Abstract

Purpose

To establish the impact of educational support on patients’ knowledge of glaucoma and adherence, in preparation for an intervention study.

Methods

Structured observation encapsulated the educational support provided during clinical consultations and patient interviews captured the depth of glaucoma knowledge, problems associated with glaucoma therapy, and adherence issues.

Results

One hundred and thirty-eight patients completed the study. Education was didactic in nature, limited for many patients and inconsistent across clinics. Patients showed generally poor knowledge of glaucoma with a median score of 6 (range 0–16). A significant association was found between educational support and knowledge for newly prescribed patients (Kendall's tau=0.30, P=0.003), but no association was found for follow-up patients (Kendall's tau=0.11, P=0.174). Only five (6%) patients admitted to a doctor that they did not adhere to their drop regimen, yet 75 (94%) reported at interview that they missed drops.

Conclusions

Although important, knowledge alone may not sufficiently improve adherence: a patient-centred approach based on ongoing support according to need may provide a more effective solution for this patient group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Poor adherence to therapy (the extent to which patients do not take medications as prescribed1) is prevalent in chronic, asymptomatic diseases such as glaucoma. A lack of glaucoma knowledge is frequently cited as a major cause of poor adherence to ocular hypotensive therapy.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Inconsistencies have been found in the assessment of knowledge; questionnaires range from a small number of general questions to detailed questions about diagnostic procedures,8 which can cause difficulties in identifying specifics gaps in knowledge that potentially affect adherence.

A recent Cochrane Review9 found only two randomised controlled trials, which attempted to improve knowledge; unfortunately, both studies were of short duration with brief interventions, and owing to missing data, methodological quality could not be assessed accurately.10, 11 Without the availability of good quality interventions, governing bodies have difficulties formulating evidence-based adherence guidelines. This is possibly why the recently launched Glaucoma Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) only touch on the issues of improving knowledge and promoting adherence.12 More conclusive evidence is warranted to allow recommendations to be forthcoming.

Glaucoma appears to have similar issues with adherence as other chronic conditions. It is yet to feature, however, in studies or reviews relating to poor adherence and chronic disease. A World Health Organisation project, which looked at improving rates of adherence to therapies, included nine conditions.13 A Cochrane review critically appraised the literature for adherence interventions and found 33 studies.14 An NHS-led scoping exercise extensively evaluated adherence studies for long-term conditions,15 and a number of studies have investigated poor adherence across chronic diseases.16, 17, 18 None of the above, however, included glaucoma; this may in part be owing to the poor quality of glaucoma adherence intervention studies, but may also suggest that glaucoma is seen as less of a priority than other chronic conditions. Collaboration with other areas of health care may provide the opportunity for glaucoma to be incorporated into large, sufficiently powered studies or meta-analyses of high methodological quality to allow generalisability of findings.

Previous studies have examined patients’ knowledge of glaucoma and adherence levels.3, 5, 6, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 One ophthalmic study objectively monitored doctor–patient interactions,24 yet the authors are unaware of any studies that have objectively observed clinical consultations to compare the nature and depth of educational support provided with patients’ knowledge of glaucoma and adherence to therapy. The aims of this survey were to investigate educational support, patients’ knowledge, and self-reported adherence via observation and interview, to generate hypotheses about the impact of educational support on patients’ knowledge of glaucoma and adherence, in preparation for an intervention study.

Materials and methods

Over a 4-month period, consecutive patients with a diagnosis of glaucoma suspect, ocular hypertension or open-angle glaucoma attending outpatient clinics at the Manchester Royal Eye Hospital were invited to participate. Written signed consent was obtained from all patients at recruitment. Patients incapable of making an informed choice about being involved in the study were excluded. Recruited patients were classified into one of two groups—newly prescribed or follow-up. Newly prescribed patients were recruited before being prescribed therapy and all subsequent clinical consultations were observed until therapy was commenced. This allowed the researcher to be present on the day of the first prescription to observe exactly what information was given and the depth of training and support provided, to assist the patient to instil eye drops and take ownership of their therapy. Their involvement ceased on the day therapy was prescribed following an interview. The observation period for the follow-up patients (already prescribed therapy) took place over one clinic appointment and was completed with an interview. The recruitment process and data collection methods are presented in Figure 1.

