Abstract

Background/Objectives:

Malnutrition is present in 20–50% of hospitalized patients, and nutritional care is a challenge. The aim was to evaluate whether the implementation of a nutritional strategy would influence nutritional care performance in a university hospital.

Subjects/Methods:

This was a prospective quality improvement program implementing guidelines for nutritional care, with the aim of improving nutritional practice. The Nutrition Risk Screening (NRS) 2002 was used. Point prevalence surveys over 2 years to determine whether nutritional practice had improved.

Results:

In total, 3604 (70%) of 5183 eligible patients were screened and 1230 (34%) were at nutritional risk. Only 53% of the at-risk patients got nutritional treatment and 5% were seen by a dietician. The proportion of patients screened increased from the first to the eighth point prevalence survey (P=0.012), but not the proportion of patients treated (P=0.66). The four initial screening questions in NRS 2002 identified 92% of the patients not at nutritional risk.

Conclusions:

Implementation of nutritional guidelines improved the screening performance, but did not increase the proportion of patients who received nutritional treatment. Point prevalence surveys were useful to evaluate nutritional practice in this university hospital. In order to improve practice, we suggest using only the four initial screening questions in NRS 2002 to identify patients not at risk, better education in nutritional care for physicians and nurses, and more dieticians employed. Audit of implementation of guidelines, performed by health authorities, and specific reimbursement for managing nutrition may also improve practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malnutrition is present in 18–55% of hospitalized patients (Sorensen et al., 2008; Imoberdorf et al., 2009). Studies show that nutritional support to undernourished patients and those at nutritional risk is advantageous (Stratton and Elia, 2007). European guidelines state that provision of tailored food should be an integral part of patient care (Council of Europe, 2002; Kondrup et al., 2003a, 2003b; Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2009). However, nutrition is often not given priority in clinical practice (Mowe et al., 2006, 2008). Insufficient knowledge and low commitment among nurses and physicians result in an insufficient focus on nutritional aspects of care (Kondrup et al., 2002; Bavelaar et al., 2008; Mowe et al., 2008). Dietary parameters are seldom monitored during hospital stays; neither are they described in patients' medical records or discharge summaries (Bavelaar et al., 2008; Meijers et al., 2009). It is a great challenge to implement nutritional guidelines in hospitals (Llido, 2006; Mowe et al., 2006, 2008; Bavelaar et al., 2008; Persenius et al., 2008; Liang et al., 2009).

To improve practice at Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway, a campaign entitled ‘Good nutritional practice’ was introduced during 2006. The goals were to increase professional awareness of the importance of nutritional care and to provide proper nutritional care to patients with such needs. To achieve these goals, it was considered necessary to develop guidelines, tools and skills, and to educate nurses and physicians in basic clinical nutrition. Responsibilities were defined and a professional framework was established (Figure 1) to implement these aspects of nutritional care. An important factor was to increase the flexibility of the food services, leading to the provision of more tempting and nourishing food according to patient needs.

The aim of the present study was, by using repeated point prevalence surveys, to evaluate whether the implementation of a new strategy had positive effects on nutritional care in the hospital.

Materials and methods

We performed a prospective quality improvement program implementing nutritional guidelines through the dedicated nutritional network (Figure 1). Repeated point prevalence surveys over 2 years made it possible to assess whether practice changed over time. The first survey was performed on 31 January 2008 in 14 hospital departments. The seven further surveys were conducted in 51 departments between June 2008 and November 2009. All hospital departments participated except obstetrics, children's and the psychiatric wards. Patients were excluded if they were admitted for bariatric surgery, day-surgery or other day-care procedure. Other exclusion criteria were terminal care and age below 18 years.

