Abstract

Aim

The aim of this study was to evaluate trends in visual impairment certification due to age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) in the Leeds metropolitan area between 2005 and 2010.

Methods

In this retrospective study, the primary causes of visual impairment certification in the Leeds metropolitan area between 2005 and 2010 were reviewed. ARMD was considered to be the cause of certification when recorded as the primary factor contributing to visual impairment in one or both eyes. The incidence of visual impairment certification due to ARMD was calculated using population estimates from the Office of National Statistics.

Results

ARMD was the primary cause of visual impairment certification in all study years, accounting for 58.7 and 50.8% of certifications in 2005 and 2010, respectively. For the same period, the incidence of certification due to ARMD fell from 364 to 248 per million population per year. This was largely the result of a fall in the incidence of visual impairment certification due to neovascular ARMD from 225 to 137 per million population per year, beginning in 2008 after the introduction of a local commissioning policy on the use of intra-vitreal ranibizumab.

Conclusion

The incidence of visual impairment certification due to ARMD in the Leeds metropolitan area appears to be falling. This is largely the result of a decrease in certification secondary to neovascular ARMD. This represents a change in the previously described trend for ARMD visual impairment certification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) is the major cause of sight impairment in older adults in the United Kingdom.1 It can be subclassified into atrophic ARMD (GA) and neovascular ARMD (NVARMD).2, 3 Although there is currently no effective treatment for GA, NVARMD can be treated with intra-vitreal ranibizumab (Lucentis, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Camberley, UK). Ranibizumab has been demonstrated to stabilise visual acuity in the majority of cases and was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2004 and licensed for use in Europe in 2006.4 Following a local commissioning policy, ranibizumab was available as a treatment for NVARMD in Leeds before the approval by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence in August 2008.

Previous studies have indicated a continuous increase in certifiable visual impairment secondary to ARMD, between 1933 and 1991, coincident with the increasing age of the population.5 In this study, we aimed to evaluate trends in the visual impairment certification due to ARMD in the Leeds metropolitan area between 2005 and 2010.

Methods

Sources of data

The primary cause of visual impairment certification was collected retrospectively in 2005 using the BD8 form. Following a change in UK practice, the same data was collected prospectively from Leeds Adult Social Care for the years 2008, 2009, and 2010 using the certificate of visual impairment (CVI) form. NVARMD was considered to be the cause of certification when recorded as the primary cause of visual impairment in one or both eyes.

Calculation of incidence

Population estimates for 2005, 2008, 2009, and 2010 were obtained from the Office of National Statistics. Incidence was defined as the number of new visual impairment certifications within a period of a year divided by the size of the population, and expressed per million population.

Results

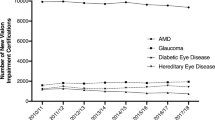

The total number of visual impairment certifications was found to be decreasing between the study years. There were 465 certifications in 2005, 446 in 2008, 410 in 2009 and 392 in 2010. Of these, there were 169 and 104 certifications due to NVARMD and GA in 2005, respectively, 100 and 139 certifications in 2008, 99 and 100 certifications in 2009 and 110 and 89 certifications in 2010. This was despite an increase in the total population for the Leeds metropolitan area from 750 600 in 2005 to 798 800 in 2010. ARMD was the leading cause of visual impairment certification in each study year, accounting for 58.7% of all certifications in 2005, 53.6% in 2008, 48.5% in 2009, and 50.8% in 2010. The incidence of visual impairment certification due to ARMD fell from 364 per million population per year in 2005 to 249 per million population per year in 2010. This was largely the result of a decrease in the incidence of NVARMD, from 225 per million population per year in 2005 to 138 in 2010 (Figure 1). The incidence of visual impairment certification secondary to GA did not show a similar trend.

Discussion

In this study, the incidence of visual impairment certification secondary to ARMD between 2005 and 2010 appears to be falling. This seems to be the result of a reduction in the number of certifications secondary to NVARMD, as the number of certifications secondary to GA remained more stable. This downward trend is in contrast to prior predictions5, 6 and was seen despite a 7% increase in the total population of the study area. This follows the local introduction of ranibizumab as a treatment for NVARMD in 2007 (Figure 1).

Since Sorsby first published an analysis of the number of blind people in England and Wales,7, 8 visual impairment certification has served as a mechanism for social care allocation. The original BD8 form was introduced by Department of Health in 1983 and was replaced by the CVI form in 2003.9, 10 The current criteria for visual impairment certification are summarised in Table 1. Certification is voluntary and the limitations of using visual impairment certification data to provide incident data have been noted before.11, 12, 13 Despite these limitations, certifications can be used as a marker of disease in a population and may also be used to evaluate the impact of a new intervention or treatment.

Between 2005 and 2010, the total number of certifications for the Leeds metropolitan area fell by 18%. Although this is a trend seen nationally, the number of certifications for GA and two of the other, common, local causes of visual impairment certification, namely glaucoma and retinal dystrophy, remained fairly constant.14 This suggests that at least some of the reduction in the total number of certifications may be the result of a reduction in the contribution of NVARMD. During the study period, the most significant innovation was the introduction of ranibizumab as a first-line treatment for NVARMD locally. Through a local commissioning policy this was introduced progressively between 2007 and 2008, in advance of NICE guidance. This study cannot determine whether the decrease in NVARMD certification is a direct consequence of this policy.

