Abstract

Purpose: To explore health-related quality of life as measured with Short Form 36 in adults with verified Marfan syndrome and to compare with the general population, other groups with chronic problems and studies on Marfan syndrome. Furthermore, to study potential correlations between the scores on the subscales of Short Form 36 and the presence of biomedical criteria and symptoms of Marfan syndrome.

Method: Cross-sectional study. Short Form 36 was investigated in 84 adults with verified Marfan syndrome.

Results: The study group had reduced scores on all eight subscales of Short Form 36 compared with the general population, comparable with other groups with chronic diseases. Compared with earlier Short Form 36 results in Marfan syndrome, we found lower scores for social function, vitality, general health, bodily pain, and role physical. No correlations of substantial explanatory values were found between the Short Form 36 subscales and gender, body mass index, ascending aortic surgery, use of β-blockers, visual acuity, joint hypermobility, fulfillment of the five major Ghent criteria, and number of major criteria fulfilled. Potential explanations are discussed.

Conclusion: Persons with Marfan syndrome have reduced scores for health-related quality of life as measured with Short Form 36, comparable with those in other chronic disorders and disabilities. The reduction does not seem to be related to biomedical criteria or symptoms of Marfan syndrome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Marfan syndrome (MFS) is an autosomal dominant connective tissue disorder, with variable pathologic features and symptoms from different organ systems. MFS is diagnosed on the basis of the Ghent criteria,1 defining “involved organ systems” and “major criteria fulfilled.” To be given the diagnosis, a person has to fulfill a major criterion in two different organ systems and have a third organ system involved. Approximately 30% of the cases are the first in their family to have MFS, interpreted as caused by new mutations.

The impact of MFS on the individual patient may vary considerably both between families and within a family. As aortic disease may result in early death, some patients will have to cope with an impending life-threatening condition. Lens dislocation can give reduced visual acuity, and lens dislocation increases the risk for retinal detachment that can result in blindness. The consequences of dural ectasia are still unclear2; orthostatic headache due to cerebrospinal hypotension has been found3,4; problems with spinal and epidural anesthesia have been reported.5 Skeletal abnormalities may include a long, slender body shape, chest deformities, scoliosis, and joint hypermobility and may result in a peculiar appearance that invites unwanted attention. Children with MFS often look older than their chronological age and are often treated in accordance with their appearance, rather than their actual age. Individuals with MFS have been bullied and stigmatized at school, in the local environment, and in their occupational life.6 Moreover, persons with MFS often report musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, and reduced physical endurance.7,8

In the clinic, persons with MFS usually report few, if any, physical limitations deriving from their cardiovascular system. On the other hand, physicians often advise abstinence from strenuous exercise and prescribe beta-blockers to reduce the aortic dP/dt, heart rate, blood pressure, and left ventricular afterload, with the intention to delay aortic dilatation and lower the risk of aortic dissection. Some patients undergo prophylactic elective graft operations for enlarged aortas. Through such measures, the median life expectancy of persons with MFS has been prolonged considerably.9 To reduce the risk of aortic dissection, lens dislocation, and retinal detachment, the patients are advised not to participate in contact sports and to wear glasses during sports with small balls. It is our clinical experience that the advised restrictions have often resulted in passivity; a sedentary life with an increasing body size.

Given the broad range of symptoms and characteristics among individuals with MFS, as mentioned earlier, one would expect a reduced health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Judging from the MFS literature, where the main focus is on aortic pathology, the severity of aortic disease could potentially be the most important predictor for the degree of reduction. There are, however, few studies of HRQOL in the literature on MFS. In a study of 174 adults with MFS, Peters et al.10 concluded that the overall quality of life was adequate but found a significant decrease within the psychological domain, particularly regarding reproductive decision making. In three studies, the Short Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire2,11,12 was applied, but the patient groups were small (36 persons with MFS,11 22 persons with MFS and dural ectasia2, and 15 persons with MFS primarily assessed for sleep apnoea12). In all three studies, lower levels of SF-36 scores than in healthy controls were found. However, the interpretations were divergent. In these studies, the potential associations between fulfillment of the different major criteria and subscales of SF-36 were not explored. In our ongoing MFS studies, we have, therefore, included one of the most commonly used generic questionnaires, SF-36, which is often applied as a measure of HRQOL.

