Abstract

Purpose:

To overcome literacy-related barriers in the collection of electronic family health histories, we developed an animated Virtual Counselor for Knowing your Family History, or VICKY. This study examined the acceptability and accuracy of using VICKY to collect family histories from underserved patients as compared with My Family Health Portrait (MFHP).

Methods:

Participants were recruited from a patient registry at a safety net hospital and randomized to use either VICKY or MFHP. Accuracy was determined by comparing tool-collected histories with those obtained by a genetic counselor.

Results:

A total of 70 participants completed this study. Participants rated VICKY as easy to use (91%) and easy to follow (92%), would recommend VICKY to others (83%), and were highly satisfied (77%). VICKY identified 86% of first-degree relatives and 42% of second-degree relatives; combined accuracy was 55%. As compared with MFHP, VICKY identified a greater number of health conditions overall (49% with VICKY vs. 31% with MFHP; incidence rate ratio (IRR): 1.59; 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 1.13–2.25; P = 0.008), in particular, hypertension (47 vs. 15%; IRR: 3.18; 95% CI: 1.66–6.10; P = 0.001) and type 2 diabetes (54 vs. 22%; IRR: 2.47; 95% CI: 1.33–4.60; P = 0.004).

Conclusion:

These results demonstrate that technological support for documenting family history risks can be highly accepted, feasible, and effective.

Genet Med 17 10, 822–830.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The family health history is one of the most important risk factors for many chronic conditions, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer, and represents an integration of disease risk stemming from genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors.1,2,3 When compared with genotypic information, family history remains a strong independent risk factor for disease.4,5 As such, family history assessment remains the current gold standard for clinical risk assessment2,6,7 and is considered a genomic tool and proxy for genetic predisposition that can serve as a means to better guide and personalize medical care and disease prevention.1,5,8,9

Although the importance of family health history is evident, the collection of family history information by patients and the integration of family history assessment into clinical practice has had surprisingly poor frequency and quality.10 Numerous barriers preclude the systematic documentation of family history in primary-care settings.11 The most commonly documented barriers include lack of time, lack of physician compensation for the efforts, physicians’ lack of knowledge and skills, and other logical barriers such as lack of standardized family history collection methods.9,10,12,13 Even when family history is collected in primary care, it is often lacking in quality or detail that would yield useful information about disease risk.10,12

Because of the importance of family history assessment and its lack of systematic documentation, several national efforts have been undertaken to improve the documentation and use of family history, particularly in primary-care settings.1,3 Yet, in spite of these national efforts to promote family history tools, concerns about the appropriateness of these tools for underserved populations with low literacy rates have been raised.14 Health literacy has been defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”15 Approximately half of US adults have limited health literacy, which disproportionally affects those who are less educated, elderly, poor, or minorities or who have limited English proficiency.16,17,18 Although computer-based family history tools have been developed with the goal of increasing genetic literacy,1 there is evidence to suggest that existing tools may be challenging to use for a large portion of the US population.14

In efforts to overcome the aforementioned barriers, we developed a relational agent, or “virtual counselor,” to collect family health history information. Relational agents are computer-animated characters that use speech, gaze, hand gesture, prosody, and other nonverbal modalities to emulate the experience of human face-to-face conversation. They can be programmed and used for automated health education and behavioral counseling interventions, and they have been demonstrated to establish and maintain therapeutic relationships through these and other interactions.19 These agents have been successfully used to facilitate medication adherence,20 to explain health documents,21,22 to promote breastfeeding,23 and to educate about and motivate exercise and weight loss.24,25,26,27 Use of the relational agent system requires minimal reading skills. We previously showed that the interface can be designed in a manner that is usable for people with limited health literacy, limited reading capacity, and no prior computer experience,19,22,28,29 which makes it a potentially useful platform for collecting detailed family history information in an electronic format.

