Abstract

To unravel missing genetic causes underlying monogenic disorders with recurrence in sibling, we explored the hypothesis of parental germline mosaic mutations in familial forms of malformation of cortical development (MCD). Interestingly, four families with parental germline variants, out of 18, were identified by whole-exome sequencing (WES), including a variant in a new candidate gene, syntaxin 7. In view of this high frequency, revision of diagnostic strategies and reoccurrence risk should be considered not only for the recurrent forms, but also for the sporadic cases of MCD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Familial forms of Mendelian disorders with recurrences in sibling and healthy parents are usually predicted to result from two modes of inheritance: X-linked or autosomal recessive with homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations inherited from healthy heterozygous parents. Conventional Bayesian methods taking into account prior probability for each event and conditional probability on the basis of pedigree analysis are usually used to determine relative probabilities for each pattern of inheritance.1 For instance, in the EuroMRX consortium study focused on familial forms of intellectual disability (ID) with at least two affected brothers, authors suggested that 63% of the ID in these families should then be X-linked.2 This estimation contrasts with the much lower observed frequency of 17% shown in a cohort of potential X-linked ID families with two affected boys.2 For disorders with autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance, undiagnosed cases are common despite proper analysis of known and candidates related genes.

How can we explain these ‘missing genetic causes’?

One could argue that the missing mutations could be present in not-yet identified genes, or in non-coding regions of the genome. Alternative genetic explanations include autosomal dominant inheritance with reduced penetrance, polygenic or multifactorial inheritance modulated by the influence of non-genetic factors.

Here, we explored the hypothesis that these familial cases could be attributed to parental mosaic germline mutations. Such events have been already described for few well-defined disorders using targeted analysis of specific genes. The percentage of germline or somatic mutations has been found to be between 6 and 11.5%.3 However, to our knowledge this hypothesis was rarely explored in an unbiased manner for a heterogeneous group of disorders.4 In this study, we used whole-exome sequencing (WES) approach to assess the contribution of parental mosaic germline mutations in familial forms of malformations of cortical development (MCD).

Subjects and methods

We selected 18 families with at least two sibs affected and healthy parents. Index cases were affected by lissencephaly, polymicrogyria, heterotopia or microcephaly, with or without abnormalities of the corpus callosum, brainstem or cerebellum. Details about pedigrees, clinical and imaging phenotypes are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

We performed WES in trios made of one child with an MCD and his two unrelated parents, except one consanguineous family (P370), using standard protocols developed at CNG (Centre National de Génotypage) and pipeline analysis of Paris Descartes University bioinformatics platform.3 Exome sequencing quality data are available in Supplementary Table 2. We analyzed variants affecting coding regions and essential splicing sites and excluded all variants with a frequency greater than 1% according to genomic databases (dbSNP, 1000 Genomes, Exome variant server and local platform database). We used different genetics models of inheritance (de novo, recessive, X-linked) to perform familial analysis of trio’s exome data. Finally, relevant variants were confirmed by PCR and Sanger sequencing and tested for familial segregation using genomic DNA from the patient, his or her parents and sibs.

We used different methods to determine parental origin of de novo variants, depending on haplotypes, informativeness of SNP and distance between SNP and mutation (Supplementary Figure 3 and legend of Supplementary Figure 3).

In the suspected case of somatic variant, confirmation and estimation of the percentage of cells bearing the variant was performed by Droplet Digital PCR approach using DNA extracted from peripheral blood of P248 proband and his two parents (QX100 Droplet Digital PCR System, Bio-Rad Life Science Research, Hercules, CA, USA). We used both variant and wild-type specific primers associated to specific probes. Data were analyzed with QuantaSoft v.1.4 software (Bio-Rad Life Science Research).

Reference sequences used: DYNC1H1 (NM_001376.4), TUBA1A (NM_001270399.1), STX7 (NM_003569.2), ASNS (NM_133436.3), VPS13B (NM_017890.4), REELN (NM_005045.3), WDR62 (NM_173636.4), LACTB (NM_032857.3).

All variants have been submitted in ClinVar database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/); accession number for the new variant in STX7 gene: SCV000222759.

Results and Discussion

That strategy allowed us to identify five families with variants in genes involved in autosomal MCD disorders (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1) and four families with evidence for the presence of parental germline mosaicism (Table 1 and Figure 1). Although most variations involve known MCD-related genes, we also identified in a family (P248, Table 1 and Figure 1) with subcortical band heterotopia, paternal germline and somatic variant in a novel gene, STX7 (Syntaxin 7).