Data were collected via observation and interview. Two structured observation schedules (one for newly prescribed and the other for follow-up patients) were designed for observing doctors, optometrists, or nurses during clinical consultations with patients. The schedules were developed following a literature review,25, 26 a 2-month pilot period involving 150 h observing clinical consultations and discussions with experts in observational research and ophthalmology. The final drafts were ratified by a steering group of glaucoma specialists and academics. The time spent observing consultations was crucial for diminishing the ‘Hawthorne effect’,27, 28 allowing health-care professionals being observed to become more familiar with the researcher's presence and less conscious of the observation process. The observation schedules were checklists of statements concerning glaucoma and its management. During observation, statements were ticked off according to whether the information was given or the action occurred. The ‘newly prescribed patient’ schedule contained nine headings: investigations, diagnosis, prognosis, risk factors, medication, future management, adherence, eye drop instillation training, and additional support. The ‘follow-up patient’ schedule was less detailed containing six headings: investigations, medication, future management, adherence, eye drop advice and training (for prescription changes), and additional support. This structured design diminished the need for copious notes and allowed the researcher to concentrate on what was being said during clinical consultations. Total scores were calculated from the ticks given, for each fact about glaucoma or action taken, and a score was calculated for each patient for educational support provided. As the observation schedules differed for newly prescribed and follow-up patients, we could not make between-group comparisons in terms of the quality or quantity of educational support provided.

A 42-item questionnaire collected self-report data during the patient interviews. The questionnaire was developed following a literature review,29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 and discussions with experts in questionnaire development and ophthalmology. Content and face validity were confirmed by the steering group and a pilot involving 50 patients. Wording changes were made to improve patients’ understanding of some questions. Questions sought information relating to social status, knowledge of glaucoma, difficulties, or potential difficulties managing eye drops owing to other medical conditions or lifestyle, the support patients received for instilling drops, and adherence status. Adherence status involved follow-up patients only, as newly prescribed patients commenced therapy on the day of interview. Each question was allocated a number of pre-determined responses, which included an ‘other’ option. Non-pre-determined responses were coded post-interview, before quantitative analysis. Adherence was measured by asking patients to state on average how many drops they missed per month. Patients were also asked whether they stopped taking drops for any period of time and the reason(s) for this. Eleven questions tested knowledge of glaucoma. These were scored with a total maximum score of 17. The scoring system (Table 1) was devised during the pilot period and ratified by the steering group. Development of a score allowed between group comparison for knowledge and to look for associations between knowledge and factors such as educational support and adherence.

The study protocol was approved by the Central Manchester Research Ethics Committee. We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during this research.

Data analysis

Means and standard deviations were estimated when distributions were normal and medians and range when skewed. Differences between groups were analysed by the Mann–Whitney U, Kruskal–Wallis, and the Jonckheere–Terpstra tests. Associations were analysed by Kendall’s tau correlation coefficient. Tests were two tailed with α=0.05. Analysis was conducted with SPSS 15.0 for Windows.

Results

Within the time period, 182 eligible patients were approached, and 174 (96%) agreed to participate. All eight declining patients cited lack of time for an interview as the reason. Observation data were collected for 174 patients. Thirty-six new patients, however, did not proceed to interview as they did not commence treatment during the study. The analyses, therefore, include observation and interview data for 138 participants (58 newly prescribed and 80 follow-up patients).

Patient characteristics

Baseline demographic characteristics for newly prescribed and follow-up patients were similar for age, gender, and ethnicity; more details are provided in the patient demographic characteristics table (Table 2).

Consultation time

Of the 58 newly prescribed patients, only 13 were seen by an optometrist. The mean consultation time was 22.9 min (SD 3.3) for optometrists and 15.8 min (SD 4.1) for doctors. Follow-up patients were seen by medical staff, with a mean consultation time of 12.7 min (SD 4.8).

Observation data

For newly prescribed patients, the depth of information given varied across clinics and individual clinicians. The median educational support score for newly prescribed patients was 12 (range 4–18). A sample of the information given is presented in Table 3. Patients seen by an optometrist tended to be given more information. Some facts were implicit to the assessment, but not clearly stated to the patients. For example, the majority of patients were asked whether any family members had been diagnosed with glaucoma, yet only two were advised that glaucoma has a hereditary component and that immediate family members over the age of 40 years should have regular eye examinations.

