Abstract

Purpose:

Previous studies have suggested that genomic investigators generally favor offering to return at least some secondary findings to participants and believe that participants’ preferences should determine the information they receive. We surveyed investigators to ascertain their views on four models of informed consent for this purpose: traditional consent, staged consent, mandatory return, and outsourced consent.

Methods:

We performed an online survey of the views regarding return of secondary results held by 198 US genetic researchers drawn from our subject pool for an earlier study. Potential participants were identified through the National Institutes of Health RePORTER database and abstracts from the 2011 American Society of Human Genetics meeting.

Results:

Under circumstances in which resource constraints are not an issue, approximately a third of respondents would endorse either staged consent or traditional consent; outsourced consent and mandatory return are favored by only a small minority. However, taking resource constraints into account, roughly half the sample would favor traditional consent, with support for staged consent dropping to 13%.

Conclusion:

Despite their liabilities, traditional approaches to consent are seen as the most viable under current circumstances. However, there is considerable interest in staged consent, assuming the infrastructure to support it can be provided.

Genet Med 17 8, 644–650.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The potential for research using whole-exome/whole-genome sequencing to generate secondary results (i.e., findings that do not relate to the primary aim of the study) has attracted considerable attention. Secondary findings may identify risks of varying degrees for the development of medical conditions, some preventable and others not; carrier states that may have implications for reproductive decision making by participants and their family members; propensities for drug metabolism that may affect drug efficacy and risk of side effects; and other information of personal interest to participants.1 Hence, whether to return secondary results—and, if so, which results to return—has become a major concern for genomic researchers.2,3

Surveys and focus groups involving research participants and potential participants suggest strong support for offering a wide range of secondary findings to research participants, with a particular desire for information on conditions for which preventive interventions are available.4,5,6 Although some investigators have expressed concerns about the burden associated with such an obligation,7 surveys of genomic researchers have demonstrated surprisingly strong support for return of a variety of secondary results.1,8,9,10 Expert panels have endorsed this approach, although without unanimity regarding the precise scope of potential disclosure.2,11,12,13 Normative analyses have identified a variety of grounds on which a duty to return secondary findings may be based.14,15 At the same time, there seems to be considerable support for the conclusion that investigators do not have an obligation to “hunt” for secondary results that would not otherwise be apparent in their data analysis.2,16

Because the preferences of research participants regarding return of secondary findings may vary, most commentators seem to agree that once investigators determine which secondary findings will be offered, the ultimate decision about whether to accept the offer should rest with the participants themselves.2,11,12,17 This implies that some sort of informed consent process for these decisions is needed. In our previous survey of investigators’ views on the content of consent disclosures regarding secondary findings, we reported endorsement of a broad set of items to disclose, including categories of findings being offered, a wide range of potential benefits and risks of receiving secondary findings, implications for family members, how results would be dealt with if the participant were to become incompetent or die, data security measures, and how secondary findings from subsequent studies using participants’ samples or data would be addressed.18 We also found that despite the complex decisions to be made and the extensive disclosures that investigators thought were needed, most researchers were willing to devote no more than 15–30 min to this aspect of the consent process.18

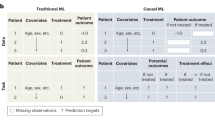

Given the apparent discrepancy between the amount of information to be discussed with participants and the limited time available to do it, we explored the range of possible models of consent that might be used. Based on our review of the literature, survey of genomic investigators, and interviews with investigators and research participants, we identified four models of informed consent for the return of secondary findings ( Table 1 ): (i) traditional consent, in which consent to the return of specific categories of secondary findings is obtained at the time of—but not as a condition of—enrollment in the genomic research study; (ii) staged consent, with brief mention of secondary findings at the time of initial consent but with more detailed consent for return of specific findings obtained if and when reportable results are found; (iii) mandatory return, in which consent to the return of specific categories of secondary findings is obtained at the time of—and as a condition of—enrollment; and (iv) outsourced consent, in which participants are given the raw results of their sequencing and referred to third parties for consent, analysis, and return of desired categories of secondary findings.19 We recognized that hybrid models could be identified and that other options might become available in the future but consider these four options as exemplifying the current range of potential approaches to consent.

