Abstract

Purpose

The use of intravitreal vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor medications has widened considerably to include indications affecting females of reproductive age.

Patients and methods

We present our experiences following intravitreal injection of bevacizumab during the first trimester of unrecognised pregnancies in four women.

Results

All our patients were inadvertently exposed to bevacizumab within the first trimester when placental growth and fetal organogenesis take place. There were three cases of pregnancy without complication and one case of complicated pregnancy in which there was a significant past obstetric history.

Conclusion

This case series provides further insights into intravitreal injection of bevacizumab in early pregnancy. There is insufficient information to suggest that such use is safe, nor is there definitive evidence to suggest that it causes harm. We advise that ophthalmologists discuss pregnancy with women of childbearing age undergoing intraocular anti-VEGF injections. Should a woman become pregnant, counselling is needed to explain the potential risks and benefits, and the limited available data relating to the use of these agents in early pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of intravitreal vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor medications has widened considerably to include indications that may affect female patients of reproductive age, particularly diabetic macular oedema (DMO), retinal vein occlusion, and choroidal neovascularisation (CNV) secondary to pathological myopia. As such, this is a potential safety risk. We present our experiences following intravitreal injection of bevacizumab 1.25 mg (IVB) during the first trimester of unrecognised pregnancies in four women.

Case reports

Case 1

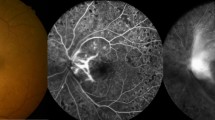

A 20-year-old uniparous female patient presented with idiopathic juxtafoveal CNV. Given the location of the CNV and the poor visual acuity, IVB was considered more likely to improve vision than either photodynamic therapy or thermal laser and she was treated accordingly. One month later, the patient disclosed a positive pregnancy test. By using the date of the last menstrual period, it was calculated that bevacizumab had been given at day 19 of gestation. The pregnancy proceeded without complication but additional fetal well-being scans were performed monthly. A healthy infant of birth weight (BW) 3120 g was born by spontaneous vaginal delivery at 38 weeks. At most recent follow-up of the infant at age 18 weeks, no adverse effects to mother or baby were noted.

Case 2

A 27-year-old myopic female patient presented with CNV associated with punctate inner choroidopathy. IVB was felt to be more likely to provide an increase in visual acuity than either photodynamic therapy or thermal laser and she was treated accordingly. One month later, the patient declared that she was pregnant despite having reported a negative pregnancy test at the time of IVB. The gestational age at the time of IVB was calculated as 21 days. A healthy infant of BW 3860 g was born by spontaneous vaginal delivery at 40 weeks+10 days. At most recent follow-up of the infant at age 6 weeks, no complications to mother or baby were noted.

Case 3

A 20-year-old nulliparous female patient required bilateral vitrectomy and endolaser for severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). She previously had maximal pan-retinal photocoagulation (PRP) treatment. IVB was given to each eye at separate dates. At the time of both injections the patient stated that she was using the combined oral contraceptive pill. However, she became pregnant and it was calculated that the first IVB was administered to her left eye before conception and that the second IVB was administered to her right eye at day 24 of gestation. A healthy infant of BW 3600 g was delivered by forceps at 38 weeks. At the most recent follow-up, 11 months after birth, no adverse effects to mother or infant were recorded.

Case 4

A 25-year-old uniparous woman with a past history of both hypertension and requirement of caesarean section (CS) for fetal distress presented with bilateral PDR and neovascular glaucoma. After maximal PRP bilaterally, she was treated with IVB into each eye. A positive pregnancy test was later disclosed. It was calculated that the last IVB was administered at gestation of 20 days and the other two IVB were given before conception. Urgent CS at 29 weeks was required for preeclampsia.

The 1260-g infant required intubation for initial bradycardia and respiratory failure. A period of ventilation and supplemental oxygen was required for respiratory distress syndrome and pulmonary haemorrhage. Mild pulmonary stenosis and intraventricular cerebral haemorrhage were observed. Blood transfusion for abnormal clotting and for anaemia of prematurity was required. At most recent follow-up at 17 weeks after birth, there were no additional adverse effects to mother or baby.

Discussion

The manufacturers of bevacizumab advise that the drug may cause fetal harm based on the results from reproductive animal studies in which the animals were treated with up to 12 times the recommended intravenous (IV) dose during the first trimester. The drug has been shown to be embryotoxic and to increase gross and skeletal fetal malformations.1 Although systemic exposure following IV administration is expected to be much greater than that with intravitreal therapy, there are no studies that examine such risks in pregnant women.

All our patients were inadvertently exposed to IVB within the first trimester. Literature on IVB use in pregnancy is sparse2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and before our publication its use in the first trimester was reported in only five women: three women had uneventful pregnancies and delivered healthy babies,2, 3, 4 whereas two women had spontaneous miscarriages following IVB.6 Reports of use in the second3, 5 and third trimesters3 have not been associated with adverse effects. The use of intravitreal ranibizumab during the third trimester has also been reported without complication.7

There is emerging evidence that IVB may cause systemic effects. Measurable serum levels of VEGF are observed in AMD patients after IVB8 and a reduction in DMO has been observed in contralateral eyes of DMO patients treated with bevacizumab.9 Systemic IgG crosses the placenta but it is not known whether bevacizumab or ranibizumab does the same. Bevacizumab is a full-length antibody incorporating an Fc region that may bind with IgG and cross the placenta.1, 3 Ranibizumab lacks the Fc portion and it is feasible that this reduces placental transfer.1, 3, 7 It is unclear which anti-VEGF would be the safest in pregnancy. Although ranibizumab may have reduced placental transfer, its smaller molecular size may give rise to higher maternal serum levels secondary to an increased ability to cross the blood–retinal barrier.3 Importantly, both drugs are contraindicated in pregnancy by the manufacturer and classed as ‘category C’ by the Federal Drugs Agency (www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/125085s267lbl.pdf). Avoidance of pregnancy post anti-VEGF therapy would need to reflect the half-life of ∼20 days (range 11–50)1 and precautions against pregnancy would need to be taken for at least 2 months.

