Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in October 2022, after winning a bruising election campaign.Credit: Nelson Almeida/AFP via Getty

In August 2022, Luiz Eduardo Del-Bem packed his bags for his second long research trip to the United States, leaving his home in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. He planned to spend a year doing a visiting professorship at Michigan State University in East Lansing. Almost a decade earlier, the evolutionary biologist had spent two years doing postdoctoral research at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts. But the 2022 trip felt very different from his previous one. He was worried about the twists and turns Brazilian science was taking and that he might need to make plans to continue his career elsewhere.

“I didn’t know whether my wife and I would be back to Brazil or not — at least in the foreseeable future. I considered applying for a permanent position in Michigan,” he says. While doing his visiting professorship, Del-Bem planned to halt his laboratory activity at the Federal University of Minas Gerais in Belo Horizonte, where he’s worked as a professor since 2018, but continue to teach classes remotely and mentor his students back in Brazil. “I was quite worried that changes in the Brazilian academic system would bring it to a complete collapse. I feared that another four years [of a Jair Bolsonaro government] could mean my profession wouldn’t even exist any more in Brazil,” he says.

Politics and the environment collide in Brazil: Lula’s first year back in office

Del-Bem’s anxiety stemmed, he says, from the damaging effects of several budget cuts and the hostile environment Bolsonaro’s government had created towards science. “There was persecution of scientific research, academia and professors, a sensation many colleagues and I shared,” he says.

Soon after he was elected in 2019, Bolsonaro accused scientists of distorting deforestation data and fired Ricardo Galvão, director of the National Institute for Space Research (INPE), after he backed his agency’s findings that deforestation in the Amazon was increasing and clashed with the president publicly. In 2021, Bolsonaro revoked the National Order of Scientific Merit honours of two researchers: Marcus Vinícius Guimarães de Lacerda, from the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Rio de Janeiro, and Adele Benzaken, former director of the HIV/AIDS department of Brazil’s Ministry of Health. Lacerda had led some of the first studies showing that the drug chloroquine did not work in the treatment of COVID-19, and Benzaken had worked on a booklet about sexually transmitted diseases that was aimed at transexual men. In protest to the revocations, 21 other scientists refused their honours.

Del-Bem was a vocal opposer of the government on social media and faced online hate, including receiving a few threats from users using false profiles.

But just two months after Del-Bem and his wife arrived in the United States, Brazil elected to replace Bolsonaro with left-wing candidate Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (widely known as Lula).

“I’ll never forget that day,” Del-Bem says. “A few seconds after the result, we popped champagne that had been in the fridge for months and started to make plans to go back to Brazil,” he recalls. “I felt we would be able to go back safely and move on with our lives.”

Slow progress

The atmosphere has changed significantly since the start of Lula’s presidential term, his third after his second term ended in 2010. But challenges remain, according to Del-Bem. “In my lab, I cannot turn the air conditioning on because my department doesn’t have the funds to fix it. Practical classes are difficult because most of the microscopes are broken or need maintenance,” he says. “There are clear signs of hope that we did not have under Bolsonaro, but we have not seen many structural changes in this first year of the Lula government,” he adds.

Other scientists paint a similar picture, pointing to rooms and laboratories in universities that have fallen into disrepair, and unfavourable currency exchange rates that make open-access article processing charges and equipment purchases prohibitively expensive.

Air of hope

Thiago Gonçalves, an astronomer at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, has also noticed a change in tone under Lula’s government. “I follow [science minister] Luciana Santos on social media, and it’s a great relief to see how she addresses science and the use of scientific evidence to back policy — we see there’s a disposition to include scientists in the public debate at large,” he says. Graduate grants have risen by about 40%, he adds, an encouraging sign for master’s and doctoral students.

However, substantial change will demand a lot more work, Gonçalves says. Grant funding for individual researchers does not cover much-needed repairs and maintenance to university buildings, for instance. “At our department, we have a room that has been taken over by mould and is currently not in use,” he says. “I hope we will be able to restore it before the next semester begins.”

