Abstract

Background/Objectives:

The degree of misclassification of obesity and undernutrition among elders owing to inaccurate height measurements is investigated using height predicted by knee height (KH) and demispan equations.

Subjects/Methods:

Cross-sectional investigation was done among a random heterogeneous sample from five municipalities in Southern Sweden from a general population study ‘Good Aging in Skåne’ (GÅS). The sample comprised two groups: group 1 (KH) including 2839 GÅS baseline participants aged 60–93 years with a valid KH measurement and group 2 (demispan) including 2871 GÅS follow-up examination participants (1573 baseline; 1298 new), aged 60–99 years, with a valid demispan measurement. Participation rate was 80%. Height, weight, KH and demispan were measured. KH and demispan equations were formulated using linear regression analysis among participants aged 60–64 years as reference. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated in kg/m2.

Results:

Undernutrition prevalences in men and women were 3.9 and 8.6% by KH, compared with 2.4 and 5.4% by standard BMI, and more pronounced for all women aged 85+ years (21% vs 11.3%). The corresponding value in women aged 85+ years by demispan was 16.5% vs 10% by standard BMI. Obesity prevalences in men and women were 17.5 and 14.6% by KH, compared with 19.0 and 20.03% by standard BMI. Values among women aged 85+ years were 3.7% vs 10.4% by KH and 6.5% vs 12.7% by demispan compared with the standard.

Conclusions:

There is an age-related misclassification of undernutrition and obesity attributed to inaccurate height estimation among the elderly. This could affect the management of patients at true risk. We therefore propose using KH- and demispan-based formulae to address this issue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is a strong association between malnutrition and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.1,2 Malnutrition is often associated with sarcopenia3 and is regarded as an independent risk factor of cardiomyopathies (atrophy and hypertrophy). Reduced cardiac contractility and atherosclerosis has also been reported among malnourished geriatric patients. It increases the risk of cardiac failure in end-stage renal disease patients and mortality among cardiac failure patients.4 In addition to sarcopenia, aging is associated with fat redistribution with regional or central adiposity and loss of appendicular fat.3, 5, 6, 7 This is seen as a risk factor for myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, heart disease and hypertension among the elderly.3 Obesity cardiomyopathy has been reported to affect cardiac function resulting from cardiac adaptation to excess body fat.8 Therefore, nutritional assessment among healthy elderly and those with cardiovascular disorders becomes crucial. For this, an accurate body mass index (BMI) and true classification of nutritional status are very important. On the contrary, standard BMI classification criteria for elderly are generally missing.

BMI is an integral part of anthropometric assessments, a widely used indicator to assess nutritional status.9,10 Stature and body weight are important parameters to assess BMI that is a ratio between the weight (in kg) and height (in m2). Inaccurate height measurements lead to BMI misclassification.

Standing height is often directly measured using a linear scale. However, among the elderly, physiological and pathological changes including vertebral flattening and fractures, compression and attrition of intervertebral discs, dorsal kyphosis, scoliosis, bowing of legs and flattening of the plantar arch,5,11 and being bedridden lead to inaccurately lowered height measurement that overestimates BMI12,13 and thereby results in discrepant prevalence rates of undernutrition and obesity.

Surrogate stature measurement methods using sliding calipers, self-reporting of height and predictions using regression equations have been reported.7, 13, 14, 15 Sliding calipers, although usable among recumbent patients, are prone to errors among kyphotic patients.13 Self-reporting is subject to recall bias.16,17 Formulae exist to estimate height using proxy indicators such as arm span, ulnar length, demispan and knee height (KH),11,12,14,15,18, 19, 20, 21, 22 as limb skeleton is less prone to degenerative changes than spinal structures.21

Demispan and KH are two commonly used surrogates to estimate height owing to their slow decrease with age.4 Population- and ethnicity-specific equations have been developed, and in most cases they are applicable only to the population described.11,12,19,23, 24, 25, 26, 27 The most widely used equations are Bassey’s demispan equations, which are derived from a sample of 125 European adults of ∼30 years of age,14 and Chumlea’s KH equations, which are formulated from a large nationally representative sample of 4750 elderly aged 65+ years, specific for the different races (Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites and blacks) in the United States.15 However, the applicability of Bassey’s demispan equations has been debatable owing to the age of the population and the small sample size.13 Chumlea’s equation could be comparatively considered strong based on the large sample size, yet the international applicability of the ethnicity-specific equations remains questionable.

