Abstract

Purpose:

With the accelerated implementation of genomic medicine, health-care providers will depend heavily on professional guidelines and recommendations. Because genomics affects many diseases across the life span, no single professional group covers the entirety of this rapidly developing field.

Methods:

To pursue a discussion of the minimal elements needed to develop evidence-based guidelines in genomics, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Cancer Institute jointly held a workshop to engage representatives from 35 organizations with interest in genomics (13 of which make recommendations). The workshop explored methods used in evidence synthesis and guideline development and initiated a dialogue to compare these methods and to assess whether they are consistent with the Institute of Medicine report “Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust.”

Results:

The participating organizations that develop guidelines or recommendations all had policies to manage guideline development and group membership, and processes to address conflicts of interests. However, there was wide variation in the reliance on external reviews, regular updating of recommendations, and use of systematic reviews to assess the strength of scientific evidence.

Conclusion:

Ongoing efforts are required to establish criteria for guideline development in genomic medicine as proposed by the Institute of Medicine.

Genet Med advance online publication 19 June 2014

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The promise of genomics in precision health care is rapidly becoming a reality in today’s health-care landscape. The use of next-generation sequencing is an emerging feature in clinical practice, especially in the diagnosis of rare genetic diseases.1 In addition, several “omic” technologies promise to provide more targeted treatment and prevention.2 Several academic medical centers and integrated health systems have proposed or launched programs integrating genomic medicine into clinical care. In this time of rapid implementation of genomic medicine, clinicians will increasingly depend on professional guidelines and recommendations about how to incorporate genomic technologies into clinical practice.

In 2011, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released its report “Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust” to help standardize how professional societies develop and report high-quality clinical guidelines and to ease the burden on health-care providers of determining which guidelines to follow.3 The report specified key components that need to be incorporated into the process of developing evidence-based guidelines (e.g., recommendations). The components included the establishment of evidence foundations (i.e., use of evidence versus expert opinion), management of conflicts of interest, incorporation of an external review, and continuous updating of guidelines as new evidence becomes available.

Several organizations perform systematic reviews of the literature and develop guidelines or recommendations for the use of genomic technologies (e.g., applications that are based on DNA, gene expression, and RNA).4,5,6 Because genomic technologies have the potential to influence many areas of health care, professional societies and guideline developers will increasingly be making recommendations about genomic applications; however, it is often unclear how various groups review evidence and develop guidelines for genomic applications. In 2005, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launched the Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention Working Group5 to develop a model process for the evaluation of genomic tests and other applications in transition from research to practice. For each clinical scenario, the Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention Working Group uses a framework that evaluates analytic validity, clinical validity, clinical utility, and associated ethical, legal, and social implications (ACCE Framework).6 Other systems, such as the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach,7 hone in on types of outcomes in determining these measures.7,8 Identifying differences in evaluation approaches between various systems and groups may be a first step toward methods harmonization.

Because no single recommending group covers the entirety of the field of genomics, it will be important to achieve a broad-based consensus on the minimum elements needed for evidence synthesis and guideline development in genomics. Toward this objective, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Office of Public Health Genomics and the National Cancer Institute’s Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences held a workshop, “Comparing, Contrasting, and Demystifying Methods for Knowledge Synthesis and Evidence-Based Guideline Development in Genomic Medicine,” in March 2013. The aim of the workshop was to engage representatives from a broad range of groups with interest in clinical guidelines and to discuss the methods used in knowledge synthesis and evidence-based guideline development. Moreover, the workshop initiated a dialogue to compare these methods and to assess whether the existing approaches are consistent with the recommendations proposed in the IOM report.4 The current article synthesizes the information gathered from the workshop’s materials and discussions.

Methods

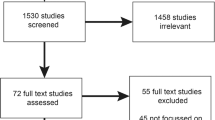

The workshop included representatives from 35 organizations, 13 of which make genomic guidelines or recommendations (Supplementary Table S1 online).

Before their participation in the workshop, representatives from nine organizations were asked to respond to eight questions on behalf of their organization. Seven key components of guideline development derived from the IOM report framed the basis for the open-ended questions (Supplementary Table S2 online ). The objective was to gather information relating to the process of evidence-based guideline development. We compiled relevant information from the responses of the representatives ( Table 1 ; Supplementary Table S3 online). The full summary was shared with the participants before the meeting to facilitate discussion during the workshop.

The format of the workshop included presentations and group discussions. The presentations primarily focused on methods and conceptual frameworks used by various groups in formulating evidence-based guidelines and recommendations and included information about how and why the methods have evolved. Following presentations, there was a group discussion on similarities and differences in methods and processes for rating quality, confidence in the results, and magnitude of evidence.

Summary of Assessment and Workshop Discussions

Eight organizations that recommend genomic applications for use in clinical practice or coverage by insurers responded to the open-ended questions (summary in Table 1 ). Five of these eight (the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium, Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention Working Group, Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group, National Society of Genetic Counselors, and American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics) engage in guideline development relating to genetic or genomic applications; two (the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American Society of Clinical Oncologists) focus on developing guidelines relevant to cancer and cancer risk; and one (Blue Cross Blue Shield Association) assesses medical technologies. The target audiences across all organizations are specific professionals corresponding to the organization’s field focus (e.g., oncologists for the American Society of Clinical Oncologists or clinicians interested in pharmacogenomic testing for the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium).

