Download the Nature Podcast 10 January 2024

In this episode of the Nature Podcast, we catch up on some science stories from the holiday period by diving into the Nature Briefing.

We chat about: an extra-warm sweater inspired by polar bear fur; the fossil find revealing what a juvenile tyrannosaur liked to snack on; why scientists are struggling to open OSIRIS-REx’s sample container; how 2023 was a record for retractions; and how cats like to play fetch, sometimes.

Nature News: Polar bear fur-inspired sweater is thinner than a down jacket — and just as warm

Scientific American: Tyrannosaur’s Stomach Contents Have Been Found for the First Time

Nature News: ‘Head-scratcher’: first look at asteroid dust brought to Earth offers surprises

Nature News: More than 10,000 research papers were retracted in 2023 — a new record

Scientific American: Cats Play Fetch, Too—But Only on Their Own Terms

Never miss an episode. Subscribe to the Nature Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast app. An RSS feed for the Nature Podcast is available too.

TRANSCRIPT

Benjamin Thompson

Hi listeners, Benjamin from the Nature Podcast here. As we sort of feel our way blinkingly into 2024, we're going to open with a few stories you might have missed from the Briefing over the past few weeks. And this is the third year we've done this, I think this is now sort of a tradition. And joining me to do so are Noah Baker, Noah how are you doing today?

Noah Baker

I'm doing very well. Happy New Year to everyone.

Benjamin Thompson

And Flora Graham from the Nature Briefing. Flora, hi.

Flora Graham

Hi, Happy New Year.

Benjamin Thompson

Well, as I say, few stories to cover this week. Noah, why don't you go first, what have you got to bring to the show?

Noah Baker

I feel like it's a new year and I didn't want to start with heavy, deep stories. And so, I've gone for a jumper that has been designed to mimic polar bear fur.

Benjamin Thompson

Right, I’m guessing polar bears, pretty good at living in quite cold places. So, I imagine that this new jumper maybe offers some advances over previous jumper technology, if that's the right way to describe it.

Noah Baker

Absolutely. So, jumper or sweater for people that may not be familiar with our British vernacular, this isn't really about the jumper so much as it is actually about the fibre. So, this is research that was published in Science and I was reading about it in Nature. So many clothing manufacturers want to make really insulating fibres for lots of obvious reasons. But it's been quite difficult to do that with anything apart from natural fibres. Evolution is really the winner in many cases here. So things like down, things like wool are really, really high-performing. And that's because things like polar bears needed to have very insulating fur and evolution doth provide. Now, that doesn't mean that there aren't incredibly insulating materials that exist. So, aerogels for example, one of the most insulating materials in the world in fact potentially the most insulating material in the world, which are used for things like space exploration, or things like building insulation. These are these incredibly low-density, high-insulating materials. They work really, really well but the problem is that they aren't very flexible, and they also tend to lose their efficacy when you make them wet. So they're pretty rubbish when it comes to trying to make clothing. However, some researchers have now done what researchers like to do, which is do the bioinspiration thing, looked at polar bear fur and tried to find a way to take inspiration from polar bear fur to create aerogel fibres. And that is very much what they've done here.

Benjamin Thompson

I mean, we've covered aerogels in the podcast before, right? And I've seen people lifting blocks of them up with their little fingers. So they are super light and as you say they've got incredible insulation properties. But if I'm out for a walk in Cumbria — as I did over the last few weeks — it was absolutely sheeting down with rain. A solid, rigid block of aerogel ain't cutting it. So how have they gone about sort of de-blocking it I guess, turning it into a thread?