Hence, sex-specific, age-adjusted population-specific equations from large nationally representative samples are needed.13 Based on our literature search, in Sweden, there have been no KH/ demispan-based equations to estimate height and true BMI classification among the elderly. The aim of this paper is to investigate the degree of BMI misclassification using a large national cohort of Swedish elderly and age-adjusted, sex-specific KH and demispan equations.

Materials and methods

Study population

A cross-sectional study was conducted among participants aged ⩾60 years in a longitudinal, randomized, general population-based study called ‘Good Aging in Skåne’ (GÅS), part of the Swedish National Study on Aging and Care (SNAC).28,29 This study involves a heterogeneous sample of men and women from five municipalities of Scania. The National Population Registry was used to randomly invite the participants by letter. Predefined target populations were invited for the age cohorts 60, 66, 72, 78, 81, 84, 87, 90 and 93 years, with an oversampling of the youngest and the oldest cohorts.

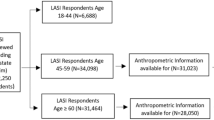

The sample comprised two groups. The first group (group 1) consisted of 2839 elderly participants (aged 60–93 years), 58% of the randomly invited general population residents who accepted to participate in the baseline investigation of GÅS in 2001–2004 and had valid KH measurement.

The second group (group 2) included 2871 participants aged 60–99 years, 1573 from baseline and 1298 new participants who took part in the follow-up examination of GÅS conducted in 2007–2010 (participation rate: 80%) and had a valid demispan measurement. A total of 92 participants were excluded from group 1 and 490 from group 2 because they had missing KH and demispan values, respectively.

Data collection

All participants were examined at a research center, except if they were frail (home visits), after informed consent was obtained. Survey, medical examination and physical functioning tests were conducted by qualified physicians and nurses. An informed consent was obtained. The close-ended questionnaire investigated sociodemographics, physical, mental health and social factors. The descriptive variables included age, sex, place of birth, marital status, education, alcohol consumption, smoking habits and physical activity. These data were obtained from the survey. The marital status denoted whether the participants were single, married, divorced or living with a partner. Education was stratified as primary, secondary, higher secondary or university level. Smoking status indicated whether the participants were regular or irregular smokers or had quit smoking. Alcohol frequency included responses as ‘have never drunk’, ‘a few times in the last year but not since last month’ and ‘have had alcohol a few times in the last month’. The degree of physical activity was investigated in terms of the degree or intensity of training and categorized into barely physically active (‘nothing at all’, ‘very light activity/mostly sedentary’), mild (‘around 2–4 h a week’), moderate (‘1–2 h a week’), heavy (‘at least 3 h a week’) and very heavy (‘regularly or several times a week’).

Anthropometric measurements

Height, weight, KH and demispan were measured based on validated protocols.30, 31, 32 The height was measured using a measuring tape with the individual standing erect with shoulder blades, buttocks and heels against a wall and straight fixed gaze. Arms were along the sides, shoulders relaxed, legs straight, knees touching each other, feet flat and heels together. Readings were made in cm with one decimal value. Bedridden patients and those using a wheel chair were excluded from our study.

Weight (in kg) was measured with a precision balance in the morning with light clothes and no shoes after voiding bowels and bladder.