Although we were able to identify a number of advantages and disadvantages of each of these approaches, we wanted to know how genomic investigators themselves viewed these options. Not only will researchers have a good deal of control over the approaches to consent that are used in their studies, they are also likely to identify advantages and disadvantages of different options that may not be apparent to outsiders. To tap those insights, we returned to our original sample of genomic investigators to gather their views on these models of informed consent.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The participant pool for this survey was essentially the same as in our initial survey of investigators’ views on the return of incidental findings.1 We identified genetic researchers by (i) searching the National Institutes of Health RePORTER database in 2012 for principal and coprincipal investigators of currently funded grants using a combination of key words (e.g., human genetic, human genomics, genetic epidemiology, exome sequencing, whole-genome sequencing, genome-wide association) and (ii) applying similar criteria to abstracts from the 2011 American Society of Human Genetics meeting. Only investigators whose research focus was human disease gene identification were included. E-mail addresses were identified using online resources. Researchers outside the United States and those for whom no e-mail address was found were excluded. For this study we invited all researchers identified through this process to participate (n = 769), whether or not they had participated in the earlier study. Of the 769 researchers invited to participate, 56 e-mail addresses were incorrect, and 3 researchers indicated that they were not conducting relevant research. Of the remaining 710 researchers, 198 responded to the survey, for a response rate of 27.9%.

Instrument

Survey questions aimed at characterizing respondents, including their training and involvement in genetic research, were identical to those in the initial survey. In addition, a set of questions was developed to ascertain respondents’ views regarding the four models of consent identified in the first part of this study. The survey included the brief, one-paragraph descriptions of each option in Table 1 (unbulleted) so that respondents would have common definitions on which to base their responses. Because the initial American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics recommendations for mandatory return of certain secondary findings20 had not yet been modified, the word initial did not appear in the description of model 3. The following definition of incidental/secondary findings was provided: “results other than those related to the specific aims of the study, whether or not they were deliberately sought.” A draft of the survey was reviewed by members of the interdisciplinary research team and revised for clarity and conciseness.

Procedures

Researchers who were eligible for the survey were contacted by e-mail to solicit participation. They were invited to click on a link to surveymonkey.com, where the first page included an informed consent disclosure and a statement that proceeding with the survey indicated consent to participate. E-mail reminders were sent to nonrespondents ~1 and 2 weeks after the initial invitation. Investigators were offered a $25 gift certificate for completion of the survey, which was conducted over a 5-week period in the fall of 2013. Procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of Columbia University Medical Center and the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Data analysis

Responses from the survey are provided in aggregate form with descriptive statistics; percentages are calculated on the basis of the total number of participants in the study, and the number of respondents for each item is indicated in the tables. Contingency tables were used to examine the relationship between categorical variables and the choice of models of consent, and P values from χ2 tests or Fisher exact tests were calculated. For continuous variables, simple multinomial regression models were fit, with the continuous variable as the predictor. All significant demographic, experiential, and attitudinal variables from these analyses were entered as predictors into a multinomial logistic regression in which the outcome was the choice of consent model; the traditional consent model was used as the reference outcome level. To compare the ratings of consent models on a set of dimensions, linear mixed models were fit, including dimensional ratings as the outcome, consent models as the predictors, and random intercepts for respondents to account for correlation of responses from the same respondent. Pairwise comparisons of the four consent models were then conducted, with unplanned contrasts created to further compare group differences. Although each question was framed in terms of both “incidental” and “secondary” findings, given that both terms have been used to refer to the same genomic data,21 for reasons of simplicity we refer exclusively to secondary findings in the results that follow. Quotations from free-text responses to survey questions, which are used to illustrate the basis for researchers’ responses, are identified by subject number.

Results

Respondent characteristics

Respondents to the survey are characterized in Tables 2 and 3 . In summary, the researchers who responded to the survey (n = 198) were diverse in terms of training, including PhDs (59.1%), MDs (18.7%), MD/PhDs (12.1%), and others (10.1%). They were predominately male (62.6%) and Caucasian (75.3%), with a mean age of 44 years. As a group, respondents were experienced in conducting genomic research. Almost half (49.0%) had at least 6 years’ experience enrolling participants or collecting samples in human genetic research, and a substantial minority (28.8%) had at least 11 years’ experience. The vast majority had used whole-exome (77.3%) or whole-genome (55.6%) sequencing in their research, and approximately 39% had obtained consent from research subjects.