Noah Baker

Yeah, totally. So that lightness is because aerogels are filled with air, as you might imagine, or gas. And that porous property is what prevents conduction of heat and makes them such great insulators. And if you look at a cross-section under a microscope of a polar bear hair, what you'll see is this porous centre, this porous core, which gives that thermal insulation, but then it's wrapped in a tough and flexible outer layer. And that provides both insulation and the flexibility and the strength and the toughness that you need for a hair. And so that's what the researchers tried to do here, they took an aerogel core and then they wrapped it with a common thermoplastic called polyurethane which is used often in clothing. They did it using a technique called ‘freeze-spinning’, which is essentially squeezing a solution through a syringe and freezing it as it goes. It's more complicated than I’ve made it sound there, but that's the gist of it. And they've created this thermoplastic coated aerogel centre, which very much mimics a polar bear hair. And then they've used this to try to create garments. Now what's most important is they've tested the fibre and found out that you can stretch it and put it under immense strain and it maintains its properties. In fact, you can stretch it to double its length 10,000 times and it still keeps insulating, you can also make it wet. And they did indeed make a garment out of it, a jumper, a sweater and they put it on a person and they took the temperature down to minus 20 degrees centigrade and they measured the outer temperature of the garment as a way of assessing how much heat it was leaking, I suppose, how well it was insulating, and then they compared that to various other things. So, for example, they compared to wool or to cotton, or to the gold standard, which is down. Now down was a thick jacket, five times thicker than the aerogel garment but actually was slightly less insulating overall than the aerogel was and so you have this very thin, very high-insulating garment that can protect people from getting cold better than down which is currently one of the most commonly used materials for this high insulation purpose.

Flora Graham

Okay, so at the risk of sounding shallow, how does it look? Is it like a banging polar bear white fur puffer because that's really what I would like.

Noah Baker

You know, I kind of wish it was, but it's actually like a really plain, I think kind of on-trend, it vaguely looks crocheted but it is sort of white slash off-white, which I think is very on brand for polar bear, you can sort of get a polar bear inspiration from it. But it's really quite a simple garment. I couldn't tell from the story from the paper, it says that it was made by one of the research team. In my head, I really hope that one of the research team just personally knitted it, it actually has a nice bit of like decoration around the V-neck. I think that would be lovely.

Flora Graham

I think if I was wearing that I would be having to drop that, you know, did you–did I mention this is actually polar bear inspired not just any white jumper.

Benjamin Thompson

Oatmeal, I think is the on-trend colour at the moment, isn't it? I think as someone who has worn an oatmeal jumper covered in a down coat covered in technical fabric, this honestly sounds fantastic. Like, I mean, is this gonna be available in the shops anytime soon?

Noah Baker

Sadly, no. So the freeze-spinning technique that they use to create the fibre is nothing that's going to be scalable for the kinds of scale that you would need to create clothing on any kind of reasonable budget. But it is a concept that could potentially be moved forwards. And so there is hopes that this kind of material might be able to be used in the future, but we aren't going to be getting polar bear jackets anytime soon.

Flora Graham

So maybe it's like a NASA astronaut or somebody who's willing to spend billions on some key temperature garment, and then they whip off their suit and it's like Chris Evans in Glass Onion, with like the iconic oatmeal jumper on underneath.

Noah Baker

Absolutely. I mean, so that is definitely, probably the first uses that are gunna to get this for sure is people like NASA, these places where there is super high-efficiency, and money is not really any object. That's where we're likely to see these kinds of technologies being used first. But there is a lot of arguments that sports people, for example, could really benefit from this. And so, you never know where the markets lie, where the costto-benefit ratio will lie. So we'll have to keep watching it to see when we get polar bear jumpers in the future. I should clarify, not made from polar bear.

Benjamin Thompson

I mean, that's a fantastic story. And I can genuinely see the benefit of that. I'll go next, I think, and I've got a story that I read about in Scientific American. And it's a neat one, actually, it's direct proof of what a tyrannosaur ate, I managed to do a dinosaur story or an extinct animal story every time we've done this, and this is no different. And it was published in the journal Scientific Advances. And it's an interesting one because it kind of gives an insight into both the diet and maybe sort of place in the broader ecosystem that this dinosaur might have, which have only really been hypothesised in the past.

Noah Baker

I feel like it has been hypothesised, but I feel like I've heard 1,000 different versions of how tyrannosaurs lived: were they scavengers, were they hunters, were they predators? And I'm very interested to find out what the latest step in this saga is of what does a Tyrannosaurus eat?