We developed a prototype virtual counselor that we named VICKY (Virtual Counselor for Knowing Your Family History; Figure 1 ). VICKY is an animated computer character designed to collect family health history information by asking a series of questions about the user’s family health history, targeting common chronic conditions including heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, and various cancers. Users respond to VICKY’s verbal questions by selecting a preformulated simple response on a touch screen, with the choices updated at each turn in the conversation. Response options are short and easy to read. Minimal reading and typing are required, thus reducing the literacy burden. Moreover, additional opportunities are interwoven throughout the program to let respondents tell VICKY when they are uncertain about the meaning of a response option. For example, as shown in Figure 1 , there is a response option indicating “not sure what these problems are.” Subsequent screens have VICKY asking whether they would like information about a health problem. Selected options then are verbally explained to the participant, rather than presenting an explanation or definition in text format on the screen. VICKY was deployed on a touch-screen tablet computer, interleaving her interview with displays of the patient’s family history pedigree chart as it is incrementally constructed.

The relational agent used within the VICKY program was developed and evaluated on several prior automated health counseling interventions.19,22 The dialogue content written specifically for VICKY was developed by experts in computer science, health communication, health literacy, and genetic counseling and was extensively tested by developers and research assistants (RAs) using family test cases to check for errors in flow, logic, and completeness. In addition, user testing interviews were conducted with 10 patients to identify further problematic areas to be fixed before the study. During user testing interviews, participants were instructed to use the tool and asked to “think aloud” as they were using the VICKY program. RAs observed participants as they were using the tool and documented areas that caused confusion and errors in data entry. Participants also were asked about their general experience with VICKY via a series of both open- and closed-ended questions. Results from the user testing were used to update our prototype, which we then subsequently evaluated in a pilot study.

This article reports the results from the pilot study. It specifically examines the feasibility of using VICKY to collect family health history information within an underserved patient population. The acceptability of the program was evaluated during an interview process. Accuracy of the information collected was determined by comparing family health histories collected by VICKY with those generated independently by a certified genetic counselor (gold standard). In addition, as part of our study, we randomized patients to use either VICKY or another computer-based tool that has been widely promoted (Surgeon General’s My Family Health Portrait (MFHP); https://familyhistory.hhs.gov/) to compare the acceptability and accuracy of VICKY with that of an existing tool.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Patients were recruited from the ReSPECT Registry, a recruitment services program that provides support to research investigators at Boston Medical Center (BMC). BMC is the largest safety net hospital in New England. Approximately 73% of BMC patients come from underserved populations, including low-income families, elders, people with disabilities, and immigrants. Individuals are recruited to the ReSPECT Registry from various BMC and community venues, as well as by online advertisements that link directly to the registry website.

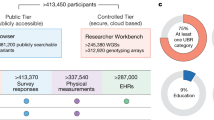

Participants were eligible for this study if they were 18 years or older, could read and write in English, and were currently or had ever been a patient at BMC. The registry staff contacted eligible participants via e-mail, letter, or telephone and provided a brief summary of the study and asked whether they would be interested in participating. A list of registry members who were interested in participating was provided to the study RA, who called to confirm study eligibility and extend an invitation to participate in the study. An appointment was subsequently scheduled for those agreeing to participate. The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram for this study is presented in Figure 2 .

Procedures

All participant interviews took place at BMC with a trained RA. Following the consent process, participants were randomized to use either VICKY or MFHP and instructed to use the tool to enter their family health history information. Because the study evaluated the usability of the stand-alone tools, participants were not provided with additional assistance or guidance to understand the tool instructions or complete their histories. Participants were provided with as much time as necessary to complete this process; most participants completed this step within 15–30 min. Following the interaction with VICKY or MFHP, participants were interviewed in person by the RA to obtain detailed feedback about their experiences with the tool. Participants were then interviewed by a genetic counselor over the telephone to obtain a detailed family health history. The genetic counselor was blind to the study arm and followed a general script for the interview, which emphasized the collection of information for common chronic conditions. A single genetic counselor conducted all the interviews and created a “gold standard” pedigree for each participant, generated in Progeny (http://www.progenygenetics.com/). All pedigree information was based solely on participant self-report. Participants received a $20 gift card for their time. In addition, participants were offered a copy of their family history pedigree, which they could receive in the mail within 1–2 weeks of participation.