Ten out of the 13 newly prescribed patients seen by an optometrist were given a brief demonstration of eye drop instillation and nine were given a leaflet explaining the technique. In the medical clinics, the technique was not shown. None of the patients involved in the study were observed instilling drops or referred to a nurse for instruction. Only one patient was asked whether he anticipated problems instilling drops.

The median educational support score for follow-up patients was 5 (range 0–13). There were no standard questions to ascertain whether patients were adhering to their drop regimen. The majority were asked only one question, ‘Are you managing your drops?’ The questioning usually stopped at this level as patients replied that they were. Only eight patients were asked more direct questions and only two patients were asked specifically whether they omitted drops.

Questionnaire data

Knowledge of glaucoma

Follow-up patients scored significantly higher than newly diagnosed patients (Mann–Whitney Z=−3.59, P<0.001), but the median knowledge score for both groups was low (newly prescribed 4 (range 0–13); follow-up 7 (range 0–16)). Thirty-three of the newly prescribed (57%) and 37 (46%) of the follow-up patients could not correctly state any facts about glaucoma. One newly prescribed patient thought it was a type of cancer. Thirty-four (59%) of the newly prescribed and 49 (61%) of the follow-up patients did not know which part of the eye becomes damaged in glaucoma. When asked what the drops did, 37 (64%) of the newly prescribed and 48 (60%) of the follow-up patients did not know, and one newly prescribed and three follow-up patients thought that drops would help to improve their vision. Forty-one (71%) of the newly prescribed patients were not aware that they should collect a new prescription every 28 days. Seventy patients (51%) did not know that the drops would be prescribed for life, and six thought that they would be discontinued as their condition improved.

The median knowledge score across the sample was 6 (range 0–16). It increased significantly with the level of highest qualification (Kendall's tau=0.29, P<0.001; Kruskal–Wallis χ2=16.44, df=2, P<0.001; standardised Jonckheere–Terpstra statistic 4.06, P<0.001). The score also significantly decreased with age (Kendall's tau=−0.25, P<0.001). Patients with a known family history of glaucoma scored significantly higher than those without (Mann–Whitney Z=−2.80, P=0.005). No association was found between the knowledge score and duration of glaucoma for follow-up patients (Kendall's tau=0.01, P=0.967).

There was a significant association between the educational support and the knowledge score for newly prescribed patients (Kendall's tau=0.30, P=0.003), but not follow-up patients (Kendall's tau=0.11, P=0.174).

Co-morbidity and eye drop instillation

One hundred and one patients (73%) had another medical condition, and 48 (35%) had more than one other condition. Of the conditions that could potentially affect patients’ ability to instil drops, arthritis was the most prevalent. Twenty-three (29%) follow-up patients required help to instil drops due mainly to difficulties aiming or squeezing the bottle and 11 (19%) of the newly prescribed patients anticipated having difficulties instilling the drops. None of the patients either used a drop aid or knew of their existence.

Adherence

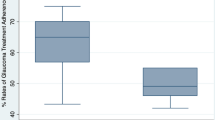

Only five (6%) follow-up patients admitted to a doctor that they omitted drops, yet 75 (94%) reported to the researcher that they missed drops. The median number of drops missed per month was 4, with a range of 0–40 (Figure 2). Forgetfulness was the most frequently reported reason for missing drops (41/75, 55%). Other reasons included difficulties aiming or squeezing the bottle, fear of using eye drops, carer unavailability, and prescription discrepancies. Fourteen patients reported stopping drops; periods ranged from 5 days to 2 months. Reasons included not taking them on holiday or during hospitalisation, forgetting to renew prescriptions, and allergic reaction.

There was no significant difference in the reported number of drops missed per month between male and female patients (Mann–Whitney Z=−0.48, P=0.635) or between patients with a known family history of glaucoma and those without (Mann–Whitney Z=−0.63, P=0.527). There was no significant association found between the number of drops missed per month and the glaucoma knowledge score (Kendall's tau=−0.05, P=0.595) or educational support (Kendall's tau=0.08, P=0.331). There was a weak but non-significant association between the number of drops missed per month and age (Kendall's tau=−0.14, P=0.095).

Discussion

This survey aimed to investigate the level of educational support required to help patients with ocular hypertension or glaucoma understand their condition and manage therapy effectively.