Benjamin Thompson

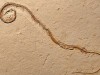

Well, I will say this isn't the tyrannosaur that you're maybe thinking of right? This isn't Tyrannosaurus rex, this is Gorgosaurus libratus, right, which is a type of tyrannosaurid and part of the family that includes their famous cousin. Now this species lived in the late Cretaceous Period, maybe 80 million years ago, so several million years earlier than T. rex. Okay, and when it was fully grown, it was a unit I won't lie here, you know, taller than a giraffe weighed as much as an elephant, a massive apex predator. But in this case, this research is looking at a juvenile. So, a juvenile of the species was found encased in rock in Alberta, Canada, and very gently extracted. And what's neat here is the researchers were looking at this kind of fossil and going, ‘oh, hang on, there's too many legs here, this dinosaur has got too many legs’. And it turned out that inside this juvenile tyrannosaur’s stomach, were two sets of legs from another sort of dinosaur — oviraptorosaurs. Okay, and these are small dinosaurs, feathered with a toothless beak. And this is a very rare find, indeed.

Noah Baker

I love that the bit they found was legs. I mean, we hear a lot in ecology and modern ecology of finding stomach contents and being able to work out what things ate by looking at the stomach contents of an animal that has died, but it must be much rarer to be able to find fossilized remains of an identifiable animal inside a fossil — that's pretty exciting.

Benjamin Thompson

And what's more is the fact that the chances of it happening are so small, right? So finding the stomach contents means that the dinosaur must have kind of had its dinner, then died quite shortly afterwards, then been covered up. So the odds of that are absolutely astronomical, I think. And before this, researchers really only sort of had a guess at what tyrannosaurs might have eaten by looking, you know, at their skull shape, looking at bite marks on these megaherbivores, these giant herbivores and looking at fossilized poo. And I think previous work has really suggested a lot of pulverized bone, but in this case, we've got some very quite well defined legs and apparently, you know, being in the stomach actually protected them.

Flora Graham

So, does that mean that the tyrannosaur swallowed them whole then?

Benjamin Thompson

It seems to be that that was the case, it seems to have bitten off the legs and left the body. So, the stuff that people can learn from fossils, I think consistently blows my mind. So these two oviraptorosaurs were eaten individually, the bodies were seemingly left behind just the legs were eaten, and they were maybe a year or two old and the juvenile was probably six or seven years old. But what is interesting here is these two dinosaurs were eaten at different times, the stomach-acid etchings suggested that these weren't eaten in one go. So, maybe this is giving an insight into the fact that these dinosaurs were like sort of top of the menu for this juvenile dinosaur.

Flora Graham

It's amazing. It really gives you such a mental film of how this giant predator must have been living and running around biting the legs off chickens.

Noah Baker

I was gonna say I feel like it's weird to just eat the legs. But then I thought, well, we just eat the legs of chickens all the time. But I assume that probably this dinosaur wasn’t doing a lovely, you know, buttermilk batter on their legs, but still fascinating.

Benjamin Thompson

And more inferences can be made from this because I think what this shows is that the lifestyle or the diet of this juvenile seems to be quite different from the adult Gorgosaurus. Okay, so, the juvenile has these kind of blade-like teeth, and it seems to be — from this research — taking on smaller dinosaurs, right, eating parts of them just wolfing them down. Whereas the adults were this huge apex predator, and they've got very different teeth, which I've seen described as ‘killer bananas’. Okay, and these are quite good at kind of scraping and crunching through bone and potentially taking on these megaherbivores. And so there seems to be this shift in diet, which is seen in some things like crocodiles, and potentially this, this lifestyle change might help explain why tyrannosaurs, you know, lasted for quite such a long time evolutionary, right, they could fit in different niches. But as it's often the way with these sorts of things, that's kind of debatable because they found a dinosaur that seems to have changed its lifestyle. That doesn't mean that you know, all dinosaurs didn't do that. This is just n=1 yet, and it throws more questions about the lifestyle of these carnivores.

Noah Baker

Absolutely.

Flora Graham

Maybe it was just a picky eater. I mean, it was a juvenile. I know a lot of parents can sympathise with that kid that's like, all I will eat is oviraptor legs and I refuse to eat anything else.

Benjamin Thompson

Well, let's keep going on this sort of little roundup of stories. Flora, you're gonna go up next, I think, what have you got? What have you brought to the table today?