Study measures

Demographics. Standard demographic information collected for all participants included age, sex, education, race/ethnicity, and income.

Computer experience. Participants were asked, “How much experience do you have with computers?” and responded by selecting either “I’ve never used one,” “I’ve tried one a few times,” I use one regularly,” or “I’m an expert.” They also rated their computer skills on a scale from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent).

Tool evaluation. Likert-scale questions were used to obtain general feedback about the family health history tools. Questions were answered on a 5-point scale (not at all to very) and included “How easy was it to use the tool?,” “How easy was it to follow the flow of the tool?,” “How easy was it to understand the information being asked?,” “How much do you like this tool?,” “How likely are you to use this tool on your own?,” “Would you recommend this tool to others?,” and “Overall, how satisfied are you with this tool?” Percentage of endorsement or agreement for each item was derived from those responding with either a 4 or 5 on the 5-point scale. In addition, a single item also asked “Overall, how would you rate the quality of the family history tool?” (5-point scale, poor/fair/good/very good/excellent).

Health literacy. The Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine tool was used to assess health literacy.30,31 The Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine tool includes a list of 66 medical words that participants are instructed to read. A reading grade equivalent is determined based on the number of words pronounced correctly.

Accuracy: family members identified. Using the pedigree generated by the genetic counselor as the gold standard, the number and relationship of family members identified by the computer tools were compared with those of family members identified by the genetic counselor. Accuracy rates were calculated by dividing the number of tool-identified relatives by the number identified by the genetic counselor and were derived for first-degree relatives, second-degree relatives, and combined total first- and second-degree relatives.

Accuracy: health conditions identified. The accuracy of health conditions identified was derived by calculating sensitivity estimates for first- and second-degree (and total) relatives for each health condition. Sensitivity, or the true-positive rate, was defined as the disease cases reported in a tool that were also identified by the genetic counselor (true positive) divided by the disease cases not captured by the tool but captured by the genetic counselor (false negatives) plus the true positives. The health conditions assessed included heart disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke, hypertension, and cancers of the breast and colon.

Analytic plan

Descriptive statistics were used to compute means and SDs for continuous variables and counts with percentages for categorical variables. A series of bivariate analyses were used to examine the effectiveness of the randomization by comparing and testing distributions of baseline variables by intervention arm using cross-tabulation with χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. Any lack of balance of these variables between the two groups was addressed by including these variables as covariates in multivariable analyses. Study arms were compared on percentage endorsement of the tool evaluation items using multivariable logistic regression. Multivariable Poisson regression models were used to examine the effect of study arm on identification of relatives and health conditions. Rate ratios illustrating relative differences in accuracy and their 95% confidence intervals were computed from these models to compare the study arms. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Analyses were conducted using two-sided tests, and a P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant demographics

A total of 74 individuals were enrolled in the study, with 70 individuals completing the protocol ( Figure 2 ). Four individuals were dropped from the study analyses because of technical issues wherein pedigrees generated from the tools (n = 3 for VICKY and n = 1 for MFHP) were not saved. Among the 70 individuals who completed the protocol, the majority were age 45 or older (74%), 60% were female, and 63% were African American ( Table 1 ). Over half of the study population (51%) had the equivalent of a high school education or less, and 60% had a household income of $25,000 or less per year. According to the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine health literacy assessment, 38% of participants had a reading equivalent of eighth grade or lower. Approximately 30% of participants had limited computer experience. Mean rating for computer skills was 3.31 (SD = 1.18). Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were conducted to examine demographic differences between the two study arms at baseline. Results showed a borderline difference in gender composition between groups, with significantly more females in the VICKY arm (71%) as compared with the MFHP arm (49%; P = 0.051). No other differences were noted. Because of this borderline difference, all subsequent analyses were repeated adjusting for sex to determine its impact on study outcomes.

