Abstract

Objectives

To compare responses in two patient populations with a questionnaire developed to identify those prescribed ocular hypotensive medication whose adherence may need improvement and who may be ready to change.

Methods

The content/face validity of a 62-item, self-administered questionnaire was confirmed by nine glaucoma specialists. Questions concerned demographics, health and medications, use of/problems with medications, and visual function. The questionnaire was administered anonymously to 102 consecutive patients in a glaucoma referral practice (‘glaucoma practice’) and 100 from a multispecialty ophthalmology practice (‘multispecialty practice’). All participants were prescribed ⩾1 ocular hypotensive medication and had no previous trabeculectomy.

Results

Patients in the glaucoma practice were more likely to be younger, African-American, and better educated (P<0.05 for each). In both, >80% had glaucoma with >60% diagnosed ⩾3 years previously. Most (glaucoma, multispecialty: 87, 93%) reported administering drops every day, but more in the multispecialty practice reported administering drops at the same time every day (79, 92%; P<0.05). Number of adherence problems (mean, 1/patient) and adherence scores (mean, 24; possible scale range, 0–25) were similar. Common adherence barriers were falling asleep and forgetting when the regular schedule changed or when travelling. In the glaucoma practice, the number of adherence problems was correlated with adherence score (r=–0.611; P<0.0001) and number of side effects (r=0.349; P<0.0001).

Conclusions

Similarities between patient populations limited our ability to compare responses between groups or to propose adherence counselling tailored to specific demographics. Until such recommendations are possible, physicians should incorporate adherence counselling broadly into their practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glaucoma and ocular hypertension are chronic and often asymptomatic conditions that require long-term adherence and persistence with ocular hypotensive medication regimens to reduce the risk of progression.1, 2 Unfortunately, both adherence and persistence have been found to be poor in patients with these conditions.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 The inability to distinguish between problems of efficacy and those of adherence and persistence may result in suboptimal patient outcomes and unnecessary and costly changes in therapy.

Assessing medication-taking behaviour, identifying patients in whom adherence (the extent to which patients’ behaviour correspond with providers’ recommendations11) or persistence (the extent to which the patients continue to administer medication over the long term12) may need to be improved, and evaluating readiness for behaviour change are key to improving patient medication-taking behaviour. Questioning patients directly about their medication-taking behaviour offers clinicians a window into patient behaviour independent of parameters such as intraocular pressure levels. We developed an instrument based on the transtheoretical model of change13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 to identify patients whose adherence may need to be improved and who may be susceptible to behaviour change. The objectives of this study were to develop an instrument to assess patient readiness for change and to test the instrument and compare responses in two patient populations.

Materials and methods

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Purdue University, and the study was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles maintained in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Verbal informed consent was obtained from patients before the study entry.

Data were collected using a 62-item, self-administered questionnaire based on the transtheoretical model of change, an integrative theoretical model of behaviour change that has been the basis for developing effective interventions to promote health behaviour change.13, 14, 15, 16, 17 It is a model of intentional change involving emotions, cognitions, and behaviours, and describes how people modify a problem behaviour or acquire a positive behaviour. The model makes no assumption about how ready individuals are to change and views change as a process involving progress through five stages (Figure 1).18 Before change in the target behaviour occurs, the time period is conceptualized as ‘behaviour intention’. After the behaviour has changed, the time period is conceptualized as ‘duration of behaviour’. Regression occurs when an individual reverts to an earlier stage; regression from action or maintenance to an earlier stage usually is termed ‘relapse.’

The temporal dimension of the stages of change.18

Questionnaire items were derived from a review of the ophthalmic and non-ophthalmic literature and modified to apply to patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. The survey was designed to be self-administered and included patient evaluations of health and medications, difficulties in taking ophthalmic medications,19 use of glaucoma medications, visual function,20, 21 adherence (Medication Adherence Report Scale22), and demographics). A draft of the questionnaire was reviewed for content and face validity by a panel of nine glaucoma specialists and behavioural and health economics experts (Appendix). The panel confirmed the content and face validities of the questionnaire. Changes to the survey were made reflecting the panel's recommendations to reduce forced choices by adding more coded responses for selected items and to amend wording to improve readability and response clarity.