Flora Graham

Well, you know, I've been on tenterhooks since the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft first approached the asteroid Bennu, way back in September, and I was delighted to see that it successfully smashed in there grabbed a bunch of asteroid, material dust and particles in its sample collector, and successfully came back to Earth and kind of in a running orbit passed our planet, dropped the sample container, which people then successfully found, brought it back to NASA, put it into its specially constructed sealed container so that it would not be contaminated with any of the gases from Earth or any particles from Earth. And they would have special tools already inside to open it up, and then they couldn't get it open–

Benjamin Thompson

–oh, no–

Flora Graham

–I mean, it's just such an amazing story. I mean, there's no bad news here. Because the sample collection was so successful, even the dust and material on the outside of the container — which was still completely separate, we definitely know this isn't just like dirt that it landed in or anything — there was so much material just stuck around the outside of the lid that it's already far exceeded the amount that they had hoped to collect. So, they've already got more than 70 grams, which is one researcher on the team said, you know, this is going to keep us busy for years. That being said, you know, understandably, they're quite keen to get inside. But you can't just open up this special enclosure and you know, whack it on the side like you would a tin that's got the lid stuck to get the pickles out. You have to think about what would fit inside there? How can you get it in without contamination? So they've carefully use tweezers to remove what they could. I think it was two bolts, possibly that were sticking. So they have actually manufactured a special additional tool that will fit inside this enclosure in order to go at it. So there's not been any announcement yet they finally got through. But I must give a shout out to all the Briefing readers who emailed me with suggestions of how to open a stuck bolt, some absolute classics, I mean, you know, my go-to, which is of course, run the lid under hot water is not a goer on this one. But apparently some engineers have written me to tell me that a key issue in engineering is often that if a system is vibrating, the bolts and screws and nuts will actually unscrew themselves. So this is apparently something that has to be constantly considered and factored into your design. So there was some question of like, could we vibrate it in a way that would cause it to loosen and stuff? So yeah, you know, NASA, get in touch we've got some great suggestions for you in the Briefing inbox.

Benjamin Thompson

I will say that I'm with the school of DIY thought that you only need two tools: a hammer and duct tape. And if it doesn't move and it should, hit it as hard as you can with a hammer. If it does move and it shouldn't, stick it down with duct tape. Can I be an asset to NASA in any way do you think?

Flora Graham

I mean, I think yeah, if they just wrapped it in duct tape, you know I think the key to that is you would need somebody on the spacecraft ideally, once the sample was taken, to just quickly wrap that up with some duct tape. But of course, everything's a little bit more complicated when it comes to outer space. Actually, NASA just recently released some news explaining why the spacecraft actually did maybe hit Bennu a little harder than they had planned, which was one of the many parachute systems that was designed to slowly bring it down to kind of do its little fist bump with the asteroid, did not fire as planned. And you know, NASA, we know this from the Challenger disaster. One thing they do do is, you know, very deep investigation when things go wrong. And in this case, what they said was, they think that maybe the wiring diagram for the parachutes was not quite clear, and could have caused the engineers to wire it incorrectly. And luckily, the main parachute, the big parachute, was strong enough to slow the spacecraft and everything, you know, proceeded to plan so it was certainly wasn't a deal breaker. You know, what's really fun is that the spacecraft is still going, it hasn't come back to Earth, it just dropped off its payload, and it's headed to another asteroid. So we'll get some more information from its next visit, not a sample, but some more information from an asteroid with a different makeup of materials we think.

Noah Baker

I find these missions always fascinating because of just the engineering feat of it all. And I think you could say, oh, let's just pop up to an asteroid, grab a bit of dirt and come back down again, like, sure that sounds simple. But the level of invention that is needed to do this, even to the point that they needed to invent a brand-new tool just to undo a stuck bolt. I mean, there's no off the shelf elements to any of these stories, because that's so complicated to do such a huge task. Fascinating to watch I mean, I'm sure engineers reading the Briefing are as gripped I mean, I'm not an engineer, and I'm gripped by it.

Flora Graham

I mean, what's really constantly amazing for me when I write about this story is it's not even the first sample that we've had back from an asteroid. You know, there was the Japanese mission, the Hayabusa, which brought back a much, much tinier sample. What's one of the things that's very exciting about this one is the volume of material that they’ve brought back. But the idea that this isn't even the first, it's really just so exciting. And I can't imagine how it must feel to be, you know, one of the researchers and engineers working on the project and seeing something like that come to fruition must be just incredibly fulfilling.