SF-36 has been used as measure of HRQOL in a Norwegian study of the general population.13 In this study, women had significantly lower scale scores than men in all SF-36 subscales.

HYPOTHESES

We expected (1) that the SF-36 scores would be lower, indicating lower HRQOL, in the domains of mental health (MH), social functioning (SF), emotional role functioning, vitality (VT), general health (GH), bodily pain (BP), physical functioning, and role physical functioning in our MFS sample compared with healthy controls and that (2) the proposed lower levels of SF-36 scores would be associated with higher age, female gender, higher body mass index (BMI), ascending aortic surgery, β-blockers, reduced visual acuity, joint hypermobility, fulfillment of the five major Ghent criteria, and the number of major criteria fulfilled.

To test these hypotheses, this study was undertaken to investigate HRQOL of adults with verified MFS and to compare the results (1) with findings in a gender- and age-matched control group from the Norwegian general population, (2) with results from patients with other chronic disorders with similar problems, and (3) with results of contemporary HRQOL studies on MFS. A further aim was to explore the associations between each of the eight subscales of SF-36 and demographic variables, MFS symptoms, and MFS criteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In the Norwegian Marfan study, 105 adult Norwegians with presumed MFS were prospectively investigated for all features in the Ghent criteria1 by the same group of investigators. Eighty-seven of these 105 persons fulfilled the Ghent criteria, 73 of them carrying a FBN1 mutation; 42 unique mutations were found among 44 probands, 9 of them previously reported in the Universal Mutation Database, the FBN1 Mutation Database, and 33 considered novel. Details about the investigations and results have been presented previously.14–17 Eighty-four of the 87 persons answered the SF-36 questionnaires completely, of whom 63% were women, median age 42 years (range, 20–69) and 37% were men, median age 35 years (range, 19–69). Three female subjects (age, 32–54 years) did not complete the questionnaires and were excluded from further analysis.

A control group (general population [GP]) was drawn from an SF-36 dataset from the general population (Norwegian Social Science Data Service; “Level of living 2002”) for comparison. For each person in the study group, five persons from the general population were drawn, matched for age and gender.

In addition, results from studies of patient cohorts with the following significant chronic diseases in the same age group were selected for comparison: Uveitis,18 to compare the MFS group with a group with a risk of permanently reduced visual acuity; hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)19 without angina, to compare the impact of anxiety concerning early cardiovascular death; and cystic fibrosis (CF)20 and Behçet syndrome (BS)21 (an autoimunologic disorder affecting uvea, joints, spine, and sacrum and giving oral and genital ulcera), to compare with two other well-defined multiorgan diseases with chronic disability and reduced life span.

The SF-36 Version 1, taken from the Medical Outcome Study,22 is a widely used questionnaire, which is considered to be a valid and reliable measure of HRQOL. It consists of 36 questions; each question is used as part of one of eight subscales.23 There are four subscales in the psychological/mental domain: MH, role functioning emotional, SF, and VT; and four subscales in the physical domain: GH, BP, physical functioning, and role functioning physical (“role functioning physical” measures reductions in daily activities and work caused by physical health problems). The scores for all subscales in SF-36 range from 0 to100, with100 as the best score.23 Mean scores may be reported for each individual subscale and for two sum scores, the mental component summary (MCS) and physical component summary (PCS).

