According to one study, reviewers in total do tens of millions of hours of peer review each year.Credit: Getty

Research papers are the product of lengthy discussions between authors and reviewers — guided by editors. These peer-review conversations can last for months at a time and are essential to progress in research. There is widespread agreement that the robustness and clarity of papers are enhanced in this process.

Peer-review exchanges are mostly kept confidential, meaning that the wider research community and the world have few opportunities to learn what is said in them. Such opacity can fuel perceptions of secrecy in publishing — and leaves reviewers and their key role in science publication underappreciated. It also robs early-career researchers of the opportunity to engage with examples of the inner workings of a process that is key to their career development.

In an attempt to change things, Nature Communications has since 2016 been encouraging authors to publish peer-review exchanges. In February 2020, and to the widespread approval of Twitter’s science community, Nature announced that it would offer a similar opportunity. Authors of new manuscript submissions can now have anonymous referee reports — and their own responses to these reports — published at the same time as their manuscript. Those who agree to act as reviewers know that both anonymous reports and anonymized exchanges with authors might be published. Referees can also choose to be named, should they desire.

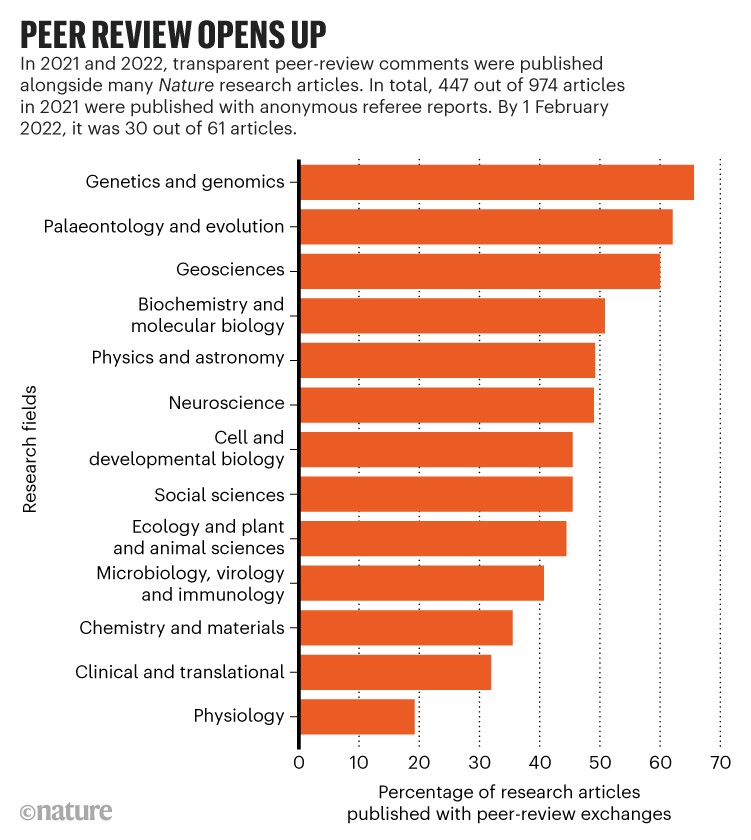

A full year’s data are now in, and the results are encouraging. During 2021, nearly half (46%) of authors chose to publish their discussions with reviewers, although there is variation between disciplines (see ‘Peer review opens up’). Early data suggest more will do so in 2022. This is a promising trend. And we strongly encourage more researchers to take this opportunity to publish their exchanges. Last year, some 69% of Nature Communication’s published research articles were accompanied by anonymous peer-review reports together with author–reviewer exchanges, including manuscripts in life sciences (73% of published papers), chemistry (59%), physics (64%) and Earth sciences (77%).

Source: Springer Nature

The benefits to research are huge. Opening up peer review promotes more transparency, and is valuable to researchers who study peer-review systems. It is also valuable to early-career researchers more broadly. Each set of reports is a real-life example, a guide to how to provide authors with constructive feedback in a collegial manner.

Publishing peer-review exchanges, in addition, recognizes the effort that goes into the endeavour. Peer review is integral to being a researcher. Making reviewers’ work public illustrates the lengths that researchers will go in the service of scholarship. According to one study, reviewers in total do tens of millions of hours of peer review each year (B. Aczel et al. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 6, 14; 2021). Yet this contribution is rarely recognized in research evaluation systems. As we have reported, there is growing interest in reforming these systems to better represent how science is done. If more researchers agree to open up their peer-review exchanges, we can all play a part in making that happen.

Nature will publish peer review reports as a trial

Nature will publish peer review reports as a trial

Research evaluation needs to change with the times

Research evaluation needs to change with the times

Why early-career researchers should step up to the peer-review plate

Why early-career researchers should step up to the peer-review plate

Three-year trial shows support for recognizing peer reviewers

Three-year trial shows support for recognizing peer reviewers

Let’s make peer review scientific

Let’s make peer review scientific