Implementing of guidelines

The barriers to proper nutritional care identified by the Council of Europe (Council of Europe, 2002) were taken into account when the nutritional campaign was carried out. Health care professionals, kitchen staff, patients' representatives and the hospital management were involved in workshops or the network. The aim was to integrate proper nutrition in patients' care. The nutritional network included 130 physicians, nurses and nurse assistants, and were organized in three levels (Figure 1). They were educated for 2 days in basic clinical nutrition and were then responsible for introducing the guidelines to their units. They were then invited to monthly meetings for 1 year. Kick-off seminars, courses and repeating mini-screening schools were enrolled. Mealtime routines and kitchen services were improved, and supplements were more available. Other amenities included interactive tools like website, e-course in clinical nutrition and dedicated forms in electronic patient journal system.

The point prevalence surveys

At 0800 hours on the day of registration, administrative patient's data (name, date of birth, sex and hospital ward) were transferred to a dedicated database. The patients were first included (Supplementary Information sheet 1, Appendix 1), then screened according to the Nutrition Risk Screening 2002 (NRS 2002) (Supplementary Information sheet 2, Appendix 1). If total score was ⩾3, additional questions about nutritional support were answered (Supplementary Information Sheet 3, Appendix 1).

Outcomes

The primary outcome in this study was change in clinical practice. This was measured as the proportion of patients screened, proportion of patients at nutritional risk with a nutritional plan, that is, who were either under treatment or for whom treatment was planned, and the proportion of patients seen by a dietician. We used the proportion of patients coded with the diagnoses for under nutrition according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) E44 or E46 (World Health Organization, 2010) to assess the participation by physicians. This information was retrieved from the electronic patient database. The secondary outcome is the prevalence of nutritional risk at the hospital.

Statistics

Statistical evaluation included a descriptive analysis, and estimations of prevalence of undernutrition at each survey and the proportion of patients who underwent nutritional treatment. Data analysis was performed using the statistical software of SAS Institute Inc., Version 9.1 and SPSS Version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL,USA).

Ethics

This study was part of a quality improvement project and was exempted from review by Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics. The study was approved by the data inspectorate and the hospital research board. The patients were not asked to give informed consent, as they were not subject to any experimental interventions.

Results

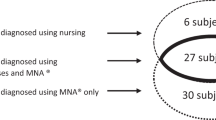

Of the total number of 5849 inpatients on the eight occasions, 666 (11%) did not meet the inclusion criteria, and for 1579 patients (27%), the screening was not completed. A total of 3604 (70%) patients were screened (Figure 2). The proportion of patients screened increased significantly from the first to the last survey, with a range from 54–77% (Figure 3, P=0.012).

The prevalence of nutritional risk was 56% at the first point prevalence survey (January 2008) and varied between 30–36% at the subsequent surveys (Table 1). In total 1230 patients were identified to be at nutritional risk during the eight surveys. Of these, 743 (60%), had a nutritional treatment plan. In 649 cases (53%), the nutritional intervention was started and in 94 cases (7%) nutritional treatment was pending (Figure 2). The proportion of patients receiving a nutritional treatment plan varied between 54 and 68%, and did not increase during the eight surveys (P=0.66). Those who already received nutritional treatment varied between 47 and 59% over time, and patients at risk whose nutritional treatment was planned but had not yet commenced varied between 5 and 11% during the surveys. Only 62 (5%) of the patients at nutritional risk were evaluated and followed up by a dietician.

During 2008 and 2009, 1.3% of all adult, somatic inpatients at the hospital were diagnosed with malnutrition diagnoses (E44 or E46). In this study, 649 patients (14.3%) of the eligible patients (n=5183) were qualified for this (at nutritional risk and have got nutritional treatment), and 487 (9.3%) more were in need for such treatment (at nutritional risk and did not get nutritional treatment).

NRS 2002 identified 2374 patients (66%) not at nutritional risk. Of these, 2180 were identified by the four initial questions (Figure 2), while the other 194 were considered not at risk according to the remaining NRS 2002 questions, giving a specificity of 92% to identify not-at-risk patients, with the first four questions. The main screening was performed for 1424 patients.

Discussion

This study showed improved screening performance after implementing nutritional guidelines in a university hospital. This is an important element to achieve better nutritional care. One in three screened patients were at nutritional risk, but only half of the people at risk received nutritional treatment, with no improvement during the study period.