Potentially eligible patients were from two practices in which one of the authors (GFS) served as a glaucoma specialist: (1) a tertiary metropolitan glaucoma referral practice (‘glaucoma practice’) and (2) a more rural multispecialty ophthalmology practice (‘multispecialty practice’). Consecutive patients diagnosed with primary open-angle glaucoma, primary closed-angle glaucoma, glaucoma suspect, or ocular hypertension who were prescribed at least one ocular hypotensive medication and who had no history of trabeculectomy were asked by GFS to participate. Prospective participants were advised that the clinician would not have access to information in individual questionnaires. Completed questionnaires were immediately sealed by the patient in a business reply envelope, and mailed to a coinvestigator (KSP) in a different state for analysis. Two patients in the multispecialty practice were unable to read the instrument, and their questionnaires were completed through interviews conducted in a private location (an examining room) by a technician. In all instances, interpretation of questions was left to the patient. Patients in the glaucoma practice who agreed to participate were given a $1 parking voucher. Descriptive statistics were performed, including frequencies, means, and SD (SPSS Version 10.1). χ2- and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for non-parametric comparisons of variables; t-tests and Pearson correlation were used for parametric comparisons.

Results

A total of 103 patients in the glaucoma practice were asked to participate and 102 completed a questionnaire. All 100 patients in the multispecialty practice who were asked to participate completed a questionnaire.

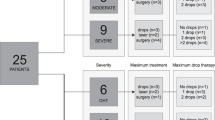

Compared to patients in the multispecialty practice, those in the glaucoma practice were younger and more likely to be African-American, to have higher incomes, and to be better educated (P<0.05 for each comparison; Table 1). In both groups, >80% had glaucoma and >60% were diagnosed at least three years previously; 45% of patients in the glaucoma practice and 57% of those in the multispecialty practice used a single type of eye drop (P=not significant; Table 2). More than 90% of patients in each practice had some type of insurance coverage for their eye drops. Mean numbers of reported comorbidities were 1.88±1.49 for patients in the glaucoma practice and 2.12±1.58 for those in the multispecialty practice; common comorbidities in both practices were hypertension, allergy, arthritis, and diabetes.

Use of glaucoma medications

Patients were given a list of thoughts and experiences that can affect the use of ocular hypotensive medications as directed, and were asked to indicate the frequency of occurrence of each within the past month by circling the numbers from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Patients in both practices generally were confident in their ability to take their medication(s) regularly without being reminded or encouraged by others (Table 3).

Adherence and the transtheoretical model of change

Patients answered the following five questions concerning eye drop adherence using the scale anchors of 1=always and 5=never (possible adherence score range=25): ‘I forget to take them’, ‘I alter or change on my own the dose,’ ‘I stop taking them for awhile,’ ‘I decide to miss a dose,’ and ‘I take less than instructed.’ Those in both practices reported high and very similar levels of adherence. The mean adherence score for those treated in the glaucoma practice was 23.98±1.29 (range, 20–25) and was 23.77±2.54 (range, 5–25) for those seen in the multispecialty practice.

Patient-reported adherence in both practices also was high when questions were asked in the context of the transtheoretical model of change (Table 4). Most patients in both practices reported administering eye drops every day, but significantly more patients in the multispecialty practice reported administering eye drops at the same time every day (92 vs 79% in the glaucoma practice; P<0.05). In all, 71–72% of patients in both practices reported that they expected to take ocular hypotensive medication(s) for the rest of their lives.