Tool evaluation

Each family history tool was evaluated for user acceptability ( Table 2 ). The majority of participants rated VICKY as easy to use (91%) and easy to follow (92%) and understood the questions being asked (97%). A majority (83%) also indicated they would recommend VICKY to others, and 77% were highly satisfied. Only 57% indicated they would be likely to use VICKY on their own. VICKY was rated as very good or excellent quality by 62% of participants.

Table 2 also presents the percentage endorsement of evaluation items for the MFHP tool. Notably, for five of eight items, participant evaluation scores for VICKY were significantly higher than for MFHP. Upon adjusting for sex, however, one of the items pertaining to overall satisfaction with the tool was no longer significantly different between VICKY and MFHP (adjusted odds ratio = 2.60; 95% confidence interval: 0.90–7.47; P = 0.0763).

Accuracy of family members identified

As compared with family histories obtained by a genetic counselor, VICKY identified 86% (227/263) of first-degree relatives and 42% (265/632) of second-degree relatives, for a combined accuracy rate of 55% (492/895) for both first- and second-degree relatives. MFHP identified 84% (231/274) of first-degree relatives and 43% (300/699) of second-degree relatives, for a combined accuracy rate of 55% (531/973). No significant differences between the two computerized tools for identifying family members were noted (all P > 0.05). Analyses adjusting for sex were consistent with unadjusted analyses.

Accuracy of health conditions identified

Table 3 presents the sensitivities for six conditions, stratified by tool and type of relative. Overall sensitivity for the six health conditions was 49% for VICKY and 31% for MFHP (P = 0.008). The sensitivity, or true-positive rate, for identifying these conditions was greater for first-degree (60% VICKY, 37% MFHP) than second-degree relatives (33% VICKY, 24% MFHP), regardless of family history tool. As compared with MFHP, VICKY was more accurate in identifying cases of hypertension (P = 0.001) and type 2 diabetes (P = 0.004), the most prevalent conditions within the study sample. Results comparing VICKY with MFHP did not differ when the models were adjusted for sex.

Discussion

Computerized tools that can facilitate the systematic documentation of family health history have been developed in recent years, yet concerns about their usability, particularly among those with limited health literacy, have been raised.14 The present study set out to examine the acceptability and feasibility of using a virtual counselor to electronically document family health history in an underserved patient population. Study participants were willing to enter family history information into the system and found the virtual counselor easy to use, understood the questions being asked, and would recommend VICKY to others. These results demonstrate the acceptability of a virtual counselor, as well as the feasibility of using this platform to collect family health history in an electronic format, while overcoming some of the previously identified barriers for collecting this information among underserved patient populations using existing tools such as MFHP.32,33,34,35

VICKY and MFHP were comparable in terms of identifying the number and relationship of relatives, but they performed differently regarding the identification of health conditions, particularly conditions with a higher prevalence. The questions asked in VICKY and MFHP were relatively similar with regard to the identification of family members, starting with immediate, first-degree relatives and then branching out to allow respondents to include other family members. This similarity in structure likely contributed to the similarities in outcomes observed. Future research should explore different options for soliciting information about second-degree family members because the accuracy of documenting those family members was much lower, regardless of the tool used.36 In the case of the VICKY prototype tested, participants were not asked about nieces or nephews, grandchildren, or half siblings, thus contributing to the lower accuracy levels. These family members will be included in the next version of the VICKY program and we will ascertain the extent to which their inclusion improves the accuracy of second-degree relative documentation.