We found educational support to be limited for many patients and inconsistent across clinics; unsurprisingly, patients showed poor knowledge of glaucoma. Education was didactic in nature. Newly prescribed patients were not assessed on their ability to instil eye drops, given training or practice under supervision. None of the patients interviewed used a drop aid or knew of their existence, yet 29% of follow-up patients required help instilling drops and 19% of newly prescribed patients thought they may require help. Assessment of drop administration skills may assist in more accurately assessing patients’ ability to adhere to a drop regimen.20

We found that there was very little ongoing reinforcement with regard to adherence issues for follow-up patients. A Chinese study that compared knowledge between two cohorts found that patients who received ongoing support through membership of a glaucoma club were more knowledgeable about their disease than those who did not have this support.35 It is likely that the initial months of therapy are the most crucial in helping patients to understand their condition and take ownership of their eye drop care. Two qualitative studies found that barriers to adherence such as confusion over drop frequency, correct drop instillation, and the consequences of poor adherence were attributed to poor education within the months immediately following diagnosis.36, 37 In our study, newly prescribed patients who received more information achieved significantly higher knowledge scores than those who received less information. Although it would have been interesting to find out whether this correlated with better adherence, it was not within this study's remit. Future planned research will explore this important issue.

Only five patients admitted to a doctor that they regularly missed drops, yet 75 admitted this to the researcher. A number of patients sensed that doctors were busy and did not wish to delay them by discussing problems. Winfield et al38 found that 69% of patients did not report problems to their doctor even when asked. Friedman et al24 also found that patients did not like to admit to their physician that they missed drops, yet 48% of patients revealed adherence problems to the researcher. Providing patients with a relaxed environment may allow patients to discuss problems and be more truthful about poor adherence. Unfortunately, there is currently a lack of effective theories for motivating patients to adhere to therapy. Although methods such as motivational interviewing have been tried in other areas of health care,39, 40 and recently suggested for glaucoma patients,22 success is limited, and, therefore, until more work on developing theoretical models is carried out, evidence remains restricted.

Our study found reported adherence to be low compared with a number of studies,22, 23, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 which may be due to the following: the questionnaire was delivered by interview, which provided a 100% response rate, therefore reducing selection bias. Adherence was measured by asking patients on average how many drops they missed per month, had we narrowed the time period to how many drops they missed in the last month or last week, for example; a higher reported adherence rate may have ensued. The questionnaire purposely led participants through questions focusing on difficulties, the inconvenience of drop instillation, and co-morbidities; many patients had already admitted to missing drops before being asked about adherence. This non-threatening approach allowed more open responses by lessoning any imputation of deviance.48, 49

There are potentially a number of confounding factors to explain the no relation between adherence and other factors. First, this cross-sectional study attained a snapshot of the consultation process for follow-up patients, and more detailed information provided at previous clinic sessions would not have been captured; the educational support scores, therefore, did not encompass all the advice and support that follow-up patients may have received since diagnosis. Second, follow-up patients will have had many opportunities to talk to friends, family, and search on the internet for information about their condition. Their knowledge scores are unlikely to reflect only the educational support they received on the day of observation. Third, the narrow distribution of knowledge scores may also be a contributing factor to there being no apparent relation between adherence and knowledge.

We found a weak yet non-significant association between adherence and age. Other studies have found age and lifestyle to impact on adherence. Park et al50 found elderly patients to be more likely to adhere to therapy as their daily routines revolved around the day-to-day practicalities of coping with health problems. Younger patients appear to live more active lifestyles and spend periods of time away from home, or are involved in different activities leading them to forget medication when out of their normal routine. Studies involving patients with chronic diseases, such as diabetes51 and HIV,52 found that poor adherence arose as patients had difficulties changing their lifestyle to integrate a therapeutic regimen. As we also found, forgetfulness is frequently cited as a reason for poor adherence20, 37, 53, 54, 55; an intervention incorporating reminder systems into daily activities may prove advantageous.

This study was limited by its cross-sectional nature, but was a useful preliminary investigation of the advice and support currently provided and the needs of our glaucoma population. Owing to the time constraints for the recruitment period, participant numbers are small for some of the analyses and, therefore, care needs to be exercised when interpreting the results. Knowledge scores relied on patients remembering the information given and, therefore, were subject to recall bias. The knowledge score used in this study was developed in the absence of similar ratified tools; although crude, it allowed comparisons to be made. Nevertheless, this study has provided interesting information to fuel discussions with regard to the value of educational support for patients prescribed glaucoma therapy.