BMI = body mass (kg)/body height (m)2 provides a simple numeric measure of a person's “fatness” or “thinness.” A BMI of 18.5–25 may indicate an optimal weight, a number above 25 may indicate the person is overweight, and a number above 30 suggests the person is obese. A BMI lower than 18.5 suggests the person is underweight.24

Statistics

All data were stored in a customized database (applying SPSS for Windows Version 13) for description and statistical analyses. SF-36 data were scored in accordance with the manual.23 An independent sample t test was used to compare the MFS group with the GP group. The results were additionally checked by using the Mann-Whitney U test. To assess the size of the difference between the MFS group and the GP group, standard difference scores (s-scores) were calculated. The mean scores of the Marfan group were subtracted from the mean scores of the GP, and the differences were divided by the standard deviation of each scale in the GP. The values of the s-scores were interpreted according to Cohen's effect size index, in which <0.2 implies a small difference, 0.5–0.8 a moderate, and >0.8 a large difference.25

Linear regression analyses were used to assess the relationships of each of the eight subscales of the SF-36 scores to demographic variables, MFS symptoms, and fulfillment of MFS criteria as independent variables. For each subscale, multiple regression models were applied, using age, gender, and the factors showing significant correlations in the linear models as independent variables.

P values <0.05 were adopted as significant.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study group. The most frequently fulfilled major criterion was the dural criterion, followed by the family/genetic, ocular, cardiovascular, and skeletal criteria. Table 2 visualizes the 105 participants in the Norwegian Marfan study,26 indicating which major criteria fulfilled and organ systems involved in the individual participant.

Table 3 shows the mean scores in all eight subscales of SF-36 for the MFS group and the GP group. There were large differences between the groups, with lower scores on all four physical health subscales, and on VT and SF on the MH subscales, with effect sizes of 0.81–1.52, the latter value in the subscale of GH. There were moderate differences in the same direction between the groups for the last two subscales within the mental domain, namely MH and role emotional, with effect sizes of 0.53 and 0.68, respectively.

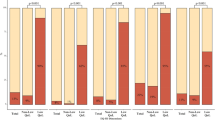

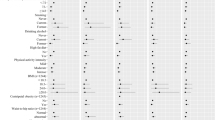

The differences in HRQOL found between the MFS group and other groups of persons with chronic disorders, and between our MFS group and findings in other studies concerning MFS, are presented graphically by using the mean scores for each subscale (Figs. 1 and 2), and further by using the mean MCS and PCS scores (Fig. 3).

Figure 1 shows the comparison between the eight subscales of the SF-36 for the MFS sample and for the four chosen chronic disorders. Persons with MFS showed lower HRQOL both in physical and mental subscales compared with groups of persons with uveitis, CF, and HCM. Compared with the group with BS, the MFS group scored higher on all subscales except VT, for which the two groups were similar.

Figure 2 shows comparisons between the SF-36 subscale scores for our MFS sample and results from the two previously presented studies on MFS (Fig. 2). In Figure 3, the mean MCS and mean PCS for the MFS sample are compared with those in the articles reporting component summaries.

Table 4 reports the final multiple regression models including age, gender, and the variables with significant contributions to the variances.

In the final models, there were no significant relationships between gender and any of the eight subscales of SF-36. This study also showed no significant relationship between the SF-36 score and BMI. Increasing age was associated with increasing pain and decreasing physical function. Fulfilling an increasing number of major criteria was associated with better scores for role emotional and social function, while having a first-degree relative independently fulfilling the Ghent criteria and fulfilling the family/genetic major criterion was associated with better scores for role emotional. Finally, fulfilling the ocular major criterion was associated with higher scores for GH and physical function.

DISCUSSION

In this sample of persons with MFS, we found, as expected, significantly decreased HRQOL on all SF-36 subscales compared with results from a gender- and age-matched control group drawn from the Norwegian general population, confirming Hypothesis 1. However, the expected associations between the scores for the eight subscales of SF-36 and the chosen variables were not found, refuting Hypothesis 2.

The differences between scores in the MFS sample and the healthy controls concerning the physical health subscales, VT, and SF were large, whereas moderate differences were found in MH and role emotional subscales.