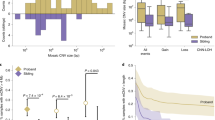

Families with parental germline mosaic variants. (a) P248-STX7 variant. (a1, a2, a3) Proband’s MRI sections showing the extended heterotopic band. (a4) WES reads showing the STX7 variant and one variant read in the father. (a5) Droplet digital PCR data confirming the somatic mosaicism in the father: variant allele is present in 213 out of 3882 positive droplets in first father well; 207 out of 3788 in second well; 239 out of 3738 in third well; absent in the mother and present in 1982 out of 2053 droplets in the proband. (a6) Father’s MRI showing the milder posterior band heterotopia (arrow). (b) P474-TUBA1A variant. (b1, b2, b3) Patient’s MRI sections showing the corpus callosum agenesis, brainstem and cerebellum abnormalities, bilateral opercular dysplasia and dysmorphic ventricular horns. (c) P374-DYNC1H1 mutation. (c1, c2) Histopathological sections showing heterotopic neuronal cells, extended polymicrogyria, enlarged germinative zones and disorganized axonal tracts (arrows). (d) P5-DYNC1H1 variant. Star symbol is to highlight position of heterozygous mutation in affected individuals.

In addition to the index case, a 3-year-old boy with posteriorly predominant subcortical band heterotopia, this family includes a female fetus for which pregnancy follow-up revealed a microcephaly with pachygyria that led to parental decision of medical termination of pregnancy. In this family the de novo c.159A>C, p.(Gln53His) heterozygous variant in STX7 gene revealed by WES in the index cases has been confirmed by Sanger sequencing in both siblings but not in the parents (Figure 1,Table 1). However, a close look to the reads generated by the high throughput sequencing showed the presence of this variant three times out of 95 father’s reads consistent with a somatic mosaicism. Droplet PCR analysis revealed variant alleles in 4.8% of paternal blood cells (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 7). A recent MRI performed in the father showed bilateral and symmetrical posterior band heterotopia (Figure 1).

As mentioned in Supplementary Table 3, another variant, c.46G>A, p.(Gly16Arg) in LACTB gene, has been also found in the offspring but not in the parents of this family. This variant is known and described in dbSNP (rs34925488) that is present in about 3% of the population.

We then focused on the variant in STX7, that encodes the 261 amino acids protein, called syntaxin 7, involved in vesicle trafficking5 and required for late endosome-lysosome fusion.6 Syntaxins are a family of transmembrane proteins that belong to the SNARE complex (Soluble N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor Attachment protein REceptor) known to be implicated in NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor and dopaminergic receptor function7. To further support our finding, we analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR STX7 expression using RNA extracted from different tissues and showed that STX7 transcripts are ubiquitous with a predominant level in the central nervous system (Supplementary Figure 2). Moreover, the p.(Gln53His) variant in STX7 gene was predicted by Polyphen 2 and mutation Tester to alter a highly conserved amino acid and to be damaging. Taken together, these data are consistent with STX7 variant as the likely cause of the disease phenotype in this family. We screened the complete coding sequences and splice sites of this gene in a cohort of 276 individuals affected by various MCDs, but did not identify any additional potential deleterious variant. Retrospectively, the rarity of the type of MCD observed in this family (posterior band heterotopia) might explain the absence of additional mutation in the screened cohort, mainly enriched with PMG and pachygyria cases.

The remaining parental germ line variants were identified in known MDC-related genes (Figure 1 and Table 1). Briefly, P5 family was included because of the occurrence of two cases with microlissencephaly and arthrogryposis that led to pregnancy terminations. In this family, we identified in both fetuses a common variant in DYNC1H1 gene (c.1738G>A, p.(Glu580Lys)) that was not detected in the parental DNA. We could highlight the maternal origin of the variant (Supplementary Figure 3). For P474 family, the c.1148C>T, p.(Ala383Val) variant in TUBA1A gene detected by WES was confirmed in both patients, the boy who died at the age of 13 months and in his young sister. They were both affected by a complex MCD combined with cerebellar hypoplasia and agenesis of the corpus callosum. Though we did not detect the variant in the parents blood DNA, it was possible to trace its maternal origin (Supplementary Figure 3).

Finally, the P374 family with three affected fetuses was referred to our laboratory for diagnostic purposes. We identified a heterozygous variant in DYNC1H1 gene in a female fetus after pregnancy termination for agenesis of the corpus callosum and ‘double cortex’ aspect. We confirmed the c.8159G>A, p.(Arg2720Lys) variant in the other female and male aborted fetuses who shared the same malformation. Interestingly, neuropathological analysis showed focal polymicrogyria with major neuronal migration defect (multiples bands and nodules of heterotopia) and abnormal axonal guidance with anarchical tracts in the white matter and the brainstem. In addition to agenesis of the corpus callosum, cerebellum was hypoplastic with heterotopias. It is the first description of DYNC1H1-related histological anomalies. This variation was not detectable in parental blood DNA and determination of parental origin was hampered by the lack of informative SNP nearby the variant (Supplementary Figure 3).

