I see? Weight status misperception and exposure to obesity among children and adolescents. Int J Obes 2008; 32: 1008–1015.

Kaliala-Heino R, Kautiainen S, Virtanen S, Rimpela A, Rimpela M . Has the adolescents’ weight concern increased over 20 years? Eur J Public Health 2003; 13: 4–10.

Johnson F, Cooke L, Croker H, Wardle J . Changing perceptions of weight in Great Britain: comparison of two population surveys. Br Med J 2008; 337: a494.

Hoerr SL, Kalen D, Kwantes M . Peer acceptance of obese youth: a way to improve weight control efforts? Ecol Food Nutr 1995; 33: 203–213.

Walsh Pierce J, Wardle J . Cause and effect beliefs and self-esteem of overweight children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1997; 38: 645–650.

Murtagh J, Dixey R, Rudolf M . A qualitative investigation into the levers and barriers to weight loss in children: opinions of obese children. Arch Dis Child 2006; 91: 920–923.

Smith MJ, Perkins K . Attending to the voice of adolescents who are overweight to promote mental health. Arch Psychiatric Nurs 2008; 22: 391–393.

Snethen JA, Broome ME . Weight, exercise and health: children's perceptions. Clin Nurs Res 2007; 16: 138–152.

Lieberman A, Robbins JM, Terras A . Why some adolescents lose weight and others do not: a qualitative study. J Natl Med Assoc 2009; 101: 439–447.

Wills W, Backett-Milburn K, Gregory S, Lawton J . Young teenagers’ perceptions of their own and others’ bodies: A qualitative study of obese, overweight and ‘normal’ weight young people in Scotland. Soc Sci Med 2006; 62: 396–406.

Rees R, Oliver K, Woodman J, Thomas J . Children's Views About Obesity, Body Size, Shape and Weight: a Systematic Review. EPPI Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London: London, 2009.

Smith E . Bothered enough to change? A qualitative investigation of recalled adolescent experiences of obesity. PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, 2010.

West P, Sweeting H, Speed E . We really do know what you do: a comparison of reports from 11 year olds and their parents in respect of parental economic activity and occupation. Sociology 2001; 35: 539–559.

Cole TJ, Freeman JV, Preece MA . Body mass index reference curves for the UK, 1990. Arch Dis Child 1995; 73: 25–29.

Gray CM, Lorimer K, Anderson AS, Benzeval M, Hunt K, Wyke S . What's in a Word? Response to weight status terminology and motivation to lose weight. Eur J Public Health 2009; 19 (S1): 66.

Brener ND, Eaton DK, Lowry R, McManus T . The association between weight perception and BMI among high school students. Obes Res 2004; 12: 1866–1874.

Standley R, Sullivan V, Wardle J . Self-perceived weight in adolescents: over-estimation or under-estimation? Body Image 2009; 6: 56–59.

NICE. Obesity: the Prevention, Identification, Assessment and Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults and Children. (Section 2: Identification and Classification). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: London, 2006.

Rosenberg M . Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 1965.

Ritchie J, Spencer L, O’Connor W . Carrying out qualitative analysis. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J (eds). Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. Sage Publications: London, 2003.

Monro F, Huon G . Media-portrayed idealized images, body shame, and appearance anxiety. Int J Eat Disord 2005; 38: 85–90.

Hendry LB, Glendinning A, Shucksmith J . Adolescent focal theories: age-trends in developmental transitions. J Adolesc 1996; 19: 307–320.

McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA, Ridge D . “Who thinks I need a perfect body?” Perceptions and internal dialogue among adolescents about thier bodies. Sex Roles 2006; 55: 409–419.

Watson D, Clark LA . Negative Affectivity: The Disposition to Experience Aversive Emotional States. Psychol Bull 1984; 96: 465–490.

Puhl R, Brownell KD . Ways of coping with obesity stigma: review and conceptual analysis. Eat Behav 2003; 4: 53–78.

Blane DB . Collecting retrospective data: Development of a reliable method and a pilot study of its use. Soc Sci Med 1996; 42: 751–757.

Hardt J, Rutter M . Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004; 45: 260–273.

Cornwell J . Hard-earned Lives: Accounts of health and illness from East London. Tavistock Publications: London, 1984.

Goffman E . Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Doubleday Anchor Books: New York, 1959.

Atkinson RL . The Life Story Interview: Context and Method. In: Gubrium JF, Holstein JA (eds). Handbook of Interview Research. Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2002.

Hammersley M, Gomm R . Bias in Social Research. Sociol Res Online 1997; 2. http://www.socresonline.org.uk/2/1/2.html.

Sweeting H, West P . Gender differences in weight related concerns in early to late adolecence. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002; 56: 70–701.

O’Dea JA . Prevention of child obesity: ‘First, do no harm’. Health Educ Res 2005; 20: 259–265.

Butryn ML, Wadden TA . Treatment of overweight in children and adolescents: Does dieting increase the risk of eating disorders? Int J Eat Disord 2005; 37: 285–293.

Acknowledgements

ES was funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) on a PhD studentship. HS is funded by the MRC as part of the Gender and Health Programme (WBS U.1300.00.004) at the Social and Public Health Sciences Unit. CW is funded by Glasgow University and NHS Greater Glasgow. We would like to thank Sally Macintyre and Kate Hunt for comments on an earlier version. We also thank the young people, nurse interviewers, schools and all those from the MRC Social and Public Health Sciences Unit involved in the West of Scotland 11–16/16+ Study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on International Journal of Obesity website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, E., Sweeting, H. & Wright, C. ‘Do I care?’ Young adults' recalled experiences of early adolescent overweight and obesity: a qualitative study. Int J Obes 37, 303–308 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2012.40

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2012.40