Abstract

Purpose: There is no consensus on how best to communicate risk in breast cancer genetic counseling. We studied risk communication in completed series of counseling visits and assessed associations with counselees' postcounseling risk perception and satisfaction.

Methods: Pre- and postcounseling questionnaires and videorecordings of all visits were available for 51 affected and unaffected women from families with no known BRCA1/2 mutation, who fulfilled criteria for DNA testing. We developed a checklist for assessing risk communication and counselors' behaviors.

Results: General risks were mainly communicated in initial visits, while counselee-specific risks were discussed mainly in concluding visits. The risks discussed most often were conveyed only numerically or qualitatively, and most were only stated positively or negatively. Counselors regularly helped counselees to understand the information, but seldom built on counselees' pre-existing perspective. Counselees' breast cancer risk perception after counseling was unrelated to whether this risk had been explicitly stated. The number of general risks discussed was negatively associated with counselees' satisfaction about counseling.

Conclusion: Findings suggest that counselors' authority prevails over mutuality with individual counselees, in their communication about risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The emphasis in cancer genetic counseling is on enhancing accurate and useful risk perceptions1 as a means to promoting appropriate risk management.2 In the case of breast cancer genetic counseling, various probability estimations are implicated, including breast cancer risk in the general population, estimation of whether the breast cancer is hereditary, breast cancer risk for mutation carriers, and the risk for counselee or relatives to develop or redevelop breast or ovarian cancer. Counselors may communicate more or less of these risks to counselees. One of the few studies on actual risk communication in breast cancer genetic counseling suggests that in individual initial visits, counselors provide only a few facts about risk.3 Counselees' persisting inaccurate risk perceptions after counseling4–8 underlines the need for more insight into actual risk communication, and what is conveyed during the total counseling process rather than during initial visits only.

There is no consensus about ‘best practices’ for how health care providers should present health-related risks9,10 and there is still debate about what form of presentation counselees can most easily understand.2,9,11 Studies assessing the preferred form of risk presentation among women counseled for suspected hereditary breast cancer found a majority having a preference for a specific format.7,12 No clear preference was agreed upon though,7 suggesting that counselors should convey risks in various formats. Moreover, clinical risk communication can be viewed as a two-way process.13 To be able to inform counselees in a personally meaningful way means that their pre-existing risk perceptions,14,15 risk beliefs,16 and preferred risk format have to be identified first.

The aim of this study is to characterize actual risk communication during completed series of counseling visits in affected and unaffected women at risk of hereditary breast cancer. We also aimed to assess whether risk communication was related to counselees' postcounseling accuracy of risk perception and satisfaction. We expected that counselees who were given a personalized cancer risk in any of their visits would be more accurate in their risk perceptions and more satisfied with the information given about their own risk than counselees who received general risks only.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Consecutive counselees were recruited at the Department of Medical Genetics, University Medical Centre, Utrecht, the Netherlands, from March 2001 until August 2003.17 Inclusion criteria were being 18 years or older and being the first in their family to seek cancer genetic counseling. For the present study, secondary analyses were performed on women seeking counseling for suspected hereditary breast cancer and who had an indication for diagnostic DNA testing. A DNA test was offered to counselees or their affected relatives when they had an a priori chance ≥10% of carrying a BRCA1/2 mutation.18

Series of initial, follow-up, and concluding visits

Counseling usually consists of two visits. During the initial visit, the counselee's pedigree and details about family history of cancer are discussed. If there is an indication for DNA testing after the initial visit and counselees proceed with testing, a blood sample is drawn from the counselee or relative. Follow-up (i.e., intermediate) visits may be arranged to discuss pedigree data that are not available during the initial visit. In the concluding visit, the counselee is told the test results and is given breast and ovarian cancer risk estimates. If a BRCA1/2 mutation has been detected, risk figures are based on Antoniou et al.19 If not, breast cancer risk is based on Claus et al.20 and ovarian cancer risk is based on Stratton et al.21 Screening recommendations are also made. All counselees receive a written summary after their initial and concluding visits.