Experience and attitudes regarding return of results to research participants

One-sixth of the researchers (16.7%; n = 33) had returned secondary findings, although many more noted that at least some of their consent forms from past or current studies would allow such return (30.3%; n = 60). More than one-quarter of the researchers who responded to the survey indicated that they planned to disclose secondary genetic findings to participants in future research studies (28.8%; n = 57); a smaller group (20.2%; n = 40) planned to disclose such findings to previously enrolled participants. Almost a third of respondents (31.8%; n = 63) had returned genetic research results that were the focus of the study to subjects, although a larger proportion (40.4%; n = 80) reported that at least some of their consent forms allowed such findings to be returned.

When asked whether prospective participants should be given the option of deciding whether they want incidental or secondary findings returned, an overwhelming proportion (82.3%; n = 163) responded “yes” or “probably yes.” At the same time, however, most respondents believed that being required to return at least some secondary findings would represent a substantial burden for researchers, with 66.6% (n = 132) characterizing the burden as at least “moderate” and 38.9% (n = 77) calling it “significant” or “very heavy.” When asked about the importance of a variety of resources that would assist them in returning secondary findings to participants, half or more of respondents identified the following as “essential”: qualified staff and/or genetic counselors to educate participants (72.2%); well-curated mutation and polymorphism databases (59.6%); and guidance for institutional review boards on returning secondary findings (52.0%) ( Table 4 ). In addition, 46.5% said accessible software to efficiently analyze sequence data was essential. Indeed, a majority of respondents indicated that all of the resources in Table 4 were at least “important” to the possibility of returning secondary findings.

Preferences for models of consent for return of secondary findings

Respondents were asked to rate each of the models on eight dimensions (see Table 5 ) that might be relevant to choosing the most desirable approach, as well as to provide an indication of their overall preferences. Ratings were made on a five-point Likert scale. As shown in Table 5 , traditional consent was rated highest on all but one dimension, with staged consent second (although the differences between their scores were mostly not significant); mandatory return and outsourced consent were rated lowest on most dimensions. Of note, outsourced consent was deemed best at limiting the burden on researchers. Although considerations of burden might be considered a potent concern for investigators, when asked to rate how well each model reflected their views of the best approach to informed consent, the group expressed a strong preference for traditional consent, followed by staged consent, with mandatory return and outsourced consent clearly least favored.

Participants in the survey were also asked directly which model they would prefer to implement in an ideal scenario in which constraints such as time and cost of implementing the model were not at issue. Traditional consent (32.3%; n = 64) and staged consent (32.3%; n = 64) were the clear favorites, with outsourced consent (13.1%; n = 26) and mandatory return (8.6%; n = 17) attracting less support. However, the favored choices shifted when respondents were asked which model they would prefer to implement taking into account the realities of their research setting (including time, cost, and staffing). Under these more realistic circumstances, traditional consent was the clear favorite (47.8%; 94), followed by outsourced consent (18.7%; n = 37), staged consent (13.1%; n = 26), and mandatory return (6.6%; n = 13).

A multiple regression analysis looked at the predictors of the most favored model under this more realistic set of conditions. All demographic, experiential, and attitudinal variables that had been significantly associated with choice of consent model in simple analyses were entered into the regression. These include age, having experience returning secondary findings, and extent of perceived burden of returning secondary results. The resulting model significantly predicted choice of approach to informed consent (likelihood ratio test, χ2 = 24.58; degrees of freedom = 9; P = 0.004). Compared with traditional consent, increased age was associated with a reduced preference for outsourced consent (odds ratio (OR) = 0.94; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.90–0.98; P = 0.005); having returned incidental findings was associated with a reduced preference for staged consent (OR = 0.10; 95% CI = 0.01–0.80; P = 0.03); and feeling that return of secondary findings was more burdensome was associated with an increased preference for outsourced consent (OR = 1.54; 95% CI = 1.01–2.33; P = 0.04).