Side effects and problems with adherence

Patients were presented with a list of 12 possible glaucoma medication-related side effects, such as blurred vision, burning or stinging in eye(s), and redness, and were asked to check all that they experienced on a regular basis. Side effects did not appear to be a major problem for patients in either practice. Those in the glaucoma practice reported a mean of 0.84±1.26 side effects (range, 0–6), whereas those in the multispecialty practice reported a mean of 0.86±1.19 side effects (range, 0–6).

Patients were given a list of 23 ‘reasons for why you may not use your eye drops’ and were asked to check those that ‘explain why you miss a dose of your eye drops or do not use your eye drops.’ Representative reasons were ‘I just have difficulty remembering,’ ‘I fall asleep before it is time to use them,’ and ‘They have side effects that I do not like.’ In the glaucoma practice, patients reported a mean of 0.92±1.08 (range, 0–5) problems, similar to the mean of 1.07±2.52 (range, 0–23) problems reported by those seen in the multispecialty practice. In both the glaucoma and multispecialty practices, respectively, the most commonly reported barriers to adherence were falling asleep (20 and 16%), forgetting when the regular schedule changed (15 and 10%), and forgetting when travelling (14 and 20%). In the glaucoma practice, but not in the multispecialty practice, the number of adherence problems was significantly correlated with adherence score (r=−0.611; P<0.0001) and number of side effects (r=0.349; P<0.0001).

Discussion

The transtheoretical model of change has been the basis for developing instruments successfully used to assess and improve adherence in patients with a variety of medical conditions.23, 24, 25, 26, 27 To our knowledge, the current research is the first attempt to apply the model to a glaucoma population. Although the face and content validities of the questionnaire were confirmed by a panel of glaucoma experts, medication adherence by self-report was uniformly high among patients prescribed ocular hypotensive medications and making office visits to a glaucoma practice or to a multispecialty practice. Given this lack of variability, we were not able to identify those whose adherence needed to be improved and who were ready to change.

The very high patient-reported adherence rates likely reflect overreporting because of, at least in part, the general inclination of patients to report behaviours they believe their physicians expect28 as well as the tendency of patients to improve adherence around the time of the office visit (‘white-coat adherence’).29, 30 Kass et al31 found adherence rates reported by patient interview (97%) or medication log (99%) were substantially higher than the 76% rate measured by eye drop monitor. Cramer et al30 reported that patients were best at dosing 5 days before an office visit with a sharp decline in adherence a month later—from 88 to 67%.

In addition to the issue of overreporting adherence, characteristics of patients in the glaucoma and multispecialty practices may have further limited our ability to identify those who were below the maintenance level of adherence (‘usually taking glaucoma medications every day for more than 6 months’) and who were ready to change. First, we included only those who kept a follow-up appointment, although others32, 33 have found non-adherence with follow-up to be associated with poorer medication adherence. Second, visit non-adherence is significantly more likely to occur among glaucoma suspects than among those with definite glaucoma,33 but we could not stratify our analyses by diagnosis because more than 80% of participants in both practices were diagnosed with glaucoma. Third, patients prescribed an ocular hypotensive medication <6 months before administration of the questionnaire could not, by definition, report the maintenance behaviour; in our patient groups, only 16% of patients were diagnosed with the condition for which they were receiving ocular hypotensive therapy ⩽1 year previously, further limiting response variability. Fourth, patients who participated in the current research (as well as those included in the survey portion of the Glaucoma Adherence and Persistency Study (GAPS))34 may not be representative of the wider population of glaucoma patients as all consented to answer questions about their conditions and medication-taking behaviours. Given these limitations, testing of the instrument in larger, more diverse groups of patients seems warranted. Finally, excluding patients who have undergone trabeculectomy can skew the results in specific ways. It may be that the less adherent patients are more likely to progress and need trabeculectomy, so results are more skewed towards adherent patients. Alternatively, patients who have undergone trabeculectomy in one eye and are on medications in the fellow eye may become more adherent to an effort to reduce the chance of having to undergo additional surgery, or those taking drops following qualified success or failure of surgery may have increased motivation to adhere.