A shortage of clinical time, disparity of information about glaucoma, and the absence of structured care plans may have led to inconsistencies in the level of information and support provided. Improvements could be made by increasing clinical time and standardising verbal and written advice. However, improving education alone may not improve adherence levels; focusing on behavioural aspects may provide a more effective solution.19 A patient-centred approach following an assessment of needs, health beliefs, and lifestyle may be the key to improving adherence and providing a lasting intervention effect. Further research is needed to enable eye care services to provide the most effective care for improving adherence levels for this patient group.

References

Horne R . Adherence to medication: a review of the existing literature. In: Myers L, Midence K (eds). Adherence to Treatment in Medical Conditions. Harwood Academic Press: Amsterdam, 1998.

Costa VP, Spaeth GL, Smith M, Uddoh C, Vasconcellos JP, Kara-Jose N . Patient education in glaucoma: what do patients know about glaucoma? Arq Bras Oftalmol 2006; 69 (6): 923–927.

Cross V, Shah P, Bativala R, Spurgeon P . Glaucoma awareness and perceptions of risk among African-Caribbeans in Birmingham, UK. Diver Health Soc Care 2005; 2 (2): 81–90 (30 ref.).

Danesh-Meyer HV, Deva NC, Slight C, Tan YW, Tarr K, Carroll SC et al. What do people with glaucoma know about their condition? A comparative cross-sectional incidence and prevalence survey. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2008; 36 (1): 13–18.

Deokule S, Sadiq S, Shah S . Chronic open angle glaucoma: patient awareness of the nature of the disease, topical medication, compliance and the prevalence of systemic symptoms. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2004; 24 (1): 9–15.

Herndon LW, Brunner TM, Rollins JN . The glaucoma research foundation patient survey: patient understanding of glaucoma and its treatment. Am J Ophthalmol 2006; 141 (Suppl 1): S22–S27.

Hoevenaars JG, Schouten JS, van den Borne B, Beckers HJ, Webers CA . Socioeconomic differences in glaucoma patients’ knowledge, need for information and expectations of treatments. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2006; 84 (1): 84–91.

Olthoff CM, Schouten JS, van de Borne BW, Webers CA . Noncompliance with ocular hypotensive treatment in patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension an evidence-based review. Ophthalmology 2005; 112 (6): 953–961.

Gray T, Orton LC, Henson D, Harper R, Waterman H . Interventions for improving adherence to ocular hypotensive therapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 15 (2): Art. No. CD006132.

Sheppard J, Warner J, Kelley K . An evaluation of the effectiveness of a nurse-led glaucoma monitoring clinic. Int J Ophthalmic Nurs 2003; 7 (2): 15–21 (38 refs.).

Norell SE . Improving medication compliance: a randomised clinical trial. BMJ 1979; 2 (6197): 1031–1033.

NICE. Glaucoma: Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Open Angle Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension. National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: London, UK, 2009.

WHO. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Actionc World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X . Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008 (2): CD000011.

Horne R, Weinman J, Barber N, Elliot RA, Morgan M . Concordance, Adherence and Compliance in Medicine Taking: A conceptual Map and Research Priorities. National Institute for Health Research (NHIR) Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) Programme: London. http://www.sdo.nihr.ac.uk/sdo762004.html, 2005.

Barber N, Parsons J, Clifford S, Darracott R, Horne R . Patients’ problems with new medication for chronic conditions. Qual Saf Health Care 2004; 13 (3): 172–175.

Jackson JE, Doescher MP, Saver BG, Fishman P . Prescription drug coverage, health, and medication acquisition among seniors with one or more chronic conditions. Med Care 2004; 42 (11): 1056–1065.

Shrank WH, Hoang T, Ettner SL, Glassman PA, Nair K, DeLapp D et al. The implications of choice: prescribing generic or preferred pharmaceuticals improves medication adherence for chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166 (3): 332–337.

Hoevenaars JG, Schouten JS, van den Borne B, Beckers HJ, Webers CA . Will improvement of knowledge lead to improvement of compliance with glaucoma medication? Acta Ophthalmol 2008; 86 (8): 849–855.