Noah Baker

And they have gathered around 70 grams from the outside, and we're waiting to find out when the opening is going to happen. Are we just literally waiting to find out when the opening happens? Is there a date? Are there any rumours about when we find out what's inside the capsule?

Flora Graham

As far as I can tell, the latest update is we're still working on it. So yeah, I'll definitely I'll be the first one to let you know through the Briefing when what comes out. And who knows, you know, it’d be great to see just some legs just an oviraptor.

Noah Baker

Just some oviraptor legs. Exactly, that's what I hope to find in there.

Benjamin Thompson

And a nice email to me saying, “thanks, Ben, you were absolutely on the money. You just needed a bigger hammer.” Right, let's move on. Why don't I go next again, and this story couldn't be more different. And we like to talk about records being broken. And this is a record that isn't ideal, to be honest with you. This is a story I read about in Nature and it's about the number of retractions issued for research articles in 2023. So last year, and it passed 10,000 so it’s smashing previous records.

Noah Baker

Obviously, keeping a track on the number of retractions is a very important thing to do when you're trying to look at the reproducibility of science, the quality of the research that's being done. Also trying to investigate the publishing process that's also an important element to this, looking at peer review. I think it might be worth just starting with assessing some of the reasons that papers get retracted in the first place.

Benjamin Thompson

Well, there's a few factors for why papers might get retracted it’s a combination of things. I mean, there are of course, genuine retractions, when researchers notice errors in their work and say, look, this isn't quite right, we need to retract this paper. They, I have to say are in the minority in this case. So the majority of retractions are due to sham papers and peer review fraud. Okay. And in this article in Nature, there's been an analysis of what's been going on and it seems like the bulk of 2023 retractions were from journals owned by Hindawi. Now this is a London-based subsidiary of the publisher Wiley. Now so far this year Hindawi journals have pulled more than 8,000 articles, okay, citing factors such as, quote “concerns that the peer review process has been compromised” un-quote and quote “systematic manipulation of the publication and peer review process” un-quote, and this was uncovered by investigations from internal editors, and research-integrity sleuths who raised questions about these articles that just had incoherent text or irrelevant references. And most of these Hindawi retractions were from special issues. Okay, and I'm sure our listeners are familiar with these. But these are collections of articles, you know, on a particular area, overseen by guest editors. And special issues in general are notorious for being exploited by scammers. People can pose as researchers and say I'll be an editor and then just use it to publish low quality or sham papers. And I think there's been a big knock-on here for Hindawi as well. On the 6th of December, Wiley announced in an earnings call that it would stop using the Hindawi brand name altogether, and it would fold existing journals into its own brand and they're expected to lose a significant amount of revenue. And the article quotes a Wiley spokesperson who says that they're anticipating further retractions, but didn't say how many. Also that special issues continue to play a valuable role in serving the research community. And that they put in place more rigorous processes to confirm the identity of guest editors and oversee manuscripts, removing hundreds of bad actors and so on.

Noah Baker

I have to say that this increase in this kind of retraction is something that has been brought to my attention more and more over the last few years. But that also means that there's more and more awareness of this kind of publication. And yet the numbers are still going up, it feels a little bit like a kind of an arms-race between the people that are trying to exploit the problems and the people that are trying to catch the problems. And the number of retracted articles this year is almost double what it was last year. I mean, this is rising quickly. And researchers think this may not be all of it, right?

Benjamin Thompson

Oh, 100% I mean, there's two points there and I think they're both interesting ones. Nature's analysis suggests that the retraction rate for papers — which is the proportion of papers in any given year that get retracted — has more than trebled in the last decade. And in 2022, it exceeded 0.2%, which doesn't seem like a lot but when you think about the number of papers published each year, that is a huge amount. And in fact, this retraction level is rising at a rate that outstrips the growth in scientific papers. And these papers get cited a lot before they get kind of found out and retracted. But you raised the point that there must be a lot and I think integrity sleuths are saying that really this is potentially the tip of the iceberg. 50,000 papers in total have been retracted but the number of paper mills that exist – and these are these businesses that sell bogus research papers, or authorships – they're estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands of papers, these things have published. So there must be so many more to find out. And of course, there are genuine papers to get retracted as well. But as I say, that's a much smaller percentage overall.

