“I first became intrigued by volcanoes as an undergraduate studying analytical chemistry in Yogyakarta, a city on the Indonesian island of Java. Yogyakarta lies in the shadow of Indonesia’s most famous volcano, Merapi. Every morning, I would see Merapi in the distance, a plume of ash rising from its crater. For my studies, I analysed the metal content of the surrounding volcanic soils.

After graduating, I spent ten years in oil and gas research, but in 2001 I returned to volcano research when I joined the Centre for Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation in Yogyakarta.

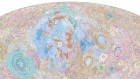

There, my colleagues and I monitor the activity of Indonesia’s volcanoes, and work towards hazard analysis and mitigation. This photograph was taken in September 2023 in the crater of Ijen volcano, in the east of Java. This crater contains the world’s largest acid lake. I’m holding a multiparameter analyser, which measures the acidity, temperature and conductivity of water, along with the total concentration of dissolved solids.

During that visit, I measured an extreme pH of 0.2 for Ijen’s lake. Its 36 million cubic metres of acidic water could be very dangerous to the surrounding population if there is an eruption. We monitor volcanic activity with geophysical devices such as seismometers, but also through the chemistry in the lake. When the activity changes, so does the chemical composition of the water — as well as its colour, which ranges from white to turquoise blue.

A few years ago, we would routinely visit Ijen to do tests and take samples. Now, we have installed automatic sensors that send results directly to our laboratory every 5 minutes. Because Indonesia has so many volcanoes, remote monitoring enables us to work much more efficiently than before. But sometimes I miss visiting a volcanic field as unique and beautiful as Ijen.”

‘Ash was falling like rain’: how I became a volcanologist

‘Ash was falling like rain’: how I became a volcanologist

Plumbing the depths of Costa Rica’s volcanoes

Plumbing the depths of Costa Rica’s volcanoes

The new science of volcanoes harnesses AI, satellites and gas sensors to forecast eruptions

The new science of volcanoes harnesses AI, satellites and gas sensors to forecast eruptions