In total, out of 18 families with recurrent forms of MCD, variants were identified in 5 families with autosomal recessive inheritance and 4 families with parental germline mosaicism (9 out of 18; 50%). Retrospectively, it would have been possible to identify most variants by testing targeted MDC-related genes; however, as familial segregation and phenotypes were not always suggestive, the unbiased WES emerged as an appropriate strategy. For the remaining nine families, we did not find any variant shared by affected sibs in five families; and identified homozygous, compound heterozygous or X-linked variants in candidate genes in four families, highlighted in Supplementary Tables 3.

Importantly, our study revealed that parental germline mosaicism accounts for about 15% of recurrent forms of MCD and should lead to a revision of estimated risk for disease reoccurrence and genetic counseling for couples with an affected child who carries a variant considered as de novo. Also, one should consider mosaic germline mutation when investigating apparent autosomal recessive familial disorders. Finally, this unbiased WES approach should be applied to assess parental germline mosaicism contribution in other heterogeneous groups of genetic diseases.

References

Young ID, Nugent Z, Grimm T : Autosomal recessive or sex linked recessive: a counselling dilemma. J Med Genet 1986; 23: 32–34.

de Brouwer AP : Mutation frequencies of X-linked mental retardation genes in families from the EuroMRX consortium. Hum Mutat 2007; 28: 207–208.

Poirier K, Lebrun N, Broix L et al: Mutations in TUBG1, DYNC1H1, KIF5C and KIF2A cause malformations of cortical development and microcephaly. Nat Genet 2013; 45: 639–647.

Erickson RP : Somatic gene mutation and human disease other than cancer: an update. Mutat Res 2010; 705: 96–106.

Wang H, Frelin L, Pevsner J : Human syntaxin 7: a Pep12p/Vps6p homologue implicated in vesicle trafficking to lysosomes. Gene 1997; 199: 39–48.

Mullock BM, Smith CW, Ihrke G et al: Syntaxin 7 is localized to late endosome compartments, associates with Vamp 8, and Is required for late endosome-lysosome fusion. Mol Biol Cell 2000; 11: 3137–3153.

Pei L, Lee FJ, Moszczynska A, Vukusic B, Liu F : Regulation of dopamine D1 receptor function by physical interaction with the NMDA receptors. J Neurosci 2004; 24: 1149–1158.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families for their participation and medical doctors for their collaboration. We particularly thank Drs B. Gilbert, C. Vincent-Delorme, C. Quelin, M. Fradin, S. Mercier, C. Beneteau, F. Razavi, M. Ballesta-Martinez and H. Jilani. We also thank Peter de Witte, Duc Hung Pham and Camila Esguerra for their thoughtful comments. We thank all members of the Cochin Institute genomic platform with A. Vigier, the Centre National de Genotypage with C. Baulard and M. Delepine, members of the Cochin Hospital Cell Bank and Paris Descartes Bioinformatics platforms for their technical and bioinformatic assistance. This work was supported by funding from INSERM, the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (Equipe FRM; J.C–DEQ20130326477), the Fondation JED, the Fondation Maladies Rares, the Agence National de Recherche (ANR Blanc 1103 01, project R11039KK; ANR E-Rare-012-01, project E10107KP; ANR-13-BSV-0009-01) and the EU-FP7 projects GENECODYS (grant number 241995) and DESIRE (grant agreement 602531).

Author contributions

JC instigated and coordinated the study with KP. JLZ, KP and AE analyzed the WES data and performed the validation and segregation studies. AE performed all DNA extractions from the patient sample. JLZ, NL with JN performed and analyzed the STX7 screening, qPCR and Digital PCR. NL determined the parental origin of mutations. LB performed and analyzed the molecular and cellular studies. NB-B and KP coordinated the collection of clinical and imaging data. JM, BB, CF-B, SL, OD, SO, IR, LBJ, FR, LP, DG, YM, NB, NL, YS, GM, FG, NP, CV, PVB, HM and CB helped in selecting patients, clinical, histopathological and imaging data. FA, AB, RO and J-FD performed and coordinated the WES procedure (library generation, exome enrichment and sequencing). CM and PN performed the bioinformatics analysis of exome sequencing data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zillhardt, J., Poirier, K., Broix, L. et al. Mosaic parental germline mutations causing recurrent forms of malformations of cortical development. Eur J Hum Genet 24, 611–614 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2015.192

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2015.192

This article is cited by

-

Insights on the Role of α- and β-Tubulin Isotypes in Early Brain Development

Molecular Neurobiology (2023)

-

The clinical-phenotype continuum in DYNC1H1-related disorders—genomic profiling and proposal for a novel classification

Journal of Human Genetics (2020)