The strengths of this study include a large sample of patients and almost complete coverage of relevant wards and patient categories. We used a validated screening tool and the screening data were reported by a standardised electronic form designed for this purpose. An important limitation is that the point prevalence surveys were initiated more than 1 year after the start of the nutritional campaign, and initial changes in nutritional practice could then be undetected. Ideally the surveys should have been initiated before the campaign started. A possible limitation is that the point prevalence surveys themselves must be considered to be, at the same time, both interventions and measurements of the results of these interventions, because, as screening is supposed to improve nutritional practice, it is also a reminder of better nutritional practice. This is supported by the fact that results from repeated point prevalence surveys of hospital infections have demonstrated improved clinical practice (Scheel and Stormark, 1999; Sartor et al., 2005).

Although screening performance improved, the most important outcome, namely the proportion of patients at nutritional risk who received a nutritional treatment plan did not increase. It could be a problem that information about patients at nutritional risk were not communicated from the nurses who did the screening to the nurses and physicians who were responsible for giving nutritional treatment. Another factor is a limited dietician service in the hospital The number of dieticians/clinical nutritionists in Norwegian hospitals is among the lowest in Western countries (Norwegian Health Directorate, 2007), implying that the physicians and nurses mainly are responsible for the patients nutritional care. Nutrition has low priority in the education of medical students in Norway (Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2007) and Norwegian physicians and nurses reported to have less knowledge and interest for clinical nutrition than their Danish and Swedish colleagues (Mowe et al., 2008). The interest in nutritional matters is lower in wards not regularly visited by dieticians (Thoresen et al., 2008). Based on the experience from this study and other recent publications (Mowe et al., 2008), we suggest that there is a scarcity of nutritional knowledge and of dieticians available. We propose that a greater focus on nutritional education of physicians, both undergraduate and postgraduate, and an increased number of dieticians are important to improve nutritional practice.

In Norway, central health authorities have developed clinical guidelines for nutritional care in hospitals and nursing homes. Performing audits of the implementation of these guidelines and economic incentives, such as Diagnosis Related Groups reimbursement for diagnosing malnutrition, may also help improve practice.

Nutritional screening is recommended (Council of Europe, 2002; Kondrup et al., 2003a, 2003b; Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2009 and the hospitals local guidelines) as the first step to individualized nutritional treatment. One reason for not doing such screening is lack of time. Nutritional screening is one of several time-consuming procedures in a busy hospital and may be easy to neglect. By using the four opening questions in NRS 2002 we identified 92% of the patients not at nutritional risk. As all at-risk patients are screened positive on these first four questions of NRS 2002, there will be no patients at risk who are not detected. The proportion of patients classified to be at nutritional risk, would increase from 34 to 40% when using only the four initial questions. Further studies are needed to investigate whether the screening tool could be simplified.

The prevalence of patients at nutritional risk is similar to previous European studies (Rasmussen et al., 2006; Sorensen et al., 2008; Lucchin, 2009) but lower than the 44%, shown by a previous Norwegian study (Oppedal et al., 2010). The difference can be due to a bias in our study because 1579 patients (27%) eligible for screening were not screened. The healthiest patients may have a higher likelihood of being screened, because it can be difficult to weight bedridden patients and patients in wheelchairs. It is also a challenge to obtain reliable information about previous weight and food intake from certain patients, for example, with delirium and dementia. It has been reported that patients without anthropometric information in the medical records have higher morbidity, mortality and length of stay (Stratton et al., 2003; Izawa et al., 2007).

This study was not designed to assess patient outcomes or improvements in food provided to the patients, but there might have been some general improvement in nutrition in the hospital owing to better and more flexible food services.

The point prevalence surveys were easy to perform owing to previous experience with similar surveys on infections. Repeated point prevalence surveys allow trend analyses in clinical nutritional practice. It is a suitable method to draw attention to a common and serious problem in health care and it should be considered as a national quality indicator in clinical nutrition.

