In Unrooted, botanist Erin Zimmerman shares her struggle to balance research and family.Credit: Kenneth Wurdack

Unrooted: Botany, Motherhood, and the Fight to Save An Old Science Erin Zimmerman Melville House (2024)

Nineteenth-century English suffragist Lydia Ernestine Becker, a lifelong advocate for women’s right to vote, was also an accomplished botanist who discovered a peculiar hermaphrodite flower. She found that the female flowers of red campion, Lychnis diurna (now called Silene dioica), develop stamens — the pollen-producing male part of a flower — when infected with a fungus. She expounded on these ‘curious characteristics’ in correspondence with Charles Darwin, and published a paper on her findings in 1869 (L. Becker J. Bot. 7, 291–292; 1869).

“Becker’s research led her to consider that the seemingly fixed categories of male and female might not be as immutable as they first seemed,” notes evolutionary biologist Erin Zimmerman in her moving memoir of botany and motherhood, Unrooted. Becker concluded that girls and women were lagging behind only because they received less education than boys and men. Her ideas caused a backlash, and she was ridiculed by press critics — some even implied that she was a hermaphrodite herself.

Uncertainties in science and in life

In some ways, Becker’s story foreshadows that of Zimmerman. Women in science still struggle to succeed in academia in the face of ingrained sexism. In her book, Zimmerman describes her determination to pursue a career in her beloved field of botany. She travels from Montreal, Canada, to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, in London, and then to the Guyanese rainforest, in search of a group of tropical trees and shrubs known as Dialiinae (now called Dialioideae) — one of the earliest evolutionary branches of the legume family. In Guyana, she encounters an enormous anaconda and a terrier-size spotted rodent called a labba (Cuniculus paca). She climbs part-way up 60-metre-tall trees, battling her dread of falling as well as angry insects.

Perhaps Zimmerman’s most powerful fear, however, the difficulty of combining her career with motherhood. She tells her boyfriend Eric that she would “certainly not be having children”, and her concerns over parenthood are not unfounded. In the United States, 43% of women with full-time jobs in science leave the sector or take on part-time roles after having their first child (E. A. Cech and M. Blair-Loy Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 4182–4187; 2019). By contrast, only 23% of new fathers leave or reduce their hours.

The author experiences this herself, and she finds parallels between the obstacles faced by women in science and global threats to plants. According to the 2023 State of the World’s Plants and Fungi report (see go.nature.com/3xardd7), 45% of all known flowering plant species are at risk of extinction — a percentage eerily similar to that of women leaving full-time research.