A consultation is ordinarily conducted by one counselor, although if the counselor is in training, a clinical geneticist may also be present. All the counselors providing cancer genetic counseling at the clinic during the study period participated: Five clinical geneticists (4 female, 1 male), 3 residents in clinical genetics (2 female, 1 male; 2 finishing training) and 5 genetic nurses (all female; 4 finishing training). They all completed a postcounseling questionnaire. Counselors were aged 30–46 years (M = 38.6; SD = 5.2).

Procedure

The main study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the UMC Utrecht. The procedure of approaching eligible counselees has been described elsewhere.22 Respondents were asked to complete an informed consent form and a precounseling questionnaire in the week before their first visit. Initial, follow-up, and concluding visits were videotaped. After the concluding visit, the counselor handed out a postcounseling questionnaire and asked the counselee to complete it within a day and post it to the research institute.

Measures

The pre-visit questionnaire assessed socio-demographics and family history of cancer. Information on whether counselees were affected with breast cancer was collected from their medical file.

Perceived risk of cancer was assessed pre- and postcounseling using three visual analogue scales. Endpoints of the scales were 0 and 100%. Counselees were asked to rate separately their perceived risk of hereditary cancer running in the family, that they had inherited susceptibility to cancer, and that they would develop or redevelop breast cancer in the future. Postcounseling, the counselors rated similar numerical scales with their professional estimated risk for the counselee.

Counselees' need for information on their own risk of cancer was assessed precounseling using three 4-point Likert-type scaled items (α = 0.83) as part of a counselee-centered instrument aimed at assessing needs, the QUOTE-geneca.22 Postcounseling, identical items were used to measure perceived need fulfillment (α = 0.86). High mean scores (range, 1–4) indicate a high importance/fulfillment.

Satisfaction with counseling was assessed using eight items (α = 0.94). Sum scores ranged from 8 to 80, with high scores indicating high satisfaction.23

Verbal risk communication was rated using a checklist adapted from Lobb et al.3,7 for which a detailed coding manual was developed. It was designed to code (yes/no) whether the following risks were mentioned: 1) general population probabilities of breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and hereditary breast cancer, i.e., proportion of breast cancer in the general population caused by a BRCA1/2 mutation; 2) BRCA1/2-related probabilities of breast cancer, ovarian cancer, detecting a BRCA1/2 mutation with a diagnostic DNA test, inheriting or passing on a mutation, and carrying a de novo BRCA1/2 mutation; and 3) counselee-specific probabilities of breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and identifying a mutation in the counselee's family (Table 2). In contrast to Lobb et al.,7 counselees' hypothetical cancer risks if a mutation were detected were coded as general BRCA1/2-related risks.

Several aspects of risk presentation format were noted, including: whether it was a numeric (frequency, percentage, population comparison, proportion) or a qualitative risk (descriptive word, risk category); time horizon (lifetime risk, age-related risk, risk for a specific period); and positive/negative framing (i.e., positive, probability of a favorable outcome vs. negative, probability of harm). For each risk mentioned, who took the initiative (counselor vs. counselee or companion) was also coded.

We coded whether counselors asked counselees about their preferred risk presentation format and whether, and at whose initiative, counselee risk perceptions were mentioned. We defined the extent to which the counselor followed on from a counselee's existing perspective as the sum of times counselees stated their risk perceptions, counselors checked counselees' existing knowledge about breast cancer genetics, and checked whether counselees already knew what they were being told. We defined the extent to which counselors facilitated counselees' comprehension as the sum of times counselors checked counselees' understanding, invited questions, and used graphs (Table 4). Finally, a record was kept of whether a second counselor was present during the whole or part of the visit.