KH (in cm) was measured using a caliper consisting of a vertical scale with two horizontal blades at each end. The subject was in a recumbent position, with neck and back relaxed, left leg lifted and knee bent at 90°. One of the caliper blades was positioned under the heel of the left foot and the other was placed on the anterior surface of the left thigh just above the condyles of the femur and just proximal to the patella. The shaft of the caliper was held parallel to the shaft of the tibia, and gentle pressure was applied to the blades of the caliper. The measurement was repeated twice and the average was noted. If seated, the leg was supported so that the knee and ankle were at a 90° angle.

Demispan (in cm) was measured with the subject standing upright with back straight, arms extended sideward at 90° to the torso, fingers stretched and the arm rested against a wall to avoid forward or backward bending. The distance between the tip of the middle finger (not nail tip) and midpoint on the sternal notch was noted using a flat, stiff tape that avoids flexion errors.

Measurements were made on the left side unless there was previous amputation, paralysis or contracture.

Statistical analyses

Mean differences between measured and estimated height (Heightdemispan, HeightKH) across 5-year age groups were examined using analysis of variance test. Test for normality was performed for each variable, and the analysis of the residual error term raised no concern. Simple linear regression analysis was performed by including men and women aged 60–64 years as a reference population, because minimal age-related height change is expected. KH- and DS-based equations specific for men and women were formulated with measured height as the dependent variable (Y) and DS (X1) or KH (X2) as the independent variable, respectively. The equations obtained were based on the following formula: Y= Constant+Bi*Xi+ error term, i=1, 2. The constants, as well as the slopes B1 and B2, were estimated. The equations were then applied to other age groups to calculate the predicted height based on KH (HeightKH) and DS (Heightdemispan) at different ages. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 (IBM Corp 2013, Armonk, NY, USA) was used. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

There were 2839 participants in group 1 and 2871 participants in group 2, with a mean age of 71±10.4 years (sex difference not significant).

Group 1 comprised 44.2% men, 55.8% women, 53.6% married, 13.3% smokers, 24.4% who consumed alcohol at least until last month, 8.3% who were barely physically active, 24.9% who reported moderate activity (1–2 h/week) and 3.2% with less than primary education.

Group 2 included 44.4% men, 55.6% women, 62.4% married, 39.5% smokers, 33.2% who consumed alcohol at least until last month, 6.9% who were barely physically active, 26.4% with moderate activity and 1.7% with less than primary education. A sociodemographic comparison between participants and dropouts showed no significant difference (results not shown).

Mean height, weight, KH, demispan, HeightKH and Heightdemispan are shown in Table 1. Mean measured height decreases by ∼6.2 cm among men and 7.8 cm among women from 60–64 to 85+ years of age. This is calculated by the average difference between the mean heights of age groups from 60–64 years to 85+ years in groups 1 and 2 for men and women, respectively. Demispan decreases after 70–74 years by 2.7 cm in men and 1.5 cm in women. The ratio between KH and Height and the ratio between demispan and Height increase with age among women, however only demispan: Height ratio increases with age among men.

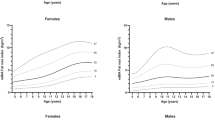

Figures 1a and b demonstrates the sex-specific regression equations to estimate the predicted body height based on KH and DS, respectively.

Regression equations used to predict stature using knee height (a) and demispan (b) of elderly men (i) and women (ii) aged 60–64 years. The respective regression lines are shown. Knee height method: a(i) height=115.23+1.16 × knee height (men); a(ii) height=104.52+1.23 × knee height (women). Demispan method: b(i) height=49.41+1.4 × demispan (men); b(ii) height=36.34+1.53 × demispan (women).

KH-based equations:

Demispan-based equations:

Age- and sex-stratified measured and predicted heights and estimated and predicted BMI are shown in Table 2.

HeightKH is higher than measured height in both sexes and each age group, notably from ⩾65–69 years of age, and the difference tends to increase with age. Consequently, BMIKH is lower than BMI among each age group in both sexes. The difference between BMI and BMIKH is 0.45 kg/m2 among men and 0.98 kg/m2 among women.