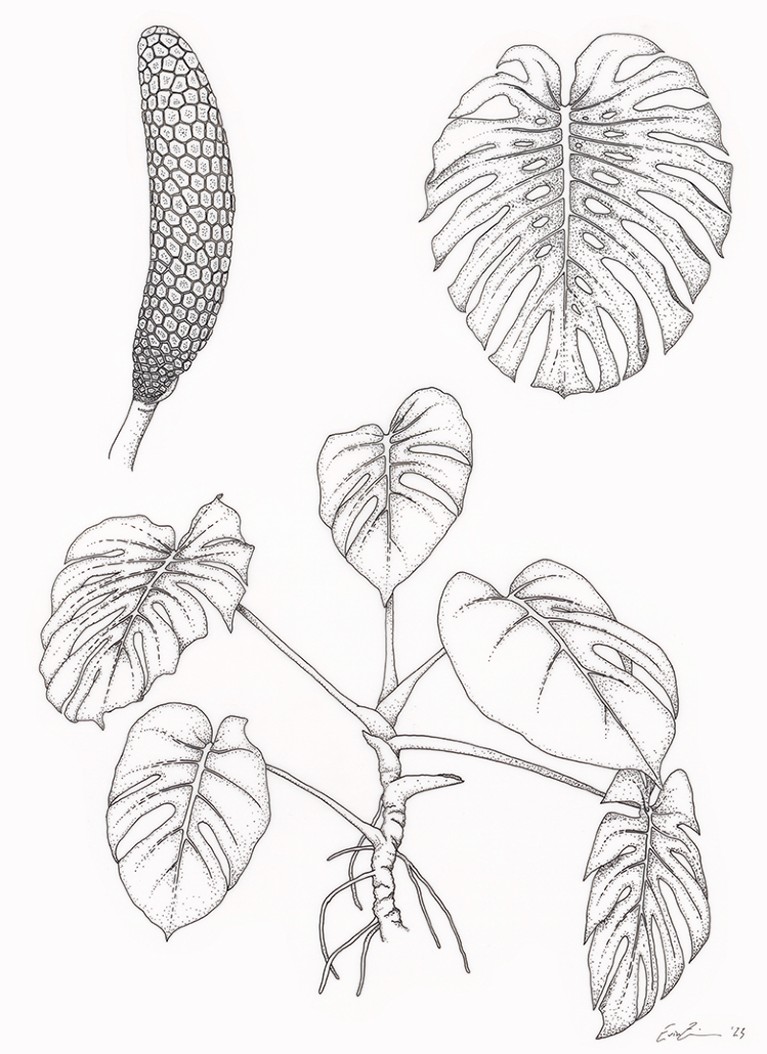

Zimmerman’s botanical sketches, such as this one of Monstera deliciosa, dot the book.Credit: Melville House Publishing

Zimmerman’s field is hardly secure: her PhD project involved carefully dissecting decades-old, dried plant specimens stored in herbaria and extracting DNA from the samples. These collections are important for assessing extinction risks, yet they are themselves under threat. “Old and venerable collections housing many priceless specimens look to some funding bodies like dusty old money pits,” she writes. In February, Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, announced the closure of its 100-year-old herbarium, which houses 825,000 specimens, saying that the collection had become “too expensive to maintain” (see go.nature.com/4cnbyjm).

Nevertheless, Zimmerman persisted. Her plants had become beloved children, absorbing her attention. Lists of specialized terms such as leaf shapes “read like an arcane spell book”: “Ovate. Lanceolate. Cordate. Falcate. Orbicular. Cuneate.” She draws plant specimens in meticulous detail, and these lovely illustrations dot the pages of her book.

But her devotion to her research becomes an obsession, isolating her. And as she plots her path, she realizes how tenuous her dream of tenure is: there are too few faculty positions.

A different future

Despite the pressures, Zimmerman manages to maintain a life outside the laboratory: soon after her doctoral defence — a moment she has dreamed of for years — she and Eric marry in the barn of her childhood home in Ontario. One month later, she discovers she is pregnant. In the middle of her pregnancy, she lands a postdoc position at a Canadian government agricultural facility.

How centuries of sexism excluded women from science — and how to redress the balance

This is where her personal and professional lives collide. Overworked, in pain, accused of having ‘brain fog’, dismissed for her concerns about working in a pesticide-sprayed greenhouse while pregnant and, later, longing for her infant daughter, Zimmerman decides to quit. She was appalled at her supervisor’s reaction: “he made it clear that he considered me to have been a terrible investment, and that he’d likely think twice the next time he interviewed a pregnant woman.”

This moment of misogyny leads Zimmerman to reconsider the landscape of science. Women are often derided for their reproductive choices, yet men have children, too. The highly praised Darwin, for example, had ten children with his cousin, Emma Wedgwood. Men who have become scientific heroes often dedicated all their waking hours to their research, while women — including their wives or, in the case of wealthy men, nannies — raised their children.

To slow “the haemorrhage of women” from the hyper-competitive world of research, we need better policies, Zimmerman writes. These should include protected parental leave, flexibility for new mothers to work from home, designated breast-pumping spaces (rather than the mildewed shower stall Zimmerman was forced to use) and childcare facilities at conferences, so that women don’t miss out on networking and hiring opportunities.

After departing from research, Zimmerman switched to science journalism, for which we should be grateful, for she writes beautifully. In some ways, her decision echoes Becker’s, who published her 1864 book Botany for Novices under just her initials (L.E.B.) and then left the field to dedicate herself to women’s activism. Now, 160 years later, Zimmerman can tell her story, under her full name. That’s progress.

Anna Atkins: pioneering botanical photographer who captured algae and ferns in ghostly blue images

Anna Atkins: pioneering botanical photographer who captured algae and ferns in ghostly blue images

How centuries of sexism excluded women from science — and how to redress the balance

How centuries of sexism excluded women from science — and how to redress the balance

Biodiversity loss and climate extremes — study the feedbacks

Biodiversity loss and climate extremes — study the feedbacks

Estella Bergere Leopold (1927–2024), passionate environmentalist who traced changing ecosystems

Estella Bergere Leopold (1927–2024), passionate environmentalist who traced changing ecosystems

Current conservation policies risk accelerating biodiversity loss

Current conservation policies risk accelerating biodiversity loss

Seeding an anti-racist culture at Scotland’s botanical gardens

Seeding an anti-racist culture at Scotland’s botanical gardens