Explaining preferences for models of consent

After selecting their preferred model of consent, respondents were given an opportunity to enter comments in a text box. Although only a minority of participants chose to do so (n = 34), and hence their comments cannot be considered representative, they do illuminate aspects of respondents’ thinking in choosing or rejecting particular models of consent.

Traditional consent

Pro: “I think it makes it easier for all participants to know the extent of their involvement, responsibility and benefits from the very beginning. …” (S14)

Con: “The traditional consent has the problem of needing changes over time, and the mandate of what to return always changes.” (S35)

Staged consent

Pro: “I strongly believe that [staged consent] would be the best ethical model; however, funds would have to accompany grants to allow for this infrastructure to be set up (longitudinal followup, genetic counselor in the study, re-consenting). Having this longitudinal followup, though, could be very beneficial for updating phenotypic information as well.” (S18)

Con: “This would require additional staff.” (S17)

Mandatory return

Pro: “In an ideal scenario, incidental findings that are clinically actionable and related to high penetrance genes should be reported to participants.” (S24)

Con: “[I] believe mandatory return is unethical.” (S4)

Outsourced consent

Pro: “I am not a geneticist and am not expert in all of the other genetic diseases and do not wish to be so. Give the company or laboratory or institution they choose access to the data if patients or parents wish and let the “experts take care of it.”” (S30)

Con: “While [outsourcing] would be the easiest to implement, I am not comfortable with passing the full burden of obtaining interpretation of incidental findings onto the participants especially in light of the potential cost in finding a competent genetic counselor/medical geneticist to interpret [whole-exome sequencing/whole-genome sequencing] data at this stage. Further, passing off the burden could discourage participants from underrepresented minorities, making the extra cost of [traditional consent] worth it in my opinion.” (S9)

Other

“I am against return of results in all circumstances.” (S32)

Discussion

This group of experienced genomic researchers, while strongly supporting the idea that prospective participants should be given the option of deciding whether they want secondary findings returned, reflected no clear consensus regarding a preferred model of informed consent for that purpose. Under optimal circumstances, in which resource constraints were not an issue, nearly a third would endorse traditional consent and a like number would favor staged consent; outsourced consent and mandatory return were favored by only a small minority. However, if resource constraints were taken into account, almost half the sample would favor traditional consent, with support for staged consent dropping to 13% and outsourced consent embraced by 19%. Despite their liabilities, traditional approaches to consent are considered to be the most viable under current circumstances. Enthusiasm for staged consent is clearly held in check by concerns about the resources that would be necessary to implement it.

These preferences reflect respondents’ characterizations of each model, with traditional consent and staged consent ranking first and second on most dimensions. These included their efficacy in educating participants, reducing their anxiety, and encouraging them to enroll in genomic research, as well as their distribution of burdens and benefits and overall ethical preferability. That the outsourced consent model, which was rated most highly on reducing the burden on researchers, was endorsed by only about a fifth of our sample indicates that these considerations do not play a dominant role in most investigators’ preferences for approaches to consent. This is particularly notable given respondents’ views about the considerable burden represented by an obligation to return secondary results and the substantial resources they think are essential to do it. As the perceived burden of returning results increased, however, our respondents were significantly more likely to endorse an outsourced consent model, which would remove the burden from them entirely.

Lack of support for mandatory return of secondary findings—no more than 10% of respondents endorsed it under any scenario, and it scored poorly on all dimensions—is worth additional comment. On its face, mandatory return should be attractive to researchers, for whom it would clearly define their obligations to research participants. In addition, by eliminating participant choice and hence reducing the amount of information that would need to be disclosed to potential participants, it should simplify and shorten the consent process. Mandatory return of selected secondary findings was initially endorsed for clinical exome/genome sequencing by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics19 (although its recommendations were later changed to allow patients to opt out22); thus the approach is undoubtedly familiar to many of our respondents who are knowledgeable about clinical testing. Moreover, it has been adopted by at least some genomic research groups.23 The researchers in our sample, however, seemed to be concerned about both the ethics of returning findings that a person may not want and the possible negative impact on recruitment of forcing unwanted information on research participants.