Heightdemispan is higher than measured height in both sexes, with notable difference at and after 70–74 years of age, and increasing with age. The difference between BMI and BMIdemispan is 0.15 kg/m2 in men and 0.5 kg/m2 in women.

The prevalence of undernutrition and obesity based on BMI, BMIKH and BMIdemispan are shown in Table 3 (also see Figure 2).

According to BMI, undernutrition prevalence is 2.4% in men and 5.4% in women. In particular, predicted BMIKH indicates higher prevalence of undernutrition than BMI using measured height in men (mean: 3.9%) and women (mean: 8.6%) and among every age group category. Undernutrition prevalence is twice as high in 80–84 and 85+ years of age compared with BMI assessment. Women aged 85+ years have undernutrition prevalence of 21.3% by BMIKH compared with 11.3% by BMI.

BMIKH estimated overall obesity prevalence is 17.5% in men and 14.6% in women and is lower than BMI. Sex difference between BMI and BMIKH can be noted at different age groups. Among men, it is notable at 80–84 years of age and among women it is notable as early as 70–74 years of age (26.2% by BMI and 17.1% by BMIKH). BMIKH estimates among men aged 80–84 years (7.4%) are almost half of that estimated by BMI (16.5%). At 85+ years, the BMIKH obesity prevalence is further lower (4.9%); that is, when BMI classifies 1 in 10 men as obese, it is 1 in 20 according to BMIKH. In addition, when 2 in 10 women aged 80–84 years are obese by BMI, only 1 in 10 is according to BMIKH.

For comparison, we tried to apply the Chumlea’s KH equation to calculate BMIChumlea. Undernutrition among women aged 85+ years was 7.3% compared with 21.3% using the BMIKH and 11.3% using BMI (results not shown).

BMIdemispan undernutrition prevalence is estimated to be higher than that by BMI. Among men, there is little or no difference in prevalence rates between the two methods at each group, except at the age of 65–69 years, where BMIdemispan gives higher value (2.1%) than BMI (1.5%). However, among women aged 85+ years, there is 16.5% undernutrition by BMIdemispan compared with 10% by BMI.

Overall obesity prevalence estimated by BMIdemispan is lower than that by BMI in both sexes.

For example, the values are as follows: 16.7% by BMI vs 10.9% by BMIdemispan among men aged 80–84 years. Among women aged 75–79 years, it is 24.6% by BMI vs 18.2% by BMIdemispan. BMI-estimated obesity prevalence is almost twice that estimated by BMIdemispan among the participants aged 85+ years, with small or no difference in younger groups.

Discussion

We investigated the degree of misclassification of obesity and undernutrition owing to inaccurate height estimates used in BMI calculations among the elderly in Southern Sweden. We addressed this problem by developing KH- and demispan-based age-adjusted and sex-specific equations derived from a large nationally representative general population sample. Studies have shown that direct method underestimates body height measurement among geriatric populations,14,15 and KH and demispan are used as surrogate measures.20,21,25,33

The study of Hirani and Mindel27 showed that in men aged 70+ years, BMI calculated using measured height was significantly higher than BMI using height predicted on the basis of demispan, which was the case among women aged 65+ years. The prevalence of underweight (BMI <20 kg/m2) was significantly lower by 9.4% when using measured height to calculate BMI in those aged 80+ years. Overestimation of obesity prevalence by direct height BMI among those aged 80+ years was 9.8% and among those aged 70–74 years old it was 7.2%.

Hence, race-specific equations from large and representative population samples are needed to accurately estimate BMI among the elderly.19,22 The clinical significance of BMI misclassification calls for attention to the use of not only age-, sex- and country-specific but also ethnicity-specific population data for such equations.