Comparison groups

All five disease groups displayed a similar pattern for the physical subscales, with lower GH and role physical scores. Conversely, the SF-36 profile of the GP was characterized by high scores on all physical subscales.

With the exception of the BS group, all groups, including the GP, showed a marked dip in VT scores, when compared with the other MH subscales. The lowest subscale score in the BS sample was the role emotional subscale.

In this study, persons with MFS scored somewhat lower than all other groups except the BS sample for SF and lower than all groups on the VT subscale. The low VT score may reflect the frequently reported complaint of fatigue and reduced physical endurance among persons with MFS.7

On the physical subscales, persons with MFS reported more BP and had worse scores for role physical compared with groups with uveitis, CF, and HCM but better scores than the BS group. In our population, 53% of the persons fulfilling the Ghent criteria had a Beighton score ≥4. Thus, joint hypermobility could only explain part of the elevated pain level reported. However, it was a surprising finding that persons with MFS had worse scores for role physical than persons with CF, a disease that is normally judged as far more serious than MFS regarding reduced physical function and even shorter life expectancy than in the MFS population. Although the life expectancy in the patients with CF are shorter, it may be speculated that the daily care necessary might be supportive, whereas the patients with MFS are left to their own, in daily life.

Both Fusar-Poli et al.,11 who investigated persons with MFS only, and Verbraecken et al.,12 who addressed sleeping problems in persons with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and MFS, report scores for all eight subscales of SF-36. Fusar-Poli et al.11 also report mental and physical component summaries. Foran et al.,2 who investigated persons with MFS and dural ectasia, report the component summaries only. Because >90% of our study population had dural ectasia, comparison with the results of Foran et al. seems relevant.

In all MFS studies cited, SF-36 profiles similar to those found in the comparison groups reported earlier (Fig. 2) were observed; the most deviant finding is the low score for VT in our study sample. For physical scores, our study sample had the lowest scores in all subscales except physical function.

Regarding the component summaries, our findings for MCS are comparable with the results obtained by Fusar-Poli et al.11 and Foran et al. For PCS, our results are comparable with the findings of Foran et al. but lower than those of Fusar-Poli et al.11

The interpretations of the findings differ between the respective studies. Fusar-Poli et al.11 found reduced scores on the mental subscales and approximately normal scores on the physical subscales, when compared with the general Italian population. In their interpretation of these findings, they refer to articles reporting a correlation of MFS to psychiatric syndromes and neuropsychological deficits (learning disabilities). Clinically, we have not found an increased prevalence of depression and schizophrenia in the Norwegian MFS population. However, in our pilot study,27 in which we explored the prevalence of fatigue, psychological distress, and neuropsychological function in MFS, we found high levels of fatigue, correlating to increased psychological distress.

Verbraecken et al.12 claim that emotional or psychological problems might not be important for sleep disturbances in persons with MFS, because scores for emotional problems were normal; even though they found significantly lower scores for mental function compared with the controls. A significantly low score for pain was also reported.

It may be speculated whether the discrepancies between the studies reflect differences in recruiting routines, national differences in perception or communication of function and pain, or real differences in HRQOL. The other studies recruited their participants through specialist institutions. Our study sample represents a rather unselected group of people fulfilling the Ghent criteria, recruited through all relevant specialities, the National Resource Centre and the patient organization.

Associations of HRQOL with demographic variables and MFS symptoms and criteria

Few associations were found between HRQOL and other variables. Of the observed associations, the effect of increasing age on physical function and role physical are well known. However, although in most studies, women have shown lower scores on SF-36, we found no gender difference in our MFS sample, which may perhaps be considered to suggest that the male participants were more seriously afflicted than the females. In our study, we found higher prevalence of fulfilling major cardiovascular criteria in men (22/31) than in women (24/56).28

The effect of fulfilling an increasing number of major criteria, of positive family/genetic major, and of having a first-degree relative independently fulfilling Ghent criteria may at first sight seem surprising.