Researchers’ characteristics and experience seemed not to have a major impact on their attitudes and preferences. The multivariate analysis suggesting that respondents who feel greater burden are more likely to endorse outsourced consent is intuitively appealing because that option was perceived as placing the fewest obligations on investigators. However, the other results regarding age and previous experience returning results—each of which is associated with a reduced preference for one other model as compared with traditional consent—are not susceptible to easy interpretation.

The limitations of our data should be noted. Although ascertained systematically, our sample is not necessarily representative of all genomic researchers. Moreover, only a minority of our respondents (17%) had actually returned secondary findings or had consent forms that explicitly offered this possibility (30%). Hence, their experience with obtaining consent for return of secondary findings is limited, and it is possible that their views will change as they become more familiar with the process. When we asked respondents about their views regarding which consent model they would prefer to implement taking into account the realities of their research setting, it is likely that respondents had different settings in mind, and we do not know whether their responses would have been more consistent or different had the setting been standardized. Finally, as this study is descriptive rather than one testing a hypothesis, the statistical findings should be interpreted cautiously.

What are the implications of our findings for the future of informed consent to genomic sequencing? As we discuss elsewhere, no model of consent satisfies all the desiderata for informing participants of their options in a meaningful way.19 Among the considerations that should enter into choosing a model are the extent to which it is consistent with researchers’ ethical obligations and to which it comports with the practical realities of the research setting.19 In that context, investigators’ preference for a traditional model of consent could represent the allure of the familiar, despite its limitations. In addition, there is clearly a sense—as a comment quoted above illustrates—that wrapping up the entire consent process at the outset, so both researchers and participants know exactly what data will be returned, is the fairest way of approaching the issue. This is underscored by respondent ratings of the models of consent on dimensions including fairness, ethical desirability, and efficacy in informing and reassuring participants. However, some of the narrative comments indicate that investigators are not oblivious to the disadvantages of obtaining consent for return of results at the time of enrollment, including the burden of having these discussions with every prospective participant and the impact of changes in scientific knowledge and participant preferences over time.

Hence, many investigators were attracted to the staged consent model, which promises greater overall efficiency of the consent process, in that only participants for whom there are returnable findings need engage in decision making, and allows decisions to be made in light of the most up-to-date knowledge and participant preferences. Their endorsement of this approach, however, was clearly dependent on the availability of resources to support iterative contact with participants and provision of the necessary information for them to make informed choices. In addition, whether respondents who rated this option highly took into account another major issue associated with the staged approach—recontacting participants to alert them that a secondary finding is available in itself provides information that some participants may not want to have—is not clear. Nonetheless, as more high-volume research centers develop such infrastructure, this may become an increasingly popular option.

Research on current approaches to consent for genomic sequencing in research, including return of secondary results, has been almost entirely normative and descriptive.22,24 Evidence-based decisions about the optimal approach to consent, however, will require studies that compare the effectiveness of various approaches, for example, traditional versus staged consent. Data on how well the models perform in educating participants, facilitating decision making, reducing anxiety, increasing satisfaction, and promoting enrollment—and about the relative costs of the different models—will become increasingly important as genomic research is conducted in a growing number of centers. Indeed, findings on these issues may enable the development of hybrid models that combine the advantages of more than one approach. This would seem to be the next logical step for research on consent to genome sequencing in both research and clinical settings.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Klitzman R, Appelbaum PS, Fyer A, et al. Researchers’ views on return of incidental genomic research results: qualitative and quantitative findings. Genet Med 2013;15:888–895.

Jarvik GP, Amendola LM, Berg JS, et al.; eMERGE Act-ROR Committee and CERC Committee; CSER Act-ROR Working Group. Return of genomic results to research participants: the floor, the ceiling, and the choices in between. Am J Hum Genet 2014;94:818–826.

McEwen JE, Boyer JT, Sun KY . Evolving approaches to the ethical management of genomic data. Trends Genet 2013;29:375–382.

Murphy J, Scott J, Kaufman D, Geller G, LeRoy L, Hudson K . Public expectations for return of results from large-cohort genetic research. Am J Bioeth 2008;8:36–43.

Kaufman D, Murphy J, Scott J, Hudson K . Subjects matter: a survey of public opinions about a large genetic cohort study. Genet Med 2008;10:831–839.