The differences between MFHP and VICKY in relation to disease conditions suggests that a challenge with the MFHP tool may relate to issues in the entry of disease data. MFHP is capable of collecting information on a larger number of health conditions as compared with VICKY. In addition, MFHP asks about the health conditions using more advanced language and medical terminology (e.g., “hypertension” instead of “high blood pressure”) presented within detailed drop-down menus, which participants had to review to select the corresponding condition. As such, issues in tool content, including the number of diseases collected and the manner in which the disease information is asked for, may contribute to the accuracy of disease collection by any family history tool and warrant attention in future research.

It took study participants an average of 15–30 min to complete their family history on a computer. However, the duration was at times shorter for participants using the MFHP tool because some patients (~11%, 4/35) gave up early after trying unsuccessfully to use the tool. This typically occurred when there were frustrations with navigation and uncertainty about where to go next, as well as the inability to save information that was entered, which was a necessary step to advance in the program. Findings from other studies using MFHP also have reported similar challenges,32,35 suggesting that issues in navigation may also contribute to the disease accuracy outcomes observed for the tool. Notably, all but one of the participants in the VICKY arm were able to complete the program, which may reflect differences in navigation burden between the tools, as the virtual counselor directs navigation to subsequent screens as part of the conversation. We believe this is a key strength of the relational agent system.

This pilot study is the first study to obtain validation data for use of the MFHP Web platform among an underserved patient population. Sensitivity results obtained in this study were significantly lower than results from a previously published validation study of MFHP, which was conducted using a sample of highly educated, white patients participating in genetics research within the ClinSeq cohort.36 Others have examined MFHP within different platforms (telephone) with an underserved patient population and reported lower sensitivity rates.37 Altogether, these studies, along with other qualitative research reporting challenges to using MFHP as a stand-alone system,32,33,34,35 further highlight the need to conduct validation studies of family history tools with a diverse patient population.

There were several limitations to the present study. First, the low prevalence of certain health conditions such as cancer, along with the small sample size of the pilot, greatly limited the comparisons we could make between tools for these conditions. Second, we did not attempt to clarify “heart disease” accuracy, as was done in the prior validation study using MFHP;36 however, this method was used for both tools examined in this study, so no bias was introduced by this approach. As such, heart disease information collected could have included a wide range of heart-related conditions. In addition, because this was a pilot study to demonstrate the acceptability and feasibility of the VICKY program, we were underpowered to test for interactions by health literacy or computer experience. We did, however, find that accuracy outcomes varied by education, health literacy, and computer experience (see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 online). Testing for interactions is a primary aim of the larger trial that is currently under way. Finally, participants in our study were recruited from a volunteer patient registry, which may not be representative of the underserved patient population at our institution and has implications for the generalizability of the findings.

This study also raises questions about methods for using a genetic counselor as the gold standard for comparison. The few family history tool validation studies published to date differ in whether a genetic counselor adapts and supplements pedigree data collected by the automated tool36 or independently collects the health history information.38 The latter approach, which we also used in this pilot study, raises different issues that are challenging to resolve. We observed circumstances in which patients provide family health history to the automated tool that they chose not to reveal to the genetic counselor and/or was missed by the counselor. For example, in our prototype, we also included other conditions to test feasibility, including family history of alcoholism. Notably, there was a high rate of “false positives” (45%), wherein the tool reported family members with alcoholism who were not identified on the gold standard genetic counselor pedigree. In this study we did not recontact participants to get further clarification of their family histories, but it is unlikely that all such reports represent false-positive histories. This is something we will pursue in our next trial in an effort to gain a better understanding of this phenomenon.

As a result of this pilot study, we identified specific opportunities to refine VICKY. These improvements will be applied in the next development phase and include the collection of more complex family trees (e.g., half siblings, twins, nieces/nephews, adopted relatives—which contributed here to lower accuracy rates); additional health conditions; the inclusion of certain navigation features to increase accuracy (e.g., incorporating a “back button” to allow patients to go back a screen and correct errors in data entry); and the expansion of data elements collected in an effort to obtain the minimum core data set for family history information set forth by American Health Information Community.39 Finally, to increase reach and access among underserved minorities, VICKY is also needed in other languages. As such, future plans include programming and testing a Spanish-language version of VICKY.

