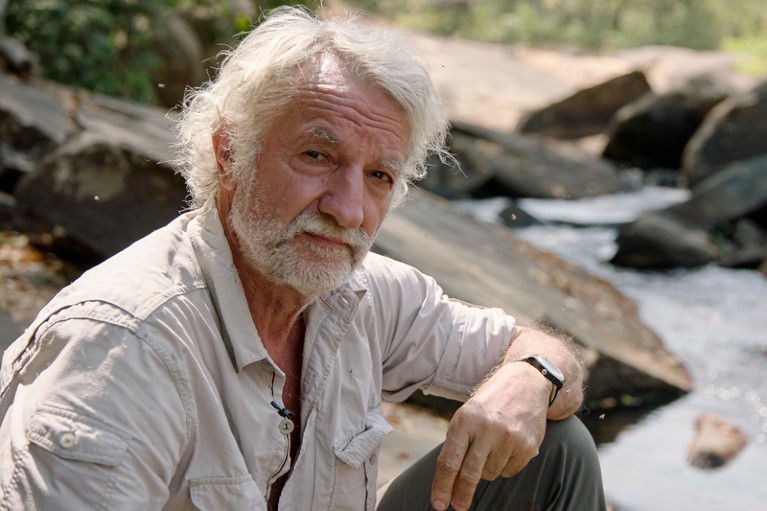

Credit: Matt Mays/Mays Entertainment

In 1979, ethologist Christophe Boesch and his wife Hedwige Boesch-Achermann began researching the behaviour of a community of wild West African chimpanzees in Taï National Park, Côte d’Ivoire. Their study became the first long-term research on chimpanzees to be conducted in a continuous rainforest, rather than in a mixed savannah habitat such as Gombe National Park, Tanzania, where primatologist Jane Goodall had been working for almost two decades. It led to numerous discoveries about cultural diversity and behavioural variation — revealing, for example, that chimpanzees used hammers to crack nuts, that males cared altruistically for unrelated orphans and how predation by leopards influenced grouping patterns. Boesch argued that, because the Taï population was relatively undisturbed, it yielded a uniquely informative picture of chimpanzee behavioural adaptations. The Taï project remains the only study of a large population of habituated West African chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus), a rapidly dwindling subspecies (taichimpproject.org). He has died aged 72.

Boesch promoted the conservation of chimpanzees by organizing population surveys, launching chimpanzee-research sites and driving the creation of national parks, including Moyen-Bafing National Park in Guinea. When faced with obstacles, from changing governments and obstructive mining companies to sceptical donor agencies, he had little patience for bureaucracy or unnecessary delays. He envisaged a continuous protected area that stretched from Senegal to Côte d’Ivoire and pursued this goal through the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation (WCF), which he and Boesch-Achermann co-founded in 2000. Under Boesch’s leadership, the WCF engaged local people and lobbied industries and ministries to avert threats from mining activities and infrastructural development. The foundation continues to lead conservation efforts in West Africa.

Boesch was born in St Gallen, Switzerland, in 1951. When he was 12 years old, his father, a professor of cultural psychology, gave him King Solomon’s Ring by ethologist Konrad Lorenz, a 1949 book that stimulated Boesch’s lifelong interest in animal behaviour. He attended secondary school in Paris and returned to Switzerland to study biology at the University of Geneva. His first experience of field work with great apes was in Rwanda, studying mountain gorillas as an assistant to US primatologist Dian Fossey.

Chimpanzees are dying from our colds — these scientists are trying to save them

After learning that chimpanzees in Taï use natural hammers to crack open edible nuts, the Boesches spent five years habituating a wild community there to their presence, much of the time in the field spent together with their two young children. At first, the chimpanzees invariably fled, so that for many years the research was, in Boesch’s words, “a study of chimpanzee behinds”. Persistence paid off and led to a PhD from the University of Zurich, Switzerland, in 1984 and to an assistant professorship at the University of Basel in 1991.

In 1997, Boesch became one of the founding directors of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. By then, research in Taï was producing rich data on three neighbouring communities, shedding light on intergroup dynamics and social traditions. In 1999, together with Andrew Whiten, Boesch organized a comparison of the behavioural diversity of seven chimpanzee populations. The resulting paper took the study of chimpanzee cultural variation to an increasingly systematic level and galvanized further work throughout Africa (A. Whiten et al. Nature 399, 682–685; 1999). Boesch set up an ambitious project to collect chimpanzee data from more than 50 sites in 18 countries. This project found evidence that chimpanzee cultural diversity had been reduced by human influences, suggesting that the conservation of these animals needs to include the protection of their local traditions.

These animals are racing towards extinction. A new home might be their last chance

Boesch thought that scientists routinely underestimated the cognitive complexity of chimpanzees, for example in their abilities to cooperate, teach their young or use several tool sets; and that studies of chimpanzees in captivity tended to have little relevance to understanding their behaviour in the wild. His pioneering findings often went against prevailing scientific thinking, but he trusted his eyes and never shied away from defending his views.

By the 1990s, chimpanzees in Taï were dying from pathogens, such as anthrax, Ebola and respiratory viruses, that decimated Boesch’s study community and endangered human observers. Boesch introduced safety measures and organized studies that led to the first direct evidence of viruses being transmitted from humans to wild apes.

In an era when painstaking fieldwork appealed less to students than did seemingly swifter rewards from laboratory experiments, Boesch insisted on the merits of old-fashioned patience: “Go to the field,” he would tell his students. “Observe the chimpanzees and don’t worry about the textbooks — the chimpanzees will teach you!”

His passion and enthusiasm for chimpanzee research and conservation were contagious. And Boesch inspired a generation of primatologists. Inza Koné, president of the African Primatological Society, referred to Boesch as the father of primatology in Côte d’Ivoire, a characterization that could fairly be extended to West Africa as a whole. Early in Boesch’s career, he realized that each chimpanzee population is unique and that connecting separate populations is the key to their survival. His more than four decades of devotion to studying and protecting wild chimpanzees leaves a lasting impact on their survival and our knowledge of this species.

Chimpanzees are dying from our colds — these scientists are trying to save them

Chimpanzees are dying from our colds — these scientists are trying to save them

These animals are racing towards extinction. A new home might be their last chance

These animals are racing towards extinction. A new home might be their last chance

How wild monkeys ‘laundered’ for science could undermine research

How wild monkeys ‘laundered’ for science could undermine research

Menopausal chimpanzees deepen the mystery of why women stop reproducing

Menopausal chimpanzees deepen the mystery of why women stop reproducing

Biggest ever study of primate genomes has surprises for humanity

Biggest ever study of primate genomes has surprises for humanity