Coding reliability

Two coders were trained. Inter- and intraobserver reliability were assessed with completed series of visits of five (10%) randomly selected counselees. Variables with kappa scores below 0.20 (N = 3) were left out of the analyses (i.e., population risk of breast cancer by age, probability that counselee has inherited a BRCA1/2 mutation, and counselee's perceived risk of carrying a mutation). Inter- and intrarater mean kappa scores were respectively 0.83 (range, 0.40–1.0) and 0.87 (range, 0.27–1.0), indicating very good agreement after correcting for chance.24 Pearson correlations and intraclass coefficients (ICCs) were computed for frequency variables (N = 5). Mean inter- and intrarater correlations were 0.80 (range, 0.65–0.95; ICC: 0.60–0.74) and 0.89 (range, 0.66–1.0; ICC: 0.64–1.0), respectively.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the risks communicated and who took the initiative. Following Evans et al.,25 counselees' perception of own cancer risk was defined as accurate if it fell within a range 50% lower to 50% higher than the counselors' estimate. Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the association between the accuracy of post-visit breast cancer risk perception and a) (the manner of) stating counselees' breast cancer risk and b) the total number of general and counselee-specific risks expressed. T-tests for independent samples were used to assess whether need fulfillment was related to communicating counselees' own cancer risk and having counselees expressing their risk perceptions during counseling. Pearson correlations were used to assess whether need fulfillment and/or satisfaction with counseling were related to the number of general risks, the number of counselee-specific risks, and the number of counselee-specific relative to general risks (i.e., the proportion of counselee-specific compared to general risks) communicated; and whether satisfaction was related with the extent to which counselors followed on from counselees' existing perspective and facilitated their comprehension.

RESULTS

Counselees

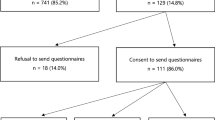

In the main study, baseline questionnaire data were available for 200 counselees. Ninety-one out of 200 (46%) counselees were female, sought counseling for suspected hereditary breast cancer, and fulfilled criteria for DNA testing.22 Three counselees did not return to the clinic for a concluding visit and for one counselee a DNA test result from a deceased parent was already available at the initial visit. For 71 (82%) women, all the visits they had at the clinic had been recorded and for 51 (59%) also postcounseling questionnaire data were available for analysis. Counselee characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Consultations

In total 102 recordings were available for 51 counselees; 50 pertained to initial visits (2 related counselees were seen together), 45 to second visits, 6 to third visits, and 1 to a fourth visit. Six of the 51 counselees were seen once and 39 were seen twice. Five counselees had three visits and one had four.

Overall, 84 (82%) visits were conducted by 1 counselor. When during counseling 2 counselors had been present in any of the visits, more different general risks were stated (M = 8.6 vs. 7.2, t = -2.55, P = 0.014) and counselees' need fulfillment and satisfaction were lower (M = 2.92 vs. 3.37, t = 2.62, P = 0.012, and M = 68.62 vs. 58.62, t = 4.93, P = 0.000, respectively). No differences were found in number of counselee-specific risks expressed, nor in accuracy of counselees' risk perceptions, extent to which counselors followed on from counselees' existing perspective, or extent to which counselors facilitated counselees' comprehension.

General and counselee-specific risks

Table 2 lists the various general (i.e., population and BRCA1/2-related) risks and counselee-specific risks stated, along with who took the initiative for a discussion. Risks presented in the follow-up visits of the counselees seen three or four times are not shown separately because of the small number (N = 7) of these intermediate visits. As counselee-specific cancer risk information becomes available only after medical information, including DNA test results, has been gathered, general risks, as expected, were mostly communicated during initial visits while counselee-specific risks were communicated in concluding visits. If stated, the counselee-specific chance of identifying a mutation in her family was communicated in the initial visit, at the stage when DNA testing was offered. The initiative for communicating risks lay almost exclusively with counselors.

Overall, 7.6 (range, 3–11; SD = 2.0) different general, i.e., population and BRCA1/2-related, risks were discussed during counseling. The estimations cited most often were those relating to the general population risk of breast cancer and the percentage of breast cancer caused by BRCA1/2 mutations, while the general population estimation of ovarian cancer risk by age was never mentioned (Table 2). The proportion of the population with breast cancer caused by a BRCA1/2 mutation was conveyed to 79% of the affected women and to 53% of the unaffected women. The probability of detecting a mutation, i.e., the (limitations to the) capabilities of current DNA technology, was conveyed to 82% of the affected women and to 71% of the unaffected women. Even though these women all fulfilled the criteria for DNA testing, not all were told about this probability.

Overall, 1.3 (range, 1–3; SD = 0.9) counselee-specific risks were expressed during counseling (Table 2). The counselee's risk of developing a primary or contralateral breast cancer, depending on previous cancer history, was communicated to 82% of unaffected women, compared to 38% of affected women. The counselee's risk of ovarian cancer was communicated to 47% of unaffected women and to 50% of affected women.