In this study, we used 60–64 years of age as reference to formulate the equations. We found that the direct method underestimated the height compared with those predicted by KH and demispan. Height decreased with age, especially among women, and the difference between the direct and predicted height widens with age. Concordant results were found in other population studies using KH and/or demispan to estimate height.13,21,24,34 This could be attributed to conditions like kyphoscoliosis that cause underestimation of measured height and higher likelihood of osteoporosis among women accounting for the difference in height loss between sexes.5 The widening difference between measured height and predicted height can be owing to the fact that vertebral degeneration increases with age, leading to stature underestimation among the oldest olds.35 This is, however, addressed by age-adjusted estimation of predicted height for the age categories (60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84 and 85+ years). The difference could even be a cohort effect where there is increasing height among younger cohorts.20,36, 37, 38, 39

The agreement analysis of Weinbrenner et al.23 to test the correlation between measured height and demispan-estimated height showed no significant difference between the methods (−0.03 cm in men and −0.02 in women). These results are applicable to the defined Spanish population group and denote variability in anthropometry and relative body proportions with race and ethnicity.

The standard method of BMI calculation includes weight in kg divided by measured height in m2. Predicted BMI was calculated by substituting predicted height based on KH and demispan. Our findings revealed a notable impact of the measured height on BMI classification, giving an underestimation of undernutrition and overestimation of obesity among Swedish elderly. This is in agreement with studies among the elderly population aged ⩾65 years in a Swedish hospital setting, and noninstitutionalized nationally representative cross-sectional study from the Health Survey for England (HSE), 2001.9,13 In comparison with our study results, the prospective study of Johansson et al.40 among home-living Swedish elderly population showed that the prevalence of risk for malnutrition assessed by Mini Nutritional Assessment was 14.5% (18.8 among women and 10.6% among men). It is also known that functionally dependent home-living older people have a higher risk of developing malnutrition.41

Undernutrition defined by BMI ⩽20 kg/m22 is evidently underestimated by BMIdemispan among both the youngest (60–64 years) and the oldest (85+ years) age groups. The prediction method better captures undernutrition, especially among the most elderly,1,42,43 when height changes are most severe because of functional impairments.42

BMIKH detects marked undernutrition prevalence among men aged ⩾80 years and women aged ⩾70 years. In women, hormonal changes during the postmenopausal phase lead to earlier osteoporosis, bone loss fat redistribution,5 functional dependence and undernutrition.44

The average prevalence of undernutrition among those hospitalized and in special accommodations in Sweden after 1990 is 31.8%,45 and elderly undernutrition prevalence rises globally owing to complex somatic, psychic and social determinants.1,46 The morbidity and mortality risks of low BMI are well established among Swedish women31 and other elderly populations.42,43,47

Obesity (BMI ⩾30 kg/m2)5 is overestimated by standard measurements. We found that BMI-calculated obesity prevalence is twice as high as KH- and demispan-based among men aged 80+ years and women aged 70+ years, and it doubles with every decade thereafter. As discussed above, this is attributed to the loss of height owing to degenerative conditions.

Our demispan observations were concordant with those from the study by Hirani and Aresu19 among noninstitutionalized elderly and with those from the study by Frid et al.9 among hospitalized elderly. However, statistical testing for agreement was done in these and other similar studies that compared the use of demispan or KH instead of measured height.

BMIdemispan did not show as a wide variation from BMI as BMIKH. This could be explained by survival bias and possible birth cohort differences.38,39 The sample used for demispan analysis was partly participants from the baseline examination. It could be possible that the mix of birth cohorts formed a group with relatively less height-altering conditions. This kind of selection bias should merely reduce variation due to misclassification in the reference group. On the other hand, the prevalence of undernutrition among the elderly age groups in the general population might be higher.

Some studies report a relatively limited impact of obesity among elderly women and men.42,48 This has often been explained by aging-related alterations in body composition, namely the fat-free mass loss and visceral fat redistribution. High BMI values (overweight, but not obesity) can be protective for the elderly,49 but other anthropometric measurements such as waist circumference and waist hip ratio may need to be accounted for along with BMI, but correct BMI measurements are nevertheless important for risk estimations.