Conclusion

Implementation of nutritional guidelines in this university hospital improved the screening performance, which is an important element in better nutritional care, but did not increase the proportion of patients who received nutritional treatment. One of the three patients was at nutritional risk, but only half of them got nutritional treatment. In order to improve practice, we suggest using only the four initial screening questions in NRS 2002 to identify patients not at risk. We also suggest better education in nutritional care for physicians and nurses, and more dieticians employed to achieve more knowledge about nutrition audits of implementation of guidelines performed by health authorities, better accordance between the screening tool and the ICD-10 criteria and specific reimbursement for diagnosing malnutrition may also improve practice. We propose repeated point prevalence surveys to become a national quality indicator in clinical nutrition.

References

Bavelaar JW, Otter CD, van Bodegraven AA, Thijs A, van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA (2008). Diagnosis and treatment of (disease-related) in-hospital malnutrition: the performance of medical and nursing staff. Clin Nutr 27, 431–438.

Council of Europe (2002). Food and Nutritional Care in Hospitals: How to Prevent Undernutrition. Strasbourg Cedex, pp 28, 38, 39, 50.

Imoberdorf R, Meier R, Krebs P, Hangartner PJ, Hess B, Staubli M et al. (2009). Prevalence of undernutrition on admission to Swiss hospitals. Clin Nutr 29, 38–41.

Izawa S, Enoki H, Hirakawa Y, Masuda Y, Iwata M, Hasegawa J et al. (2007). Lack of body weight measurement is associated with mortality and hospitalization in community-dwelling frail elderly. Clin Nutr 26, 764–770.

Kondrup J, Allison SP, Elia M, Vellas B, Plauth M (2003a). ESPEN guidelines for nutrition screening 2002. Clin Nutr 22, 415–421.

Kondrup J, Johansen N, Plum LM, Bak L, Larsen IH, Martinsen A et al. (2002). Incidence of nutritional risk and causes of inadequate nutritional care in hospitals. Clin Nutr 21, 461–468.

Kondrup J, Rasmussen HH, Hamberg O, Stanga Z (2003b). Nutritional risk screening (NRS 2002): a new method based on an analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clin Nutr 22, 321–336.

Liang X, Jiang ZM, Nolan MT, Wu X, Zhang H, Zheng Y et al. (2009). Nutritional risk, malnutrition (undernutrition), overweight, obesity and nutrition support among hospitalized patients in Beijing teaching hospitals. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 18, 54–62.

Llido LO (2006). The impact of computerization of the nutrition support process on the nutrition support program in a tertiary care hospital in the Philippines: report for the years 2000–2003. Clin Nutr 25, 91–101.

Lucchin L (2009). An Italian investigation on nutritional risk in hospital admission: The PIMAY (Project: Iatrogenic MAlnutrition in Italy) study. e-Spen 4, 199–202.

Meijers JM, Halfens RJ, van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA, Dassen T, Schols JM (2009). Malnutrition in Dutch health care: prevalence, prevention, treatment, and quality indicators. Nutrition 25, 512–519.

Mowe M, Bosaeus I, Rasmussen HH, Kondrup J, Unosson M, Irtun O (2006). Nutritional routines and attitudes among doctors and nurses in Scandinavia: a questionnaire based survey. Clin Nutr 25, 524–532.

Mowe M, Bosaeus I, Rasmussen HH, Kondrup J, Unosson M, Rothenberg E et al. (2008). Insufficient nutritional knowledge among health care workers? Clin Nutr 27, 196–202.

Norwegian Directorate of Health (2007). Ernæring i helsetjenesten. Oslo, pp 38, 40. IS-1424, http://www.helsedirektoratet.no/publikasjoner/rapporter/ern_ring_i_helsetjenesten_81004.