Risk presentation formats

Table 3 shows that of the eight risks that were communicated in a majority of the visits, four were mostly expressed either only numerically or only qualitatively. Population risk of breast cancer was expressed only numerically. Moreover, most risks were expressed only in terms of probability of harm, e.g., probability of developing cancer or of carrying a BRCA1/2 mutation, instead of (also) in terms of the probability of not developing cancer and of not carrying a BRCA1/2 mutation. One notable exception was the probability of detecting a BRCA1/2 mutation. This was given as the probability of the diagnostic DNA test detecting a mutation (i.e., positively) in 60% of the visits, that is, as the test giving a definite answer about genetic predisposition.

The counselee's risk of cancer, as communicated in concluding visits, was stated only qualitatively for at least half of the counselees and predominantly in terms of developing the disease (Table 3).

Age-related breast and ovarian cancer risks due to a BRCA1/2 mutation were mentioned with less than one-fifth of the counselees (Table 2). Likewise, the time horizon of the general and counselee-specific breast and ovarian cancer risks that were communicated (Table 2) was not expressed for six of these. It was most often stated for the population risk of breast cancer (i.e., in 39% of expressions of this risk). In all but one instance, the time horizon stated was a lifetime.

Counselees' risk perceptions and counselors' facilitating behaviors

Table 4 shows that very few counselees expressed how they themselves perceived either the probability of hereditary cancer running in their family, or their own risk of developing or redeveloping breast cancer. The initiative to verbalize both these perceptions lay most often with counselees (data not shown).

Table 4 further shows that counselors never asked about counselees' preferred risk presentation format, asked only a few counselees about their existing genetic knowledge, or whether counselees already knew the medical information being provided. In contrast, counselors often facilitated comprehension: they checked counselees' understanding and invited questions from most of the counselees. If so, on average they checked 2.1 times counselees' understanding (range, 1–3; SD = 1.2) and invited 2.6 questions (range, 1–6; SD = 1.5). In initial visits, counselors used diagrams to illustrate the medical information for most counselees. A diagram of the family's pedigree was used in almost half of the concluding visits.

Risk communication and accuracy of counselees' breast cancer risk perceptions

Regarding their risk of developing breast cancer, precounseling 48% of counselees (24/50; 1 missing value) expressed an accurate risk perception, whereas postcounseling 51% (23/45; 6 missing values) was accurate. If we controlled for precounseling accuracy, the level of postcounseling accuracy was unrelated to whether counselees' personal breast cancer risk had been expressed (B = 1.11, SE = 0.70). In the counselees with whom their own risk of cancer had been communicated (N = 27; 5 missing values for accuracy), accuracy was unrelated to how this risk was stated (i.e., qualitatively and/or numerically; B = 0.29, SE = 0.89). In the whole sample, post-visit accuracy was also unrelated to the total number of general and counselee-specific risks expressed during counseling. However, accuracy was related to the proportion of counselee-specific versus general risk information stated: the more personalized compared to general risks were communicated, the more accurate counselees' post-visit risk perceptions were (B = 0.08, SE = 0.04, P = 0.042).

Fulfillment of need for information on own risk and satisfaction with counseling

Almost all counselees (47/50) considered information regarding their own risk of cancer as important to very important at the precounseling stage. Postcounseling fulfillment of this need was related to none of the risk communication variables. Satisfaction was negatively associated with the number of general risks stated during counseling (Pearson r = -0.37, P = 0.011). Satisfaction was not related to the other risk communication variables, or to counselors' involving and facilitating behaviors.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess risk communication in a series of completed breast cancer genetic counseling visits in affected and unaffected women at high-risk of hereditary breast cancer. It reflects the daily practice in one of the nine Dutch familial cancer clinics.

Results on the types of general risks most often communicated during counseling replicate and extend those reported by Butow and Lobb3 for initial breast cancer genetic counseling visits in an Australian sample of affected and unaffected women. Notably, our results suggest that the more general risks were expressed, the less counselees felt satisfied about the counseling. Lowered satisfaction may possibly be due to excessive, not so much appreciated information-giving. In this study, the number of counselee-specific risks communicated was unrelated to counselees' satisfaction. Further research is necessary to assess whether counselees may indeed prefer to discuss information that is specifically relevant to them. The total number of different risk expressions was unrelated to postcounseling accuracy of risk perceptions, as Lobb et al.7 found after initial visits. Notably, postcounseling accuracy was not related to the absolute number of general or counselee-specific risks that were stated, but it was associated with the proportion of counselee-specific versus general information. Put differently, receiving relatively more personalized risk information appears to facilitate comprehension and/or recall of one's own risk. These findings may imply that the amount of general and counselee-specific information should be more in balance. Counselees may otherwise become overwhelmed with risk information in which personalized values are lost for comprehension.