Olthoff CM, Hoevenaars JG, van den Borne BW, Webers CA, Schouten JS . Prevalence and determinants of non-adherence to topical hypotensive treatment in Dutch glaucoma patients. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2009; 247 (2): 235–243.

Sakai H, Shinjyo S, Nakamura Y, Ishikawa S, Sawaguchi S . Comparison of latanoprost monotherapy and combined therapy of 0.5% timolol and 1% dorzolamide in chronic primary angle-closure glaucoma (CACG) in Japanese patients. J Ocular Pharmacol Therap 2005; 21 (6): 483–489.

Schwartz GF, Plake KS, Mychaskiw MA . An assessment of readiness for behaviour change in patients prescribed ocular hypotensive therapy. Eye 2009; 23 (8): 1668–1674.

Sleath B, Ballinger R, Covert D, Robin AL, Byrd JE, Tudor G . Self-reported prevalence and factors associated with nonadherence with glaucoma medications in veteran outpatients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2009; 7 (2): 67–73.

Friedman DS, Hahn SR, Quigley HA, Kotak S, Kim E, Onofrey M et al. Doctorpatient communication in glaucoma care: analysis of videotaped encounters in community-based office practice. Ophthalmology 2009; 116 (12): 2277–2285, e13.

Kogan JR, Holmboe ES, Hauer KE . Tools for direct observation and assessment of clinical skills of medical trainees: a systematic review. JAMA 2009; 302 (12): 1316–1326.

Westbrook JI, Ampt A . Design, application and testing of the Work Observation Method by Activity Timing (WOMBAT) to measure clinicians’ patterns of work and communication. Int J Med Inform 2009; 78 (Suppl 1): S25–S33.

Leonard K, Masatu MC . Outpatient process quality evaluation and the Hawthorne Effect. Soc Sci Med 2006; 63 (9): 2330–2340.

Sarantakos S . Social Research, 2nd edn. MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 1998.

Gasch AT, Wang P, Pasquale LR . Determinants of glaucoma awareness in a general eye clinic. Ophthalmology 2000; 107 (2): 303–308.

Hennell SL, Brownsell C, Dawson JK . Development, validation and use of a patient knowledge questionnaire (PKQ) for patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004; 43 (4): 467–471.

Kim S, Stewart JF, Emond MJ, Reynolds AC, Leen MM, Mills RP . The effect of a brief education program on glaucoma patients. J Glaucoma 1997; 6 (3): 146–151.

Landers JA, Goldberg I, Graham SL . Factors affecting awareness and knowledge of glaucoma among patients presenting to an urban emergency department. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2002; 30 (2): 104–109.

Lau JT, Lee V, Fan D, Lau M, Michon J . Knowledge about cataract, glaucoma, and age related macular degeneration in the Hong Kong Chinese population. Br J Ophthalmol 2002; 86 (10): 1080–1084.

Swift JA, Glazebrook C, Macdonald I . Validation of a brief, reliable scale to measure knowledge about the health risks associated with obesity. Int J Obes (London) 2006; 30 (4): 661–668.

Chen X, Chen Y, Sun X . Notable role of glaucoma club on patients’ knowledge of glaucoma. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2009; 37 (6): 590–594.

Lacey J, Cate H, Broadway DC . Barriers to adherence with glaucoma medications: a qualitative research study. Eye 2009; 23 (4): 924–932.

Taylor SA, Galbraith SM, Mills RP . Causes of non-compliance with drug regimens in glaucoma patients: a qualitative study. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2002; 18 (5): 401–409.

Winfield AJ, Jessiman D, Williams A, Esakowitz L . A study of the causes of non-compliance by patients prescribed eyedrops. Br J Ophthalmol 1990; 74 (8): 477–480.

Britt E, Hudson SM, Blampied NM . Motivational interviewing in health settings: a review. Patient Educ Counsel 2004; 53 (2): 147–155.

Kemp R, Kirov G, Everitt B, Hayward P, David A . Randomised controlled trial of compliance therapy. 18-month follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 172: 413–419.

Sleath B, Robin AL, Covert D, Byrd JE, Tudor G, Svarstad B . Patient-reported behavior and problems in using glaucoma medications. Ophthalmology 2006; 113 (3): 431–436.