Over the past decade, the budget for federal universities has nosedived. According to the Knowledge Observatory, a network of associations and unions of university professors across the country, the budget for investment and maintenance in 2023 (about 7 billion reais, or US$1.44 billion) was less than half that for 2014, when this type of investment peaked at 15.5 billion reais. The budget for 2024 continues that pattern, projected at 6.8 billion reais.

More funding for advanced infrastructure projects should help researchers to replace Brazil’s defunct UVX accelerator (pictured) with a facility known as Sirius.Credit: Carl de Souza/AFP via Getty

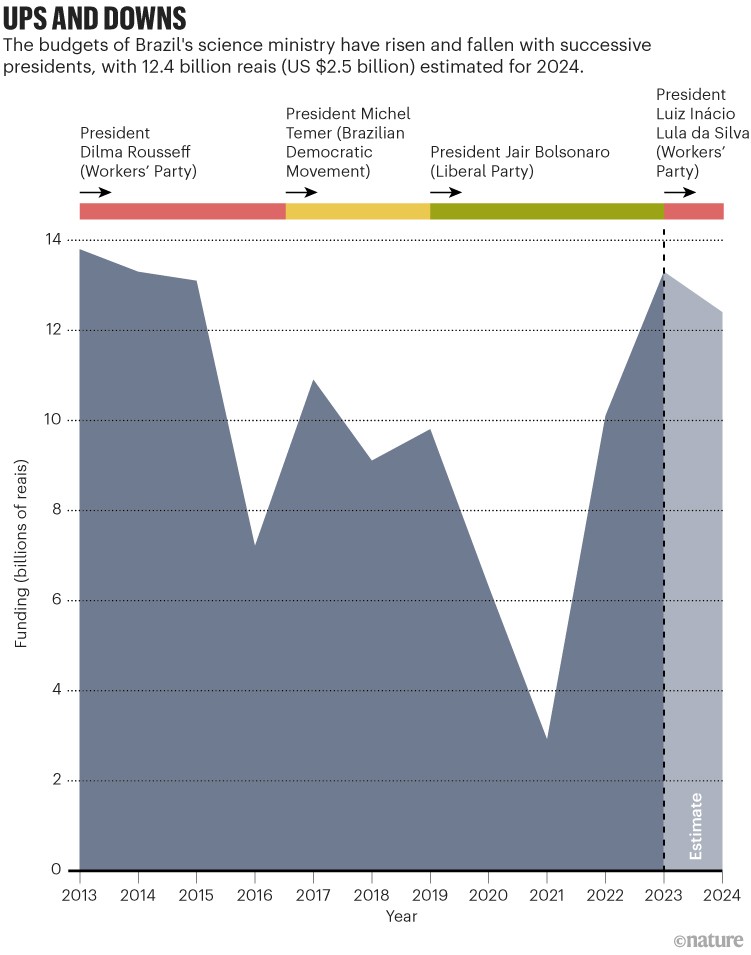

Gonçalves predicts that the government will find it hard to meet academics’ expectations. “Destruction is much more efficient and faster than construction,” he says. Renato Janine Ribeiro, president of the Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science (SBPC), who is based in São Paulo, says that areas such as science, health, education and the environment became even more vulnerable during Bolsonaro’s presidency than they were during the term of his predecessor, Michel Temer. In 2017, a group of 23 Nobel laureates sent Temer a letter expressing concern about the cuts in the funds for science and technology: the budget that year ended up being 44% lower than was originally approved by Congress, with a further cut predicted in 2018 in an attempt to reduce overall public expenditure (see ‘Ups and downs’).

Source: MSTI

Positive prospects

Many science-policy experts acknowledge that higher-education and science funding will never be adequate. “State funds will always be insufficient, but when government and civil society are aligned in their values and shared perception of reality, negotiation is possible. It was really hard to negotiate with an anti-science and anti-education government,” says Ribeiro.