It was surprising that not all women were given an estimate of their own risk of breast and ovarian cancer during any of their counseling visits, even after the results of DNA testing were available. One-fifth of unaffected and two-thirds of affected women were never told their risk of breast cancer or of getting a second primary cancer. Butow and Lobb3 found similar figures. In affected women in whom no BRCA1/2 mutation was detected, this risk is difficult to indicate. As opposed to carriers who have a strongly elevated risk of developing a contralateral cancer,26 the incidence of contralateral cancer in breast cancer patients in general is only 0.4–1% per year.27 Counselees' inaccurate breast cancer risk perceptions may thus, at least partly, be explained by this risk not being communicated. Counselee-specific ovarian cancer risk was expressed to only half of the women. Counselors possibly did not expect most of these counselees to be at increased risk. However, if counselees have learned that breast and ovarian cancer are associated in cases of genetic predisposition, they may want to know their own risk, even if it is not increased.

Contrary to our expectations, both postcounseling accuracy of counselees' breast cancer risk perceptions and fulfillment of their need for information about their cancer risk were unrelated to whether or not their breast cancer risk had been stated. One possible explanation is that only a minority of counselees were invited to reveal how they perceived their risks, offering little opportunity to correct significant over- or underestimations. By initiating the discussion of these perceptions more often, counselors may assess whether they succeed in conveying their estimates and/or may better follow on from counselees' beliefs. In the sample of counselees who expressed how they themselves perceived the probability of hereditary cancer running in their family and/or their own risk of developing or redeveloping breast cancer, 47% had inaccurate breast cancer risk perceptions compared to 50% of counselees who did not state their perceptions. Thus, our assertion is not clearly supported by these data but should be investigated in a larger sample of counselees.

When stated, counselees' cancer risks were expressed at least half of the times in qualitative terms only. This may partly explain counselees' inaccurate breast cancer risk perceptions, assuming that qualitative expressions are more vague than numeric expressions; the small subsample which we assessed did not reveal such an association. Lobb et al.7 found no association between post-visit risk accuracy and whether risks had been communicated both in words and in numbers. Yet Hallowell et al.12 found women who did or did not receive a quantitative estimate of their cancer risk to perceive such numerical descriptors as clarifying risk for both themselves and others. A qualitative presentation format may also explain the lack of association between risk accuracy and whether a counselee's risk was stated, as perceived risk was assessed using a numerical scale and qualitative expressions are variably translated into numbers.28 Further investigation is warranted.

Probabilities of developing cancer were most often framed as the risk for the disease to occur rather than in terms of both developing and not developing cancer. Expressing risks both in words and in numbers, and giving both the probability of developing and not developing the disease, are ways to present risk information in a balanced, nondirective manner. It is also a way to put risks into context and may therefore aid comprehension. More research is needed to assess whether presenting risks in more different ways indeed supports counselees in their comprehension of risk information. As regards a time horizon, there is no evidence for age-related or lifetime risks to be more easily comprehended generally.9,11 Our data revealed that a time horizon was not often stated, and if it was, the risk was stated as a lifetime risk. Our findings suggest that counselors should not assume that counselees will understand time frames consistently,2 so explicitly stating these appears to be a necessary first step.

The probability of detecting a BRCA1/2 mutation was not reported to about one-fifth of the women. Moreover, those who were told were told only in terms of the DNA test actually detecting a mutation, i.e., the test providing a definite answer about genetic predisposition. In the precounseling period, counselees from families with no known mutation often value and expect to learn whether breast cancer in their family is hereditary or not.22,29 Counselors need to explain the limitations of DNA technology in demonstrating heredity. In our sample, only seven women had DNA testing that showed the definite presence (5/7) or absence (2/7) of a mutation. By explicitly stating the probability of not detecting any mutation, counselors may be able to temper expectations.