Our inability to identify patients whose adherence needed to be improved and who were ready for behaviour change suggests that motivational interviewing35, 36, 37 may be important in all physician–patient encounters. Motivational interviewing, also termed patient-centered counselling, is non-judgmental, empathetic, and encouraging, and is characterized by reflective listening, and positive feedback rather than by direct questioning, persuasion, and giving of advice. The effectiveness of motivational interviewing has been documented in programmes targeting diet and exercise,38, 39 smoking cessation,40, 41and medical adherence.42, 43

Although the utility of the current questionnaire and of motivational interviewing in patients prescribed ocular hypotensive therapy requires further testing, others19, 32, 34, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49 have found adherence in this patient population to be problematic and have identified several barriers that parallel the situational issues (eg, forgetting when travelling or when the regular schedule changed19) reported broadly by patients in both the glaucoma and multispecialty practices. Research is needed to further specify health-related beliefs, lapses in or dissatisfaction with doctor–patient communication, and situational obstacles that negatively impact adherence in this patient population. In particular, the impact of gender on readiness for behaviour change should be assessed, as male patients have been reported to be more likely to be non-adherent.3

In conclusion, similarities between patient populations limited our ability to compare responses between groups or to propose adherence counselling tailored to specific demographics. Until such recommendations are possible, physicians should incorporate adherence counselling broadly into their practices.

References

Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, Johnson CA, Keltner JL, Miller JP et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002; 120: 701–713.

Stewart WC, Chorak RP, Hunt HH, Sethuraman G . Factors associated with visual loss in patients with advanced glaucomatous changes in the optic nerve head. Am J Ophthalmol 1993; 116: 176–181.

Olthoff CM, Schouten JS, van de Borne BW, Webers CA . Noncompliance with ocular hypotensive treatment in patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension: an evidence-based review. Ophthalmology 2005; 112: 953–961.

Nordstrom BL, Friedman DS, Mozaffari E, Quigley HA, Walker AM . Persistence and adherence with topical glaucoma therapy. Am J Ophthalmol 2005; 140: 598–606.

Gurwitz JH, Glynn RJ, Monane M, Everitt DE, Gilden D, Smith N et al. Treatment for glaucoma: adherence by the elderly. Am J Public Health 1993; 83: 711–716.

Reardon G, Schwartz GF, Mozaffari E . Patient persistency with pharmacotherapy in the management of glaucoma. Eur J Ophthalmol 2003; 13 (Suppl 4): S44–S52.

Reardon G, Schwartz GF, Mozaffari E . Patient persistency with ocular prostaglandin therapy: a population-based, retrospective study. Clin Ther 2003; 25: 1172–1185.

Reardon G, Schwartz GF, Mozaffari E . Patient persistency with topical ocular hypotensive therapy in a managed care population. Am J Ophthalmol 2004; 137 (1 Suppl): S3–S12.

Schwartz GF . Compliance and persistency in glaucoma follow-up treatment. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2005; 16: 114–121.

Schwartz GF, Reardon G, Mozaffari E . Persistency with latanoprost or timolol in primary open-angle glaucoma suspects. Am J Ophthalmol 2004; 137 (1 Suppl): S13–S16.

Sackett DL . Introduction. In: Sackett DL, Haynes RB (eds). Compliance with Therapeutic Regimens. Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, 1976, pp 1–6.

Schwartz GF . Measuring persistency with drug therapy in glaucoma management. Am J Manag Care 2002; 8 (Suppl): S237–S239.

Janis IL, Mann L . Decision Making: A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice and Commitment. Free Press: New York, 1977.

Bandura A . Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 1977; 84: 191–215.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC . Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983; 51: 390–395.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC . In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol 1992; 47: 1102–1114.

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF . The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 1997; 12: 38–48.