A high degree of severity in MFS may be understood as fulfilling many major criteria.15 We actually expected that persons fulfilling many major criteria would be found to have more greatly reduced HRQOL than those fulfilling few major criteria. However, in a study on postpolio syndrome, persons with severe polio sequelae were found to have positive consequences through identification with the diagnosis, compared with lesser polio sequelae.29 Analogously, it may be easier to adapt to the “Marfan role” when the diagnosis is unquestionable or if a close relative also has the diagnosis.

The associations between (sub)luxated lenses and an increased level of GH and physical function are unexpected. However, Comeglio et al.30 reports that persons with ectopia lentis more often have a FBN1 mutation in exons 1–15 compared with persons with mutations in the other exons and that mutations found in exons 1-15 and exons 59-65 are associated to ectopia lentis and incomplete MFS, defined as persons not fulfilling the Ghent criteria. In our material, however, the frequency of ectopia lentis among the persons with mutations in exons 1–15 is lower than the frequency of ectopia lentis among persons with mutations in the other exons (see Ref. 15. Table IIA). In addition, all persons fulfilling the Ghent criteria in our study, fulfilling the major ocular criterion (ectopia lentis), fulfilled at least three major criteria (Table 2). Furthermore, no associations were found between any of the subscales of SF-36 and visual acuity.

The lack of correlations of substantial explanatory value between the subscales of SF-36 and most of the independent variables was surprising. Contrary to our expectations, we found no association between the subscales of SF-36 and important physical symptoms such as aortic pathology, dural ectasia, or fulfillment of skeletal major criteria.

Three different, but potentially reconcilable, explanations for this result may be proposed. First, the Ghent criteria are complex, demanding at least two major criteria be fulfilled and a third organ system involved. Hence, “fulfilling the Ghent criteria” and “a single major criterion” are hardly independent concepts. Because all reported persons do fulfill the Ghent criteria, the lack of correlations between these criteria and HRQOL may be a natural consequence.

Second, the diagnosis implies pathologic effects in at least three organ systems. The perceived consequences vary considerably through mechanisms that may not be caused by the pathology described in the diagnostic criteria. The SF-36 scores might instead reflect the total burden of the syndrome rather than the burden of any specific single symptom. Fatigue and reduced physical endurance27 together with adverse effects on daily life, such as coping with stigmata,6 and pain,2,12 fatigue,2 aspects of reproductive planning,10 adherence to medication,31 and restrictions in physical activity32 may play a role. Moreover, the relatively low HRQOL scores might reflect the burden of living with a lifelong, potentially disabling and potentially life-shortening disease, where the needs for physical restrictions and medication are usually not based on perceptions of symptoms but on advice from medical specialists.

Third, the HRQOL in MFS may be related to an underlying, general biological mechanism that is associated with disorders of connective tissue such as MFS and is potentially related to the degree of severity of the disease. This might be in accordance with the finding of transforming growth factor β oversignaling as the biochemical cause of most MFS pathology found in studies of mice with MFS.33

Limitations of our study

The study cohort is skewed for gender, with a surplus of women. Although recruited from all specialities, from the National Resource Centre, and from the patient union, the sample may be too small to represent all variants of MFS. There is a general discussion about what SF-36 measures and the usefulness of the SF-3634; however, we chose this widely used tool to have comparisons to other well-described cohorts, including the general population.13

CONCLUSION

Persons with verified MFS have a lower HRQOL as measured by all eight subscales of SF-36, compared with the Norwegian general population; the physical subscales were somewhat more affected than the mental ones.

The level of reduction of the SF-36 scores is comparable with that found in other groups of persons with serious chronic disorders.

Compared with earlier reports on SF-36 in MFS, our study population showed lower scores for VT, BP, and role physical.