Contrary to Butow and Lobb's3 findings, counselors never asked for counselees' preferred risk format; from our data it is thus unclear how much the formats used corresponded to counselees' preferences and whether this may facilitate accurate risk perceptions. As regards checking and facilitating counselees' understanding, including inviting questions and using diagrams, our results correspond and extend those of Butow and Lobb's work3 in initial visits. In general, the results suggest that the counselors showed more behaviors aiming at facilitating counselees' understanding of the information provided than at involving them in the interaction. Counselors tended to take the initiative in what risks to convey, to convey these in a uniform manner, and not to involve counselees' perspectives in the interaction. The counselors' authority (i.e., expertise) therefore dominated the visits rather than mutuality and seeking understanding of counselees' views. As regards the communication of risks, counselors apparently followed the teaching model rather than the counseling model of counseling.30 This may contribute to excessive information-giving and is less appropriate for reinforcing counselees' competence and capacity for autonomy.30 Of note, having two counselors conducting the consultation appeared to reinforce the delivery of general risk information and to lower counselees' satisfaction with counseling. These results suggest that especially in these circumstances excessive information-giving may occur.

Limitations

This study was conducted at one genetic center and comprised a relatively small number of counselors, limiting how far we can generalize the results. The overall reliability of the coding scheme appeared satisfactory, although some risk concepts were not reliably coded. One explanation is that risk may be conveyed as a prevalence rather than a probability, two concepts that are closely linked and difficult to distinguish. Another complicating aspect is the distinction between risks relating to counselees and those relating to their relatives.

Thirteen counselors were involved in the study and their individual communication style may have affected risk communication. The limited number of counselees made these data less suitable to an assessment of individual counselor communication style. Where possible, further research should take account of this variance. In addition, in one-fifth of the consultations a second counselor was present during (part of) the visit and this affected risk communication. This variance, albeit limited, should also be taken account of in future studies.

CONCLUSION

Our results suggest that the relatively more personalized risk information is communicated during breast cancer genetic counseling, the more accurate counselees' postcounseling risk perceptions are. The risks presented differed in the initial and concluding visits, suggesting that data on completed series of visits are necessary to provide an adequate description of risk communication in breast cancer genetic counseling. Our findings further indicate that as regards counselees' satisfaction, counselors should not strive so much to provide general risk information. Finally, risk communication may need to become more interactive, including the elicitation and discussion of existing risk perceptions and knowledge, and the presenting of risks in formats according to individual preferences.

References

Biesecker BB . Goals of genetic counseling. Clin Genet 2001; 60: 323–330.

Hopwood P, Howell A, Lalloo F, Evans G, et al. Do women understand the odds? Risk perceptions and recall of risk information in women with a family history of breast cancer. Community Genet 2003; 6: 214–223.

Butow P, Lobb E . Analyzing the process and content of genetic counseling in familial breast cancer consultations. J Genet Couns 2004; 13: 403–424.

Cull A, Anderson ED, Campbell S, Mackay J, et al. The impact of genetic counselling about breast cancer risk on women's risk perceptions and levels of distress. Br J Cancer 1999; 79: 501–508.

Gurmankin AD, Domchek S, Stopfer J, Fels C, et al. Patients' resistance to risk information in genetic counseling for BRCA1/2. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165: 523–529.

Lerman C, Lustbader E, Rimer B, Daly M, et al. Effects of individualized breast cancer risk counseling: a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995; 87: 286–292.

Lobb EA, Butow PN, Meiser B, Barratt A, et al. Women's preferences and consultants' communication of risk in consultations about familial breast cancer: impact on patient outcomes. J Med Genet 2003; 40: E56.

Pieterse AH, Ausems MG, Van Dulmen AM, Beemer FA, et al. Initial cancer genetic counseling consultation: change in counselees' cognitions and anxiety, and association with addressing their needs and preferences. Am J Med Genet 2005; 137: A27–A35.

Julian-Reynier C, Welkenhuysen M, Hagoel L, Decruyenaere M, et al. Risk communication strategies: state of the art and effectiveness in the context of cancer genetic services. Eur J Hum Genet 2003; 11: 725–736.

Rothman AJ, Kiviniemi MT . Treating people with information: an analysis and review of approaches to communicating health risk information. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1999; 25: 44–51.