Cancer Prevention Research Center. Transtheoretical model. Available at:: http://www.uri.edu/research/cprc/transtheoretical.htm. Accessed 8 January, 2008.

Tsai JC, McClure CA, Ramos SE, Schlundt PG, Pichert JW . Compliance barriers in glaucoma: a systematic classification. J Glaucoma 2003; 12: 393–398.

Mangione CM, Lee PP, Pitts J, Gutierrez P, Berry S, Hays RD . Psychometric properties of the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ). Arch Ophthalmol 1998; 116: 1496–1504.

Mangione CM, Lee PP, Gutierrez PR, Spritzer K, Berry S, Hays RD et al. Development of the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire. Arch Ophthalmol 2001; 119: 1050–1058.

Horne R . The Medication Adherence Report Scale. University of Brighton Press: Brighton, England, 2004.

Aloia MS, Arnedt JT, Stepnowsky C, Hecht J, Borrelli B . Predicting treatment adherence in obstructive sleep apnea using principles of behavior change. J Clin Sleep Med 2005; 1: 346–353.

Lawsin C, DuHamel K, Weiss A, Rakowski W, Jandorf L . Colorectal cancer screening among low-income African Americans in East Harlem: a theoretical approach to understanding barriers and promoters to screening. J Urban Health 2007; 84: 32–44.

Kavookjian J, Berger BA, Grimley DM, Villaume WA, Anderson HM, Barker KN . Patient decision making: strategies for diabetes diet adherence intervention. Res Social Adm Pharm 2005; 1: 389–407.

Johnson SS, Driskell MM, Johnson JL, Prochaska JM, Zwick W, Prochaska JO . Efficacy of a transtheoretical model-based expert system for antihypertensive adherence. Dis Manag 2006; 9: 291–301.

Johnson SS, Driskell MM, Johnson JL, Dyment SJ, Prochaska JO, Prochaska JM et al. Transtheoretical model intervention for adherence to lipid-lowering drugs. Dis Manag 2006; 9: 102–114.

Krousel-Wood M, Thomas S, Muntner P, Morisky D . Medication adherence: a key factor in achieving blood pressure control and good clinical outcomes in hypertensive patients. Curr Opin Cardiol 2004; 19: 357–362.

Feinstein AR . On white-coat effects and the electronic monitoring of compliance. Arch Intern Med 1990; 150: 1377–1378.

Cramer JA, Scheyer RD, Mattson RH . Compliance declines between clinic visits. Arch Intern Med 1990; 150: 1509–1510.

Kass MA, Gordon M, Meltzer DW . Can ophthalmologists correctly identify patients defaulting from pilocarpine therapy? Am J Ophthalmol 1986; 101: 524–530.

Friedman DS, Hahn SR, Gelb L, Tan J, Shah SN, Kim EE et al. Doctor-patient communication, health-related beliefs, and adherence in glaucoma: results from the Glaucoma Adherence and Persistency Study. Ophthalmology 2008; 115 (8): 1320–1327, 1327.e1-3.

Kosoko O, Quigley HA, Vitale S, Enger C, Kerrigan L, Tielsch JM . Risk factors for noncompliance with glaucoma follow-up visits in a residents’ eye clinic. Ophthalmology 1998; 104: 2105–2111.

Friedman DS, Quigley HA, Gelb L, Tan J, Margolis J, Shah SN et al. Using pharmacy claims data to study adherence to glaucoma medications: methodology and findings of the Glaucoma Adherence and Persistency Study (GAPS). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007; 48: 5052–5057.

Resnicow K, DiIorio C, Soet J et al. Motivational interviewing in medical and public health settings. In Miller W, Rollnick S (eds). Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change, 2nd ed. Guilford Press: New York, 2002, pp 251–269.

Resnicow K, DiIorio C, Soet JE, Ernst D, Borrelli B, Hecht J . Motivational interviewing in health promotion: It sounds like something is changing. Health Psychol 2002; 21: 444–451.