The main strength of our study is the large population sample that is nationally representative owing to a random age- and gender-stratified selection and inclusion of both urban and rural areas. Substantial anthropometric differences between rural and urban populations exist, the former being heavier and having more muscle mass.50 The equations developed are the first among the Swedish population. A significant limitation is due to the cohort effect, namely the difference in height between the oldest and the youngest age groups owing to an increasing generational height. We aim to test this in a forthcoming follow-up study. We have attempted to adjust for the height reduction due to aging by calculating prediction equations among 60–64-year-old group, the youngest in our study sample, and then applying it to other age groups. Second, applying our equations to other populations requires a thorough understanding of anthropometric characteristics and differences.

Population studies widely use BMI because it is a comparatively easy and cost-effective nutritional assessment tool. Hence, accuracy is needed to avoid differential misclassification bias. These equations are especially recommended in evaluating malnutrition prevalence in epidemiological studies in community settings.

In conclusion, there is an age-related misclassification of undernutrition and obesity among the elderly. It is attributed to caveats of inaccurate height estimation among the elderly. We have proposed the use of sex-specific and age-adjusted prediction equations of body height based on knee height and demispan to address this issue.

References

Pirlich M, Lochs H . Nutrition in the elderly. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 15: 869–884.

Kuczmarski RJ . Need for body composition information in elderly subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 1989; 50: 1150–1157.

Hickson M . Malnutrition and ageing. Postgrad Med J 2006; 82: 2–8.

de Groot LC, Verheijden MW, de Henauw S, Schroll M, van Staveren WA SENECA Investigators. Lifestyle, nutritional status, health, and mortality in elderly people across Europe: a review of the longitudinal results of the SENECA study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2004; 59: 1277–1284.

Perissinotto E, Pisent C, Sergi G, Grigoletto F ILSA Working Group (Italian Longitudinal Study on Ageing). Anthropometric measurements in the elderly: age and gender differences. Br J Nutr 2002; 87: 177–186.

Dey DK, Rothenberg E, Sundh V, Bosaeus I, Steen B . Body mass index, weight change and mortality in the elderly. A 15 y longitudinal population study of 70 y olds. Eur J Clin Nutr 2001; 55: 482–492.

Beaufrere B, Morio B . Fat and protein redistribution with aging: metabolic considerations. Eur J Clin Nutr 2000; 54: 48–53.

Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, Hong Y, Stern JS, Pi-Sunyer FX, Eckel RH . Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2006; 26: 968–976.

Frid H, Thors Adolfsson E, Rosenblad A, Nydahl M . Agreement between different methods of measuring height in elderly patients. J Hum Nutr Diet 2013; 26: 504–511.

World Health Organization. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO expert committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1995; 854: 1–452.

Siqueira Vde O, Costa BV, Lopes AC, Santos LC, Lima-Costa MF, Caiaffa WT . Different equations for determining height among the elderly: The Bambui cohort study of aging. Cad Saude Publica 2012; 28: 125–134.

Karadag B, Ozturk AO, Sener N, Altuntas Y . Use of knee height for the estimation of stature in elderly Turkish people and their relationship with cardiometabolic risk factors. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2012; 54: 82–89.

Hirani V, Mindell J . A comparison of measured height and demi-span equivalent height in the assessment of body mass index among people aged 65 years and over in England. Age Ageing 2008; 37: 311–317.

Bassey EJ . Demi-span as a measure of skeletal size. Ann Hum Biol 1986; 13: 499–502.

Chumlea WC, Roche AF, Steinbaugh ML . Estimating stature from knee height for persons 60 to 90 years of age. J Am Geriatr Soc 1985; 33: 116–120.

Taylor AW, Dal Grande E, Gill TK, Chittleborough CR, Wilson DH, Adams RJ et al. How valid are self-reported height and weight? A comparison between CATI self-report and clinic measurements using a large cohort study. Aust N Z J Public Health 2006; 30: 238–246.