The executive-secretary of Brazil’s science ministry, Luis Fernandes, counts three actions under Lula’s government that should inspire confidence. “The first and most important was the unlocking of resources from the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development (FNDCT) in their entirety.” At the end of August 2022, Bolsonaro edited a provisory act to limit the use of the fund — which also wasn’t fully used in previous years.

Managed by the science ministry, the FNDCT is fed by taxes collected from industrial sectors, such as those of biotechnology and energy, and is exclusively aimed at funding science and technology projects in Brazil. About 12 billion reais from the fund is available for use in 2024. Half of this will be invested in refundable operations (in which industrial or research institutions reimburse the fund) and the other half will go to straightforward investment in science and technology. The academic community is pushing to increase the non-refundable portion.

The second action, according to Fernandes, is the increase in the value of grants in the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), a science-ministry agency that focuses on funding projects in science and technology and supporting researchers at all levels of academia.

The CNPq is the main salary source for many Brazilian researchers, as well as the education ministry’s Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (known as CAPES) grants. As with the CNPq, CAPES, too, saw a rise in grant values in February 2023.

The third action is an effort to fill positions in public research institutions that had often been left empty when researchers retired and were not replaced. “We opened a public tender with over 800 positions. The lack of personnel was killing our research units by starvation,” Fernandes says.

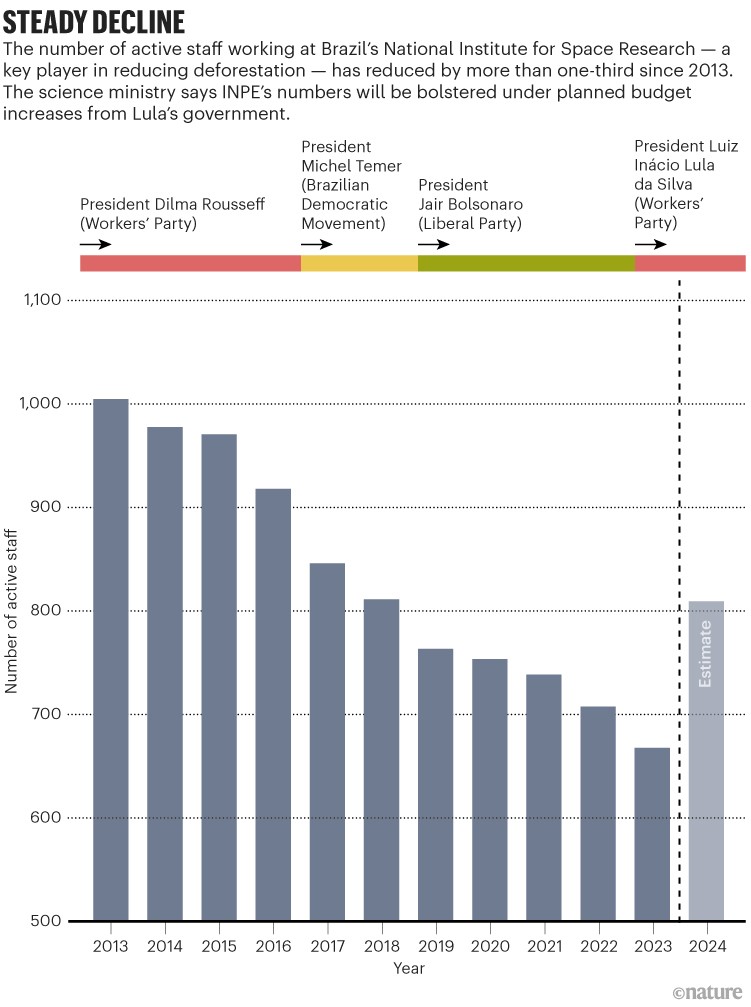

For example, the last time INPE had more recruits than departures was in 2014, when it hired 68 people. Since then, it has lost almost one-quarter of its workforce, shrinking from 978 in 2014 to 707 in 2022 (see ‘Steady decline’). Today, the institute has 667 civil servants — but the number is expected to increase because 142 of the 800 positions opened up in public research institutions are for INPE.

