Of the nearly two billion people living in countries that are holding elections this year, some have already cast their ballots. Elections held in Indonesia and Pakistan in February, among other countries, offer an early glimpse of what’s in store as artificial intelligence (AI) technologies steadily intrude into the electoral arena. The emerging picture is deeply worrying, and the concerns are much broader than just misinformation or the proliferation of fake news.

As the former director of the Machine Learning, Ethics, Transparency and Accountability (META) team at Twitter (before it became X), I can attest to the massive ongoing efforts to identify and halt election-related disinformation enabled by generative AI (GAI). But uses of AI by politicians and political parties for purposes that are not overtly malicious also raise deep ethical concerns.

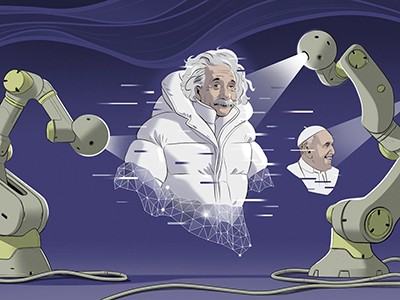

GAI is ushering in an era of ‘softfakes’. These are images, videos or audio clips that are doctored to make a political candidate seem more appealing. Whereas deepfakes (digitally altered visual media) and cheap fakes (low-quality altered media) are associated with malicious actors, softfakes are often made by the candidate’s campaign team itself.

How to stop AI deepfakes from sinking society — and science

In Indonesia’s presidential election, for example, winning candidate Prabowo Subianto relied heavily on GAI, creating and promoting cartoonish avatars to rebrand himself as gemoy, which means ‘cute and cuddly’. This AI-powered makeover was part of a broader attempt to appeal to younger voters and displace allegations linking him to human-rights abuses during his stint as a high-ranking army officer. The BBC dubbed him “Indonesia’s ‘cuddly grandpa’ with a bloody past”. Furthermore, clever use of deepfakes, including an AI ‘get out the vote’ virtual resurrection of Indonesia’s deceased former president Suharto by a group backing Subianto, is thought by some to have contributed to his surprising win.

Nighat Dad, the founder of the research and advocacy organization Digital Rights Foundation, based in Lahore, Pakistan, documented how candidates in Bangladesh and Pakistan used GAI in their campaigns, including AI-written articles penned under the candidate’s name. South and southeast Asian elections have been flooded with deepfake videos of candidates speaking in numerous languages, singing nostalgic songs and more — humanizing them in a way that the candidates themselves couldn’t do in reality.

What should be done? Global guidelines might be considered around the appropriate use of GAI in elections, but what should they be? There have already been some attempts. The US Federal Communications Commission, for instance, banned the use of AI-generated voices in phone calls, known as robocalls. Businesses such as Meta have launched watermarks — a label or embedded code added to an image or video — to flag manipulated media.

But these are blunt and often voluntary measures. Rules need to be put in place all along the communications pipeline — from the companies that generate AI content to the social-media platforms that distribute them.

What the EU’s tough AI law means for research and ChatGPT

Content-generation companies should take a closer look at defining how watermarks should be used. Watermarking can be as obvious as a stamp, or as complex as embedded metadata to be picked up by content distributors.

Companies that distribute content should put in place systems and resources to monitor not just misinformation, but also election-destabilizing softfakes that are released through official, candidate-endorsed channels. When candidates don’t adhere to watermarking — none of these practices are yet mandatory — social-media companies can flag and provide appropriate alerts to viewers. Media outlets can and should have clear policies on softfakes. They might, for example, allow a deepfake in which a victory speech is translated to multiple languages, but disallow deepfakes of deceased politicians supporting candidates.

Election regulatory and government bodies should closely examine the rise of companies that are engaging in the development of fake media. Text-to-speech and voice-emulation software from Eleven Labs, an AI company based in New York City, was deployed to generate robocalls that tried to dissuade voters from voting for US President Joe Biden in the New Hampshire primary elections in January, and to create the softfakes of former Pakistani prime minister Imran Khan during his 2024 campaign outreach from a prison cell. Rather than pass softfake regulation on companies, which could stifle allowable uses such as parody, I instead suggest establishing election standards on GAI use. There is a long history of laws that limit when, how and where candidates can campaign, and what they are allowed to say.

Citizens have a part to play as well. We all know that you cannot trust what you read on the Internet. Now, we must develop the reflexes to not only spot altered media, but also to avoid the emotional urge to think that candidates’ softfakes are ‘funny’ or ‘cute’. The intent of these isn’t to lie to you — they are often obviously AI generated. The goal is to make the candidate likeable.

Softfakes are already swaying elections in some of the largest democracies in the world. We would be wise to learn and adapt as the ongoing year of democracy, with some 70 elections, unfolds over the next few months.

What the EU’s tough AI law means for research and ChatGPT

What the EU’s tough AI law means for research and ChatGPT

Generative AI’s environmental costs are soaring — and mostly secret

Generative AI’s environmental costs are soaring — and mostly secret

Why open-source generative AI models are an ethical way forward for science

Why open-source generative AI models are an ethical way forward for science

How to stop AI deepfakes from sinking society — and science

How to stop AI deepfakes from sinking society — and science

Stop talking about tomorrow’s AI doomsday when AI poses risks today

Stop talking about tomorrow’s AI doomsday when AI poses risks today