Ziebland S, Thorogood M, Fuller A, Muir J . Desire for the body normal: body image and discrepancies between self reported and measured height and weight in a British population. J Epidemiol Community Health 1996; 50: 105–106.

Reeves SL, Varakamin C, Henry CJ . The relationship between arm-span measurement and height with special reference to gender and ethnicity. Eur J Clin Nutr 1996; 50: 398–400.

Hirani V, Aresu M . Development of new demi-span equations from a nationally representative sample of older people to estimate adult height. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60: 550–554.

Hirani V, Tabassum F, Aresu M, Mindell J . Development of new demi-span equations from a nationally representative sample of adults to estimate maximal adult height. J Nutr 2010; 140: 1475–1480.

Hickson M, Frost G . A comparison of three methods for estimating height in the acutely ill elderly population. J Hum Nutr Diet 2003; 16: 13–20.

Chumlea WC, Guo SS, Wholihan K, Cockram D, Kuczmarski RJ, Johnson CL . Stature prediction equations for elderly non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Mexican-American persons developed from NHANES III data. J Am Diet Assoc 1998; 98: 137–142.

Weinbrenner T, Vioque J, Barber X, Asensio L . Estimation of height and body mass index from demi-span in elderly individuals. Gerontology 2006; 52: 275–281.

Cereda E, Bertoli S, Vanotti A, Battezzati A . Estimated height from knee-height in Caucasian elderly: implications on nutritional status by mini nutritional assessment. J Nutr Health Aging 2010; 14: 16–22.

Bermúdez OI, Becker EK, Tucker KL . Development of sex-specific equations for estimating stature of frail elderly Hispanics living in the northeastern United States. Am J Clin Nutr 1999; 69: 992–998.

Knous BL, Arisawa M . Estimation of height in elderly Japanese using region-specific knee height equations. Am J Hum Biol 2002; 14: 300–307.

Hirani V, Mindell J . A comparison of measured height and demi-span equivalent height in the assessment of body mass index among people aged 65 years and over in England. Age Ageing 2008; 37: 311–317.

Mendoza-Nunez VM, Sanchez-Rodriguez MA, Cervantes-Sandoval A, Correa-Munoz E, Vargas-Guadarrama LA . Equations for predicting height for elderly Mexican Americans are not applicable for elderly Mexicans. Am J Hum Biol 2002; 14: 351–355.

Ekström H, Elmståhl S . Pain and fractures are independently related to lower walking speed and grip strength: results from the population study “Good Ageing in Skåne”. Acta Orthop 2006; 77: 902–911.

Lagergren M, Fratiglioni L, Hallberg IR, Berglund J, Elmståhl S, Hagberg B et al. A longitudinal study integrating population, care and social services data. The Swedish National study on Aging and Care (SNAC). Aging Clin Exp Res 2004; 16: 158–168.

Gibson R . Nutritional Assessment: A Laboratory Manual. Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 1993.

Gibson R . Principles of Nutritional Assessment. Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 1990.

Socialstyrelsen (National Board of Health and Welfare). Nutritional Problems in Health Care. Prevention and Treatment (in Swedish). Näringsproblem i vård och omsorg. Prevention och behandling. SoS Rapport 2000:11: Stockholm, Sweden, 2000.

Ozer BK, Gultekin T, Sagir M . Estimation of stature in Turkish adults using knee height. Anthropol Anz 2007; 65: 213–222.

Urban JP, Roberts S . Degeneration of the intervertebral disc. Arthritis Res Ther 2003; 5: 120–130.

Cavelaars AE, Kunst AE, Geurts JJ, Crialesi R, Grotvedt L, Helmert U et al. Persistent variations in average height between countries and between socio-economic groups: an overview of 10 European countries. Ann Hum Biol 2000; 27: 407–421.