Source: INPE

After a difficult period following Galvão’s dismissal, INPE is slowly getting its house in order, says Leonel Perondi, a senior researcher in engineering and space technology at the institute. Carlos Nobre, president of the Brazilian Panel for Climate Change and a former INPE researcher, says, “Although the institute’s deforestation monitoring systems regained importance this year, it is still in dire straits,” pointing to areas such as weather forecast and climate modelling, which are still not as cutting-edge as they once were, mostly owing to the lack of a powerful supercomputer.

Higher-education secretary Denise Carvalho says that the top priority in 2023 was to give vulnerable students the right conditions to stay at university in a country where around one-third of the population live in poverty (living on less than US$6.85 a day). “Even before the pandemic, there were fewer enrolments and higher drop-out rates in courses across the country. This is worrisome because higher education is the most important component for social mobility in Brazil,” she says. According to the Institute of Applied Economic Research — a public research institution in Brazil’s Ministry of Economy — workers with a higher education earn on average four times more than do those who completed secondary school and did not go to university.

Future plans and current challenges

A key priority of Lula’s government, alongside restoring confidence in science and higher education, is an urgent need to shore up funding for advanced infrastructure projects, including a multipurpose reactor to provide radioisotopes for health research across the country, says Fernandes. Orion, Latin America’s first maximum-biosecurity laboratory, is also in the works. It will be connected to a source of synchrotron light at the Brazilian Center for Research in Energy and Materials in Campinas, less than 100 kilometres from São Paulo. The FNDCT will invest one billion reais in the project over the next couple of years. An expansion to the Sirius laboratory, at the same campus, is also in the plans. With 800 million reais invested over the same period, the idea is to add another 10 research stations to Sirius’ current 14 — of which 10 are functional.

CBERS-6, a satellite being developed by INPE and the China Academy of Space Technology in Beijing, is another project in the works. “The novelty is that it will embed in its monitoring capacity not only optical monitoring but radar detection — which will enable a much more precise surveillance of deforestation in the Amazon,” says Fernandes.

Tackling Brazil’s long-lasting brain drain will be essential to power these and other projects, Fernandes says. A programme known as Knowledge Brazil, scheduled to start at the end of this year, promises to create grants for researchers who want to return to Brazil, alongside subsidies to help Brazilian companies hire returning researchers. “We also want to create collaborative networks with Brazilian researchers abroad and treat them as national assets,” Fernandes adds. The challenge is working out precise numbers on how many Brazilian researchers are abroad.

There are no political guarantees that budgets will continue to recover from the years of turmoil. In mid-October, the Lula administration blocked 116 million reais from the 2023 CAPES budget. The amount is part of the 3.8 billion reais slashed from the government’s 2023 budget as an attempt to keep public expenditure within the limits set for 2023.

“We have to constantly strive to make things work,” says Ribeiro. He says that as well as having limited resources, support for science in Congress is not as strong as the scientific community would like, despite having advocates at the right and left of the political spectrum. “Science and technology don’t yield votes, so it is a hard fight — we have allies in the Congress, but they’re not the majority.”

“I’d say we’re living in times of careful hope,” says Gonçalves. “I believe things are going to get better, but we have to curb expectations because there are lots of interests at play that can make it difficult for the scenario to improve,” he adds. “We will feel the ripple effects of the last government for a long time.”

Politics and the environment collide in Brazil: Lula’s first year back in office

Politics and the environment collide in Brazil: Lula’s first year back in office

What a new president in Brazil could mean for science

What a new president in Brazil could mean for science