Several factors may explain the lack of significant correlations of substantial explanatory value between the subscales of SF-36 and demographic variables, MFS symptoms, and MFS criteria. Possible examples are the complexity of the Ghent criteria, the impact of the total burden of the diagnosis, the effect of restrictions and medication prescribed prophylactically by professionals, and not used symptomatically, to alleviate bodily perceptions, and an inborn effect of transforming growth factor beta receptor oversignaling.

Further studies on groups of adults with verified MFS should be pursued to explore the consequences of living with MFS.

References

De Paepe A, Devereux RB, Dietz HC, Hennekam RC, Pyeritz RE . Revised diagnostic criteria for the Marfan syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1996; 62: 417–426.

Foran JR, Pyeritz RE, Dietz HC, Sponseller PD . Characterization of the symptoms associated with dural ectasia in the Marfan patient. Am J Med Genet A 2005; 134A: 58–65.

Milledge J, Ades L, Cooper M, Jaumees A, Onikul E . Severe spontaneous intracranial hypotension and Marfan syndrome in an adolescent. J Paediatr Child Health 2005; 41: 68–71.

Schievink WI, Gordon OK, Tourje J . Connective tissue disorders with spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leaks and intracranial hypotension: a prospective study. Neurosurgery 2004; 54: 65–70.

Lacassie HJ, Millar S, Leithe LG, et al. Dural ectasia: a likely cause of inadequate spinal anaesthesia in two parturients with Marfan's syndrome. Br J Anaesth 2005; 94: 500–504.

Peters K, Apse K, Blackford A, McHugh B, Michalic D, Biesecker B . Living with Marfan syndrome: coping with stigma. Clin Genet 2005; 68: 6–14.

Giske L, Stanghelle JK, Rand-Hendrikssen S, Strom V, Wilhelmsen JE, Roe C . Pulmonary function, working capacity and strength in young adults with Marfan syndrome. J Rehabil Med 2003; 35: 221–228.

Peters KF, Kong F, Horne R, Francomano CA, Biesecker BB . Living with Marfan syndrome I. Perceptions of the condition. Clin Genet 2001; 60: 273–282.

Gray JR, Bridges AB, West RR, et al. Life expectancy in British Marfan syndrome populations. Clin Genet 1998; 54: 124–128.

Peters KF, Kong F, Hanslo M, Biesecker BB . Living with Marfan syndrome III. Quality of life and reproductive planning. Clin Genet 2002; 62: 110–120.

Fusar-Poli P, Klersy C, Stramesi F, Callegari A, Arbustini E, Politi P . Determinants of quality of life in Marfan syndrome. Psychosomatics 2008; 49: 243–248.

Verbraecken J, Declerck A, Van de Heyning P, De Backer W, Wouters EF . Evaluation for sleep apnea in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and Marfan: a questionnaire study. Clin Genet 2001; 60: 360–365.

Loge JH, Kaasa S . Short form 36 (SF-36) health survey: normative data from the general Norwegian population. Scand J Soc Med 1998; 26: 250–258.

Lundby R, Rand-Hendriksen S, Hald JK, et al. Dural ectasia in Marfan syndrome: a case control study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2009; 30: 1534–1540.

Rand-Hendriksen S, Tjeldhorn L, Lundby R, et al. Search for correlations between FBN1 genotype and complete Ghent phenotype in 44 unrelated Norwegian patients with Marfan syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2007; 143: 1968–1977.

Rand-Hendriksen S, Lundby R, Tjeldhorn L, et al. Prevalence data on all Ghent features in a cross-sectional study of 87 adults with proven Marfan syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 2009; 17: 1222–1230.

Tjeldhorn L, Rand-Hendriksen S, Gervin K, et al. Rapid and efficient FBN1 mutation detection using automated sample preparation and direct sequencing as the primary strategy. Genet Test 2006; 10: 258–264.