The relationship between VEGF, hypertension, and maternal preeclampsia is poorly understood. Raised blood pressure following IVB has been reported10 and hypertension and preeclampsia may be related to circulating levels of VEGF,2, 4, 11, 12 which in turn could be affected by systemic anti-VEGF concentrations. In our only case of complicated pregnancy (Case 4), there was a significant past obstetric history. Cerebral haemorrhage and pulmonary artery stenosis may occur in complex pregnancy and it is not clear whether IVB administration during this patient’s pregnancy was contributory.

This case series provides further insights into IVB experience in early pregnancy and highlights the risk of inadvertent use. There is insufficient information to suggest that such use is safe, nor is there definitive evidence to suggest that it causes harm. We advise that ophthalmologists consider pregnancy when discussing anti-VEGF therapy in women of premenopausal age and advise avoiding pregnancy following such treatment.12 Furthermore, ophthalmologists need to be aware of an NHS alert on pregnancy testing before all surgeries.13 Care must be taken to ensure that the risks, benefits, and limited medical evidence of intravitreal anti-VEGF use during pregnancy are carefully discussed and documented. Should a woman become pregnant, close liaison with obstetric services is advised.

References

Genetech, Bevacizumab and Ranibizumab Prescribing Information: http://www.gene.com/download/pdf/avastin_prescribing.pdfhttp://www.gene.com/download/pdf/lucentis_prescribing.pdf. (accessed 27 November 2013).

Intrioni U, Casalino G, Cardani A, Scotti F, Finardi A, Candiani M et al. Intravitreal Bevacizumab for a subfoveal myopic choroidal neovascularization in the first trimester of pregnancy. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2012; 28 (5): 553–555.

Tarantola R, Folk J, Boldt H, Mahajan V . Intravitreal bevacizumab during pregnancy. Retina 30: 1405–1411 2010.

Wu Z, Huang J, Sadda S . Inadvertent use of Bevacizumab to treat choroidal neovascularization during pregnancy: a case report. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2010; 39: 143–145.

Rosen E, Rubowitz et Ferencz JR . Exposure to vertporfin and Bevacizumab therapy for choroidal neovascularization secondary to punctate inner choroidopathy during pregnancy. Eye 2009; 23: 1479.

Petrou P, Georgalas I, Giavaras G, Anastasiou E, Ntana Z, Petrou C . Early loss of pregnancy after intravitreal bevacizumab injection. Acta Ophthalmol 2010; 88 (4): e136.

Sarhianaki A, Katsimpris A, Petropoulos IK, Livieratou A, Theoulakis PE, Katsimpris JM . Intravitreal administration of ranibizumab for idiopathic choroidal neovascularization in a pregnant woman. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 2012; 229: 451–453.

Chakravarthy U, Harding SP, Rogers CA, Downes SM, Lotery AJ, Culliford LA et al. Alternative treatments to inhibit VEGF in age-related choroidal neovascularisation: 2-year findings of the IVAN randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013; 13: 61501–61509.

Bakbak B, Ozturk BT, Gonul S, Yilmaz M, Gedik S . Comparison of the effect of unilateral intravitreal bevacizumab and ranibizumab injection on diabetic macular edema of the fellow eye. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2013; 29 (8): 728–732.

Raiser R, Artunay O, Yuzbasioglu E, Senegal A, Behcecioglu H . The effect of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) administration on systemic hypertension. Eye 2009; 23: 1714–1718.

Sane DC, Anton L, Brosnihan KB . Angiogenic growth factors and hypertension. Angiogenesis 2004; 7: 193–201.

Errera MH, Kohly RP, da Cruz L . Pregnancy-associated retinal diseases and their management. Surv Ophthalmol 2013; 58 (2): 127–142.

National Patient Safety Agency. Rapid Response Report 11: Checking Pregnancy Before Surgery. National Patient Safety Agency: London, 2010. http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/alerts/?entryid45=73838.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

SPK has served as an advisor to Alimera Sciences, Bayer, and Novartis in the last 24 months and has received conference travel support and speaker fees from Novartis. Royal Bolton Hospital is involved with clinical research in ophthalmology sponsored by Allergan, Bayer, and Novartis within the last 24 months. MM declares that he has served as an advisor to Alimera Sciences, Bayer, and Novartis in the last 24 months and has received conference travel support from Novartis. Leeds Teaching Hospital Trust has been involved with clinical research in ophthalmology sponsored by Bayer, Novartis, and Quark within the last 24 months. CW has received conference support from Novartis and Allergan in the past.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sullivan, L., Kelly, S., Glenn, A. et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab injection in unrecognised early pregnancy. Eye 28, 492–494 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2013.311

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2013.311

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor medications during pregnancy: current perspective

International Ophthalmology (2021)

-

Bevacizumab

Reactions Weekly (2018)

-

Intravitreal vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor injection in unrecognised early pregnancy

Investigational New Drugs (2016)