Bollinger JM, Bridges JFP, Mohamed A, Kaufman D . Public preferences for the return of research results in genetic research: a conjoint analysis. Genet Med 2014; e-pub ahead of print 22 May 2014.

Cassa CA, Savage SK, Taylor PL, Green RC, McGuire AL, Mandl KD . Disclosing pathogenic genetic variants to research participants: quantifying an emerging ethical responsibility. Genome Res 2012;22:421–428.

Yu JH, Harrell TM, Jamal SM, Tabor HK, Bamshad MJ . Attitudes of genetics professionals toward the return of incidental results from exome and whole-genome sequencing. Am J Hum Genet 2014;95:77–84.

Fernandez CV, Strahlendorf C, Avard D, et al. Attitudes of Canadian researchers toward the return to participants of incidental and targeted genomic findings obtained in a pediatric research setting. Genet Med 2013;15:558–564.

Ramoni RB, McGuire AL, Robinson JO, Morley DS, Plon SE, Joffe S . Experiences and attitudes of genome investigators regarding return of individual genetic test results. Genet Med 2013;15:882–887.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group; Fabsitz RR, McGuire A, Sharp RR, et al. Ethical and practical guidelines for reporting genetic research results to study participants: updated guidelines from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2010;3:574–580.

Wolf SM, Lawrenz FP, Nelson CA, et al. Managing incidental findings in human subjects research: analysis and recommendations. J Law Med Ethics 2008;36:219–48, 211.

Wolf SM, Crock BN, Van Ness B, et al. Managing incidental findings and research results in genomic research involving biobanks and archived data sets. Genet Med 2012;14:361–384.

Bredenoord AL, Kroes HY, Cuppen E, Parker M, van Delden JJ . Disclosure of individual genetic data to research participants: the debate reconsidered. Trends Genet 2011;27:41–47.

Richardson HS . Moral Entanglements: The Ancillary-Care Obligations of Medical Researchers. Oxford University Press: New York, 2012.

Gliwa C, Berkman BE . Do researchers have an obligation to actively look for genetic incidental findings? Am J Bioeth 2013;13:32–42.

Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues. Anticipate and Communicate: Ethical Management of Incidental and Secondary Findings in the Clinical, Research, and Direct-to-Consumer Contexts. Washington, DC, 2013.

Appelbaum PS, Waldman CR, Fyer A, et al. Informed consent for return of incidental findings in genomic research. Genet Med 2014;16:367–373.

Appelbaum PS, Parens E, Waldman CR, et al. Models of consent to return of incidental findings in genomic research. Hastings Cent Rep 2014;44:22–32.

Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, et al.; American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med 2013;15:565–574.

Parens E, Appelbaum P, Chung W . Incidental findings in the era of whole genome sequencing? Hastings Cent Rep 2013;43:16–19.

American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Incidental findings in clinical genomics: a clarification. Genet Med 2013;15:664–666.

Henderson GE, Wolf SM, Kuczynski KJ, et al. The challenge of informed consent and return of results in translational genomics: empirical analysis and recommendations. J Law Med Ethics 2014;42:344–355.

Ayuso C, Millán JM, Mancheño M, Dal-Ré R . Informed consent for whole-genome sequencing studies in the clinical setting. Proposed recommendations on essential content and process. Eur J Hum Genet 2013;21:1054–1059.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank those who participated in this study. This work was funded by grants from the National Human Genome Research Institute: R21 HG006596 (P.S.A., principal investigator), R01 HG006600 (W.K.C., principal investigator), and P50 HG007257 (P.S.A., principal investigator).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Appelbaum, P., Fyer, A., Klitzman, R. et al. Researchers’ views on informed consent for return of secondary results in genomic research. Genet Med 17, 644–650 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2014.163

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2014.163

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Engaging Hmong adults in genomic and pharmacogenomic research: Toward reducing health disparities in genomic knowledge using a community-based participatory research approach

Journal of Community Genetics (2017)

-

Effect of Public Deliberation on Attitudes toward Return of Secondary Results in Genomic Sequencing

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2017)

-

Anticipating the Ethical Challenges of Psychiatric Genetic Testing

Current Psychiatry Reports (2017)