Flora Graham

I mean, the number of retractions is certainly shocking and definitely casts a pall over scientific publishing in general. But I think we have to remember that this is really the immune system of scientific publishing. You know, this is a symptom of the real sickness that's underneath, it's a topic we cover, often in Nature, the pressure to publish, the extreme pressure to put out papers. And often we hear from scientists, especially in low- and middle-income countries that are drawn into these paper mills not always with the worst of intentions, because they don't have the resources to do otherwise. And I think another thing worth looking at is the fact that this immune system of retractions often is being powered by volunteers. A lot of these research-integrity sleuths are doing this, on their own time, often putting themselves really out there on a limb. You know, Elizabeth Bik, who won Nature’s co-sponsored John Maddox award for bravery in the scientific field is one of those who has been subjected to a lot of lawsuits and a lot of abuse for her work exposing scientific fraud. And something like Retraction Watch, which, you know, really grew from a small group putting together a blog kind of shedding light on some of the most egregious scientific fraud that's going on out there in publishing. And they really created something special with their database, which was the foundation of the Nature analysis, and tracking these retractions. And it's great to see that they've entered a partnership with CrossRef, in 2023, to really solidify the work that they're doing. Because I think we lean so much on these volunteers it's no wonder it's only the tip of the iceberg, because I think that as you say, the arms race is very one sided. Because you know, we certainly do not have these huge profit-making enterprises investing in retraction tracking and things as much as we have the kind of perverse incentives that cause these papers to be turned out in their hundreds of thousands.

Noah Baker

Absolutely, you create a system where you publish-or-perish, and people will find ways to publish, and especially when they are resource limited, and there are no other options for them then it's a right place for bad actors to arrive and create all of these problems. And so, it seems so unsurprising and yet, it's happening. And it's not being tackled brilliantly yet, as you say, because there isn’t a resource behind the trying to prevent these kinds of things from happening. But maybe moving forward with these kinds of new collaborations, like the collaboration between Retraction Watch and CrossRef we might see something changing in the coming months, years, who knows, it's certainly something that we're going to have to watch very closely as a publisher and as a magazine.

Benjamin Thompson

And at this point, obviously we have to say the Nature news is editorially-independent of the journal. Listen, let's bring it home. And who better to do so than Noah Baker. Noah, let's have one more story then for this little roundup of Briefing stories. What have you got?

Noah Baker

Look usually when we do these, I try to choose a kind of an important story or a chewy story or a story that's really gets to the heart of what we as science journalists really care about. But I think maybe I'm tired in 2024. So I've got a story about cats fetching things.

Benjamin Thompson

Well known for their capability and want to go and get things and bring things back, cats, of course.

Noah Baker

So actually, this grabbed me because my cat Slightly he is a fetcher and he has fetched since he was a very small little kitten. And I also have a dog now called Isla, and she loves fetch beyond all things. And I was fascinated because there is some research that is now being done about cats propensity to fetch. Are either of you pet owners?

Benjamin Thompson

I sometimes look after some cats, shout out to Mickey and Gavin, neither of whom are fetchers. I think I’ve thrown something for Gavin and he’s just looked at me like, what are you doing human, and just going about his merry way.

Flora Graham

Sadly, I inherited a horrific cat allergy. Yeah, I love them from afar.

Noah Baker

That's a pretty solid reason. So, as you say, Ben, cats aren't known for their fetching ability. But in a big survey that was done by some researchers at British universities have put out this survey through social media asking for information about people who have cats that fetch and they wanted to work out whether on this behaviour was something that's being trained into them, because they knew that on occasion, it does seem to happen. And they got around 1,000 responses, mostly from mixed breed owners, but some from purebred owners. And they found that of these cats, which we should say all did fetch, that was one of the requirements of the survey, they found out that in the vast majority of cases, 94.4% of cases, in fact, these cats were not taught to fetch, they just started doing it on their own. They were keen to fetch, it seems to be something that cats like to do, or certainly the cats involved in this survey do. But what's interesting is that the researchers think there’s a differentiation with dogs here, dogs, it’s believed, the propensity to fetch was bred into dogs, retrievers, for example, were very much bred to retrieve that is one of their sort of functions as a working dog. However, these cats, they do it on their own terms and most of the people who have cats in this survey that fetch said that it started because they dropped something, and their cat picked it up. And they were, oh, that's odd, or their cat brought them a toy, and then they just discarded it and a cat brought it back to them again and that started this cycle of fetch. And they realised that was a game that they could play with cats, because cats like to play and cats like to play fetch, but they don't like to be trained to do it, they just like to do it on their own terms, which seems, you know, very appropriate for what it is that I know about cats.