Bloch S, Rosenthal AR, Friedman L, Caldarolla P . Patient compliance in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 1977; 61 (8): 531–534.

Bour T, Blanchard F, Segal A . Primary open-angle glaucoma: compliance with treatment and repercussion of glaucoma on the patient's life. Concerning 341 cases in the department of Marne, France [French]. J Franc Ophtalmol 1993; 16 (67): 380–391.

Gurwitz JH, Glynn RJ, Monane M, Everitt DE, Gilden D, Smith N et al. Treatment for glaucoma—adherence by the elderly. Am J Public Health 1993; 83 (5): 711–716.

Kass MA, Meltzer DW, Gordon M, Cooper D, Goldberg J . Compliance with topical pilocarpine treatment. Am J Ophthalmol 1986; 101 (5): 515–523.

MacKean JM, Elkington AR . Compliance with treatment of patients with chronic open-angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 1983; 67 (1): 46–49.

Rocheblave A . Cooperation of patients with chronic primary open-angle glaucoma. J Franc Opthalmol 1983; 6 (10): 837–841.

Foddy W . Constructing Questions for Interviews and Questionnaires: Theory and Practice in Social Research. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1993.

Hahn SR . Patient-centered communication to assess and enhance patient adherence to glaucoma medication. Ophthalmology 2009; 116 (11, Suppl): S37–S42.

Park DC, Hertzog C, Leventhal H, Morrell RW, Leventhal E, Birchmore D et al. Medication adherence in rheumatoid arthritis patients: older is wiser. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47 (2): 172–183.

Nagelkerk J, Reick K, Meengs L . Perceived barriers and effective strategies to diabetes self-management. J Adv Nurs 2006; 54 (2): 151–158.

Reynolds NR, Testa MA, Marc LG, Chesney MA, Neidig JL, Smith SR et al. Factors influencing medication adherence beliefs and self-efficacy in persons naive to antiretroviral therapy: a multicenter, cross-sectional study. AIDS Behav 2004; 8 (2): 141–150.

Konstas AG, Maskaleris G, Gratsonidis S, Sardelli C . Compliance and viewpoint of glaucoma patients in Greece. Eye 2000; 14 (Part 5): 752–756.

Patel SC, Spaeth GL . Compliance in patients prescribed eyedrops for glaucoma. Ophthal Surg 1995; 26 (3): 233–236.

Tsai JC, McClure CA, Ramos SE, Schlundt DG, Pichert JW . Compliance barriers in glaucoma: a systematic classification. J Glaucoma 2003; 12 (5): 393–398.

Acknowledgements

The project was jointly funded by the University of Manchester and Pfizer Limited UK and supported by the Manchester Academic Health Sciences Centre (MAHSC) and the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The study was funded by Pfizer Limited UK. This funding provided research support, which included computer equipment, and part funding of the researcher, Trish Gray's salary. Pfizer had no role in the design or conduct of this study. Dr Robert Harper and Ms Anne Fiona Spencer have been paid by Pfizer Limited UK as lecturers and workshop facilitators at educational events. Ms Cecilia Fenerty, Ms Agnes Lee, Dr Malcolm Campbell, Professor David Henson, and Professor Heather Waterman declare no potential conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gray, T., Fenerty, C., Harper, R. et al. Preliminary survey of educational support for patients prescribed ocular hypotensive therapy. Eye 24, 1777–1786 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2010.121

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2010.121

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Group-based patient education delivered by nurses to meet a clinical standard for glaucoma information provision: the G-TRAIN feasibility study

Pilot and Feasibility Studies (2018)

-

The Health Of Patients’ Eyes (HOPE) Glaucoma study. The effectiveness of a ‘glaucoma personal record’ for newly diagnosed glaucoma patients: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial

Trials (2015)

-

Improving adherence to glaucoma medication: a randomised controlled trial of a patient-centred intervention (The Norwich Adherence Glaucoma Study)

BMC Ophthalmology (2014)

-

Protocol for a randomised controlled trial to estimate the effects and costs of a patient centred educational intervention in glaucoma management

BMC Ophthalmology (2012)

-

Individualised patient care as an adjunct to standard care for promoting adherence to ocular hypotensive therapy: an exploratory randomised controlled trial

Eye (2012)