Watson M, Duvivier V, Wade Walsh M, Ashley S, et al. Family history of breast cancer: What do women understand and recall about their genetic risk?. J Med Genet 1998; 35: 731–738.

Hallowell N, Statham H, Murton F, Green J, et al. 'Talking about chance': The presentation of risk information during genetic counseling for breast and ovarian cancer. J Genet Couns 1997; 6: 269–286.

Edwards A, Elwyn G, Mulley A . Explaining risks: Turning numerical data into meaningful pictures. BMJ 2002; 324: 827–830.

Bottorff JL, Ratner PA, Johnson JL, Lovato CY, et al. Communicating cancer risk information: the challenges of uncertainty. Patient Educ Couns 1998; 33: 67–81.

Stopfer JE . Genetic counseling and clinical cancer genetics services. Semin Surg Oncol 2000; 18: 347–357.

Hopwood P . Psychosocial aspects of risk communication and mutation testing in familial breast-ovarian cancer. Curr Opin Oncol 2005; 17: 340–344.

Pieterse AH, Van Dulmen AM, Ausems MGEM, Beemer FA, et al. Communication in cancer genetic counselling: Does it reflect counselees' pre-visit needs and preferences?. Br J Cancer 2005; 92: 1671–1678.

American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: Genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 2397–2406.

Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, Risch HA, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case Series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet 2003; 72: 1117–1130.

Claus EB, Risch N, Thompson WD . Autosomal dominant inheritance of early-onset breast cancer. Implications for risk prediction. Cancer 1994; 73: 643–651.

Stratton JF, Pharoah P, Smith SK, Easton D, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of family history and risk of ovarian cancer. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998; 105: 493–499.

Pieterse A, Van Dulmen S, Ausems M, Schoemaker A, et al. QUOTE-geneca: development of a counselee-centered instrument to measure needs and preferences in genetic counseling for hereditary cancer. Psychooncology 2005; 14: 361–375.

Pieterse AH, Van Dulmen AM, Beemer FA, Bensing JM, et al. Cancer genetic counseling: communication and counselees' post-visit satisfaction, cognitions, anxiety, and needs fulfillment. J Genet Couns ( in press, 2006).

Dunn G . Design and analysis of reliability studies: the statistical evaluation of measurement errors. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Evans DGR, Blair V, Greenhalgh R, Hopwood P, et al. The impact of genetic counselling on risk perception in women with a family history of breast cancer. Br J Cancer 1994; 70: 934–938.

Verhoog LC, Brekelmans CT, Seynaeve C, Dahmen G, et al. Survival in hereditary breast cancer associated with germline mutations of BRCA2. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 3396–3402.

Fisher ER, Sass R, Fisher B . Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Project for Breast Cancers (protocol no. 4). X. Discriminants for tenth year treatment failure. Cancer 1984; 53: 712–723.

Lobb EA, Butow PN, Kenny DT, Tattersall MH . Communicating prognosis in early breast cancer: do women understand the language used?. Med J Aust 1999; 171: 290–294.

Van Asperen C, Van Dijk S, Zoeteweij MW, Timmermans DR, et al. What do women really want to know? Motives for attending familial breast cancer clinics. J Med Genet 2002; 39: 410–414.

Kessler S . Psychological aspects of genetic counseling. IX. Teaching and counseling. J Genet Couns 1997; 6: 287–295.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pieterse, A., van Dulmen, S., van Dijk, S. et al. Risk communication in completed series of breast cancer genetic counseling visits. Genet Med 8, 688–696 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.gim.0000245579.79093.86

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.gim.0000245579.79093.86

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Head to head randomized trial of two decision aids for prostate cancer

BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making (2021)

-

Communication about genetic testing with breast and ovarian cancer patients: a scoping review

European Journal of Human Genetics (2019)

-

Counselees’ Expressed Level of Understanding of the Risk Estimate and Surveillance Recommendation are Not Associated with Breast Cancer Surveillance Adherence

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2016)

-

Developing patient-friendly genetic and genomic test reports: formats to promote patient engagement and understanding

Genome Medicine (2014)

-

A focus group study on breast cancer risk presentation: one format does not fit all

European Journal of Human Genetics (2013)