My cat Slightly that fetches, he just used to bring me things, and I used to throw them away, and he bring them back, that was exactly how it started for me. I didn't sit down and try to give him treats if he brought me anything back, there was no training involved. And I think this is a fascinating insight, as a cat owner, and a dog owner into the nature of play. But I also think it's really lovely when science aligns with our kind of subjective experience of animals, and that these cats like to do things on their own terms, and they won't do it unless they want it, whereas a dog will do it, because they just want to please or they're just so focused on it all the time. Whereas a cats like no, I'll do it if I wanna I’m not going to do it otherwise.

Flora Graham

So I don't have cats, but I have kids, and I'm like any creature, you know, of that level of intelligence,so I'm thinking like toddlers, cats, dog, you know, maybe I’d throw something fun that they like they'll go get it. I guess, one of the kind of threads that runs through a lot of animal-behaviour research, having read so much of it in my career is that you know, animals are just complex, cool creatures. And that is at many, many different branches of the evolutionary tree. And I guess it's not that I'm not delighted by this research. But it's the fact that for me, I'm no longer surprised when animals display behaviour that I consider playful, emotionally complex, and kind of reflecting their own individual experiences and seeking stimulus that's not just like a robotic pursuit of eating and sleeping.

Noah Baker

Absolutely. I mean, I think it should be said that there's lots of evidence across lots of different animals from lots of different taxon that play is an important element of their development. I mean, there's research into children and the value of free play in the development of children and that's very clear. But there's behaviour that’s been shown in mice, in cats, in dogs, in dolphins, in elephants. I mean, this is an element of their development, as well. And as you say, it isn't particularly surprising. I think it's maybe the word you used again is the right word for me – it's delightful, rather than surprising. I think it's wonderful to see this kind of study. And we should say, this is 1,000 pre-selected animals through a survey it's not a double-blind trial of all cats in the world. But it is wonderful when these kinds of data support things that we're interested in. And the researchers say this, you know, indicates that people should think about play with their cats or think about fetch as a thing they might want to do. Pay attention if your cats bring you something, maybe they want to fetch, that seems to be something they might want to do. And that might be good for the development or well-being of your cat.

Benjamin Thompson

Now you've introduced an element of hope, Noah. When I throw something for Gavin, he might bring it back. I don't know. He's not going to bring it back is he. Anyway, let's leave it there. Some absolutely wonderful stories. Thank you both so much for joining me. We'll be doing the same thing again next year I have no doubt. But listeners, we'll be back next week with a regular edition of the Nature Podcast bringing you the latest news from the wide world of science. To learn more about the stories we talked about in this episode, and a way you can sign up for the Nature Briefing, look for links in the show notes. But until next time, all this left to do is to say Noah and Flora, thank you so much for joining me today.

Flora Graham

Thank you very much.

Noah Baker

Thanks, Ben.

Nanomaterials pave the way for the next computing generation

Nanomaterials pave the way for the next computing generation

Polar bear researchers struggle for air time

Polar bear researchers struggle for air time

Prized dinosaur fossil will finally be returned to Brazil

Prized dinosaur fossil will finally be returned to Brazil

Massive study of pet dogs shows breed does not predict behaviour

Massive study of pet dogs shows breed does not predict behaviour

Polar bear population discovered that can survive with little sea ice

Polar bear population discovered that can survive with little sea ice

Four-legged fossil snake is a world first

Four-legged fossil snake is a world first

‘Incredible’ asteroid sample ferried to Earth is rich in the building blocks of life

‘Incredible’ asteroid sample ferried to Earth is rich in the building blocks of life