Overall, all eight organizations share core components that are integral to their respective guideline/recommendation development process. All have written policies to address group membership and to identify, prevent, and manage conflicts of interests. External review of recommendations/guidelines exists in all organizations. The use of systematic reviews to assess the strength of scientific evidence varies widely across the organizations, as do factors involved in assessing the robustness of the scientific evidence.

Each organization strives to ensure that the composition of its committee developing a specific guideline is multidisciplinary whenever possible. Many organizations work to balance the composition between content and methods experts specific to the topic under review. Identification of membership can be achieved via peer recommendations or through active recruitment of individuals with proven leadership and expertise in the field. Some organizations require that at least one representative on each committee be from the patient community.

Disclosure of conflicts of interest is mandatory across all organizations; however, the degree of acceptable conflicts of interest varies. The American Society of Clinical Oncologists, for example, stipulates that less than 50% of a guideline panel members, including the panel chair, may have conflicts of interest. Conversely, the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics discloses that in case of rare diseases, conflicts of interest may be unavoidable and expert members may have commercial relationships to the genetic test they were tasked with evaluating; however, they commit to transparency and these conflicts are disclosed in any publication related to the guideline.

The use of systematic reviews to assess the robustness of the scientific evidence varies considerably across the organizations. The IOM report specifically defines systematic reviews as those that meet standards set by the IOM’s Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research.3 It is likely that some participating organizations may not necessarily comply with all elements of the IOM definition for systematic reviews, as in some cases systematic reviews may not be comprehensive enough to accurately summarize the field.

As anticipated, how the organizations rank the quality of evidence varies depending on the topic of focus. Some organizations appraise the quality of the evidence based on several factors, including the study design (e.g., randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and prospective cohort studies), the consistency of the estimated effects (i.e., heterogeneity), and the sample sizes. What constitutes a high level of evidence also varies between the organizations. For example, the gold standards of the American Society of Clinical Oncologists differ depending on the type of guideline being considered: for therapeutic guidelines, an RCT or meta-analysis of RCTs is considered top tier, whereas prospective cohort studies or retrospective analyses with identifiable control groups are used for prognostic guidelines. The Blue Cross Blue Shield Association and the Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention Working Group require recommended technologies to demonstrate analytic validity, clinical validity, and clinical utility, and preferred study designs can differ for each of these evaluation components.5

Some organizations categorize the level of evidence based on the consensus of the group, whereas others use systematic review in conjunction with expert review. Although all organizations have some form of an external review process, the processes vary between organizations. External reviews of guidelines may either be arranged internally or rely on peer reviews via journal submission, which acts as a surrogate for external review. The groups also vary widely in their approach to updating recommendations. Some groups have a systematic approach to revisit and update guidelines, whereas others rely on topics coming from members before updating.

Discussion

We convened the workshop to address an emerging need in the integration of genomics into clinical medicine. The workshop’s primary purpose was to discuss the minimal elements needed to synthesize and develop evidence-based guidelines for genomic applications. There is particular urgency to enhance high-quality guideline development in genomic medicine, which is underscored by the rapid growth in the number of genomic applications that are clinically available. Recently, Clyne et al.9 showed that in 1 year (May 2012–April 2013), 45 clinical guidelines, policies, and recommendations were published for genomic applications (7 not published in PubMed). Comparisons of specific genomic guidelines using the AGREE II instrument,10 as well as a recent review of grading systems used in the evaluation of genomic tests,11 highlight the fact that there are no universal principles shared by organizations evaluating genomic applications.

The IOM report3 specified key components that should be incorporated into the process of developing evidence-based guidelines/recommendations. When these processes were compared with the IOM report recommendations, the organizations that participated in the workshop agreed that the components that are integral to guideline/recommendation development are to establish policies to manage group membership and to identify, prevent, and manage conflicts of interest. However, the level of external review, updating of recommendations, and the use of systematic review to assess the strength of scientific evidence varied widely across the organizations. It should be noted that a group’s ability to perform detailed systematic reviews may depend on the group’s size and resources. However, some groups, such as the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, are now considering how their guideline development process could be more in line with the IOM report.