In sum, efforts to facilitate the electronic documentation of family health history should reflect the diverse needs of the population and ensure that barriers such as health or computer literacy do not limit who is able to access and use such systems effectively. Ultimately, our goal is to improve the systematic documentation and use of family history in primary care to identify those at greatest risk for chronic diseases, who would benefit from preventive intervention efforts.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Guttmacher AE, Collins FS, Carmona RH . The family history–more important than ever. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2333–2336.

Pyeritz RE . The family history: the first genetic test, and still useful after all those years? Genet Med 2012;14:3–9.

Valdez R, Yoon PW, Qureshi N, Green RF, Khoury MJ . Family history in public health practice: a genomic tool for disease prevention and health promotion. Annu Rev Public Health 2010;31:69–87 1 p following 87.

O’Neill SM, Rubinstein WS, Wang C, et al.; Family Healthware Impact Trial group. Familial risk for common diseases in primary care: the Family Healthware Impact Trial. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:506–514.

Yoon PW, Scheuner MT, Peterson-Oehlke KL, Gwinn M, Faucett A, Khoury MJ . Can family history be used as a tool for public health and preventive medicine? Genet Med 2002;4:304–310.

Doerr M, Eng C . Personalised care and the genome. BMJ 2012;344:e3174.

Heald B, Edelman E, Eng C . Prospective comparison of family medical history with personal genome screening for risk assessment of common cancers. Eur J Hum Genet 2012;20:547–551.

Wilson BJ, Qureshi N, Santaguida P, et al. Systematic review: family history in risk assessment for common diseases. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:878–885.

Giovanni MA, Murray MF . The application of computer-based tools in obtaining the genetic family history. Curr Protoc Hum Genet 2010;Chapter 9:Unit 9.21.

Rich EC, Burke W, Heaton CJ, et al. Reconsidering the family history in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:273–280.

Berg AO, Baird MA, Botkin JR, et al. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: Family History and Improving Health. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:872–877.

Kanetzke EE, Lynch J, Prows CA, Siegel RM, Myers MF . Perceived utility of parent-generated family health history as a health promotion tool in pediatric practice. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2011;50:720–728.

Wood ME, Stockdale A, Flynn BS . Interviews with primary care physicians regarding taking and interpreting the cancer family history. Fam Pract 2008;25:334–340.

Wang C, Gallo RE, Fleisher L, Miller SM . Literacy assessment of family health history tools for public health prevention. Public Health Genomics 2011;14:222–237.

Institute of Medicine. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2004.

Kirsch I, Jungeblut A, Jenkins L, Kolstad A . Adult Literacy in America: A First Look at the Results of the National Adult Literacy Survey. National Center for Educational Statistics, US Department of Education: Washington, DC, 1993.

Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR . The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:175–184.

Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C . The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006–483). National Center for Educational Statistics, US Department of Education: Washington, DC, 2006.

Bickmore TW, Pfeifer LM, Byron D, et al. Usability of conversational agents by patients with inadequate health literacy: evidence from two clinical trials. J Health Commun 2010;15(suppl 2):197–210.

Bickmore T, Puskar K, Schlenk E, Pfeifer L, Sereika S . Maintaining reality: relational agents for antipsychotic medication adherence. Interact Comput 2010;22:276–288.

Bickmore TW, Pfeifer LM, Paasche-Orlow MK . Health document explanation by virtual agents. Intelligent Virtual Agents, Proc 2007;4722:183–196.

Bickmore TW, Pfeifer LM, Paasche-Orlow MK . Using computer agents to explain medical documents to patients with low health literacy. Patient Educ Couns 2009;75:315–320.