Cernerud L, Lindgren GW . Secular changes in height and weight of Stockholm schoolchildren born in 1933, 1943, 1953 and 1963. Ann Hum Biol 1991; 18: 497–505.

Statistiska Centralbyrån (Statistics Sweden). Living conditions survey. BMI, height and weight averages 1988-89, 2009-2011. Tables and graphs (in Swedish). Undersökningarna av levnadsförhållanden (ULF/SILC). BMI, längd och vikt- medelvärden 1988-89, 2009-2011. Tabeller och diagram. URL http://www.scb.se/Pages/ProductTables____341406.aspx. Accessed 26 October 2013.

Pliktverket. Results from inspection. Statistics from 2000. Report. (in Swedish). Resultat från mönstringar. Statistik från 2000. Pliktverket: Karlstad, Sweden, 2000 pp 5–7.

Johansson Y, Bachrach-Lindström M, Carstensen J, Ek AC . Malnutrition in a home-living older population: prevalence, incidence and risk factors. A prospective study. J Clin Nurs 2009; 18: 1354–1364.

Visvanathan R, Macintosh C, Calary M, Penhall R, Horowitz M, Chapman I 2003. The nutritional status of 250 older recipients of domiciliary care services and its association with outcomes at 12 month. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003; 51: 1007–1011.

Dey DK, Rothenberg E, Sundh V, Bosaeus I, Steen B . Height and body weight in elderly adults: a 21-year population study on secular trends and related factors in 70-year-olds. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001; 56: 780–784.

Harris D, Haboubi N . Malnutrition screening in the elderly population. J R Soc Med 2005; 98: 411–414.

Bachrach-Lindstrom MA, Ek AC, Unosson M . Nutritional state and functional capacity among elderly Swedish people with acute hip fracture. Scand J Caring Sci 2000; 14: 268–274.

Elmståhl S. Undernutrition- Prevelence and Incidence. In: Nutritional Problems in Health Care (in Swedish). Undernäring- Prevalens och Incidens. Näringsproblem i vård & omsorg: Prevention och behandling: SoS-rapport. Socialstyrelsen: Stockholm, Sweden, 2000, pp 110–117.

Brownie S . Why are elderly individuals at risk of nutritional deficiency? Int J Nurs Pract 2006; 12: 110–118.

Tierney AJ . Undernutrition and elderly hospital patients: a review. J Adv Nurs 1996; 23: 228–236.

Eiben G, Dey DK, Rothenberg E, Steen B, Bjorkelund C, Bengtsson C et al. Obesity in 70-year-old Swedes: secular changes over 30 years. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005; 29: 810–817.

Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R . Body mass index is inversely related to mortality in older people after adjustment for waist circumference. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 2112–2118.

Elmståhl S, Gärdsell P, Ringsberg K, Sernbo I . Body composition and its relation to bone mass and fractures in an urban and a rural population. Aging (Milano) 1993; 5: 47–54.

Acknowledgements

The project Good Aging in Skåne (GÅS), part of the Swedish National study on Aging and Care (SNAC), was supported by the Swedish Ministry of Social Affairs, the county Region Skåne, the Medical faculty at Lund University and the Vårdal Institute.

Author Contributions

NNG contributed to study design, analysis and interpretation of data and preparation of manuscript; MP contributed to study design and preparation of the manuscript; SE contributed to study concept and design, acquisition and maintenance of study cohort, analysis and interpretation of data and preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Gavriilidou, N., Pihlsgård, M. & Elmståhl, S. High degree of BMI misclassification of malnutrition among Swedish elderly population: Age-adjusted height estimation using knee height and demispan. Eur J Clin Nutr 69, 565–571 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2014.183

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2014.183

This article is cited by

-

Plasma transthyretin is a nutritional biomarker in human morbidities

Frontiers of Medicine (2022)

-

Anthropometric reference data for elderly Swedes and its disease-related pattern

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2015)