Britt E, Hudson SM, Blampied NM . Motivational interviewing in health settings: a review. Patient Ed Couns 2004; 53: 147–155.

Harland J, White M, Drinkwater C, Chinn D, Farr L, Howel D . The Newcastle exercise project: a randomised controlled trial of methods to promote physical activity in primary care. BMJ 1999; 319: 828–832.

Resnicow K, Wallace D, Jackson A, Digirolamo A, Odom E, Wang T et al. Dietary change through Black churches: baseline results and program description of the Eat for Life Trial. J Cancer Ed 2000; 15: 156–163.

Glasgow R, Whitlock E, Eakin E, Lichtstein E . A brief smoking cessation intervention for women in low-income Planned Parenthood clinics. Am J Public Health 2000; 90: 786–789.

Butler C, Rollnick S, Cohen D, Bachman M, Russell I, Stott N . Motivational consulting vs brief advice for smokers in general practice: A randomized trial. Br J Gen Pract 1999; 49: 611–616.

Kemp R, Hayward P, Applewhaite G, Everitt B, David A . Compliance therapy in psychotic patients. Randomized controlled trial. BMJ 1996; 312: 345–349.

Kemp R, Kirov B, Everitt B, Hayward P, David A . Randomised controlled trial of compliance therapy. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 172: 413–419.

Konstas AG, Maskaleris G, Gratsonidis S, Sardelli C . Compliance and viewpoint of glaucoma patients in Greece. Eye 2000; 14: 752–756.

MacKean JM, Elkington AR . Compliance with treatment of patients with chronic open-angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 1983; 67: 46–49.

Patel SC, Spaeth GL . Compliance in patients prescribed eye drops for glaucoma. Ophthalmic Surg 1995; 26: 233–236.

Taylor SA, Galbraith SM, Mills RP . Causes of non-compliance with drug regimens in glaucoma patients: a qualitative study. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2002; 18: 401–409.

Gelb L, Friedman DS, Quigley HA, Lyon DW, Tan J, Kim EE et al. Physician beliefs and behaviors related to glaucoma treatment adherence: the GAPS study. J Glaucoma 2008, (forthcoming).

Quigley HA, Friedman DS, Hahn SR . Evaluation of practice patterns for the care of open-angle glaucoma compared with claims data. The Glaucoma Adherence and Persistency Study. Ophthalmology 2007; 114: 1599–1606.

Acknowledgements

The editorial support, including contributing to the first draft of the manuscript, revising the paper based on author feedback, and styling the paper for journal submission was provided by Jane G Murphy, PhD, of Zola Associates and was funded by Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA. Drs Schwartz and Plake were paid consultants to Pfizer in connection with the development of this study. Dr Mychaskiw is an employee of Pfizer Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The results of this study were presented in part at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, from 27 April to 1 May 2008, in Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, and at the Quadriennial Meeting 2008 of the European Glaucoma Society, from 1 to 6 June 2008, in Berlin, Germany.

Appendix

Appendix

Members of the questionnaire review panel: Brian E Flowers, MD, Ophthalmology Associates, Fort Worth, TX, USA; Steven R Hahn, MD, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA; Steven M Kymes, PhD, Washington University in St Louis, St Louis, MO, USA; Paul P Lee, MD, USA, JD, Duke University Eye Center, Durham, NC, USA; Richard D Mills, MD, MPH, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; Richard K Parrish, MD, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Miami, FL, USA; Anthony Realini, MD, West Virginia University Eye Institute, Morgantown, WV, USA; James C Tsai, MD, MBA, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA; Thom Zimmerman, MD, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, USA.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schwartz, G., Plake, K. & Mychaskiw, M. An assessment of readiness for behaviour change in patients prescribed ocular hypotensive therapy. Eye 23, 1668–1674 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2008.337

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2008.337