Norwegian Directorate of Health (2009). National Guidelines on Preventing and Treatment of Malnutrition. Oslo, pp 76, IS-1580, http://www.helsedirektoratet.no/publikasjoner/nasjonale_faglige_retningslinjer/nasjonale_faglige_retningslinjer_for_forebygging_og_behandling_av_underern_ring_443404.

Oppedal K, Nesvåg S, Pedersen B, Skjøtskift S, Aarstad AKH, Ullaland S et al. (2010). Health and the need for health promotion in hospital patients. Eur J Public Health; e-pub ahead of print 13 October 2010.

Persenius MW, Hall-Lord ML, Baath C, Larsson BW (2008). Assessment and documentation of patients' nutritional status: perceptions of registered nurses and their chief nurses. J Clin Nurs 17, 2125–2136.

Rasmussen HH, Kondrup J, Staun M, Ladefoged K, Lindorff K, Jorgensen LM et al. (2006). A method for implementation of nutritional therapy in hospitals. Clin Nutr 25, 515–523.

Sartor C, Delchambre A, Pascal L, Drancourt M, De Micco P, Sambuc R (2005). Assessment of the value of repeated point-prevalence surveys for analyzing the trend in nosocomial infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 26, 369–373.

Scheel O, Stormark M (1999). National prevalence survey on hospital infections in Norway. J Hosp Infect 41, 331–335.

Sorensen J, Kondrup J, Prokopowicz J, Schiesser M, Krahenbuhl L, Meier R et al. (2008). EuroOOPS: an international, multicentre study to implement nutritional risk screening and evaluate clinical outcome. Clin Nutr 27, 340–349.

Stratton RJ, Elia M (2007). Who benefits from nutritional support: what is the evidence? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 19, 353–358.

Stratton RJ, Green CJ, Elia M (2003). Disease Related Malnutrition: An Evidence-based Approach to Treatment, 1st edn. CABI Publishing: Cambridge, pp 1–34.

Thoresen L, Rothenberg E, Beck AM, Irtun O (2008). Doctors and nurses on wards with greater access to clinical dietitians have better focus on clinical nutrition. J Hum Nutr Diet 21, 239–247.

World Health Organization (2010). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision. http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Kavli Research Centre for Ageing and Dementia, Bergen, Institute of Internal Medicine, University of Bergen, Norway, and Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway. We extend our thanks to the Department of Research and Development, most of all Tore Wentzel-Larsen, Elizabeth Tørressen Nordeide, Kjersti Berge and Kari Sygnestveit for assistance in the planning, acquisition and analyses of the data, Centre of Infection Control and Thor-Ludvig Thorsen for the practical support. We also thank Andreas Henriksen for statistical support and Simon Conroy for important advices in the revision of the manuscript, and the management at Haukeland University Hospital for introducing ‘Good nutritional care’ and for lending practical support to this.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Contributors: RJT, ABG and GST developed the nutritional strategy, conception and design of the study. RJT modified the computer tool, prepared and conducted the surveys, processed and analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All the authors participated in the interpretation of the data, contributed to writing the manuscript and to the final approval of the submitted version.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on European Journal of Clinical Nutrition website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Tangvik, R., Guttormsen, A., Tell, G. et al. Implementation of nutritional guidelines in a university hospital monitored by repeated point prevalence surveys. Eur J Clin Nutr 66, 388–393 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2011.149

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2011.149

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Intervention-related, contextual and personal factors affecting the implementation of an evidence-based digital system for prevention and treatment of malnutrition in elderly institutionalized patients: a qualitative study

BMC Health Services Research (2023)

-

Comparison of nutritional risk screening with NRS2002 and the GLIM diagnostic criteria for malnutrition in hospitalized patients

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Evidence on nutritional therapy practice guidelines and implementation in adult critically ill patients: a scoping review protocol

Systematic Reviews (2019)

-

Changes in nutritional care after implementing national guidelines—a 10-year follow-up study

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2018)

-

Documentation and communication of nutritional care for elderly hospitalized patients: perspectives of nurses and undergraduate nurses in hospitals and nursing homes

BMC Nursing (2016)