Guidelines from some organizations, such as the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium and Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group, assume that the genetic test information is already available and gear their recommendations toward how to use genomic information, not whether to order genetic tests.12 The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics has recently addressed this topic by putting forward a set of recommendations for the return of incidental findings in the setting of clinical whole-genome/whole-exome sequencing.13 In addition, the National Institutes of Health is funding the Clinical Variant resource (ClinVar14) and the clinically relevant genomics consortium (ClinGen) to develop standardized processes by which genomic variants are determined to be clinically relevant and actionable.15

Given the rapidly changing landscape in genomic medicine, we may need more nimble methods and approaches to evidence-based guideline development than those currently used in other fields. For example, professional groups developing guidelines and recommendations could collaborate on a periodic basis and better leverage prior efforts in order to minimize the possibility of reinventing guidelines from scratch. Given their labor-intensive nature, systematic reviews could be conducted in a more coordinated manner. Groups could deposit systematic review data into the established Systematic Review Data Repository of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which could facilitate updating genomic-based recommendations more quickly.16 The application of systematic, but rapid, methodologies may also be explored.17 Groups such as the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium and the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group could coordinate much of their evidence review using annotation tools provided by the Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base.18

Professional groups should also continue the dialogue on balancing the need for evidence from observational studies versus RCTs. Observational evidence is frequently necessary, and RCTs are often not feasible, particularly in the case of rare diseases. Nevertheless, the need for RCTs may be unavoidable for some applications, a subject worthy of additional conversation.19 Guideline developers will also need to consider the use of modeling to fill evidence gaps.20

As is true for many clinical practice areas, and given the nascent state of the field, the process of guideline development in genomic medicine is unlikely to be entirely consistent with the IOM recommendations. Although one size does not fit all, and genomics may not be currently able to meet all of the IOM report’s requirements, genomic guideline developers should strive to incorporate as many of the IOM report recommendations as possible for successful evidence-based implementation of genomic medicine in practice.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Berg JS, Amendola LM, Eng C, et al.; Members of the CSER Actionability and Return of Results Working Group. Processes and preliminary outputs for identification of actionable genes as incidental findings in genomic sequence data in the Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research Consortium. Genet Med 2013;15:860–867.

GAPP Finder. http://www.hugenavigator.net/GAPPKB/topicStartPage.do. Accessed 17 December 2013.

Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2011.

Gudgeon JM, McClain MR, Palomaki GE, Williams MS . Rapid ACCE: experience with a rapid and structured approach for evaluating gene-based testing. Genet Med 2007;9:473–478.

Teutsch SM, Bradley LA, Palomaki GE, et al.; EGAPP Working Group. The Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Initiative: methods of the EGAPP Working Group. Genet Med 2009;11:3–14.

Haddow JE, Palomaki GE . ACCE: a model process for evaluating data on emerging genetic tests. In: Khoury MJ, Little J, Burke W (eds). Human Genome Epidemiology. Oxford University Press: New York, 2004:217–233.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al.; GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–926.

Veenstra DL, Piper M, Haddow JE, et al. Improving the efficiency and relevance of evidence-based recommendations in the era of whole-genome sequencing: an EGAPP methods update. Genet Med 2013;15:14–24.

Clyne M, Schully SD, Dotson D, et al. Horizon scanning for translational genomic research beyond bench to bedside. Genet Med 2014;16:535–538.

Simone B, De Feo E, Nicolotti N, Ricciardi W, Boccia S . Methodological quality of English-language genetic guidelines on hereditary breast-cancer screening and management: an evaluation using the AGREE instrument. BMC Med 2012;10:143.

Gopalakrishna G, Langendam MW, Scholten RJ, Bossuyt PM, Leeflang MM . Guidelines for guideline developers: a systematic review of grading systems for medical tests. Implement Sci 2013;8:78.

Caudle KE, Klein TE, Hoffman JM, et al. Incorporation of pharmacogenomics into routine clinical practice: the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline development process. Curr Drug Metab 2014;15:209–217.

Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, et al.; American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med 2013;15:565–574.

Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Riley GR, et al. ClinVar: public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res 2014;42(Database issue):D980–D985.

Ramos EM, Din-Lovinescu C, Berg JS, et al. Characterizing genetic variants for clinical action. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2014;166C:93–104.

Systematic Review Data Repository (SRDR). http://srdr.ahrq.gov/. Accessed 17 December 2013.

Flockhart DA, O’Kane D, Williams MS, et al.; ACMG Working Group on Pharmacogenetic Testing of CYP2C9, VKORC1 Alleles for Warfarin Use. Pharmacogenetic testing of CYP2C9 and VKORC1 alleles for warfarin. Genet Med 2008;10:139–150.

Whirl-Carrillo M, McDonagh EM, Hebert JM, et al. Pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2012;92:414–417.

Ioannidis JP, Khoury MJ . Are randomized trials obsolete or more important than ever in the genomic era? Genome Med 2013;5:32.

Carvajal-Carmona LG, Zauber AG, Jones AM, et al.; APC Trial Collaborators; APPROVe Trial Collaborators; CORGI Study Collaborators; Colon Cancer Family Registry Collaborators; CGEMS Collaborators. Much of the genetic risk of colorectal cancer is likely to be mediated through susceptibility to adenomas. Gastroenterology 2013;144:53–55.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all of the workshop participants, who fully engaged in the meeting discussions. In addition, the work presented here was partially supported by National Institutes of Health grants R24GM61374, U01GM 92666, and U01HL 105198. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table S1

(DOC 37 kb)

Supplementary Table S2

(DOC 31 kb)

Supplementary Table S3

(DOC 85 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schully, S., Lam, T., Dotson, W. et al. Evidence synthesis and guideline development in genomic medicine: current status and future prospects. Genet Med 17, 63–67 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2014.69

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2014.69