Schiffman RM, Jacobsen G, Whitcup SM . Visual functioning and general health status in patients with uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol 2001; 119: 841–849.

Cox S, O'Donoghue AC, McKenna WJ, Steptoe A . Health related quality of life and psychological wellbeing in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart 1997; 78: 182–187.

Goldbeck L, Schmitz TG . Comparison of three generic questionnaires measuring quality of life in adolescents and adults with cystic fibrosis: the 36-item short form health survey, the quality of life profile for chronic diseases, and the questions on life satisfaction. Qual Life Res 2001; 10: 23–36.

Tanriverdi N, Taskintuna Duru C, Ozdal P, Ortac S, Firat E . Health-related quality of life in Behcet patients with ocular involvement. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2003; 47: 85–92.

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD . The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30: 473–483.

Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Gandek B . SF-36 Health Survey; Manual & Interpretation Guide. Lincoln, Quality Metric Incorporated, 2005.

Eknoyan G . Adolphe Quetelet (1796–1874)—the average man and indices of obesity. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008; 23: 47–51.

Cohen J . Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences—the effect size. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum associates, 1988.

Rand-Hendriksen S, Lundby R, Tjeldhorn L, et al. Prevalence data on all Ghent features in a cross-sectional study of 87 adults with proven Marfan syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 2009; 17: 1222–1230.

Rand-Hendriksen S, Sorensen I, Holmstrom H, Andersson S, Finset A . Fatigue, cognitive functioning and psychological distress in Marfan syndrome, a pilot study. Psychol Health Med 2007; 12: 305–313.

Rand-Hendriksen S, Lundby R, Tjeldhorn L, et al. Prevalence data on all Ghent features in a cross-sectional study of 87 adults with proven Marfan syndrome. Erratum. Eur J Hum Genet 2009; 17: 1526.

Maynard FM, Roller S . Recognizing typical coping styles of polio survivors can improve re-rehabilitation. A commentary. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1991; 70: 70–72.

Comeglio P, Johnson P, Arno G, et al. The importance of mutation detection in Marfan syndrome and Marfan-related disorders: report of 193 FBN1 mutations. Hum Mutat 2007; 28: 928.

Peters KF, Horne R, Kong F, Francomano CA, Biesecker BB . Living with Marfan syndrome II. Medication adherence and physical activity modification. Clin Genet 2001; 60: 283–292.

Pyeritz RE . The Marfan syndrome. Annu Rev Med 2000; 51: 481–510.

Neptune ER, Frischmeyer PA, Arking DE, et al. Dysregulation of TGF-beta activation contributes to pathogenesis in Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet 2003; 33: 407–411.

Horner-Johnson W, Krahn GL, Suzuki R, Peterson JJ, Roid G, Hall T . Differential performance of SF-36 items in healthy adults with and without functional limitations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010; 91: 570–575.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by (South-) Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (Helse (Sør-)Øst RHF); TRS, a National Resource Centre for Rare Disorders; the Stokbaks Heart Foundation; and the Kirkevoll Memory Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rand-Hendriksen, S., Johansen, H., Semb, S. et al. Health-related quality of life in Marfan syndrome: A cross-sectional study of Short Form 36 in 84 adults with a verified diagnosis. Genet Med 12, 517–524 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ea4c1c

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ea4c1c

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The Musculoskeletal Manifestations of Marfan Syndrome: Diagnosis, Impact, and Management

Current Rheumatology Reports (2021)

-

Influence of response shift and disposition on patient-reported outcomes may lead to suboptimal medical decisions: a medical ethics perspective

BMC Medical Ethics (2019)

-

Marfan syndrome in adolescence: adolescents’ perspectives on (physical) functioning, disability, contextual factors and support needs

European Journal of Pediatrics (2019)

-

Quality of life in adults with lymphedema cholestasis syndrome 1

Health and Quality of Life Outcomes (2018)

-

Executive function and quality of life in individuals with Marfan syndrome

Quality of Life Research (2018)