Edwards RA, Bickmore T, Jenkins L, Foley M, Manjourides J . Use of an interactive computer agent to support breastfeeding. Matern Child Health J 2013;17:1961–1968.

Bickmore T, Cange A, Kulshreshtha A, Kvedar J . An Internet-based virtual coach to promote physical activity adherence in overweight adults: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e1.

Bickmore TW, Mauer D, Brown T . Context awareness in a handheld exercise agent. Pervasive Mob Comput 2009;5:226–235.

Bickmore TW, Silliman RA, Nelson K, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an automated exercise coach for older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:1676–1683.

Ellis T, Latham NK, DeAngelis TR, Thomas CA, Saint-Hilaire M, Bickmore TW . Feasibility of a virtual exercise coach to promote walking in community-dwelling persons with Parkinson disease. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2013;92:472–481; quiz 482.

King AC, Bickmore TW, Campero MI, Pruitt LA, Yin JL . Employing virtual advisors in preventive care for underserved communities: results from the COMPASS study. J Health Commun 2013;18:1449–1464.

Sequeira SS, Eggermont LH, Silliman RA, et al. Limited health literacy and decline in executive function in older adults. J Health Commun 2013;18(suppl 1):143–157.

Arozullah AM, Yarnold PR, Bennett CL, et al. Development and validation of a short-form, rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine. Med Care 2007;45:1026–1033.

Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med 1993;25:391–395.

Berger KA, Lynch J, Prows CA, Siegel RM, Myers MF . Mothers’ perceptions of family health history and an online, parent-generated family health history tool. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2013;52:74–81.

Wallace JP, Baugh C, Cornett S, et al. A family history demonstration project among women in an urban Appalachian community. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2009;3:155–163.

Arar N, Delgado E, Lee S, Abboud HE . Improving learning about familial risks using a multicomponent approach: the GRACE program. Per Med 2013;10:35–44.

Arar N, Seo J, Abboud HE, Parchman M, Noel P . Veterans’ experience in using the online Surgeon General’s family health history tool. Per Med 2011;8:523–532.

Facio FM, Feero WG, Linn A, Oden N, Manickam K, Biesecker LG . Validation of My Family Health Portrait for six common heritable conditions. Genet Med 2010;12:370–375.

Murray MF, Giovanni MA, Klinger E, et al. Comparing electronic health record portals to obtain patient-entered family health history in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:1558–1564.

Cohn WF, Ropka ME, Pelletier SL, et al. Health Heritage© a web-based tool for the collection and assessment of family health history: initial user experience and analytic validity. Public Health Genomics 2010;13:477–491.

Feero WG, Bigley MB, Brinner KM ; Family Health History Multi-Stakeholder Workgroup of the American Health Information Community. New standards and enhanced utility for family health history information in the electronic health record: an update from the American Health Information Community’s Family Health History Multi-Stakeholder Workgroup. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2008;15:723–728.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by grants from the Boston University School of Public Health and the Boston University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (NCRR UL1RR025771). In addition, C.W. was supported by the National Cancer Institute (K07 CA131103) and a Peter T. Paul career development professorship from Boston University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables

(DOC 44 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Bickmore, T., Bowen, D. et al. Acceptability and feasibility of a virtual counselor (VICKY) to collect family health histories. Genet Med 17, 822–830 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2014.198

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2014.198

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Finding the sweet spot: a qualitative study exploring patients’ acceptability of chatbots in genetic service delivery

Human Genetics (2023)

-

Cognitive plausibility in voice-based AI health counselors

npj Digital Medicine (2020)

-

Applying theory to characterize impediments to dissemination of community-facing family health history tools: a review of the literature

Journal of Community Genetics (2020)

-

Validation of a digital identification tool for individuals at risk for hereditary cancer syndromes

Hereditary Cancer in Clinical Practice (2019)