For some patients treated with ranibizumab, late visual loss is secondary to GA.15 One hypothesis was that a fall in the number of certifications due to NVARMD would be offset by a rise in certifications due to GA. This was not apparent between 2005 and 2010, although it may be a trend seen with longer term evaluation. It may have been masked by errors in recording the primary cause of visual impairment. The current CVI form permits the recording of multiple causes of visual impairment. An individual treated for NVARMD may experience progressive visual loss due to GA, and this could create confusion as to the primary cause of certification.

This study has a number of potential weaknesses. In addition to those already described, the use of certification data can only provide a minimum incidence of visual impairment due to ARMD. The strengths include the availability of data for a number of years and prospective data collection since 2007. For the population at risk, there is unlikely to have been significant movement into or from the Leeds metropolitan area. Although under-reporting remains a potential problem, there has not been a major change in the number of staff available to complete the CVI forms during the study period. For these reasons, it is likely that the comparison of incidence across the study period is valid. It would be interesting to see whether there are similar trends reported in other units or nationally.

Conclusion

The incidence of visual impairment certification due to ARMD in the Leeds metropolitan area fell between 2005 and 2010. This was largely the result of a decrease in visual impairment certification secondary to NVARMD, following the European licence for ranibizumab and the introduction of a local commissioning policy. This represents a change in the previously described trend for ARMD certification. Further studies are needed to establish the development of the trend with time and the relevance to a larger population area.

References

Owen CG, Fletcher AE, Donoghue M, Rudnicka AR. How big is the burden of visual loss caused by age related macular degeneration in the United Kingdom? Br J Ophthalmol 2003; 87: 312–317.

Kanski JJ, Bowling B . Age-related macular degeneration. In JJ Kanski, B Bowling (eds) Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach 7th ed Saunders: London, 2011, 611–616.

Bird AC, Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Chisholm IH, Coscas G, Davis MD et al. An international classification and grading system for age-related maculopathy and age-related macular degeneration. The International ARM Epidemiological Study Group. Surv Ophthalmol 1995; 39 (5): 367–374.

Mitchell P, Korobelnik JF, Lanzetta P, Holz FG, Prunte C, Schmidt-Erfurth U et al. Ranibizumab (Lucentis) in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: evidence from clinical trials. Br J Ophthalmol 2010; 94: 2–13.

Evans J, Wormald R . Is the incidence of registrable age-related macular degeneration increasing? Br J Ophthalmol 1996; 80: 9–14.

Bunce C, Wormald R . Leading causes of certification for blindness and partial sight in England & Wales. BMC Public Health 2006; 6: 58.

Sorsby A . The incidence and causes of blindness in England and Wales 1948–1962. Reports on Public Health and Medical Subjects, No. 114. HMSO: London, 1966.

Sorsby A . The Incidence and causes of blindness in England and Wales 1963–1968. Reports on Public Health and Medical Subjects, No. 128. HMSO: London, 1972.

Department of Health Form CVI: explanatory notes for consultants ophthalmologists and hospital eye clinic staff. Guidance 2003 Available from http://www.dh.gov.uk.

Department of Health Coordinating Services for Visually Handicapped People: Report to the Minister for the Disabled. HMSO: London, 1989.

Cormack TG, Grant B, Macdonald MJ, Steel J, Campbell IW . Incidence of blindness due to diabetic eye disease in Fife 1990-9. Br J Ophthalmol 2001; 85 (3): 354–356.

Bunce C, Xing W, Wormald R . Causes of blind and partial sight certifications in England and Wales: April 2007-March 2008. Eye 2010; 24 (11): 1692–1699.

Robinson R, Deutsch J, Jones HS, Youngson-Reilly S, Hamlin DM, Dhurjon L et al. Unrecognised and unregistered visual impairment. Br J Ophthalmol 1994; 78: 736–740.

Rostron E, McKibbin M . Trends in the incidence of visual impairment certification due to ARMD. Poster presentation. Annual Congress of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists 2011.

Rosenfeld PJ, Shapiro H, Tuomi L, Webster M, Elledge J, Blodi B . MARINA and ANCHOR Study Groups Characteristics of patients losing vision after 2 years of monthly dosing in the phase III ranibizumab clinical trials. Ophthalmology 2011; 118 (3): 523–530.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the help of the staff at Leeds Adult Social Care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Additional information

Presented as a poster at the Royal College of Ophthalmologists Annual Congress, Birmingham, 2011.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rostron, E., McKibbin, M. Visual impairment certification secondary to ARMD in Leeds, 2005–2010: is the incidence falling?. Eye 26, 933–936 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2012.61

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2012.61

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor in neovascular age-related macular degeneration – a systematic review of the impact of anti-VEGF on patient outcomes and healthcare systems

BMC Ophthalmology (2020)

-

Action on neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD): recommendations for management and service provision in the UK hospital eye service

Eye (2019)

-

Prevalence and incidence of blindness and other degrees of sight impairment in patients treated for neovascular age-related macular degeneration in a well-defined region of the United Kingdom

Eye (2015)

-

Defining response to anti-VEGF therapies in neovascular AMD

Eye (2015)

-

How many people in England and Wales are registered partially sighted or blind because of age-related macular degeneration?

Eye (2014)